The Perfect Flâneur

By:

February 14, 2016

Originally published in issue 12 of the British journal The New Escapologist (Winter 2016, ed. by HiLobrow contributor Rob Wringham.)

Flânerie is not aimless idle behavior; to the contrary, it is idle behavior with an aim! Whether roaming a city’s streets without a fixed destination, or simply loitering in an ostentatious manner, the flâneur practices a guerrilla street theater. How so? An idler wheel in the metropolitan mechanism, the flâneur’s contrary mode of ambulation serves to rebuke all those urbanites hustling and bustling purposefully from A to B. By doing nothing, that is, the flâneur reminds us that getting things done is not life’s sole aim.

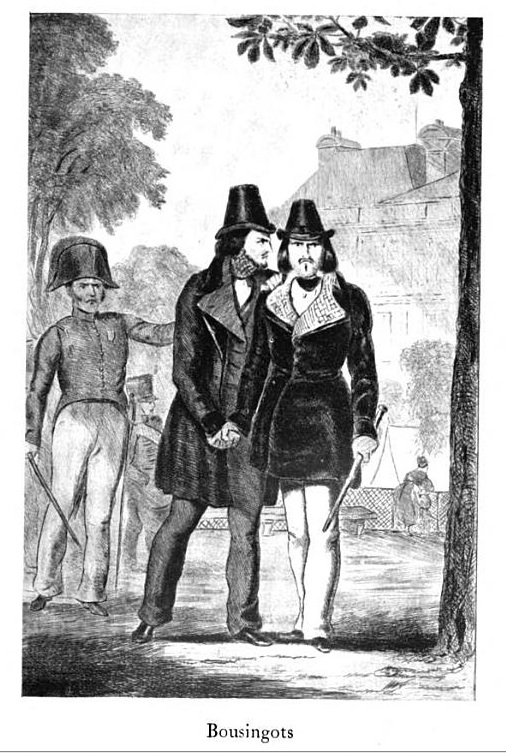

In its street-theater form, flânerie first emerged in Paris, during the reign of the “bourgeois king” Louis-Philippe in the 1830s–1840s, among a proto-Situationist cohort of French authors and poets. Discovering that their leisurely, mindful means of artistic production conflicted with the relentless modes and rhythms of France’s newly industrialized literary market, Théophile Gautier, Petrus Borel, Philothée O’Neddy, Gérard de Nerval, and others protested the ascendant bourgeois cult of efficiency and utility. Ironically adopting the pejorative term bouzingo (which means: good-for-nothing, shit-heel), Gautier, et al., articulated a counter-doctrine of inefficiency and uselessness — of which their flânerie was merely the most performative, emblematic expression.

“Nothing is truly beautiful,” Gautier would proclaim in the influential preface to his 1835 novel Mademoiselle de Maupin, “unless it is useless.” According to Luc Sante, writing for HiLobrow, the Bouzingos “flirted with nudism, smoked hashish, dressed extravagantly, waved daggers, drank from skulls, lived every minute in a state of heightened artifice, as if they were onstage.” Absent the socio-political context of France under Louis-Philippe, all this sort of thing strikes us as shallow, foppish, “aesthetic.” However, if Foucault is correct to propose, in his first major works, that social command in early 19th-century France was no longer simply authoritarian, but had begun to operate through a diffuse network of unspoken rules normalizing certain utilitarian customs, habits, and parameters of thought, then the anti-utilitarian Bouzingos begin to resemble freedom fighters attempting to resist an occupying force.

All of the Bouzingos practiced flânerie, but Nerval took the practice to an extreme. According to a (possibly apocryphal) legend promulgated by Gautier after his friend’s suicide, Nerval went so far as to walk a pet lobster at the end of a blue silk ribbon, among the Palais Royal gardens in Paris. There is, I submit, no mode of ambulation more antithetical to hustling and bustling than this. And it’s worth pointing out, here, that aestheticism — as practiced by an aesthete engagé, like Nerval — is a quixotic attempt to discover and create in everyday life the same opportunities for exaltation that an encounter with a work of art sometimes provides.

However, much like the idler wheel — which, by moving in a direction contrary to the motion of the rest of the machine of which it is a part, performs the vital function of transferring energy from one cog to another — the flâneur’s acts of negation have, since the 1830s, been recuperated by advanced capitalist societies. Today, the rebellious bohemian is everywhere, a shill for increased consumption. This development was anticipated, by the French poet Baudelaire; fortunately, Baudelaire concocted an antidote to the flâneur’s recuperation.

Born in 1821, Baudelaire was an impressionable schoolboy during the Bouzingos’ heyday. Looking back on his life, in his journal, he’d echo Gautier: “To be a useful man always seemed to me something very ugly.” After dropping out of school, Baudelaire squandered his small inheritance in an effort to ape the older men’s dandyism; he and Nerval, both members of Paris’s Hashish Club, became friends. But Baudelaire wasn’t content to ape the pronunciamentos and actions of his idols. A latecomer to the Romantic movement — indeed, one of the pioneers of Post-Romanticism — Baudelaire’s poetry, and his own practice of dandyism and flânerie, demanded to be understood as a meta-commentary on the bourgeois social order’s uncanny knack of absorbing and profiting from his idols’ bohemian rebelliousness.

The Bouzingos’ bohemianism, forged in the crucible of the July Revolution of 1830, which substituted the principle of hereditary right for popular sovereignty, was in important respects anti-democratic. The Bouzingos saw themselves as a self-appointed aristocracy; although penniless, they were wealthy in what Bergson would name la durée: time divorced from productive operations, and devoted instead to contemplation and reverie. De Nerval, for example, was the poet’s assumed aristocratic nom de guerre: Gérard’s real name was a pedestrian one: Labrunie. The Bouzingos’ flânerie was aristocratic, too: Strolling, in an offensively cunctatory fashion, along Paris’s boulevards, the Bouzingos set themselves apart from — and superior to — their fellow pedestrians.

In 1840 another of Baudelaire’s idols, Edgar Allan Poe, published an uncanny fable, “The Man of the Crowd,” a crime-less detective story whose protagonist becomes obsessed with a fiendish figure who, although jostled from pillar to post by blank-faced, zombie-like urbanites, alone manages to remain cool, self-possessed, contemptuous. So Baudelaire admired flânerie, and he could relate to the Bouzingos’ aristocratic desire to resist absorption — like so many cogs, all turning in the same direction — into the urban crowd. However, in his 1863 essay “The Painter of Modern Life,” ostensibly a review of the casual, notational sketches of illustrator Constantin Guys, Baudelaire posits the existence of a flâneur with “an aim loftier than that of a mere flâneur.” For this “perfect flâneur,” Baudelaire suggests, it is “an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement.”

Baudelaire’s perfect flâneur — by “perfect,” he means not flawless, but self-overcoming — is an evolution, a mutation of the Bouzingo. Neither surrendered to the crowd like the zombies in Poe’s story, nor contemptuously aloof from it, the perfect flâneur is both at once. His self-hood isn’t scattered, nor it is zipped up tight; again, it is both at once. His mode of perceiving the city through which he moves isn’t distracted, nor is it self-absorbed; he possesses, instead of these alternatives, a “kaleidoscopic” faculty of perception. If the lowbrow city-dweller is oblivious to everything but the fugitive moment, and the highbrow flâneur is wrapped up in above-it-all contemplations, then Baudelaire’s perfect flâneur is a high-lowbrow attuned to the subtle interplays of the abstract and the everyday.

In his prose-poem “Crowds,” written at the same time as “The Painter of Modern Life,” Baudelaire describes the incomparable ecstasies available to the urban wanderer who can “marry the crowd,” who can — that is — “be both himself and another” rather than remaining egotistically “shut up like a coffin” or losing his sense of self entirely. In “Painter,” Baudelaire suggests that such an extraordinary flâneur is “an I’ with an insatiable appetite for the ‘non-I.'” He is multiple and singular, diffuse and contained, a protean figure.

The perfect flâneur doesn’t hustle and bustle purposefully, nor does she stroll ostentatiously. This high-lowbrow character isn’t a tedious slob, but neither is she an exquisite hipster. A kaleidoscope gifted with consciousness, she saunters and stumbles, musingly, through life like a saint who can see the ideal superimposed on the real. The perfect flâneur is a holy fool, a beautiful loser.

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: TAKING THE MICKEY (series) | KLAATU YOU (series intro) | We Are Iron Man! | And We Lived Beneath the Waves | Is It A Chamber Pot? | I’d Like to Force the World to Sing | The Argonaut Folly | The Perfect Flâneur | The Twentieth Day of January | The Dark Side of Scrabble | The YHWH Virus | Boston (Stalker) Rock | The Sweetest Hangover | The Vibe of Dr. Strange | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM (series intro) | Tyger! Tyger! | Star Wars Semiotics | The Original Stooge | Fake Authenticity | Camp, Kitsch & Cheese | Stallone vs. Eros | The UNCLE Hypothesis | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | The Abductive Method | Semionauts at Work | Origin of the Pogo | The Black Iron Prison | Blue Krishma! | Big Mal Lives! | Schmoozitsu | You Down with VCP? | Calvin Peeing Meme | Daniel Clowes: Against Groovy | The Zine Revolution (series) | Best Adventure Novels (series) | Debating in a Vacuum (notes on the Kirk-Spock-McCoy triad) | Pluperfect PDA (series) | Double Exposure (series) | Fitting Shoes (series) | Cthulhuwatch (series) | Shocking Blocking (series) | Quatschwatch (series)

MORE IDLENESS: THE IDLER’S GLOSSARY | THE WAGE SLAVE’S GLOSSARY | The Perfect Flâneur | The Sweetest Hangover | You Down with VCP? | NEW ESCAPOLOGIST Q&A | H IS FOR HOBO — excerpts from The Idler’s Glossary and The Wage Slave’s Glossary | WAGE SLAVERY — Josh Glenn and Mark Kingwell discuss | IDLENESS — Josh Glenn and Mark Kingwell discuss | IDLER Q&A WITH THE PROGRESSIVE | IDLE IDOL: HENRY MILLER | WATCHING THE DETECTIVES | A SCENE FROM GOODFELLAS.

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE