Stuffed (11)

By:

April 19, 2016

One in a popular series of posts by Tom Nealon, author of the forthcoming Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste (British Library Publishing, September 2016). STUFFED is inspired by Nealon’s collection of rare cookbooks, which he sells — among other things — via Pazzo Books.

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

Modernist cuisine, or whatever you want to call current haute cuisine of the molecular variety, is, like all food for the elite, engaged in a complicated game of subterfuge. The current aim, insofar as it can be reduced and generalized, seems to be for the food to look like itself only better and more photogenic. Leeks, even if they’ve been reduced to a foam and reconstituted, should look like they made a rapid, but gentle, journey from farm to saute pan to table; the pork belly, even if just freshly emerged from a centrifuge, like it was humanely killed after a quick frolic in the barnyard, possibly by a quick thrust of a unicorn horn or a gentle smothering in kale. A sort of culinary naturalism, aided by high tech. Centuries ago, however, illusions were a little more elaborate.

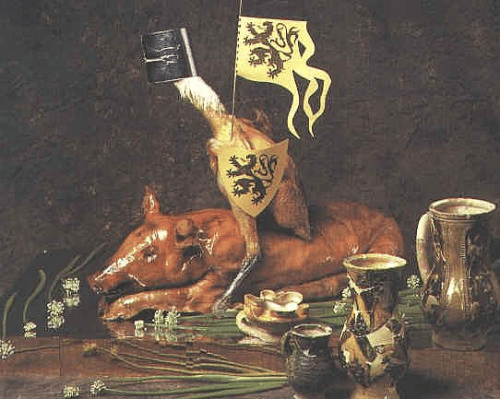

Entremets, in the original sense of something in between courses that led from the roast to the dessert, were a fixture on the high table from the middle ages until the Industrial Revolution. They took many forms – some borrowed from earlier cultures, like the illusion foods of the Romans who would, for example, stuff a hog with thrushes, paunches, fig-peckers, eggs, oysters and periwinkles — many invented for this purpose. Delicate meat aspics, peacocks skinned and dressed back in their feathers, fruit doppelgangers made from sugar, meat or marzipan, and over the top hallucinations like the half chicken half pig cockatrice or the Coqz Heaumez, the helmeted pig riding cock, appeared alongside non-food related intermezzos, entertainments meant to bemuse and distract while the next courses were prepared.

What made the elaborate entremets of the middle ages possible was the vast income disparities between lord and peasant. Because the gulf between the haves and have nots was so very large, labor was ludicrously cheap — having the help boil bones all day for aspics and puddings, skin peacocks, sew together small farm animals and perform the funny bits from morality plays every time you had a hankering to have some friends over for dinner was no problem at all. They were ostentatious, obnoxious, elitist and, like the pyramids, or the Great Wall of China or other massive projects that relied on the confluence of the hugely rich and the abysmally poor, inspiring and sublime and terrible. Like today where Bushwick barbecues feature pork shoulders and oxtails, often the food of the poor was repurposed in elaborate presentations so ironic that there ought to be another word for it. Aspic, once a clever method for people staving off protein deficiency to wring every last bit of nourishment from animal bones, was turned into glittering illusions. One mid 16th century German recipe describes a two-tone carp aspic (what the French call poisson en gelée — a close relative of gefilte fish) poured twice (for the two different color aspics, brown and white) into wagon wheel moulds with trout sticking out of them that are then affixed to a (presumably miniature) wagon as an attractive centerpiece. In a world of scarcity, these illusion foods mocked food shortages , mocked and angered the poor, and inspired the thin slice of people in between to reach for something more.

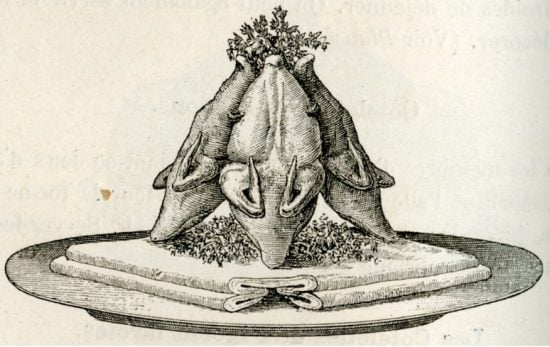

The result of all of this anger and aspiring was the Renaissance and Enlightenment as a middle class formed and, eventually, monarchies were overthrown, usually violently. Along the way were scattered fancy but approachable recipes like Menon’s pumpkin (1755), which is hollowed out to hold pumpkin soup and then glazed with saffron tinged meringue so that it resembles a… pumpkin; or Grimod de la Reyniere’s famous rôti sans pareil, 17 birds stuffed one inside the next with an olive stuffed with an anchovy stuffed with a caper at the center written while the French Revolution still struggled to resolve itself. You can mock the poor and you can starve the poor, but mocking them with their starvation proved a step too far. The cookery that formed in the wake of all this excess, though, provided the foundation for modern cookery and most of what we think of as haute cuisine. Beginning with La Varenne’s Cuisinier François (1651), fancy cookery started to become more about science and artistry than manpower. A modular and exquisite sort of upper class cookery emerged that was just as elaborate and almost as elitist as its predecessor, but reachable by anyone with some money, not just landowners with armies of servants.

La Varenne’s cookery led, with many twists and turns, to the Western haute cuisine that held thrall from the mid 19th century until very recently. Somewhere in between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the bursting of the tech bubble, a new sort of high end cuisine took hold. It incorporated elements of past cuisines — the showy minimalism of nouvelle cuisine (which it was sneakily replacing), the POW of cuisine classique, the playfulness of medieval illusion foods, all mixed together with the latest in scientific cookery and obsession with local ingredients. The science, of course, is nothing entirely new — every age has had its infatuation with new cooking technologies, whether it is the fork, the plate, enlightenment chemistry, chafing dishes, refrigeration, or microwaves. But this was something on a different scale. In addition to new cooking devices like sous-vide cookers, this cuisine was using actual scientific equipment — equipment that was so prohibitively expensive that it is as impossible to replicate in a normal home as 14th century royal feasts once were.

But are they really connected? Yes. While rich people food often has an effect on what the rest of us eat, the effect was especially pronounced in the middle ages when royal cuisine mirrored and prefigured and caused upheavals in society by pissing off the peasantry and filling the middle classes with gluttonous yearnings. Income and diet inequality grew throughout the middle ages, setting off a series of increasingly common and widespread peasant revolts beginning in the 14th century. By the 17th century, the French cleverly separated royal and bourgeois cuisine into completely separate realms and they more or less stayed that way. No one suggested that you should eat haute cuisine all the time and, really, few suggested that you should eat it at all. It existed in a realm that most people didn’t really think about outside of the movies or overheard conversations between douchebag stockbrokers. Which made it no different from haute cuisine for the last hundred plus years — regular folks didn’t spend much time thinking about giant Carême cakes in 1850 either. But what has happened recently, and similar in food history only to medieval illusion foods, is that a confluence of playfulness, huge income disparities, genuine novelty, and the explosion of food television has caused haute cuisine to seep into popular culture with some interesting results. Since 1980 the number of median incomes that the 1% make has almost tripled — in 1980 the 1% made 12 and a half times what an average person made, but by the time of the housing bubble in 2006, it was 36 times. Since then it has worsened.

Molecular cuisine is less illusion than dream or simulacrum, but in a world inured to illusion and preferring delusion, it serves much the same purpose. New techniques allow flavors and textures to divorce and recombine in novel ways — weird foams allow flavors to wander textureless, and foods that we were sure were soft are just as likely to appear brittle, and vice versa, dishes are deconstructed and turned on their heads (like this bagel with cream cheese and lox) causing diners to rethink their assumptions about food while being occasionally horrified. Many of the ideas and values of this new(ish) cuisine have drifted into normal discourse — umami and sous-vide and deconstructed bagel recipes on chefthisup.com testify to that.

On the plus side, some of what used to be high-end machinery is now affordable for normal people (e.g. you can buy a good sous-vide machine for less than $200 — centrifuges have had less of a price drop) and the mania for local food has had good (though also questionable and annoying) consequences. More importantly, a taste for experimentation, fun, and a broader reach for interesting ingredients has started to permeate contemporary cookery. Of course there are some bumps when trickling down rich people food to the masses, as this recent article pointing out that most “farm to table” and “locally grown” claims on Florida restaurant menus are bogus. Did members of the upwelling classes sometimes use a squash to make Menon’s illusion pumpkin soup? Did they occasionally use a sequence of differently sized chickens in the middle of Grimod’s rôti instead of a chicken stuffed with a duck stuffed with a guinea fowl stuffed with a teal stuffed with a woodcock? Sure. So it’s a process. Hopefully.

Of course at the dressing up peacocks and aspic wagon wheel end of the spectrum there will always be douchbaggery: Nathan Myhrvold’s Modernist Cuisine is a pointlessly long $625 doorstop — though it does have nice pictures — and modernist cuisine for the $200+ crowd routinely jumps the shark. At those funny Brazilian joints they have stop and go cards that diners can deploy to stop and start the flow of meats onto their plates. Some of these modernist places that feature tasting menus — essentially endless processions of entremets — should have question mark cards so that traumatized customers can pause the madness to say “Hey, what course are we on? WHAT THE FUCK IS HAPPENING? WHAT AM I EATING?” But that’s missing the point. Sure, it’s plenty aggravating, but that’s the point. We get aggravated, we get ideas, we eat more interesting food, and then, god willing, it’s off with their heads.

MORE POSTS BY TOM NEALON: Salsa Mahonesa and the Seven Years War, Golden Apples, Crimson Stew, Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc., and his De Condimentis series (Fish Sauce | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy) — are among the most popular we’ve ever published here at HILOBROW.