THIS: Consumer Culture

By:

January 30, 2017

Scarcity is a preoccupation of overabundant societies. American liberals used to be demonized for insisting on “an age of limits,” but everything the entire country does has always been based on the (consensually unspoken) premise that the way we live can’t last.

Nobody overindulges because they think supplies will never run out; they binge because all things (not least time) will. The colonial world has used up sugar-plantation upon smartphone-sweatshop, and eventually there will be nowhere else to go.

Hence, our emphasis in horror stories of it all coming home. Soylent Green, in which we ourselves end up as the food supply, was a paradigm, coming not uncoincidentally during a decade of shortages and imperial retreat for America, the 1970s. It shares this not-so-subtext with persistently popular zombie fiction.

The dog-eat-dog metaphor that isn’t a metaphor goes at least as far back as Swift’s Modest Proposal in the 1700s and the penny-dreadful Sweeney Todd legend in the 18s, both underlain with class anxieties. It’s as old as predatory social organization itself, though our self-conscious position as the sole evolutionary superpower, so to speak, has heightened 21st century humanity’s sense of impermanence and self-consumption as our fields dry out and the oceans threaten to leave whole cultures swallowed up.

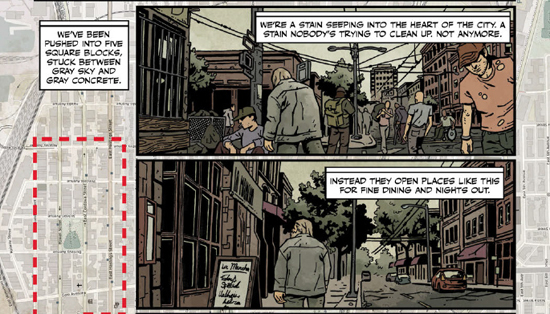

Swift is quoted directly toward the beginning of The Dregs, a comic from Black Mask Studios that debuted last week. This dissident thriller follows a semi-delusional protagonist in a barely-believable reality; the homeless, drug-addicted detective-novel fan who’s looking for a disappeared friend in a city where the poor are being devoured literally by patrons of the gentrified establishments that are eating up the neighborhood.

The narrator’s interior voice, a secret nested within a society-wide silence, is recorded well by writers Lonnie Nadler and Zac Thompson; the plodding yet tense existence of homeless district “The Dregs”’ denizens is paced out with poetic brevity by artist Eric Zawadzki, and the story’s squalor is observed with perceptive, ragged detail by Zawadzki and color-artist Dee Cunniffe, whose sense of extreme but optically faithful lighting and raw, psychologically true tinges of experience is second to none. (The visual atmosphere has a special nostalgia for me, resembling as it does Pasquale PAKO Massimo & Barbara Ciardo’s work on the comparable class-war parable The BodySnatchers, whose English-language adaptation I worked on; it’s always good to see something live on.)

The DIY detective, Arnold, tries to trace patterns that no one else can see, though he’s walking in footsteps he may not be aware of; Arnold’s searching of bombed-out lots and absent people, an odyssey through what isn’t there, is reminiscent of the obsessive urban march (and amateur detective-work) of the main character in Paul Auster’s novel City of Glass (who also makes charts based on certain pedestrian movements, and ends up a person of the streets); it also recalls the witness to decline (and once again, eventual homelessness) of the narrator in Arthur Nersesian’s The Fuck-Up. Both those prose novels dramatize the Reagan era of a New York transformed from dystopian wasteland to sanitized affluent playground; City of Glass actually came out at the time and thus reports on a spiritual emptiness in-progress; The Fuck-Up is set in that period but was published a decade later, thus looking back across an abyss; kindred to that earlier time when the social plate was being cleared, so to speak, The Dregs arrives at our own unprecedented point of inequality, moving forward uncertainly from a starting point at the abyss.

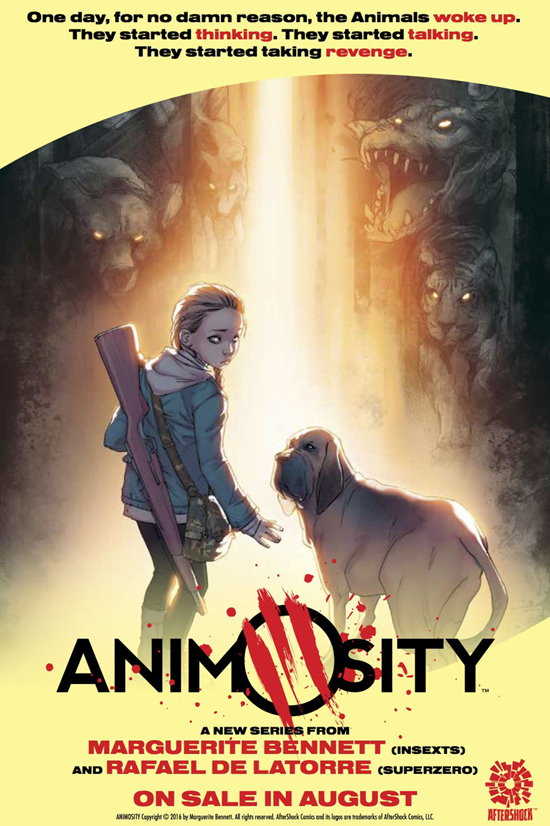

The other defining parable of class upheaval is, of course, Orwell’s Animal Farm, in which the food-chain itself rises up against us. This modest proposal is experiencing its own logical conclusion in the hit comic Animosity from AfterShock, by writer Marguerite Bennett and artist Rafael de Latorre. Since we fear oneness almost as much as we fear otherness, the machine-intelligence Singularity is a competing pop phobia of the current moment; Animosity turns this upside-down with a spontaneous, worldwide awakening of consciousness and speech amongst all the planet’s “lower” species.

Rather than the friendly talking-doll fantasy of countless cartoons or the cognitively distinct nascent languages of the lab-animal heroes in Morrison & Quitely’s We3, the “pets” and “livestock” and “circus attractions” and others in Animosity all suddenly speak like humans and flip their typical roles for a kind of freed-from-the-Matrix pissed-off militancy. Vengeance for past slaughter, exploitation or even just condescension is what’s most on their minds, but primarily so that space can be cleared for their autonomous existence; there aren’t humans in pens being fattened for food or bred for research as in a Planet of the Apes or Kamandi, so the horror for the dominant class here is not that of being used but of not being needed (i.e., the panic that whitefolk feel when some play or TV show has a full cast of color).

Unlike in those last two talking-animal epics, the characters in Animosity do not develop opposable thumbs and upright gaits; more resembling the cutely creepy animals of Victorian illustration, they make do with the appendages and abilities they have (arguably a reversal of the balance between high ability and low awareness that real-life humans exhibit). The point-of-view character for the homo sapiens in the audience is Jesse, a little girl of great intellectual resources and inextinguishable goodwill who’s orphaned and traveling through the harsh chaos and embattled fiefdoms of the new natural order with Sandor, once “her” family dog. (Jesse’s presence is itself a welcome evolution from the boy hero of Kamandi, until recently a disproportionate commonplace that said something about who we do and don’t assume to be persons even within our species.)

Many of the once-supreme humans are hostile, and even more are dead, but Jesse and a few others accept the idea of a balanced, equal world — though this new, fragmented animal kingdom is not always any less in conflict than it ever was. Bennett’s catastrophic imagination and empathetic vision are each on overdrive, making this one of the most outrageous and compassionate of popular entertainments, breaking crazed philosophical ground. The civilization of Animosity has been thrown into an upset whose resolution no one can foresee (if that sounds familiar), but in the meantime, its scenarios of compulsory herbivorousness speak amusingly to traditionalist tofu-ophobia even as its themes of realigned (or obsolete) hierarchies project a progressive model of the majority-minority society we’ll all soon have to live in (if we do at all). It’s reassuring to see something for everybody, even if there isn’t ever enough.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2024 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE