INTO THE GROVE (18)

By:

June 29, 2017

One in a series of posts, by long-time HILOBROW friend and contributor Brian Berger, celebrating perhaps America’s most exciting and controversial publisher: Barney Rosset’s Grove Press.

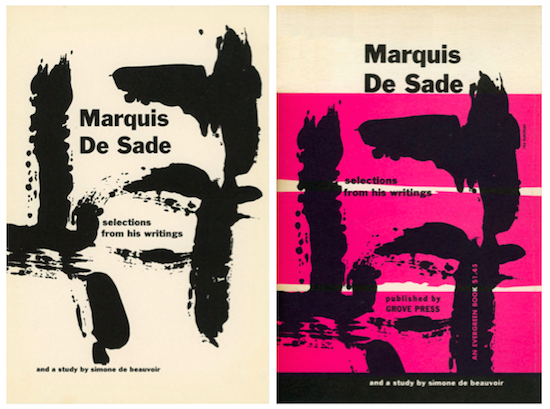

Marquis de Sade’s Selected Writings, with a study by Simone de Beauvoir, compiled and translated by Paul Dinnage (1954)

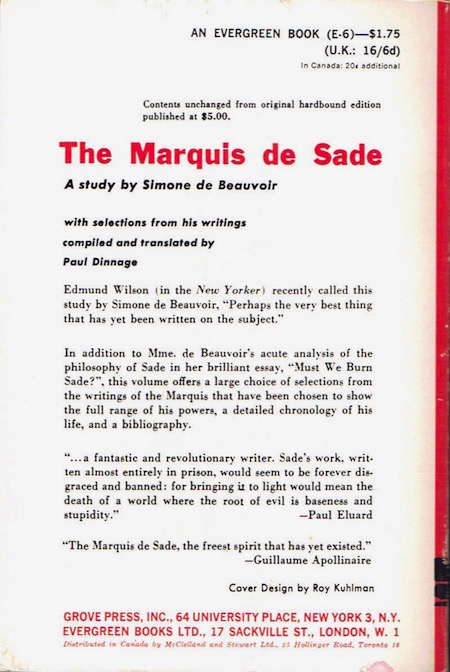

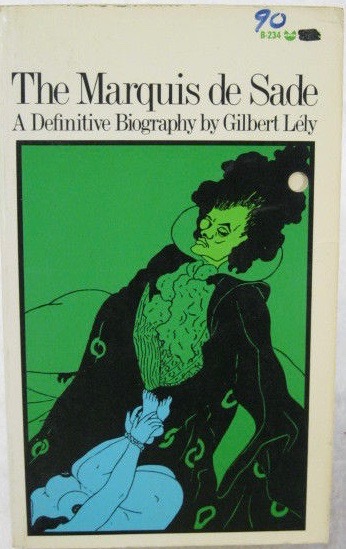

Gilbert Lély’s The Marquis de Sade: A Definitive Biography (hardcover 1962, paperback 1970), translated by Alec Brown

Marquis de Sade’s The Complete Justine, Philosophy in the Bedroom and other writings, compiled and translated by Richard Seaver & Austryn Wainhouse, with introductions by Jean Paulhon & Maurice Blanchot (1965)

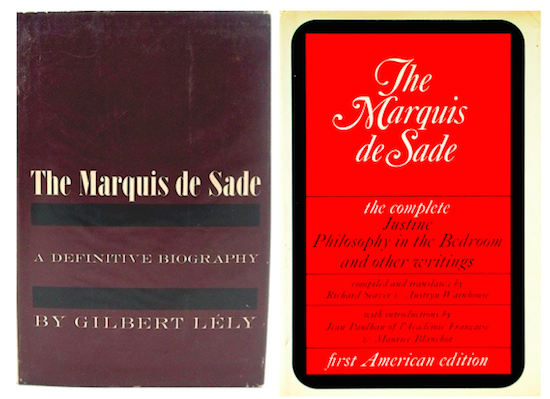

Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom and Other Writings, translated by Austryn Wainhouse & Richard Seaver, introductions by Simone de Beauvoir & Pierre Klossowski (1966)

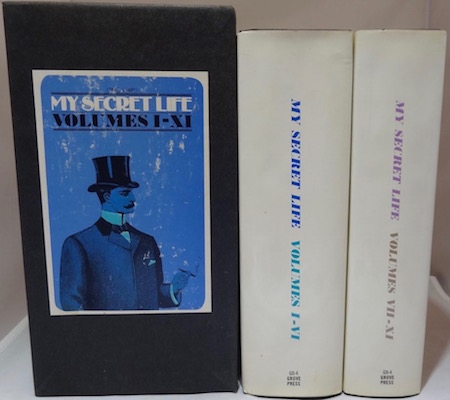

Anonymous’ My Secret Life, introduction by Gershon Legman (c. late 19th c., 1966)

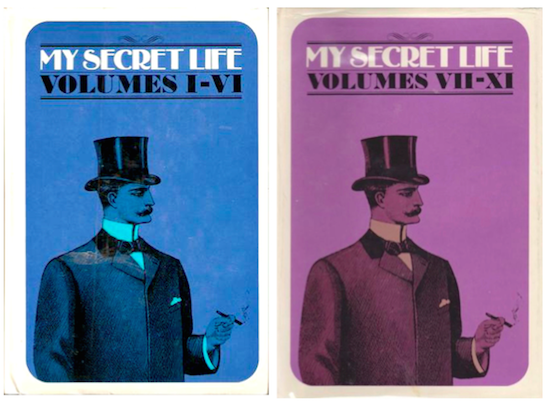

Anonymous’ Sadopaideia (1967)

Yukio Mishima’s Madame de Sade (1967)

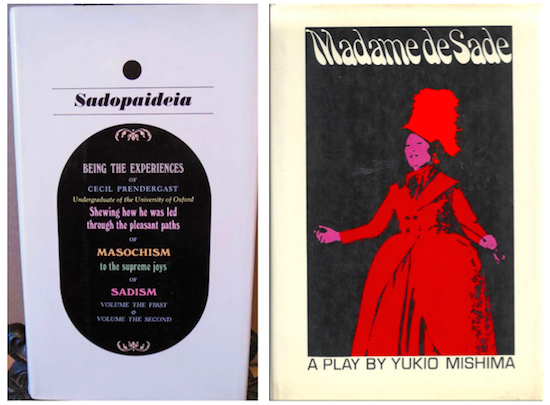

Anonymous’ Harriet Marwood, Governess (date unknown, 1967)

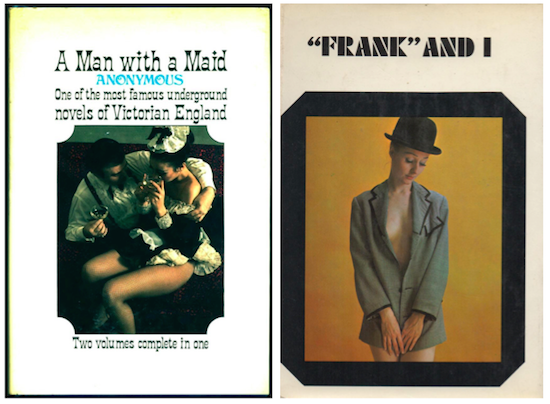

Anonymous’ A Man with a Maid (c. 1908, 1968)

Anonymous’ Frank and I (c. 1902, 1968)

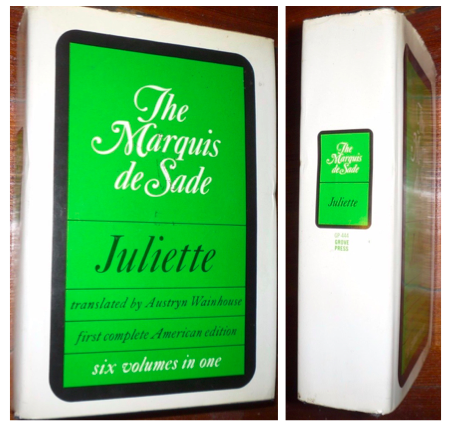

Marquis de Sade’s Juliette translated by Austryn Wainhouse (1968)

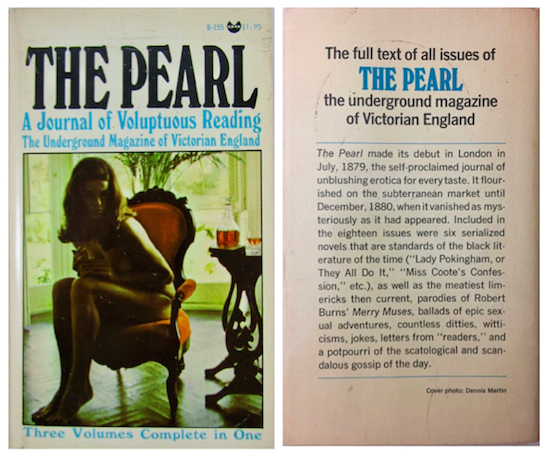

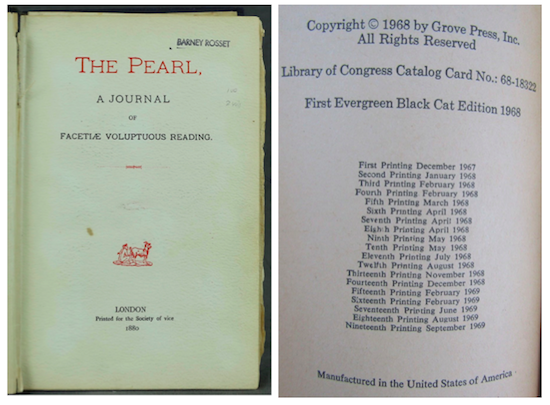

Anonymous’ The Pearl: A Journal of Voluptuous Reading, The Underground Magazine of Victorian England (1879-1880, 1968)

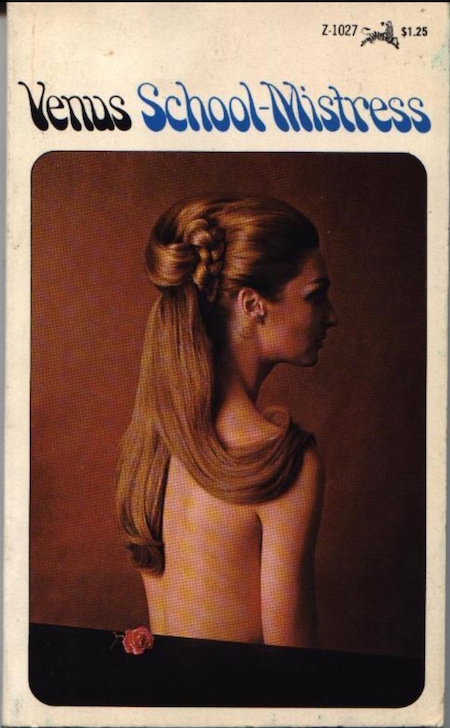

Anonymous’ Venus School-Mistress, or Birchen Sports (c. 1788, 1968)

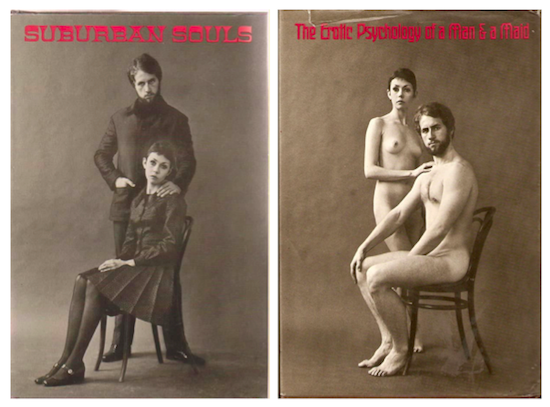

Anonymous’ Suburban Souls: The Erotic Psychology of a Man & a Maid (1901, 1968)

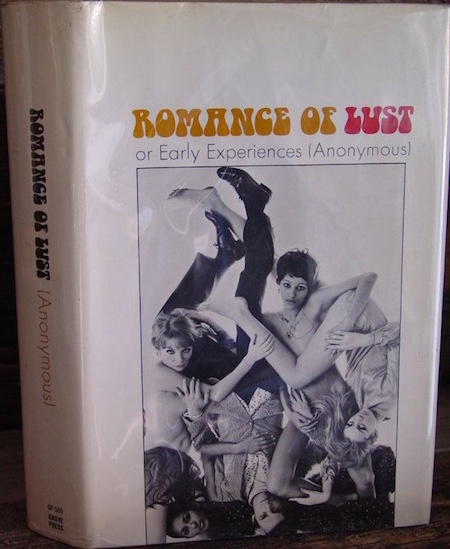

Anonymous’ Romance of Lust, or Early Experiences (1873-1876, 1968)

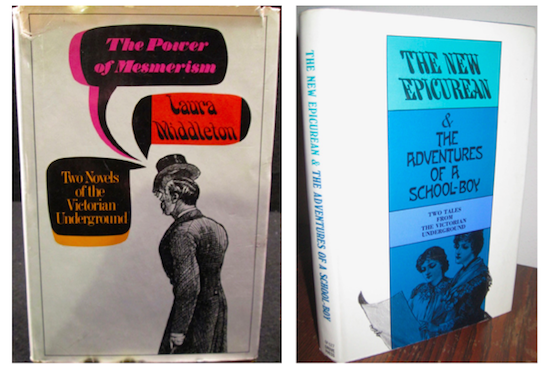

Anonymous’ The Power of Mesmerism & Laura Middleton: Two Novels from the Victorian Underground (c. 1891 & 1890, 1969)

Anonymous’ The New Epicurean & Adventures of a School-boy: Two Tales from the Victorian Underground (1865 & 1866, 1969)

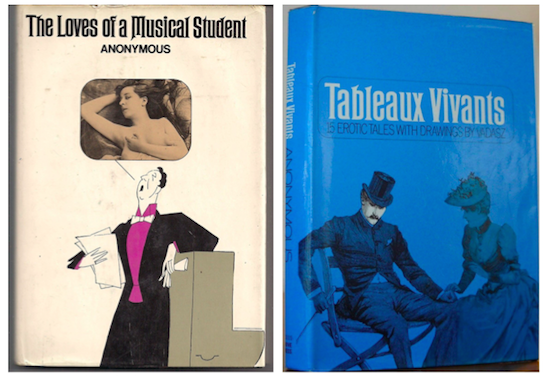

Anonymous’ The Loves of a Musical Student (c. 1860, 1969)

Anonymous’ Tableaux Vivants, Fifteen Erotic Tales (c. 19th century, 1969), translated by by a Member of Erotika Biblion Society, drawings by Nicolaus Vadasz

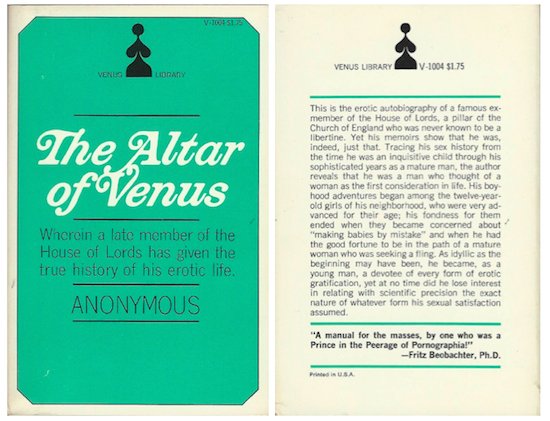

Anonymous’ The Altar of Venus (1934, 1969)

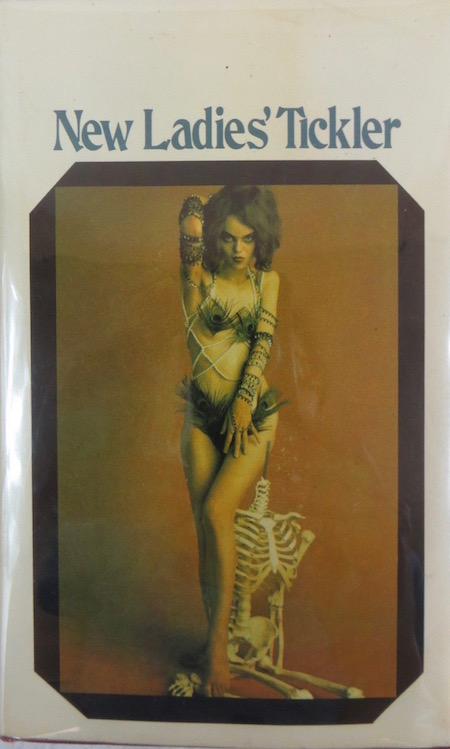

Anonymous’ The New Ladies Tickler, or the Adventures of Lady Lovesport and the Audacious Harry (c. 1860s, 1970)

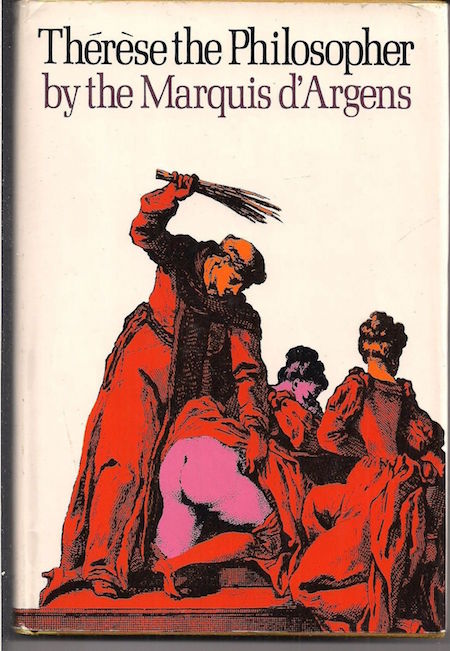

Marquis d’Argens’ Thérèse the Philosopher (1748, 1970)

Gilbert Lély’s The Marquis de Sade: A Definitive Biography (1962, 1970), translated by Alec Brown

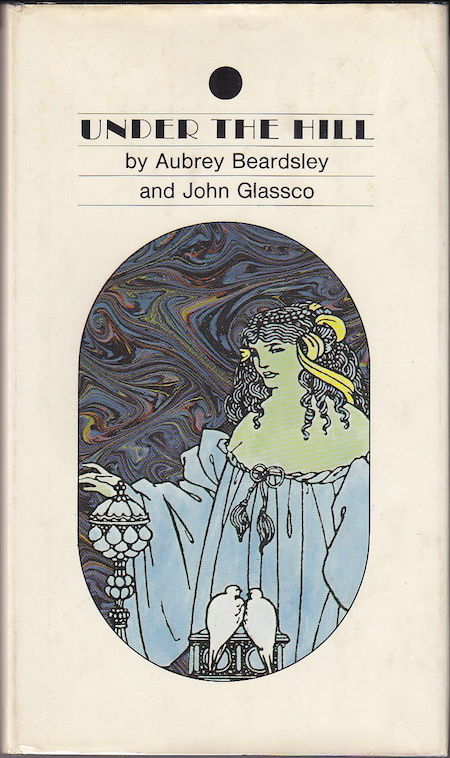

Aubrey Beardsley’s & John Glassco’s Under The Hill (1959, 1967)

All cover designs by Roy Kuhlman (exclusive of photographs)

All quotes from original jacket copy

***

And then came the Marquis de Sade. Though Barney Rosset had published Sade before: first in 1954, with a respectable but necessarily limited anthology, and again in 1962, with a little seen, hardcover only, biography, these were neither culture nor business shaking events. Following the liberations of D.H. Lawrence and Henry Miller, however, the age demanded more — even more than the likes of Genet, Burroughs and Selby allowed. So while Grove Press would continue to move forward, maintaining its role as a leading purveyor of contemporary avant- literatures and such, it would also plunge deep into the legacy dirty books past, particularly the shadow-world of high-spirited, taboo-less and often pansexual Victorian erotica, nearly all of which was in the public domain. While the appearance of any given title on this or that Grove imprint (including Evergreen, Black Cat, Black Circle, Venus and Zebra) can be as mysterious as a works’ original provenance, these offerings were generally in keeping with Grove’s established interests. There were some differences, however. Some of Roy Kuhlman’s cover designs are plainly subservient to dirty book marketing demands (though various photographers and their models were able to cut loose) and because this wasn’t Beckett for chrissakes, Grove wasn’t above… a little mischief, sometimes, and perhaps even a deadpan literary hoax.

***

“It is necessary to keep coming back to Sade, again and again.” — Baudelaire

“The Marquis de Sade, the freest spirit that has ever lived.” — Apollinaire

“Sade must be given a place in the great family of those who cut through the ‘banality of everyday life’ to a truth which is immanent in this world… Sade’s style, in its gaiety, its violence and its arrogant rawness proves to be that of a great writer.” — Simone de Beauvoir

“One of the most influential works of the last two hundred years… beautifully presented and translated.” — Professor Henri Peyre, Yale University on 120 Days of Sodom

“In two handsomely designed volumes, we now have the first American edition of Sade’s major and representative works and an excellent one. Relentlessly shocking, these explorations — fictional and otherwise — of eroticism, perversity, evil, and ugliness, show the Marquis de Sade at his best. Whether he is cataloguing sexual vices as in The 120 Days of Sodom or flaying sentimentality in a tale like Florville and Courval we see a mind dedicated to truth and to style.” — Library Journal

The eleven volumes of My Secret Life are a unique document… They show us that amid and underneath the world of Victorian England as we know it… a real secret social life was being conducted, the secret life of sexuality.

My Secret Life reveals to us the workings and broodings of a mind that had for an entire lifetime been possessed by a single subject of interest. It further reveals to us… how, during the Victorian period, a man who tried directly to deal with the demons of sexuality lived and felt and thought. That in itself… is triumph enough.

— Steven Marcus, The Other Victorians (Basic Books, 1966)

Incomparable in its detailed and accurate description of what we call human sexual response. If it is not only legitimate but valuable to express what people know, and obviously they know the appearances and sensations of their bodies, then My Secret Life is a valuable book.

— Mary Ellmann, Book Week

Complete title: SADOPAIDEIA, Being the experiences of Cecil Prendergast undergraduate of the University of Oxford. Showing how he was led through the pleasant paths of Masochism to the supreme joys of Sadism

***

“This play might be described as ‘Sade seen through women’s eyes,” writes Yukio Mishima in his preface to this fascinating play. Mishima had become intrigued by the riddle of why the Marquis’ wife, who remained devoted to him through through all the years of his wild misadventures and imprisonments, decided to leave him at the very moment he regained his freedom after the French Revolution. Although based on history, various facts in the play have been altered to suit the author’s dramatic purpose. While Sade himself never appears, he is an omnipresent specter: Mishima has said that he tried to place Madame de Sade at the center of his all-female drama, but in another sense, the real center is Sade himself, and it is around him, and his off-stage actions, that the drama revolves and coalesces.”

Redolent of the exquisite patchouli in the works on those unknown delineators of the strange and delicious bizarreies of the already upright Victorians, Harriet Marwood, Governess assumes its rightful place in the canon of letters dealing with the crepuscular world of the dominated.

Richard Lowel, a mere child when he is brought under the tutelage of Miss Marwood, his governess, is conducted through a labyrinth of cruelty, pain, blood, welts, screams, moans, torture, bondage and — delight. His is the bitter cup of humiliation and degradation; his is the dry crust of whippings and cuffings; his, also, the ecstasy of contact with this governess, the twisted yet paradoxically gentle Harriet.

From a recalcitrant boy, who finds only pain in his frequent batterings, Richard progresses to a stage where he begins to equate the torture of his body with his love for Harriet. In scrupulous detail, the reader is given an obsessive narrative in the usages of physical penalties to create a need, even an addiction, for more, and yet maddeningly more of the same.

Richard’s need to remain chaste for his beloved governess; his strangely feminine traits, brought more to the fore by the ministrations of his beauteous tutor, herself a devotee of sapphism; his perverse attachment to the actual objects used to inflict pain upon him: all these things make this book read like a sequel to the famous Venus in Furs.

A curious exploration of the Puritan ethic carried to its extreme conclusion, Harriet Marwood, Governess is a work which should be in the hand of all those who are deeply concerned with the problems brought by the alarming ascendance of woman in modern Western society.

***

Although exhaustive scholarship has proven futile in unearthing the true author of Harriet Marwood, Governess, there is enough evidence, textual and cultural, for us to assume its composition to be autobiographical. Whether written by the dominator or the male submissive, however, is totally unknown. Some of the delicate descriptions of furnishings and clothing have led commentators to assume a woman’s hand, yet the graphic attention paid to the details of whips, harnesses, and straps lead other researchers to the conclusion that the book was written by a man, “perhaps a horseman,” Dr. Fritz Beobachter notes. Whatever, its author is remarkably well hidden behind a veil of crisp British prose.

The full text of all issues of THE PEARL the underground magazine of Victorian England

The Pearl made its debut in London in July, 1879, the self-proclaimed journal of unblushing erotica for every taste. It flourished on the subterranean market until December, 1880, when it vanished as mysteriously as it had appeared. Included in the eighteen issues were six serialized novels that are standards of the black literature of the time (“Lady Pokingham, or They All Do It,” “Miss Coote’s Confession,” etc.), as well as the meatiest limericks then current, parodies of Robert Burns’ Merry Muses, ballads of epic sexual adventures, countless ditties, witticisms, jokes, letters from “readers,” and a potpourri of the scatological and scandalous gossip of the day.

Barney Rossett’s personal copy of The Pearl, “Printed for the Society of vice, 1880.” Nine decades later, when Lyndon Johnson was President, the Grove Press edition went through nineteen printings in twenty-one months.

From the Publishers of The Pearl

Venus School-Mistress is a collection of fiction, verse, drama, and philosophy on the theme of flagellation. In the tradition of My Secret Life, A Man and a Maid, and The Pearl, Venus School-Mistress includes such varied selections as the romantic recollections of Betsy Thoughtless; the fustigating philosophy of Thackeray Paedagogus; a story in verse about the adventures of Miss Agnes Sophonisba Snell, the Butcher’s Daughter, and her instructor, Mr. Mountwhackaway. The blend of gentle humor and grim fun in Venus School-Mistress is nothing short of delightful.

The present volume is reproduced from the 1917 edition, which was reprinted in turn from the 1788 edition. The reader, while enjoying the antiquated style and cadences of the text, can also take his pleasure in a constant discovery of the whimsical and amusing mistakes made by both printers.

In 1797 there appeared an enormous, ten-volume work, illustrated with a hundred and forty-two engravings, which must be classified as one of the most extraordinary works of literature ever written.

The work is divided into two parts, of which the first, entitled The New Justine, or the Misfortune of Virtue, comprised four volumes and represented the Marquis’ reworking of two earlier versions of the same tale; the second, in six volumes, was called Juliette, her Sister, or the Prosperities of Vice. Together they form the panels of an immense diptych, perhaps unrivaled in all literature — interrelated but distinctly opposite sides of the same coin.

If Justine is virtue personified, her sister Juliette is the embodiment of evil — perversity and crime exalt her: “I confess I love crime,” she declares, “only crime can stir my feelings.”

When Suburban Souls was published in 1901, the outspoken frankess of its autobiographical disclosures quickly made it as sought after as My Secret Life. But the edition was strictly limited and has never been been reprinted. G. Legman lists it as one of three most rare sexual memoirs ever published.

The author identifies himself only as Jacky S…. a forty-three year-old broker with the Paris stock exchange. His memoirs relate the story of his love affair with nineteen-year-old Lilian Arvel, which lasted five years…

Published in four volumes, issued between 1873 and 1876, The Romance of Lust introduces a little-known hero from the back passages of Victorian literature. Charles Roberts, better equipped than most men for the glorious battles of love, is himself a great user of “back stairways,” “doors of communication,” “peep-holes,” “secret little nooks,” and all the other structures quirks that combined to make life amusing in the staid formality of a Victorian mansion.

As a quivering lad of fifteen, suffering from the malady of frequent and unaccountable “bulges,” Charlie is at last taken in hand by a married lady, Mrs. Benson, who is visiting his mother’s house. More, she becomes his full initiator-instructress and launches him on an amorous career that spans a lifetime…

This is the erotic autobiography of a famous ex-member of the House of Lords, a pillar of the Church of Englang who was never known to be a libertine. Yet his memoirs show that he was, indeed, just that. Tracing his sex history from the time he was an inquisitive child through his sophisticated years as a mature man, the author reveals that he was a man who thought of a woman as the first consideration in life. His boyhood adventures began among the twelve-year-old girls of his neighborhood, who were not very advanced for their age; his fondness for them ended when they became concerned about “making babies by mistake” and when he had the good fortune to be in the path of a mature woman was seeking a fling. As idyllic as the beginning may have been, he became, as a young man, a devotee of every form of erotic gratification, yet at no time did he lose interest in relating with scientific precision the exact nature of whatever form his sexual satisfaction assumed.

“A manual for the masses, by one who was a Prince in the Peerage of Pornographia!””

— Fritz Beobachter, Ph.D.

This [The New Ladies Tickler] is one of those extraordinary books from Victorian times in which the characters absolutely refuse to be unhappy. They know nothing of regret, despite their outrageous conduct, but find excitement, joy, and love by resolutely pursuing their desires to the very end. There are two couples: Lady Lovesport, the widowed mistress of a vast estate, and her tireless lover, Mr. Everard; Lady Lovesport’s niece, Emily, a delightfully virginal and curious young girl of quality, and her lover, Harry, who is audacious. At first the youngsters find their way to each other, but are soon taken in by the older couple to form a close-knit circle in which flogging is not the least of the excesses.

“This unpretentious little book is truly a block-buster of a novel and deserves to be a best-seller.”

— Fritz Beobachter, Ph.D.

The classical dictum that literature must have a dual function — to please and to instruct — is delightfully realized in this eighteenth century work that provocatively combines a teasing sensuality with philosophical concerns. The formal, witty language of the period and the anticlerical metaphysics of the Enlightenment combine with sexuality to form a libertine exuberance typical of 1748, when the book was first published.

The first-person narrative by Therese is the charming tale of an innocent’s initiation into sexual happiness. Self-discovery in a convent leads her to her confessor, Father Dirrag, and she is soon launched upon the path of reason that convinces her that passion and love of the Deiety are equal gifts of God.

***

Thérèse philosophe was there, a charming performance from the pen of the Marquis d’Aergens, alone to have discerned the possibilities of the genre, though only partially realizing them; alone to have achieved happy results from the combining of lust and impiety. These, speedily placed before the public, and in the shape the author had initially conceived them, finally gave us an idea of what an immoral book could be.

— Donatien-Alphonse-François, the Marquis de Sade

NB: Concerning the matter of Harriet Marwood, Governess, this book was not, in fact, a lost Victorian novel, erotic or otherwise. In truth, it was written by the contemporary Canadian writer, poet and translator, John Glassco (1909–1981). The reason for this subterfuge is unknown but the anonymous Grove Press editor — Gilbert Sorrentino — responsible for writing the jacket copy plainly had fun with it. That same year, 1967, John Glassco was credited for his completion of Aubrey Beardsley’s unfinished Tännhauser parody, Under the Hill.

There’s something else that must be also told: “Fritz Beobachter, Ph.D.,” ponderer of Harriet Marwood’s authorship and later blurb other Grove erotica titles does not exist — he’s a fake. Presumably he was Sorrentino’s invention — it’s known he wrote the jacket copy thanks to his bibliographer, Stanford librarian William McPheron — but Fritz’s subsequent appearances on books without any known Sorrentino connection is a mystery. Perhaps Fritz became an in-house joke, usable by any dirty book jacket copy writer who had his number, or maybe Sorrentino himself had a hand in these other voluptuous efforts.

BOOK COVERS at HILOBROW: INTO THE GROVE series by Brian Berger | FILE X series by Josh Glenn | THE BOOK IS A WEAPON series | HIGH-LOW COVER GALLERY series | RADIUM AGE COVER ART | BEST RADIUM AGE SCI-FI | BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI | BEST NEW WAVE SCI-FI | REVOLUTION IN THE HEAD.