Stuffed (12)

By:

May 27, 2016

One in a popular series of posts by Tom Nealon, author of the forthcoming Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste (British Library Publishing, September 2016). STUFFED is inspired by Nealon’s collection of rare cookbooks, which he sells — among other things — via Pazzo Books.

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

Salsa. Even the name, derived as it is from the ur-condiment, salsus (salted), speaks to us, echoes in our viscera. That’s maybe why I’ve avoided writing about it for so long — so many people have screwed up salsa, I’m not eager to be on that list.

They say that salsa is the most popular condiment in the U.S., and maybe it is, if there is an “it” — if “salsa” is one thing, that is to say. If there is one salsa, it is the result of it being jarred and canned and eroded for decades by the gears of mass production. And yet salsa survives and even thrives, after a fashion. So I’ve finally decided to explore salsa’s history.

Salsa’s story, I’ve discovered, starts a long time ago… in an unexpected place.

In the year 1210 AD, Hermann von Salsa, fourth Grandmaster of the Teutonic Knights, attended the coronation of John of Brienne as King of Jerusalem. He thought back to the last coronation he’d attended in Jerusalem: 1197, King Amalric II. Embarrassingly, he’d brought his squire as his +1, and compounded the error by forgetting to remove his spurs for the after-party. Luckily, that was before he had been made Grandmaster — and when he was still known as Hermann von Thuringia — so scrutiny was comparatively low.

Hermann had subsequently earned the sobriquet “Salsa” thanks to his extreme, even off-putting love (which he’d developed while in the Middle East) of Kamakh Rijal, a sour yoghurt sauce flavored with garlic and mint that is fermented in a gourd all summer. His plan to bring baba ganoush back to Prussia as an enticement for pagans to embrace Christianity, didn’t take: Eggplant, like potatoes and tomatoes, are a nightshade, so farmers thought it was poisonous and refused to grow it. Likewise, his plan to name a tributary of the Enns river near his home the Salsa River (he’d dreamed of it running thick with Kamakh Rijal), didn’t take. Today, however, they do call this Enns tributary the Salsa. Mistakenly, historians think that Hermann was named after the river, and not the other way around. At any rate, Hermann von Salsa vanishes from history at this point.

Nothing more was heard of “salsa” for centuries, until the Spanish arrived in Mexico.

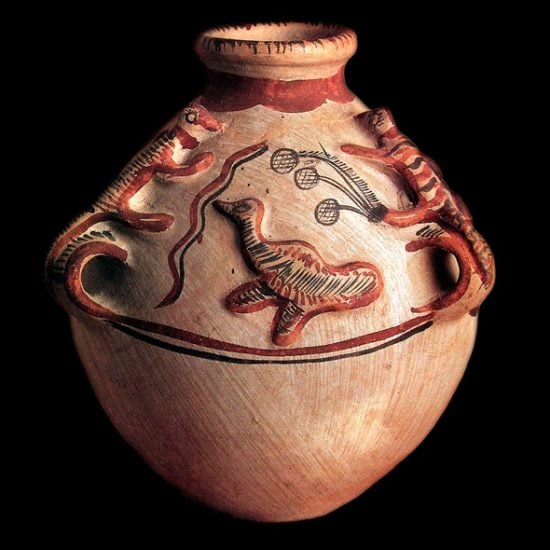

From 1521, the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire incorporated the region into the Spanish Empire. The Spanish found the Aztecs, Mayas, and other inhabitants eating familiar foods (e.g. fish), familiar foods made from unfamiliar ingredients (e.g. breads made from corn, new sorts of beans, turkey), as well as foods that were completely unfamiliar (e.g. cacao, chile peppers, tomatoes, potatoes, avocado). When Alonso de Molina wrote the first dictionary translating Nahuatl to Spanish (Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana y mexicana y castellana, Mexico, 1571), he had to contend with a breadth of terminology describing the sauces used in Aztec cookery, most made with ingredients that were alien to him.

What you find when you collate the recipes for ahuacamolli (guacamole), ayohuachmolli (a green squash seed and chile sauce), chilchomulli (a stew or sauce of tomato and chile), chilmolli (chile sauce), chīltlatzoyōntli (chiles and onions cooked in fat), texxochilli (sauce made from dried chiles and tomato), and tomachilli (a sauce of tomato and chile) et al is that there were, sort of, two different types of sauces. Both were often made with tomatoes, and both were just about always made with chiles; but one was ground up in a mortar (the mollis) and one was not (which the Spanish started to call salsa).

To complicate matters, though Molina’s dictionary sometimes differentiates between tomatillos (calling them tomatl) and yellow and red tomatoes (calling them xitomatl), sometimes he just calls them all tomatl. (To be clear, the Aztecs had lots of different words for different sorts of tomatoes; it is in the relating that they get mixed up). To the Aztecs, these constructions were descriptive: the molli ending on a sauce name just meant that it was ground (or, sometimes confusingly, had elements that were ground, like clemole, a stew where the chiles are ground, but most other ingredients are in chunks). But the Spanish drew lines of demarcation that set the foundations for how we view Mexican sauces today, even if it ultimately had little effect on how Mexicans view salsa.

The Mexican “salsas” were lumped together with all the other salsas from Europe — be they Spanish, French, English or Italian. These were the Mexican sauces that made sense to the colonizers, the ones that were enclosable, commodifiable — salsa, of course, just means sauce in Spanish. But it was only certain Mexican sauces that they called salsas. Similar to the foods that became “curry” when the British East India company drew a circle around Indian food – though unlike Chicken Tikka Masala, salsa didn’t quite have to be invented. In 19th century cookbooks, the salsas and the moles were kept fastidiously separate. But what was referred to as “salsas” depended on the cookbook author’s agenda.

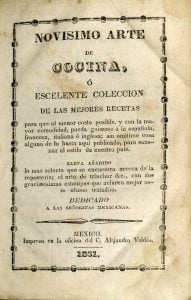

Notes on a few cookbooks of Mexican cuisine.

- The first Mexican cookbook, Novisimo Arte de Cocina (1831) has recipes for tomatillo salsa, tomato salsa (both of which include “pimienta,” not chiles, which is telling — this ambiguity could mean black pepper or chiles depending on which side you were on), as well salsa cruda verde (a parsley sauce, not tomatillo and chile), and a few dozen other European sauces.

- The much reprinted (usually in Paris) Eurocentric Mexican cookery Nuevo Cocinero Mejicano en Forma de Diccionario first published in 1845, includes a long section of sauces including bechamel; salsa Inglesa (with parsley, vinegar, onion, and egg yolks); Breton, Turkish, Macedonian, mayonnaise, and Provençal sauces; and also salsa de xitomate, chile verde y aguacate (avocado), salsa de chiles poblanos, salsa de xitomates con chiles poblanos, salsa de chiles pasilla con vinagre, salsa de xitomate crudo (a sort of pico de gallo), salsa de tomate (tomatillo and green chiles), and a garlic cumin salsa with chiles.

- 1882’s Cocinera Poblana, a cookbook with more nationalist leanings, lists over 50 sauces, all European (Hollandaise, Tomato and Chile sauce Italian style, Provençal, Sauce Robert, etc.), and keeps the moles safely separate in “Cocina Mexicana” — which occupies volume II of the cookbook. Though the moles were not too proud to borrow the occasional European ingredient, as evidenced by the section of almond moles (though the most transformative European addition to Mexican food was animal fat). Here we find moles of tomato and chile serranos and tomato and chile mulatos that might have been salsas elsewhere, had they been chunkier and not under siege from abroad. On a side note: these are similar to the very simple mole that is popular in New Mexico and usually called chile sauce — red or green — and made with liquid, ground chile and spices. They were also likely similar to what is now called salsa roja.

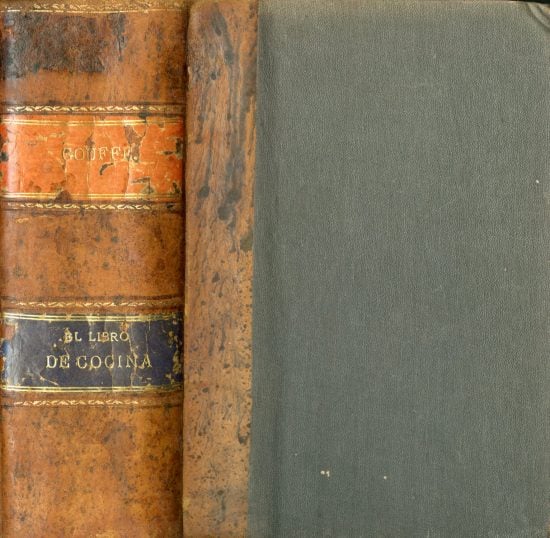

- In 1893, the last of the important European cookeries was published in Mexico — a translation of Jules Gouffé’s popular Livre de Cuisine with a long supplement (not always included) on the cuisine of Mexico. Like the Nuevo Cocinero, it mixes up Mexican salsas with European sauces, and in an extreme rhetorical move, puts all of the moles in the guajolote (turkey) section. But this was the last shot fired — the most popular Mexican cookbook in the first half of the 20th century, an updated version of La Cocinera Poblana o el Libro de las Familias, has a short section of salsas, all European, and the rest of the sauces are listed as mole, or as became common, guisados — a sort of stew of meat or other ingredients and a thick sauce that can be put right on a tortilla.

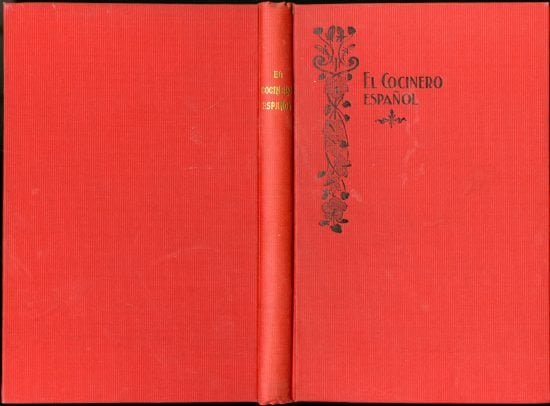

- In 1898, the first Spanish-language cookbook was published in the U.S., Encarnacion Pinedo’s El Cocinero Español. She has a recipe for New Mexican style sauce that she calls salsa de chile colorado as well as a few other recognizable “salsas” including chile verde. Pinedo is an interesting case because she specifically traced her cookery back to Europe, yet used a host of Mexican ingredients — and her family had been living in California since the late 18th century. This set of factors makes analysis of her place in salsa history fraught, but provides insight into how food ideas are transmitted.

By the time Ortega launched the first canned “salsa” in 1908, marketed as “Tru Salsa”, salsa (other than the rare outliers like red chile salsa made with pulque called salsa borracha) was more or less firmly how cookbooks referred to European sauces in Mexico, so it makes a sort of sense that it would be what Americans called Mexican sauces in America. In America moles were largely unknown and when they were recognized, it was those alien sauces with chocolate in them, even though only a small number of moles actually have cacao as an ingredient – most famously mole poblano, somewhat ironically (or extremely aptly; or both), a post-colonial dish made with pre-columbian ingredients. Mole poblano went through its own congruent battles: Spanish stories of how it was invented by nuns at the convent of Santa Rosa during the 16th century for a bishop’s visit began to percolate in the early 20th century – their first time in print was the 1930s – and did battle with pre-columbian genesis stories. Though there has never been a resolution to its origins, it is most likely that it was created shortly after Aztec rules against using cacao in non religious cookery fell by the wayside, and not by the Spanish.

Salsa had been colonized, chased out of town, but mole had made its narrow escape. Since then many salsas have been repatriated – especially since mid century when cookbook authors like Josefina Velazquez de Leon collected recipes for a pan-Mexican cuisine. Salsas, like so many sauces turned condiments, also made an escape – out of cookbooks and into the wild as condiments to be used in whatever fashion people and their stomachs willed. Maybe the Spanish even did Mexico a favor by chasing salsa out of dusty books and into the world, even if their motives were paternalistic and generally lousy — but we are on the trail of salsa as it fled North from the depredations of the Spanish conquerors. As I’ve written about condiments and democracy before, I would be remiss if I didn’t add that these attempts to corral Mexican sauces were aided the natural democratization of Mexican cuisine. As sauces moved from rigidly hierarchical societies like the Aztec and Spanish monarchies into a more democratic Mexico, and then to the United States, it was natural for them to be co-opted and turned into condiments that were controlled by the many instead of royalty, chefs and cookbook authors.

[I don’t want to sound crazy, but around this time, in 1917, The Nevada Railroad Commission published their 11th annual report which contains a series of pages filled with numbers that google now recognizes as the word “salsa” making me wonder where else salsa ran off to, what strange nooks and crannies did salsa, so recently colonized, colonize?]

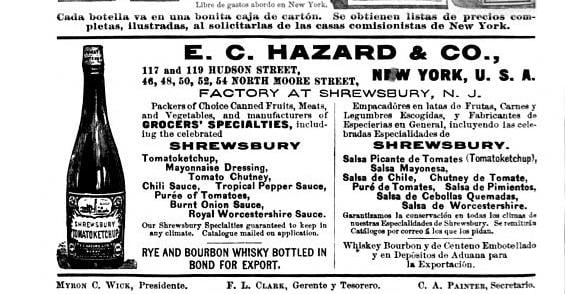

The 1908 Ortega salsa and a few other early manufactured interpretations of salsas and chile sauces intended to exclusively function as condiments made an impact but failed to take off nationally – maybe it was salsa in a can that got in the way? Or maybe it just wasn’t ready to compete with the final and most successful formulation of Heinz Ketchup which was launched in 1906. Local producers made chile and hot sauces, but that was about it. It wasn’t until 1947 and the introduction of Pace Picante sauce in San Antonio, that salsa took the form that we are most familiar with today. As Mexican sauces had been interpreted by Spanish eyes into forms they were comfortable with, so Pace interpreted it again, through American eyes, adding tomato puré and vinegar, making it a mix of hot sauce and something more like the “salsa de gitomate con chille à la italiana” from Gouffé’s El Libro de Cocina or just more like ketchup with tomato chunks and chiles.

“Taco Sauce”, a bastardized sort of mole that is used to “flavor” American tacos, came around at the same time (Lindy’s Taco Sauce was copyrighted in 1947). Pace’s popularity grew and attracted competitors, but with very few exceptions, and somewhat remarkably given the wide range of source material, they copied the general consistency and ingredients of Pace. By the 1980s, American’s palates, slowly expanded by immigrant cuisines from China, Italy and elsewhere, were sufficiently broad that Pace branched out from their regular recipe adding hot and mild varieties and later introduced thick and chunky. In a much publicized sea change, salsa outsold ketchup at some point in the 1990s to become condiment king of America – and even if it’s a lot more expensive than ketchup, and it’s not exactly apples to apples, that’s still a whole lot of salsa. Did Pace put the finishing touches on the project of stealing salsa that the Spanish had begun centuries ago? Or did they save it and turn it forever into a beloved if simplistic condiment, free to be used in a hundred different ways? Does it even bear any relationship to what salsa once was? If you took Pace back to the Aztec market that Bernardino de Sahagun described in The Florentine Codex (late 16th c.) where they sold tomatoes and tomatillos and an array of chiles and made-up sauces, would they have recognized it? Would they have warmed up a batch to cook you in?

I dunno, but somehow an Aztec sauce was embraced, and broken, and chased out of Mexico by the Spanish, landed in Texas, got embraced and ketchuped by Americans, and became one of the most popular condiments in the world.

What I await, with terror and hope and hunger, is Pace Mole ™ and somewhere, I know, Hermann von Salsa waits with me.

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

MORE POSTS BY TOM NEALON: Salsa Mahonesa and the Seven Years War, Golden Apples, Crimson Stew, Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc., and his De Condimentis series (Fish Sauce | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy) — are among the most popular we’ve ever published here at HILOBROW.