PLANET OF PERIL (23)

By:

December 4, 2017

One in a series of posts, about forgotten fads and figures, by historian and HILOBROW friend Lynn Peril.

“My boss is a rather flirty man,” began a letter to the Racine, Wisconsin, Journal Times Bulletin’s public opinion column in 1935. “There isn’t a day that goes by that he doesn’t come to my desk… puts his arm around me, and wants to start a necking party,” the writer continued, if a bit ungrammatically. But what came next was clear as a bell: “If I didn’t need work so badly, I’d slap his face, and that would mean my immediate dismissal. Then I would have to go without my only references…. I dislike this man very much, but how am I to make a living if I don’t work?”

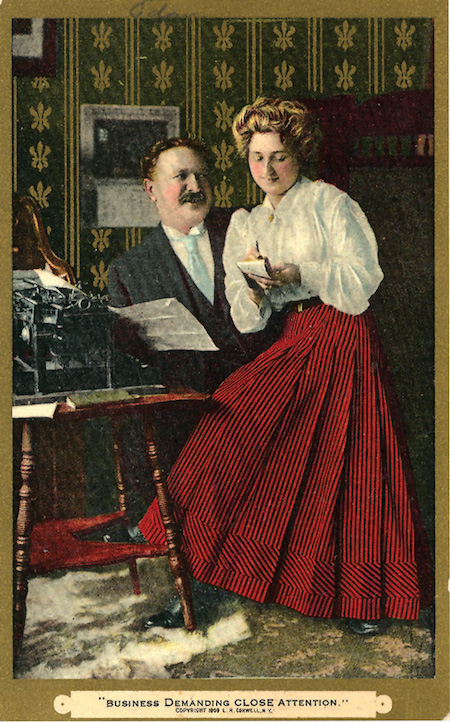

By the time D.M. unburdened herself to the Journal Times Bulletin (all letters were signed with initials only), American women had been working in offices for roughly three-quarters of a century. Assumptions about their sexual availability to higher-ups had been there from the start. Only a few years after Treasury Secretary Elias Spinner hired the first female clerks to replace male workers fighting the Civil War, the author of a salacious guide to Washington listed “treasury courtesans” among The Sights and Secrets of the National Capital (1869).

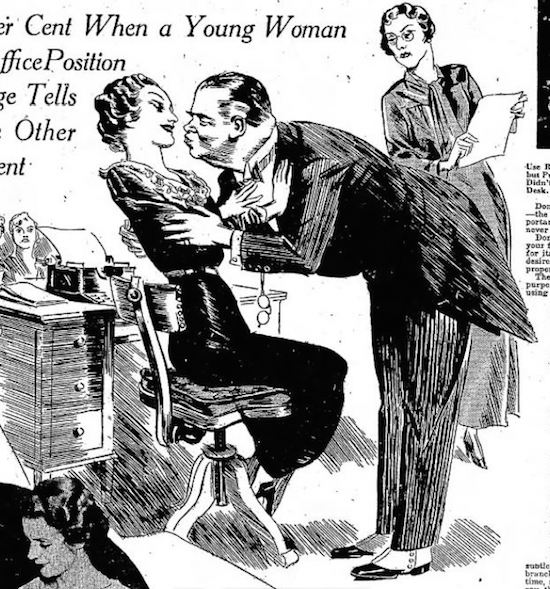

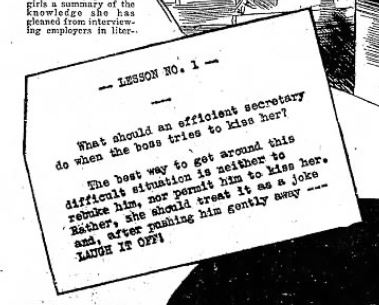

Long before the phrase “sexual harassment” was coined by a group of activists in 1975, most of the advice given to the victims of “flirty” bosses with busy hands was to avoid and ignore such behavior. Frequently, this was served up with the insinuation that the woman worker somehow “asked for it.” Columnist Laura Jean Libbey counseled “[m]odesty and maidenly reserve” as the “only safeguards for [the] protection” of the “young working girls” who wrote to her column shortly after the turn of the twentieth century.

The female author of The Ambitious Woman in Business (1916) suggested that the “average woman of intelligence” was “quite capable of freezing an undesired admirer into a state of respectful good sense, without even losing her job in the process.” But if the cold shoulder didn’t work, there was always the door. If it was “a case where she can not get rid of the attentions, she can, as a last resort get rid of the job…. She need never be kissed twice against her will.”

Elizabeth Gregg MacGibbon was a successful advertising woman who switched careers to become the author of Manners in Business (1936). A secretary (sounding much like D.M.) wrote to MacGibbon regarding the company president who had the habit “when passing a girl’s desk, of sometimes putting his hand under her chin in a playful manner, or patting her on the back of the neck. Apparently nothing very personal is meant by these gestures, but they don’t make us feel any too comfortable. How should we take it?” But what did the words “nothing personal” even mean when someone had their hands on your body without your permission — especially when that person was your boss and saying no might mean losing your job?

“Men who take advantage of their position to be indiscriminately familiar are beneath contempt,” wrote MacGibbon, showing an all-too-rare glimpse of anger at the perpetrator. “I should have liked to tell this light-fingered man that the rule in business is ‘Hands off.’” Alas, she didn’t. Instead, she counseled the secretary to make every effort to “be dignified under such circumstances,” no matter how difficult and thus, “by ignoring his actions, show him that she did not like such intimacies.”

One group of secretaries in MacGibbon’s account referred to the “light-fingered man” in their midst as “Felix the Feeler.” Thirty years later, the female author of The Secretary’s Guide to Dealing with People (1964) warned against another such feeler. He was “the crude one, usually the boss in a small office where there is no one to chide him for his activities. He is the pincher, the fanny-slapper, the squeezer, the nudger, the brusher-againster. The only thing to do about him,” she counseled, was “either develop quick reflexes for dodging and ducking, or slap his face and quit.”

Helen Gurley Brown, who, despite their similar backgrounds, considered MacGibbon an old fuddy-duddy when it came to office etiquette, suggested that groping was a price an experienced secretary might be willing to pay for employment. “A wolfish interviewer isn’t necessarily a reason to bolt,” she wrote in Sex and the Office (1964), a guide to sleeping with one’s coworkers. “Nancy told me of an initial chat with a tire tycoon who very smoothly caught her in a hammerlock and pressed his mouth to hers as she was getting up from her chair. She was broke and decided to take the job anyway. Her instincts said this lunatic acted that way with all girls and probably never followed through. She was right.” Brown made a distinction between young, inexperienced women who didn’t have “enough experience in separating the cobras from the garter snakes” and “grownups” who knew the distinction between someone legitimately “wolfy” and someone “acting the way men act in offices” (the italics were hers).

Brown was an outlier, of course. The majority of women office workers were there for a paycheck, not romance, and the advice to dodge, ignore or laugh off an improper glance, touch, or word wasn’t very helpful in real life. “I’ve always believed a girl got what she asked for but right now that doesn’t help much,” wrote the married recipient of too much attention, including phone calls at home, from one of her male coworkers, to Los Angeles Times advice columnist Amy Abbot in 1958. “I know of nothing wrong in my behavior. I dress, smile and talk as well as I can because I want to be liked, but see no reason why it should be taken as a come-on.” Abbott assured the woman that if she kept on “being pleasant, courteous and unavailable,” she’d “eventually discourage” her harasser.

Abbott’s final words made it clear where she suspected responsibility for the whole ugly episode lay: “That is what you want, isn’t it?”

PLANET OF PERIL: THE SHIFTERS | THE CONTROL OF CANDY JONES | VINCE TAYLOR | THE SECRET VICE | LADY HOOCH HUNTER | LINCOLN ASSASSINATION BUFFS | I’M YOUR VENUS | THE DARK MARE | SPALINGRAD | UNESCORTED WOMEN | OFFICE PARTY | I CAN TEACH YOU TO DANCE | WEARING THE PANTS | LIBERATION CAN BE TOUGH ON A WOMAN | MALT TONICS | OPERATION HIDEAWAY | TELEPHONE BARS | BEAUTY A DUTY | THE FIRST THRIFT SHOP | MEN IN APRONS | VERY PERSONALLY YOURS | FEMININE FOREVER | “MY BOSS IS A RATHER FLIRTY MAN” | IN LIKE FLYNN | ARM HAIR SHAME | THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE FLAPPER | THE GHOST WEEPS | OLD MAID | LADIES WHO’LL LUSH | PAMPERED DOGS OF PARIS | MIDOL vs. MARTYRDOM | GOOD MANNERS ARE FOR SISSIES | I MUST DECREASE MY BUST | WIPE OUT | ON THE SIDELINES | THE JAZZ MANIAC | THE GREAT HAIRCUT CRISIS | DOMESTIC HANDS | SPORTS WATCHING 101 | SPACE SECRETARY | THE CAVE MAN LOVER | THE GUIDE ESCORT SERVICE | WHO’S GUILTY? | PEACHES AND DADDY | STAG SHOPPING.

MORE LYNN PERIL at HILOBROW: PLANET OF PERIL series | #SQUADGOALS: The Daly Sisters | KLUTE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: BLOW-UP | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA series | HERMENAUTIC TAROT: The Waiting Man | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Young Romance | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife | HILO HERO ITEMS on: Tura Satana, Paul Simonon, Vivienne Westwood, Lucy Stone, Lydia Lunch, Gloria Steinem, Gene Vincent, among many others.