THIS: Playing Ourselves

By:

December 19, 2016

Sad stories are the ones we never need to hold on to. It’s joy that feels elusive, whose details start escaping us soon after we live them, while sorrows write themselves on our memory in a story that never changes. But if we tell them, then others might hear as they pass us and not have to go down the same path.

Other people’s sadness is hard to grasp, especially when stories never known the first time float free like dark clouds without a shadow. A cold wind was cutting down a barren city street one winter season as my family and I walked home and stopped to sign some shivering protestors’ petition to remove then-President Nixon for the bombs he was bringing Southeast Asia for Christmas; this memory blows back to me as I think about The Plain of Jars, a new opera by Keith Patchel whose first life I witnessed in a small walkup theatre on another dark December street.

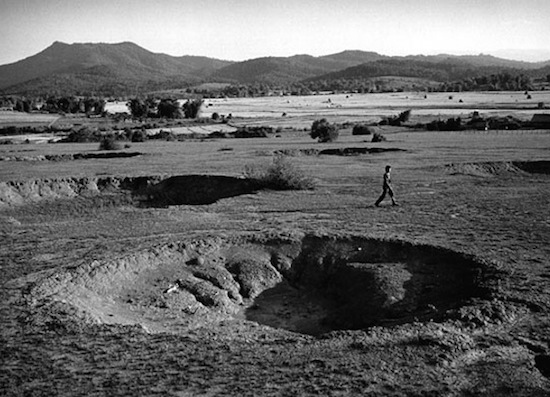

This was about the part of Nixon’s war that wasn’t being watched nightly at the time; the secret bombing of Laos ostensibly to block safe havens for the “enemy” in Vietnam, and more practically to test new weapons on a whole conscripted landscape and its innocent lives. The Plain of Jars is named for the ancient funerary structures strewn about it, like empty maws turned up toward the predatory metal birds of America, dropping down more death.

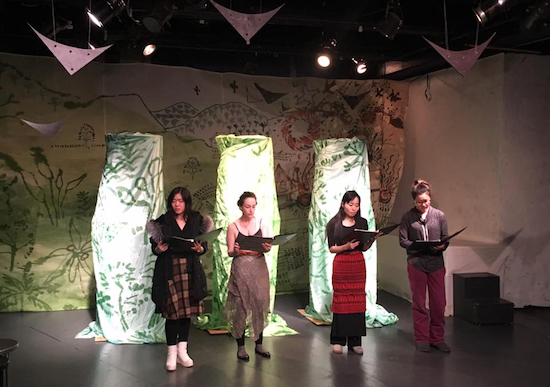

A mobile of modernist avian structures hangs at random intervals above the opera’s set, casting shadows that could seem ominous or uplifting. Symbols and surfaces of unstable meaning populate the stage, as we see magic-realist meetings of the pivotal figures in the U.S. halls of power and archetypal choirs of the powerless, prophetic everyday people on the killing field.

A phantom Mount Rushmore of JFK, Lyndon Johnson, Nixon and Henry Kissinger conspire in ways they wouldn’t have in reality (a relative term) but which tell truths about the continuity of their folly. A quartet of Laotian women bardically sing as caretakers of their culture and chroniclers of the nightmare their life has become.

The psychic echo that bounces off the empty walls of Aleppo is resounding, and the improvisation of existence is serendipitously expressed by the intuitive spontaneous composition of many of this choir’s solo melodies (one of the most lovely and resourceful voices among them, Clara Francesca, told me that much of the score had fallen victim to a computer crash and thus had to be fashioned as it was performed).

The men read from librettos like they’re delivering their own eulogies; Timothy McCown Reynolds conveys Nixon’s bombastic gravitas without caricature and John Hayden doesn’t even attempt a Kissinger accent or posture, instead embodying the slick global man of mystery Kissinger fancied he was; a precise performance by an actor playing a public figure who is playing himself. The cast list refers to these distant mirror images as “a Richard Nixon,” etc., and as “a” John F. Kennedy, Robert E. Turner is a heartbreaking, blustering martyr, his own crumbling statue to himself, or as he puts it, “the crucifixion of democracy.”

An opening scene that exists out of time, with the worse angels of Nixon, LBJ and Kissinger in the same room with the not-nearly-as-bad angel of Kennedy, is one of the eeriest things I’ve seen on a stage; some other scenarios with Johnson and cynical CIA agents rang as cartoonish simplification to me, missing the complexity of their true perversions of civic duty — we don’t all remember the same things, but that’s what happens when you don’t get told to begin with.

The show is stopped (though the world hurries on) with a lengthy aria of lament and recrimination sung by Yang Xi as a voice of the Laotian people and the wounded world, left behind at a historical crossroads many still don’t even know was passed by. A vocal painting of pure pain and invincible humanity and undeterrable witness like nothing I’ve ever heard, it is an ill, melodic wind that might once have reached me on that freezing night of America’s soul 44 winters ago.

Other shadows are cast shorter, but may follow us for no one knows how long. I found myself unexpectedly nostalgic for a story ostensibly about the future (or as Patchel might say, a future), as I was catching up on The Brooklynite, an online comic connected to three others (one of which, full disclosure, I write) about the iconic borough mystically splitting off from the New York mainland, drifting out to sea, and establishing itself as a progressive sovereign state. Division doesn’t get more literal than this, though the feelings of mainstream estrangement and utopian restart are more vivid in the weeks since the 2016 election than they were at the time the Brooklynite series was being conceived by the late Seth Kushner.

Concerning a comic-creator who ends up with superpowers due to one in a string of bizarre accidents of which the borough’s seismic breakoff is just the first, the parallels to Seth and his studio-mates are clear; “Jake Jeffries” is playing Seth and Seth was partially spoofing himself, though both versions are taking a look at who they really are (the scenes of slow maturation and perennial psychoanalysis have a lot of counterparts in Kushner’s autobiographical volume, Schmuck).

Seth’s departure was a single death, but it was surrounded by another kind. The reshaping of the Brooklyn landscape by post-industrial, not military-industrial powers through gentrification, is making some of The Brooklynite’s settings vanish around it. The real-life warehouse studios that Jake works in are a vivid memory of haven for myself when I was first adrift from the death of most of my own family and taken in by my artistic one, but this site is also already just a memory, as the whole creative community in that structure was evicted before the end of this past, deadly year.

What’s left behind is a sketchbook testament to everything that lives on in love and memory; fleshed out and finished by artists Shamus Beyale and Jason Goungor, Seth’s storyline unfolds amidst the vaulting arches and entablatures of Brooklyn’s grand, shabby brick-and-mortar monuments, stone shells like those jars in Laos, waiting to be filled with future gifts.

Scrolling down with spectacular humility, these scenes do for the oblong graphic canvas what Jack Kirby’s print-media spreads did for the panorama, and their colors and consequences burst like some magic parchment. Such frames can crumble and blow away, and only the wind may one day sing…but voices released have no barriers, and there’s no erasing what we know by heart.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2024 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE