PLANET OF PERIL (19)

By:

August 10, 2017

One in a series of posts, about forgotten fads and figures, by historian and HILOBROW friend Lynn Peril.

Sometimes in dreams I find myself in an enormous thrift store, filled with all the dusty old things I like best. I grab Starburst plates and Schiaparelli scarves, teenage dating guides, and black-and-white go-go boots. The line at the checkout is abnormally long and even slower moving than in real life, which is quite a feat because time frequently stands still when some kind of crazy drama plays out ahead of you when shopping on your lunch hour. (Trust me here. I once kept my place in line when an argument between customers inside the store erupted into a knife fight outside.) Whether or not I’ve made a purchase by dream’s end, I wake up empty handed and sad that that neither loot nor store exists.

Imagine then, how I felt reading about the merchandise available at the League of Women Voters’ Manhattan thrift shop in 1923. “We had two big boxes of fancy underwear come in yesterday, and it’s all gone now,” the woman behind the counter told a visiting reporter from the New York Times. “We have had some wonderful women’s hats which we sell from $4 down. Some of them had not been worn at all.” Women’s handbags went “like hot cakes.” There was even “a signed photograph of Emmeline Pankhurst, the suffragist leader.” I drooled at the thought.

The same article noted that the League of Women Voters was the fourth thrift shop in New York City. The fourth? What was the first? What was the origin of my dearly beloved thrifting?

Preliminary investigations make a note on nomenclature necessary. During the early part of the twentieth century, the phrase “thrift store” might mean either a discount store or a “bargain basement” location within a regular store where they sold returns, irregulars, display models, and the like. (This usage hangs on; late-twentieth century thrifters will recall the sinking feeling when the out-of-the-way thrift store they tracked down on vacation turned out to sell day-old bakery.) A “thrift shop” was a store that sold secondhand goods for the benefit of a charity. But before either thrift shop or store, there was the rummage sale.

To rummage a ship, according to The Century Dictionary (1890), was to “arrange or stow the cargo… in its hold.” A rummage sale was thus “a clearing-out sale of unclaimed goods at docks, or of miscellaneous articles left in a warehouse.” In practice, this could mean absolutely anything under the sun, from bales of wire to crates of wine to the 200 pounds of oleomargarine, abandoned for three years, that nevertheless sold for fifty cents at a Philadelphia rummage sale in 1896. “The auctioneer held his breath while awaiting bids and some of the office force nearly fainted on account of the odor.” The successful bidder said he was going to use the vile stuff in place of axle grease.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, charitable organizations began to use rummage sales as a way of taking in cash. Rummage sales on the docks were men’s space, but these new sales were run almost exclusively by upper- or middle-class women. Somewhere along the line, the unsavoriness that could accrue to secondhand goods (fears of contagion or infestation, association with unscrupulous pawnbrokers, the fear of being thought poor) was overcome by the pleasure of finding bargains in the guise of assisting the needy.

A certain giddiness pervaded much of the initial coverage of the charity rummage sale, as if people couldn’t quite believe they could make money selling household junk. A short story, “The Rummage Sale,” that appeared in an English magazine in 1893 also suggested that the transformation from dockside auction to ladies’ fundraiser was an idea that came from across the Atlantic.

“But what sort of things [are sold at a rummage sale], my dear, and how do you get them? Is it a bazaar?” asked Lady Jane, of Miss Hately’s “American Fair.”

“No, no; absolute rubbish sells best. Teapots with no spouts, legs without tables, I mean tables and chairs without legs or arms, old boots, old hats — anything.”

“And you made twenty pounds?”

“Easily, dear Lady Jane, easily. We could have made forty, but we had nothing left, except a broken typewriting machine and some champagne bottles.”

This last little dig may be familiar to individuals whose garage sales never seem to live up to the money-making potential of those bragged about by friends and neighbors. Then again, who among us has had a sale like Lady Jane’s, where twin sisters, separated when one runs off with a man who proves to be a bigamist, meet again when the poor one unknowingly buys the rich one’s cast-off dress?

A sense of wonderment at the sheer diversity of articles for sale pervades stateside coverage of what was a still-new phenomenon around the turn of the twentieth century. “The ‘rummage’ sale, while not an auction or a bargain counter, comprises the best features of both attractions,” explained the New-York Tribune in 1900. “There is absolutely no limit to the variety of goods offered. Everything imaginable is displayed, from white wedding dresses to lawn mowers and pickaxes.” A visitor to a San Francisco rummage sale in 1902 saw “hats, coats, frocks, waists, shoes, crockery, furniture, jewelry, and every other article useful in the household… classified, cleaned, patched, mended, and tagged with price.”

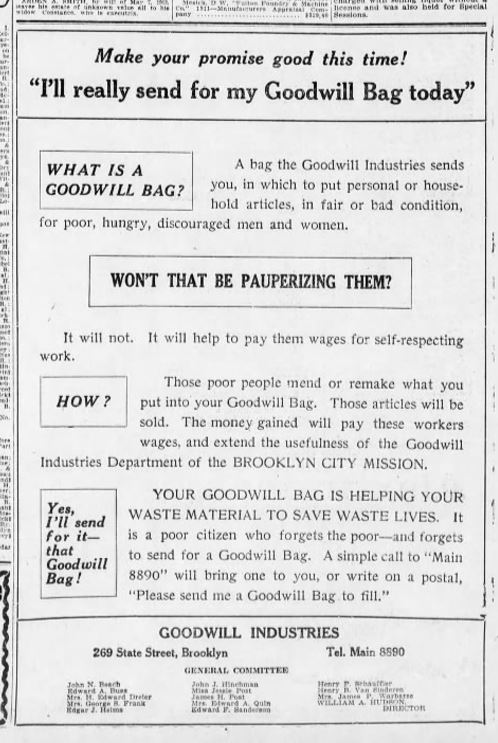

The idea of fixing up donated goods before selling them was one of the underlying tenets of Goodwill Industries, which opened its doors in Brooklyn in 1915. Goodwill requested donations of articles “in fair or bad condition” using special canvas “Goodwill Bags” made by the organization’s clients: “poor, hungry, discouraged men and women.” Goodwill operated with an up-by-their-bootstraps attitude. “WON’T THAT BE PAUPERIZING THEM?” asked an early, explanatory ad asking for donations. There was to be no endless suckling at charity’s teat, because Goodwill had “those poor people mend or remake” the donated items, thus earning “wages for self-respecting work.” This was a popular model for organizations working with the poor around the time of the First World War. The Mending and Thrift Shop in Chicago “distributed old clothing to the needy of the ward, although the purpose of the mending shop is far removed from any thought of charity. It is to train women as earners not receivers.” A “carefully and honestly conducted” salvage bureau (as the St. Vincent de Paul Society called their version) did “far more good than indiscriminate giving, which tends to encourage shiftlessness and graft,” concluded the newspaper in Elmira, New York, of its County Thrift Shop in 1919.

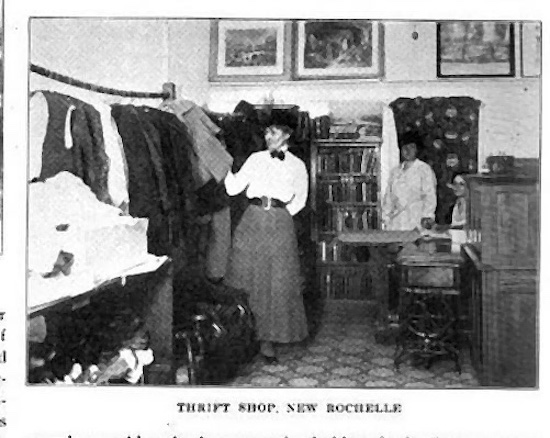

“Thrift shops have been called ‘glorified rummage sales,’” noted a 1920 article on the Women’s Auxiliary of the Infant Welfare Society of Chicago’s latest fundraising venture. Charity thrift shops sprang up all over the place in the 1920s, and they sound very modern indeed, as does their clientele. Shopping at these stores became a good act in and of itself. “Every sale, it must be remembered, goes to help some little child to retain health and happiness,” concluded a 1920 ad for The Thrift Shop of the Orthopedic Hospital in Seattle, forestalling any dull arguments about want versus need. The Jack Horner Thrift Shop (opened in 1921 to the benefit of five charities, it was likely the first in New York City) put it in rhyme: “Help Little Jack Horner take things from your corner / To put in our Thrift Shop Pie / Needy folk with a thumb will pull out a plum / Then you’ll say, ‘What a good deed did I.’”

Unlike the salvage bureaus with their resoled shoes and madeover dresses, these thrift shops made no bones about the quality of their goods and readily sought bargain seekers from all socioeconomic strata. “Men Are Buyers as Well as Women” was a subheadline on the Times article about the League of Women Voters’ shop, a far cry from those manly dockside rummage sales. Also mentioned was the shop’s “limousine trade” of well-to-do customers, as well as the presence of “two Negro women” shoppers, one who bought a silk skirt and the other a children’s book. There were even “some customers who come in every single day.” I recognize the type.

PLANET OF PERIL: THE SHIFTERS | THE CONTROL OF CANDY JONES | VINCE TAYLOR | THE SECRET VICE | LADY HOOCH HUNTER | LINCOLN ASSASSINATION BUFFS | I’M YOUR VENUS | THE DARK MARE | SPALINGRAD | UNESCORTED WOMEN | OFFICE PARTY | I CAN TEACH YOU TO DANCE | WEARING THE PANTS | LIBERATION CAN BE TOUGH ON A WOMAN | MALT TONICS | OPERATION HIDEAWAY | TELEPHONE BARS | BEAUTY A DUTY | THE FIRST THRIFT SHOP | MEN IN APRONS | VERY PERSONALLY YOURS | FEMININE FOREVER | “MY BOSS IS A RATHER FLIRTY MAN” | IN LIKE FLYNN | ARM HAIR SHAME | THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE FLAPPER | THE GHOST WEEPS | OLD MAID | LADIES WHO’LL LUSH | PAMPERED DOGS OF PARIS | MIDOL vs. MARTYRDOM | GOOD MANNERS ARE FOR SISSIES | I MUST DECREASE MY BUST | WIPE OUT | ON THE SIDELINES | THE JAZZ MANIAC | THE GREAT HAIRCUT CRISIS | DOMESTIC HANDS | SPORTS WATCHING 101 | SPACE SECRETARY | THE CAVE MAN LOVER | THE GUIDE ESCORT SERVICE | WHO’S GUILTY? | PEACHES AND DADDY | STAG SHOPPING.

MORE LYNN PERIL at HILOBROW: PLANET OF PERIL series | #SQUADGOALS: The Daly Sisters | KLUTE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: BLOW-UP | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA series | HERMENAUTIC TAROT: The Waiting Man | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Young Romance | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife | HILO HERO ITEMS on: Tura Satana, Paul Simonon, Vivienne Westwood, Lucy Stone, Lydia Lunch, Gloria Steinem, Gene Vincent, among many others.