THIS: Small Wonder

By:

June 12, 2017

When you’re able to stop listening, it begins to make sense. For at least its opening half-hour, the first big-screen Wonder Woman movie tells its story all too literally — with two heavily voiceovered flashbacks, and the characters in-between reciting their backstory as thrilling athletics and grand scenery rush by. We’re marching through the linear saga of Diana’s upbringing on the Amazons’ supernatural island, and her people’s abrupt collision with the world of males when Steve Trevor’s warplane crashes there; in the beginning is the words, much more of them than cinema’s sensory storytelling should need. That’s how the unitary male god created the world, and the movie works best at the times it’s able to rise up from under the perfunctory spoken script’s labeling. In this context it seems uncoincidental that the director is female and the three credited screenwriters are men; it’s frequently left to Patty Jenkins to elicit a rich palette of facial expressions from the cast to compensate for often-leaden writing and long verbal blanks.

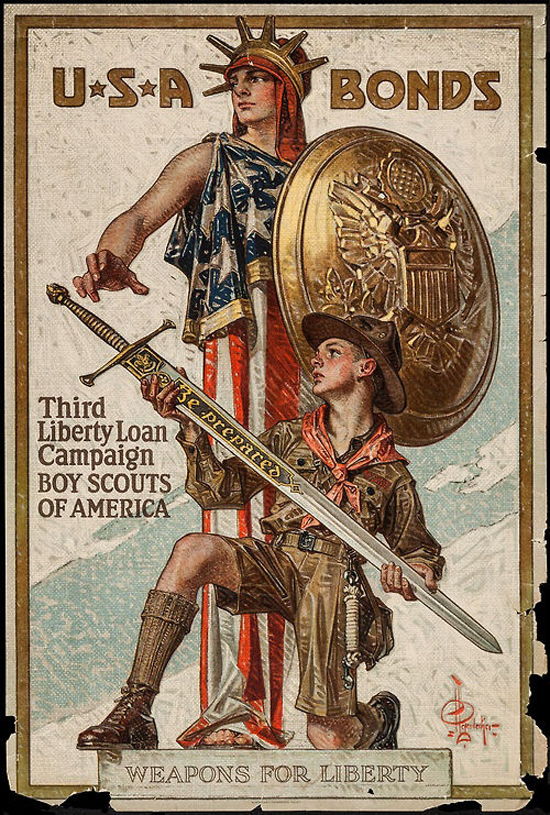

A generation of silent-film directors had to depend on this too, and it’s fitting that the action is set during World War I; it was a time of tectonic events and broad swaths of feeling, with comprehension struggling to catch up. The dialogue and narration from Allan Heinberg, Zack Snyder and Jason Fuchs mostly serve to caption the story like the title-cards they might as well be, though in that era there would have been fewer of them. The visuals can carry a lot of this on their own, and higher; Wonder Woman’s likeness most invokes the civic goddesses seen spurring soldiers on in WWI propaganda posters, so she goes well with the territory. And it is settings and situations that triumph in painting the movie’s meaning.

Midway through, when Diana and a pickup band of partisans liberate a Belgian town, we only need the imagery of the sparingly sweet, fleetingly celebratory aftermath to know that this is an oasis in time as precious, and isolated, as the island culture Diana comes from is in the middle of the ocean void. Her troupe includes a PTSD’d sniper from Scotland, a Moroccan master con-man and dandy hiding the scars of prejudice, and a Native American ordnance-smuggler living out a one-man diaspora; together with uncommonly noble (and unfashionably fatalistic) whiteguy Trevor and anomalously self-possessed woman Diana, we can see the temporary mirage of peacefulness as a counterpart to Huck and Jim’s raft as the only place such outcasts can belong with each other.

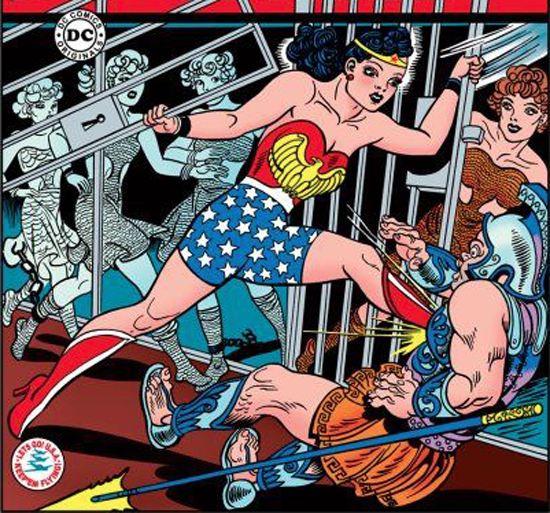

The farther you get into the movie, the more you’re able to detach these symbolic experiences from a descriptive armature. Jenkins succeeds in making Diana’s battles an ideal of wrathful grace rather than standard 300-style bloodshed (another case of gender mattering to both subtext and surface). The spectrum of youthful righteousness, trampled idealism and clear-eyed compassionate maturity is written on Gal Gadot’s face, as is the moral drift, haunted heroism and redeeming self-immolation on Chris Pine’s; two utterly committed and emotionally attuned performances pulled by Jenkins from these actors’ inner integrity, even when the words they are given to speak fail them.

Diana’s late-stage confrontation with the personified god of war does indeed provide some wise dialogues on the cases for and against human survival; though here too, the themes of mortal self-determination and will to live, and divine ego and manipulation, speak most clearly in the sheer pyrotechnic morality-play of the two characters’ battle of embodied ideas. Diana tells Ares that the flawed, hostile humans “are everything you say — but they are so much more,” and what I think she’s trying to express is that the capacity for choice and change makes mortals an improvement on the gods’ limitation to singular attributes and circular life stories. When pleading with a demoralized Diana to intervene on humans’ behalf, Trevor appeals to her disillusionment by saying, “You think I don’t get it? With everything I’ve seen?” By the end, from what the movie has shown us, we do piece together a picture of humans’ uneasy balance of benevolence and cruelty, and why both men and goddesses would give their lives to weight those scales. Even the works of heaven are not without imperfection, and Wonder Woman’s message of acceptance can rise above mere voices. Don’t believe me, believe your eyes.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2023 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE