A Rogue By Compulsion (10)

By:

June 4, 2016

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

I woke next morning at seven, or perhaps I should say I was awakened by Gertie ‘Uggins, who to judge from the noise was apparently engaged in wrecking the sitting-room. I looked at my watch, and then halloed to her through the door. The tumult ceased, and a head, elaborately festooned with curl-papers, was inserted into the room.

“Yer want yer barf?” it asked.

“I do, Gertrude,” I said; “and after that I want my breakfast. I have a lot to do today.”

The head withdrew itself, tittering; and a moment later I heard a shrill voice calling down the kitchen stairs.

“Grahnd floor wants ‘is ‘ot water quick.”

Within about five minutes the ground floor’s wish was gratified, Mrs. Oldbury herself arriving with a large steaming can which she placed inside a hip bath. She asked me in a mournful voice whether I thought I could eat some eggs and bacon, and having received a favourable reply left me to my toilet.

It was about a quarter to eight when I sat down to breakfast. Considering that for three years I had been obliged to rise at painfully unseasonable hours, this may appear to have been unnecessarily energetic, but as a matter of fact I was not acting without good reasons.

To start with, it was my purpose to spend a pleasant morning with George. I wanted to be outside his house so that I could see his face when he came out. I felt sure that as long as I was at liberty he would be looking worried and depressed, and I had no wish to postpone my enjoyment of such a congenial spectacle.

Then, provided that I could restrain myself from breaking his head, I intended to follow him to Victoria Street or wherever else he happened to go. Beyond this I had no plan at the moment, but at the back of my mind there was a curious irrational feeling that sooner or later I should stumble across some explanation of the mystery of Marks’ death.

I knew that as a rule George didn’t start for business until nine-thirty or ten. I was anxious to get out of the house as soon as possible, however, just in case I was correct in my idea that the gentleman with the scar was keeping a kindly eye on my movements. In that case I thought that by departing before half-past eight I should be almost certain to forestall him. If, as I believed, he was under the impression that I had been indulging in a night’s dissipation, it was unlikely that he would credit me with sufficient energy to get up before ten or eleven. As to waiting for George — well, I had no objection to that. It was a nice sunny morning, and I could buy a paper and sit on one of the embankment seats.

This, indeed, was exactly what I did. I slipped out of the house as unobtrusively as possible, and, stopping at a little newspaper and tobacco shop round the first corner, invested in a Telegraph and a Sportsman. Then, after making sure that I was not being followed, I set off for the embankment.

Some of the seats were already occupied by gentlemen and ladies who had apparently been using them in preference to an hotel, but as luck would have it the one opposite George’s house was empty. I seated myself in the corner, and after cutting and lighting a cigar with the care that such an excellent brand deserved, I prepared to beguile my wait by reading the D.T.

Nothing particularly thrilling seemed to have been happening in the world, but I can’t say I felt any sense of disappointment. Just at present my own life afforded me all the excitement my system needed. The only important item of news that I could find was a rather offensive speech by the German Chancellor with reference to the dispute with England. It was a surprising utterance for a statesman in his position, and the Telegraph had improved the occasion by writing one of its longest and stateliest leaders on provocative politicians.

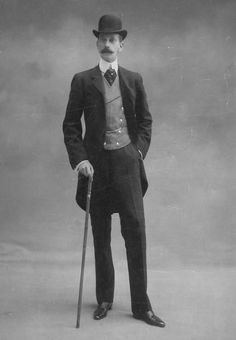

I had just finished reading this effort when George appeared. He came out of the front door and down the steps of his house, dressed as usual in a well-fitting frock-coat and tall hat, such as he had always affected in the old days. I stared at him with a sort of hungry satisfaction. He looked pale and harassed, and he carried his head bent forward like a man whose mind was unpleasantly preoccupied. It warmed my heart to see him.

When he had gone some little way along the pavement, I got up from my seat and began to keep pace with him on the other side of the roadway. It was easy work, for he walked slowly, and stared at the ground as though fully taken up with his own thoughts. I was not the least frightened of his recognizing me, but as a matter of fact he never even looked across in my direction.

We marched along in this fashion as far as Vauxhall Bridge Road, where George turned up to the left in the direction of Victoria Street. I walked on a bit, so as to allow him to get about a hundred yards ahead, and then coming back followed in his track. As he drew nearer to the station I began to close up the gap, and all the way along Victoria Street I was only about ten yards behind him. It was tantalizing work, for he was just the right distance for a running kick.

The offices of our firm, which I had originally chosen myself, are on the first floor, close to the Army and Navy Stores. George turned in at the doorway and went straight up, and for a moment I stood in the entrance, contemplating the big brass plate with “Lyndon and Marwood” on it, and wondering what to do next. It seemed odd to think of all that had happened since I had last climbed those stairs.

Exactly across the road was a restaurant. It was new since my time, but I could see that there was a table in the window on the first floor, which must command a fair view of the houses opposite, so I determined to adopt it as a temporary scouting ground. I walked over and pushed open the swinging doors. Inside was a sleepy-looking waiter in his shirt-sleeves engaged in the leisurely pursuit of rolling up napkins.

“Good-morning,” I said; “can I have some coffee and something to eat upstairs?”

He regarded me for a moment with a rather startled air, and then pulled himself together.

“Yes, saire. Too early for lunch, saire. ‘Am-an’-eggs, saire?”

I nodded. I had had eggs and bacon for breakfast, and on the excellent principle of not mixing one’s drinks, ‘am an’-eggs sounded a most happy suggestion.

“Very well,” I said; “and I wonder if you could let me have such a thing as a sheet of paper, and a pen and ink? I want to write a letter afterwards.”

This, I regret to say, was not strictly true, but it seemed to offer an ingenious excuse for occupying the table for some time without arousing too much curiosity.

The waiter expressed himself as being in a position to gratify me, and leaving him hastily donning his coat I marched up the staircase to the room above.

When I sat down at the table in the window I found that my expectations were quite correct. I was looking right across into the main room of our offices, and I could see a couple of clerks working away at their desks quite clearly enough to distinguish their faces. They were both strangers to me, but I was not surprised at this. I always thought that George had probably sacked most of the old staff, if they had not given him notice on their own account. Of my cousin himself I could see nothing. He was doubtless either in his own sanctum, or in the big inner room where I used to work with Watson, my assistant.

It was of course impossible to eat much of the generous dish of ‘am-an’-eggs which the waiter brought me up, but I dallied over it as long as possible, and managed to swallow a cup of rather indifferent coffee. Then I smoked another cigar, and when the things were cleared away and the writing materials had arrived, I made a pretence of beginning my letter.

All this time, of course, I was keeping a strict watch across the street. Nothing interesting seemed to happen, and I was just beginning to think that I was wasting my time in a rather hopeless fashion when suddenly I saw George come out of his private office into the main room opposite, wearing his hat and carrying an umbrella. He spoke to one of the clerks as though giving him some parting instructions, and went out, shutting the door behind him.

I jumped to my feet, and hurrying down the stairs, demanded my bill from the rather surprised waiter. Considering that I had been sitting upstairs for over an hour and a half, I suppose my haste did appear a trifle unreasonable; anyway he took so long making out the bill that at last I threw down five shillings and left him at the process.

Even so, I was only just in time. As I came out into the street George emerged from the doorway opposite. He looked less depressed than before and much more like his usual sleek self, and the sight of him in these apparently recovered spirits whipped up my resentment again to all its old bitterness.

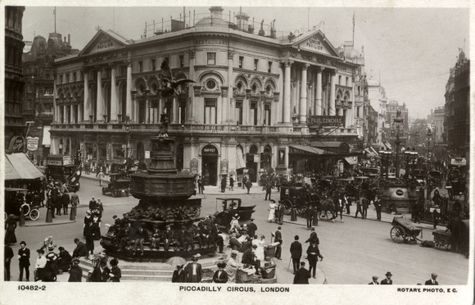

He set off at a brisk pace in the direction of the Houses of Parliament, and crossing the street I took up a tactful position in his rear. In this order we proceeded along Whitehall, across Trafalgar Square, and up Charing Cross Road into Coventry Street. Here George stopped for a moment to buy himself a carnation — he had always had a taste for buttonholes — and then resuming our progress, we crossed the Circus, and started off down Piccadilly.

By this time what is known I believe as “the lust of the chase” had fairly got hold of me. More strongly than ever I had the feeling that something interesting was going to happen, and when George turned up Bond Street I quickened my steps so as to bring me back to my old if rather tempting position close behind him.

Quite suddenly in the very narrowest part of the pavement he came to a stop, and entered a doorway next to a tobacconist’s shop. In a couple of strides I had reached the spot, just in time to see him disappearing up a winding flight of stone stairs.

There were two little brass plates at the side of the door, and I turned to them eagerly to see whom he might be honouring with a visit.

One was inscribed “Dr. Rich. Jones, M.D.,” and the other “Mlle. Vivien.”

The moment I read the last name something curiously familiar about it suddenly struck me. Then in a flash I remembered the pencilled notice on Tommy’s door, and the obliging “Miss Vivien” who was willing to receive his telegrams.

The coincidence was a startling one, but I was too anxious to discover what George was doing to waste much time pondering over it. Stepping forward to the foot of the stairs, I peered cautiously up. I could see by his hand, which was resting on the banisters, that he had passed the floor above, where the doctor lived, and was half way up the next flight. Whoever Mlle. Vivien might be, she certainly represented George’s destination.

I retreated to the door, wondering what was the best thing to do. My previous effort in Victoria Street had been so successful that I instinctively glanced across the street to see whether there was another convenient restaurant from which I could repeat my tactics. There wasn’t a restaurant but there was something else which was even better, and that was a small and very respectable-looking public-house.

If I had to wait, a whisky-and-soda seemed a much more agreeable thing to beguile the time with than a third helping of ham and eggs, so crossing the road with a light heart, I pushed open a door marked “Saloon Bar.” I found myself in a square, comfortably fitted apartment where a genial-looking gentleman was dispensing drinks to a couple of chauffeurs.

Along the back of the bar ran a big fitted looking-glass, sloped at an angle which enabled it to reflect the opposite side of the street. This was most convenient, for I could stand at the counter with my back to the window, and yet keep my eye all the time upon the doorway from which George would appear.

“Good-morning, sir: what can I get you?” inquired the landlord pleasantly.

“I’ll have a whisky-and-soda, thanks,” I said.

As he turned round to get it a sudden happy idea flashed into my mind. I waited until he had placed the glass on the bar and was pouring out the soda, and then inquired carelessly:

“You don’t happen to know any one of the name of Vivien about here, I suppose?”

He looked up at once. “Vivien!” he repeated; “well, there’s a Mamzelle Vivien across the road. D’you mean her?”

I shrugged my shoulders. “I don’t know,” I said; then, with a coolness which would have done credit to Ananias, I added: “A friend of mine has picked up a little bag or something with ‘Vivien, Bond Street,’ on it. He asked me to see if I could find the owner.”

The landlord nodded his head with interest. “That’ll be her, I expect. Mamzelle Vivien the palmist — just across the way.”

“Oh, she’s a palmist, is she?” I exclaimed. The thought of George consulting a palmist was decidedly entertaining. Perhaps he wanted to find out whether I was likely to wring his neck.

With a side glance at the chauffeurs, the landlord leaned a little towards me and slightly lowered his voice. “Well, that’s what she calls ‘erself,” he observed. “Palmist and Clairvoyante; and a smart bit o’ goods she is too.”

“But I thought the police had stopped that sort of thing,” I said.

The landlord shook his head. “The police don’t interfere with her. She don’t advertise or anything like that, and I reckon she has some pretty useful friends. You’d be surprised if I was to tell you some o’ the people I seen going in there — Cabinet Ministers and Bishops.”

“It sounds like the Athenaeum Club,” I said. “Do you know what she charges?”

“No,” he replied; “something pretty stiff I guess. With folks like that it’s a case of make ‘ay while the sun shines.”

He was called off at this point to attend to another customer, leaving me to ponder over the information he had given me. I felt that somehow or other I must make Mademoiselle Vivien’s acquaintance. A beautiful palmist, for whom George deserted his business at eleven in the morning, was just the sort of person who might prove extremely interesting to me. Besides, the fact that her name was the same as that of the lady who lived next door to Tommy lent an additional spur to my curiosity. It might be a mere coincidence, but if so it was a sufficiently odd one to merit a little further investigation.

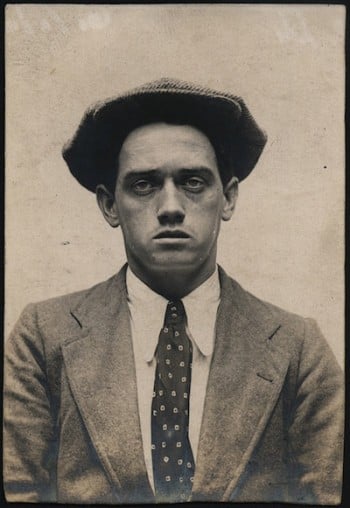

![Florence Lee [Fortune teller??]](https://www.hilobrow.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/tumblr_mkijvdmGix1rb5nc0o1_500.jpg)

I drank up my whisky, and after waiting a minute or two, ordered another. I had just got this and was taking my first sip, when quite suddenly I saw in the mirror the reflection of George emerging from the doorway opposite.

I didn’t stop to finish my drink. I put down the tumbler, and nodding to the landlord walked straight out into the street. The pavement was thronged with the usual midday crowd, but pushing my way through I dodged across the road and reached the opposite side-walk just in time to see George stepping into a taxi a few yards farther down the street.

I was not close enough to overhear the directions which he gave to the driver, but unless his habits had changed considerably the chances were that he was off to lunch at his club. Anyhow I felt pretty certain that I could pick up his trail again later on at the office if I wanted to. For the moment I had other plans; it was my intention to follow George’s example and pay a short call upon “Mademoiselle Vivien.”

I walked back, and throwing away the end of my cigar, entered the doorway again and started off up the stairs. I imagined that by going as an ordinary client I should find no difficulty in getting admitted, but if I did I was fully prepared to bribe or bluff, or adopt any method that might be necessary to achieve my purpose. I would not leave until I had at least seen the gifted object of George’s midday rambles.

I reached the second landing, where I was faced by a green door with a quaintly carved electric bell in the shape of an Egyptian girl’s head, a red stone in the centre of the forehead forming what appeared to be the button. Anyhow I pressed it and waited, and a moment later the door swung silently open. A small but very alert page-boy who looked like an Italian was standing on the mat.

“Is Mademoiselle at home?” I inquired.

He looked me up and down sharply. “Have you an appointment, sir?”

“No,” I said, “but will you be good enough to ask whether I can see her? My name is Mr. James Nicholson. I wish to consult her professionally.”

“If you will step in here, sir, I will inquire. Mademoiselle very seldom sees any one without an appointment.”

He opened a door on the right and ushered me into a small sitting-room, the chief furniture of which appeared to be a couch, one or two magnificent bowls of growing tulips and hyacinths, and an oak shelf which ran the whole length of the room and was crowded with books.

While the boy was away I amused myself by examining the titles. There were a number of volumes on palmistry and on various branches of occultism, interspersed with several books of poetry and such unlikely works as My Prison Life, by Jabez Balfour, and Melville Lee’s well-known History of Police.

It gave me rather an uncanny feeling for the moment to be confronted by the two latter, and I was just wondering whether a Bond Street palmist’s cliéntèle made such works of reference necessary, when the door opened and the page-boy reappeared.

“If you will kindly come this way, sir, Mademoiselle will see you,” he announced.

I followed him down the passage and into another room hung with heavy curtains that completely shut out the daylight. A small rose-coloured lamp burning away steadily in the corner threw a warm glow over everything, and lit up the low table of green stone in the centre, on which rested a large crystal ball in a metal frame. Except for two curiously carved chairs, there was no other furniture in the room.

Closing the door noiselessly behind him, the boy went out again. I stood there for a little while looking about me; then pulling up a chair I was just sitting down when a slight sound attracted my attention. A moment later a curtain at the end of the room was drawn slowly aside, and there, standing in the gap, I saw the slim figure of a girl, dressed in a kind of long dark Eastern tunic.

I jumped to my feet, and as I did so an exclamation of amazement broke involuntarily from my lips. For an instant I remained quite still, clutching the back of the chair and staring like a man in a trance. Unless I was mad the girl in front of me was Joyce.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.