THIS: On and Off the Trail

By:

April 11, 2016

Reflections on the April 6, 2016 release of a milestone graphic narrative and demise of a country-music icon

Merle Haggard died on the same day the Black Panther was reborn. Only one was a fictional character, but both are layered in myth and have represented many things beyond their control. This sheer pop-culture coincidence could, to a believer in the universe’s associative design, be seen to signify the death and resurrection of two cultural legacies with roots in the common decade in which both singer and superhero were invented.

Country musician Haggard’s authenticity got associated with authority; his dim view of the counterculture, though somewhat qualified and countered years later (he ended up singing against the Iraq War and defending the Dixie Chicks), made him a symbol of establishment values; the Black Panther was created mere months before the revolutionary political movement of same name in 1966, and was a symbol of black empowerment (and implicit reordering of the social status quo) from the start. And yet Haggard had wanted to follow up his reactionary hit “Okie From Muskogee” with the sincere anti-racist anthem “Irma Jackson” as a single (though he did back down to his record company’s objections, perhaps the only, and worst, time he ever let someone tell him what to do), and the Panther, king of a fictional high-tech yet nature-respecting utopia in Africa, in addition to being a rebuke to the myth of European superiority, has elements of the model-minority persona that African-Americans perceived in self-congratulatory white pop-aganda of the same period like the interracial-marriage melodrama Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.

To be acceptable, a black man in a white household had to be a paragon, and the Panther’s location in an idyllic kingdom on another continent displaced and minimized America’s contemporaneous inequities. On the other hand, this was also the decade of colonial overthrow in Africa (and not seldom overturn, by dictators aligned as often as not with the U.S.), so the Panther’s premise was an affirmation of black self-rule that was hard to come by anywhere else in majority pop of the era. Figures of white enthusiasm were of course much less obligated to prove themselves, and figures like Haggard could seem like the normative, complacent patriarch. Though many of his hits dealt mournfully with his own history as a frequent offender and convict in his youth — an honest emblem of white criminality in contrast to the rampaging stereotype of social dissidents and communities of color. He may not have been a rebel, but he became respected as an “outlaw” (bucking left and right orthodoxies in turn); T’Challa of Wakanda was a revolutionary symbol, but one who held an absolute authority.

America has always romanticized the rugged individual and held nostalgia for a fairytale feudal state. The contradictions used to balance each other out; now they are cracking the country in pieces like never before. The America of traditional values like those likely held by many 1960s Haggard fans is fighting to survive in the Trump movement, and the America of experiment and possibility signified by insurgent ’60s pop like the Black Panther seems ready to assume a second life in the Sanders campaign — but the new Black Panther comic, the tale of a king published in an election year, is about the competition of general and self-interest that raises unsettled questions about whether any rights-based civil society can long endure.

The thinker to consider these questions in a theoretical world is someone who has spent many years examining them in the actual one — Ta-Nehisi Coates, visionary commentator on America’s racial divide and distortions of law. Crossovers from other media and separate fields — TV and movie writers, novelists, playwrights, academics — can sometimes be stunt-casting (the jettisoning of the popular but non-famous Christopher Priest for an overrated run by Reginald Hudlin on this very comic is one gloomy example), and signing up Coates, a nonfiction writer, is one of the biggest dares of all. It’s also one of the all-time most fruitful. Coates is a reluctant sage who enlightens many but himself writes to learn, and the newness of this latest challenge makes him open to where the storytelling can take him (and lets him take it in novel directions). The art of oratory articulates hopes that spring eternal and describes places that aren’t yet there. This is the insight that an essayist brings to the intersection of fantasy and human truth that the new Black Panther achieves.

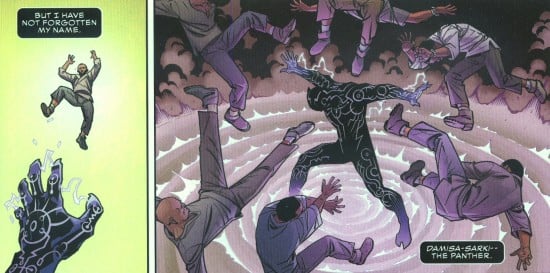

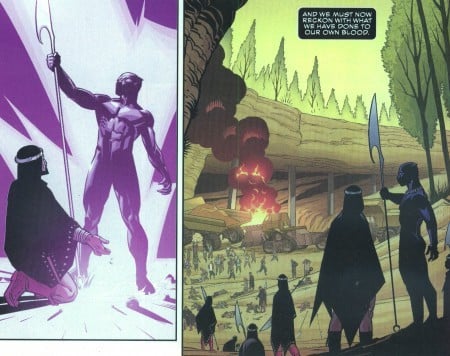

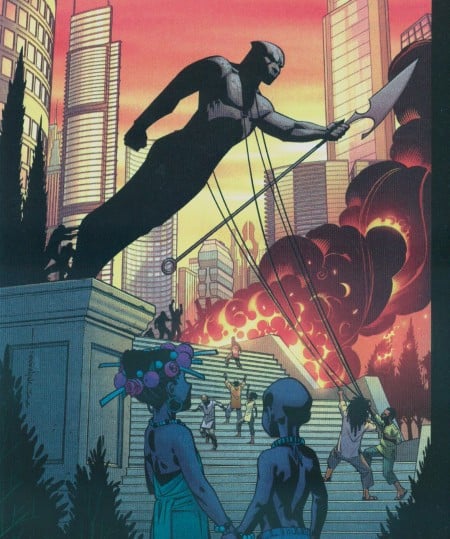

The best treatments of T’Challa, like those of Atlantean monarch Namor (tantalizingly seen for one panel in Coates’ first issue), draw not on his superheroic profile but on the intrigues of his society and station. As we join Coates’ story, Wakanda is coming apart, with an insurgent group appealing to a population traumatized and agitated by recent natural disasters and civic disruptions. T’Challa is a bit of a supporting character in this first chapter, while everything that happens swirls around his once-absolute authority and his perceived failings. This book is also among the best-ever treatments of the character in that the writers who understand him have always recognized his ambivalence about his position; not noblesse oblige but true psychic burden over the ethical contradictions of holding onto rule while empowering your people. In this first issue the tension is tactile and the sense of consequence — in bloody civil unrest, in impending executions — is harrowing and immediate.

And the possible heights are exhilarating — the closeness of his collaboration with artist Brian Stelfreeze is something Coates has been vocal about, and this is true to the spirit of the Lee & Kirby combination that first created the character. Stelfreeze’s conception of Wakanda’s futuristic-is-now architecture, and his portrayal of the intersections between modern structures and natural space, build upon and rival Kirby’s concepts of arcadian urbanism (Wakanda, Attilan, New Genesis); Stelfreeze’s incorporation of traditional and technological motifs — circuitry that looks like tribal markings, ritualistic yet fashionable garb, lyrical and fearsome machinery — fit well in the lineage of Kirby’s trademark Aztec-Kabbalistic-transistor designs. Manny Mederos’ framing design makes us feel like we’re in a lavish fantasy news magazine, picking up on Stelfreeze’s fluid yet chiseled style and inspired sense of pattern electrically. Laura Martin’s colors covey a connoisseurial lushness and a vivid, at-once highly fanciful and deeply familiar sense of place.

The kind of people who would populate such a place are crafted in Coates’ sculptural words. Incantatory enumerations (“Villainy rules. Justice is a slave.”); self-invoking mystical soliloquies (“My name is my nature,” the Panther says, “I track not the body, but the soul within.”); poetic associations (the multi-tribal palace guard are “the blood-alloy of Wakanda itself”); moral commandments (“It is not enough to be the sword, you must be the intelligence behind it.”); transcendent, narrative conceptions of consciousness (“They are going to kill us, so I shall speak as my dead self, which is my best self…”) — the credible culture built one speech-pattern and personal code at a time is among the most imaginative yet real-feeling I’ve ever seen in mainstream comics.

The prevalence and centrality of dimensional and self-determined female characters (the palace guard; T’Challa’s step-mother; assorted allies and antagonists and in-between) is refreshing for the medium, and true to African experience (after all, the real-life super-leaders of today are figures like Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, and Benin’s ahosi were a historical women warrior-class).

In our own world, customs have to die for new ways of being to rise; individuals have no choice but to give way to those who come after them. In the lands of the mind, ideas get to revive and go forward. The 2016 Black Panther, a parable of nations falling and social structures on shaky ground, is a dream of whether wise decisions can withstand the pain of being born into the real.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2024 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE