PLANET OF PERIL (18)

By:

July 8, 2017

One in a series of posts, about forgotten fads and figures, by historian and HILOBROW friend Lynn Peril.

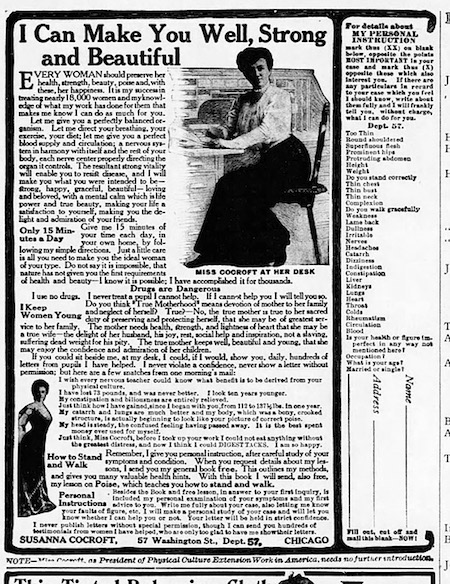

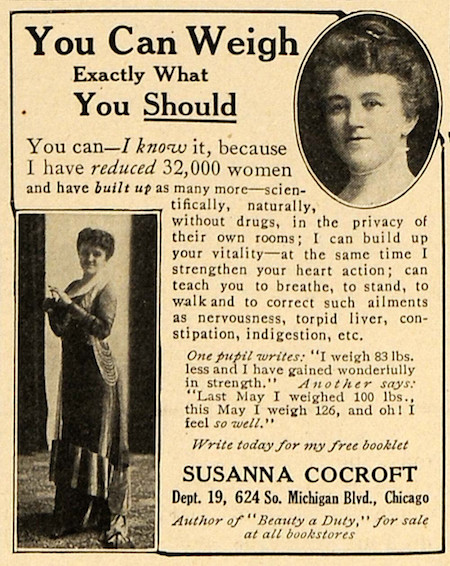

Decades before novelist Patrick Dennis put similar words in his fictitious Auntie Mame’s mouth, early-twentieth-century health and beauty guru Susanna Cocroft exhorted women to “LIVE!” All but forgotten now, it was once almost impossible to pick up a newspaper or a woman’s magazine, from stalwart Good Housekeeping to rarified Vogue, without coming across an ad for Cocroft’s mail-order course. Need to lose a few pounds? Cocroft could help. Too skinny? Cocroft could help with that too. Was your liver torpid or did you suffer from “mal-assimilation”? You came to the right place. A pleasant-looking middle-aged woman whose photo appeared in almost every ad, Cocroft promised all things to all people, in just 15 minutes a day.

Born in 1862, the 31-year-old Cocroft left her job as a small-town Wisconsin school administrator and teacher for a position editing a “humorous” magazine, American Tit-bits, in Chicago. This was a bold occupation for a female in 1893, unusual enough that a newspaper in Louisville ran a brief item about Cocroft and her belief that “a woman could be successful as a man” when it came to publishing. In a portent of things to come, “Susie” Cocroft’s picture appeared next to the article.

The author of nearly a dozen books and pamphlets, Cocroft rarely engaged in autobiography (self-aggrandizement was another matter entirely). Exactly when and where she became acquainted with the health and strength training movement remains murky, but by 1895, she was the secretary of Chicago’s Physical Culture Extension Society (she later billed herself as the organization’s “originator”). There, she developed a course of forty-eight lessons for women, including “how to promote and preserve beauty of face and form; to acquire ease, dignity, self-possession … how to walk, sit, stand,” all building blocks of her later mailorder course. Cocroft was “a very clever young woman,” opined The Saint Paul Globe, who seemed “destined to take a high place among the devotees of physical culture.”

This was prescient; by shortly after the turn of the century, Cocroft’s advertising was everywhere. Written in the first person, the copy played on women’s social fears and perceived defects in a way familiar to consumers of modern media. “Young at Forty” read a tantalizing headline of 1907. According to a 1920 ad, she had “helped 98,000 women to regain health and good figures. These women are most of the best American type—refined, intellectual.” The cagey Cocroft even bought advertising space in American Medicine and other journals, then noted that “Medical Magazines advertise my work” in the ladies’ mags. “Have a perfect figure! Be Happy! Enjoy life! Be a source of inspiration to your friends.” Who didn’t want all those things? And it all sounded so easy! “You can surprise your husband and friends by giving 15 minutes a day, in your room, to special directions which I give you to strengthen vital organs and nerves, so you are relieved of chronic ailments.” Later ads quietly dropped “Too short” and “Height” from the list of conditions Cocroft promised to correct.

Though Cocroft declared in Habits: Their Effect Upon Life (1911) that she had “been the means of changing the thought current and thus the entire life and purpose of thousands of women, who had been discouraged and unhappy,” not everyone came away from a Cocroft course happy and improved. Historian Kathy Peiss related the story of Ethel Vining, who paid $18.00 to take Cocroft’s course in 1913:

Cocroft asked Vining for a “kodak picture, showing the lines of your figure,” noting “I like to keep my pupil’s face before me as I dictate her lesson.” Every few weeks, Cocroft sent her a form letter — personalized with references to Vining’s case — with instructions for dieting and exercise and leaflets advertising her toilet preparations. Vining, in turn, dutifully sent in reports detailing her weight and measurements. “If you could realize how eagerly I scan your report,” said Cocroft, “I am watching your progress.” Three weeks later, however, the relationship had begun to turn sour. “There is something wrong with the way you are doing your work,” she complained. “You are not reducing as rapidly as you should, Mrs. Vining.”

Clearly, Mrs. Vining was a slacker. To Cocroft, beauty was a duty that every woman performed for the sake of those around her, a philosophy she laid out in the aptly named Beauty A Duty (1915). A woman who neglected “making the most of her personal gifts” was not only “burying her talents” but “failing to contribute to the beauty and to the uplift of the world.”

Moreover, physical beauty equaled power in Cocroft’s decidedly nonfeminist reckoning. She tallied the dividends paid to a beautiful woman:

- Crowds make way for her.

- Busy men stop to listen to her.

- Men of influence use their power to help her gain what she desires.

- She is first to be served at shop or table.

- She is the center of an admiring group at every social gathering.

- Women as well as men love and admire her.

- She is a leader, — the most influential kind of leader.

Why?

Because she is beautiful; and if you look closely, you will find that the culture of heart and mind and the refined nature, have led her to give careful attention to the details of her toilet.

Rather than question why any woman, regardless of appearance, needed a man’s agency instead of her own, Cocroft chose to sell the illusion of beauty, along with a toilet product or two.

Cocroft even added a dash of New Age-iness to the mix. She was an adherent of the New Thought Movement, a mash-up of philosophies and theosophies that owed not a little to Christian Science in that one of the central beliefs was that disease was the result of “false reasoning,” and could be cured with “healthy-mindedness.” Growth in Silence: The Undertone of Life (1918) was fairly bursting with metaphysical mumbo-jumbo:

With what a draft of pure exhilaration we open the eastern windows of the morning to the new day! The new day — its surface is unruffled! The yesterday has gone into the west— only the thoughts of that day which make for eternity have been traced upon its pages. The mantle of rest and of silence has tenderly covered it, while the night has borne it with silent tread, hours away! The soft night wind has lulled it to dreamless, lasting sleep.

A reviewer at the San Francisco Chronicle mocked Cocroft’s “rhapsodies” and noted “the stout ladies who have envied the author her silhouette will search in vain for definite rules for their guidance.” (The reviewer nevertheless predicted the book would “probably prove popular.”)

Cocroft’s influence perhaps reached a zenith in the summer of 1918 when, with the federal government’s support, she led 3500 women in “setting up exercises” and military drill on the Ellipse in a bid to “make Washington’s girl war workers healthy and happy.” Cocroft dreamed of a peacetime United States Training Corps for Women, whereby women office workers, teachers, and housewives would spend two weeks every summer in the great outdoors, building bodies, as well as hearts and minds. After the First World War ended, prototype camps opened at Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, and Asheville, North Carolina, but funding lagged and the Corps never fully came to fruition.

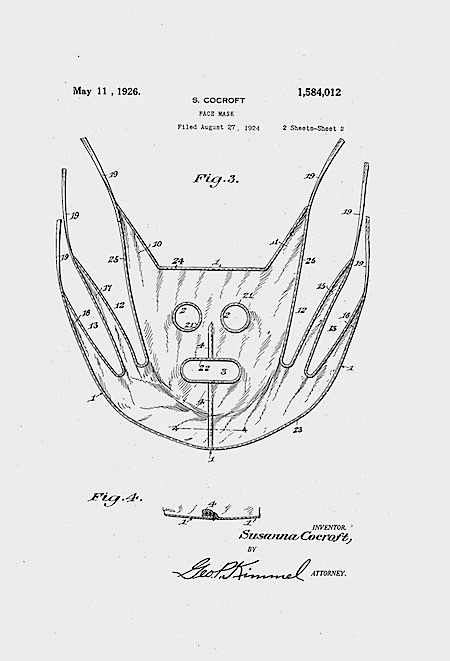

Perhaps it was the failure of the Corps, or the death of her husband in 1923, or simply age (she turned 58 in 1920), but the wind seems to have gone out of Cocroft’s sails in the new decade. She experimented with technology, and offered her course on records, with or without music (“Note how you are thrilled and inspired by the spirited music — how the charts and the clear voice from the record, giving crisp, decision ‘commands,’ make each exercise fascinating and enjoyable”). Her advertising focused less on her personalized course and more on items like a “Rejuvenating Silk Mask” that promised “New Beauty Overnight” or a device worn under the hair that pulled one’s jowls back to produce a facsimile of youth “as effective as a $2000.00 surgical operation.” Women’s Wear Daily noted in 1925 that Cocroft (who had long counseled followers not to “depend upon the corset to make a good figure”) had lent her name to a rubber girdle. Perhaps anticipating a modern world where busy women found 15 minutes a day too many, the garment was said to make “the figure appear thin as soon as it is worn.”

PLANET OF PERIL: THE SHIFTERS | THE CONTROL OF CANDY JONES | VINCE TAYLOR | THE SECRET VICE | LADY HOOCH HUNTER | LINCOLN ASSASSINATION BUFFS | I’M YOUR VENUS | THE DARK MARE | SPALINGRAD | UNESCORTED WOMEN | OFFICE PARTY | I CAN TEACH YOU TO DANCE | WEARING THE PANTS | LIBERATION CAN BE TOUGH ON A WOMAN | MALT TONICS | OPERATION HIDEAWAY | TELEPHONE BARS | BEAUTY A DUTY | THE FIRST THRIFT SHOP | MEN IN APRONS | VERY PERSONALLY YOURS | FEMININE FOREVER | “MY BOSS IS A RATHER FLIRTY MAN” | IN LIKE FLYNN | ARM HAIR SHAME | THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE FLAPPER | THE GHOST WEEPS | OLD MAID | LADIES WHO’LL LUSH | PAMPERED DOGS OF PARIS | MIDOL vs. MARTYRDOM | GOOD MANNERS ARE FOR SISSIES | I MUST DECREASE MY BUST | WIPE OUT | ON THE SIDELINES | THE JAZZ MANIAC | THE GREAT HAIRCUT CRISIS | DOMESTIC HANDS | SPORTS WATCHING 101 | SPACE SECRETARY | THE CAVE MAN LOVER | THE GUIDE ESCORT SERVICE | WHO’S GUILTY? | PEACHES AND DADDY | STAG SHOPPING.

MORE LYNN PERIL at HILOBROW: PLANET OF PERIL series | #SQUADGOALS: The Daly Sisters | KLUTE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: BLOW-UP | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA series | HERMENAUTIC TAROT: The Waiting Man | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Young Romance | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife | HILO HERO ITEMS on: Tura Satana, Paul Simonon, Vivienne Westwood, Lucy Stone, Lydia Lunch, Gloria Steinem, Gene Vincent, among many others.