THIS: Ex-Deus

By:

June 6, 2016

Universal Robots by Mac Rogers, revived and revised at The Sheen Center for Thought and Culture, through June 26, 2016

We all hope for a second draft of history. Authors and dramatists seek to rewrite the present. In Mac Rogers’ play Universal Robots, history and fantasy switch places, and only we outside the frame fully know how that’s likely to work out. The spiral is brilliantly conceived and thoughtfully navigated by Rogers, who is both reworking Karel Capek’s play of a very similar name, and re-engineering Capek’s own biography and context. Written by and about a playwright with political leanings, Universal Robots also considers whether stories can change the world, or if life’s compromises just change the story we tell.

Believing your own story is different than making it come true, too. In the play’s reality, “Rossum’s Universal Robots” is a real company in 1920s Czechoslovakia, and the world is really faced with choices involving the purpose and rights of a new, artificial life form. Though not the world at first — the intellectual clique at an informal barroom salon that Capek frequents is visited by a young woman and the adult-size automaton she wheels in. The woman is Rossum’s daughter, who happens to be a fan, and offers this lifeless type of serf as an alternative to the oppressable classes she’s seen allegorized in a play by Capek and his sister Jo (transposed from his real-life brother in one of the narrative’s most beneficial glitches in the matrix). The small band of writers and one inventor travel back to the lab of head scientist Rossum herself (widow of the man in the original play, and the real brains of the partnership), whereupon another tight circle, now including Czechoslovakia’s first democratic president Tomas Masaryk, finances and aids Rossum in developing her “robots” (actually a genetically engineered drone class) while Karel and Jo formulate the ethics they and the robots should observe. Back at the bar, the endless argument had been over the gap between writing about social ills and taking genuine action; in the most vivid of hypotheticals for this, Capek here has crossed from fiction into the murky center of his own cautionary tale.

Like all technological advancements, the robots end up not just with domestic but military roles, and as in Norman Spinrad’s The Iron Dream (another speculation on a world without a second war), we are left with a sad conviction that, no matter the conditions, what “should” have been is not what would’ve — the 20th century stays just as bloody, just in another way. The irony, of course, is that the dangerous variable in the equation is the human factor itself; an impurity that comes under the robots’ verdict as in many such modern fables, though never this self-critically.

That damned-whatever-you-do feeling is borne by Masaryk, who weighs within himself the balance between bloodshed and preserving civil society (as he did in turning back a Communist revolution); in one remarkable early scene the radical Vaclavek, another regular in the Capeks’ saloon circle, gets to debate Masaryk face-to-face when the president stops by; a stunning reminder of how removed our own century’s rulers are from their people, and a compellingly relevant dialogue during this election year’s establishment/insurgency tensions and its elusive equilibrium between pragmatism and principle.

Unlike Masaryk, Karel’s flaw is in believing his purpose is to give answers rather than pose questions; Jo remains a questioner, which isolates her to a degree it’s best to see the play to find out. Suffice it to say that not every overthrow is a downfall, and it’s no spoiler to note the sense in much robotic fiction that others could inhabit a set of feelings and judgment that modern humans seem to have abdicated.

In Universal Robots the self is divided along with the labor; brother and sister split over ethical differences, the mirror-image between human and robot becomes a wider gap, the gulf between social identities (communist, democratic, fascist) grows. Past is severed from future, too; the whole play unfolds in hideouts of a sort, but the intelligentsia’s barroom feels unreclaimably far away from the bunkered robot-production compound from which the old clique directs social upheavals rather than daydreaming more perfect worlds. Innocent expectation turned to regretful, even horrific outcomes are a common undercurrent in Rogers’ work; in another division, the characteristic time-jump across an intermission embodies feelings of titanic loss that never lose sight of intimate consequences; Rogers is a poet of long aftermaths.

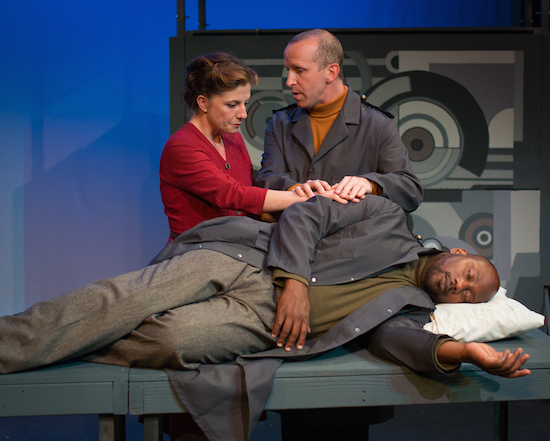

Universal Robots is an attempt to answer some of the challenges he himself throws out. Early in the show, a colleague decries the Capeks’ reluctance to populate their plays with “actual people rather than solipsistic symbolic cyphers.” But there is no loss of genuineness and individuality among this production’s superlative cast. As Karel, Jorge Cordova radiates a fragile hubris as sympathetic as it is hazardous; Hanna Cheek’s incarnation of Jo is a performance of phenomenal sensitivity and forbearance; Tandy Cronyn as Rossum is a giant of brittle neediness and mischievous insight (she should be the next Sherlock Holmes); Sara Thigpen as Masaryk gives a portrait of principled, burdened leadership and conflicted duty and humanity we can only hope for in our real-world rulers; Tarantino Smith as Vaclavek embodies the dignified passion and disfigured empathy of the revolutionary in an absolutely magnetizing way; Jason Howard, as the original sentient robot, creates an utterly original image of alienness that our inner, isolated selves will feel all too familiar (and later, a harrowing, compassionate portrayal of trauma and emotional dissonance that is only new to him); and Nikki Andrews-Oja is aglow with contained, explosive charisma and commanding serenity as the leader of the android army and the narrator of the tale.

That narration frames the tale from an imagined future, with a twist that dedicated sci-fi fans will see coming, but be delighted and uplifted by when it arrives. Jo had wanted this new lifeform to remain an art and not a science, and her voice is heard at the end too, in an inspired way that you should also see for yourself. All I need to say is that, in its sad and satisfying conclusion, Universal Robots affirms the value of telling stories to each other and ourselves, as long as we choose the right ones to tell.

Photos: Deborah Alexander

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2024 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE