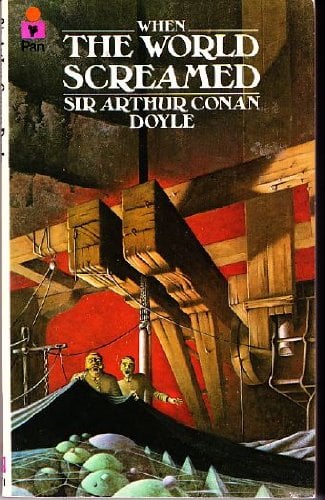

When the World Screamed (8)

By:

November 4, 2015

Arthur Conan Doyle’s novella When the World Screamed was first published in 1928. The fifth and final Professor Challenger adventure, it takes us not outward (e.g., to a South American plateau crawling with dinosaurs), nor inward (e.g., to an airtight chamber, while the Earth passes through a poison belt), but instead downward. Challenger, here described as “a primitive cave-man in a lounge suit,” while also “the greatest brain in Europe,” proposes to drill his way from a tract of land in Sussex (England) eight miles beneath the planet’s epidermis. Why? In order to prove his hypothesis that the world is itself a living organism! Enjoy.

‘Funny-looking stuff,’ said the chief engineer, passing his hand over the nearest section of rock. He held it to the light and showed that it was glistening with a curious slimy scum. ‘There have been shiverings and tremblings down here. I don’t know what we are dealing with. The Professor seems pleased with it, but it’s all new to me.’

‘I am bound to say I’ve seen that wall fairly shake itself,’ said Malone. ‘Last time I was down here we fixed those two cross-beams for your drill, and when we cut into it for the supports it winced at every stroke. The old man’s theory seemed absurd in solid old London town, but down here, eight miles under the surface, I am not so sure about it.’

‘If you saw what was under that tarpaulin you would be even less sure,’ said the engineer. ‘All this lower rock cut like cheese, and when we were through it we came on a new formation like nothing on earth. “Cover it up! Don’t touch it!” said the Professor. So we tarpaulined it according to his instructions, and there it lies.

‘Could we not have a look?’

A frightened expression came over the engineer’s lugubrious countenance.

‘It’s no joke disobeying the Professor,’ said he. ‘He is so damn cunning, too, that you never know what check he has set on you. However, we’ll have a peep and chance it.’

He turned down our reflector lamp so that the light gleamed upon the black tarpaulin. Then he stooped and, seizing a rope which connected up with the corner of the covering, he disclosed half-a-dozen square yards of the surface beneath it.

It was a most extraordinary and terrifying sight. The floor consisted of some greyish material, glazed and shiny, which rose and fell in slow palpitation. The throbs were not direct, but gave the impression of a gentle ripple or rhythm, which ran across the surface. This surface itself was not entirely homogeneous, but beneath it, seen as through ground glass, there were dim whitish patches or vacuoles, which varied constantly in shape and size. We stood all three gazing spell-bound at this extraordinary sight.

‘Does look rather like a skinned animal,’ said Malone, in an awed whisper. ‘The old man may not be so far out with his blessed echinus.’

‘Good Lord!’ I cried. ‘And am I to plunge a harpoon into that beast!’

‘That’s your privilege, my son,’ said Malone, ‘and, sad to relate, unless I give it a miss in baulk, I shall have to be at your side when you do it.’

‘Well, I won’t,’ said the head engineer, with decision.

‘I was never clearer on anything than I am on that. If the old man insists, then I resign my portfolio. Good Lord, look at that!’

The grey surface gave a sudden heave upwards, welling towards us as a wave does when you look down from the bulwarks. Then it subsided and the dim beatings and throbbings continued as before. Barforth lowered the rope and replaced the tarpaulin.

‘Seemed almost as if it knew we were here,’ said he.

‘Why should it swell up towards us like that? I expect the light had some sort of effect upon it.’

‘What am I expected to do now?’ I asked. Mr. Barforth pointed to two beams which lay across the pit just under the stopping place of the lift. There was an interval of about nine inches between them.

‘That was the old man’s idea,’ said he. ‘I think I could have fixed it better, but you might as well try to argue with a mad buffalo. It is easier and safer just to do whatever he says. His idea is that you should use your six-inch bore and fasten it in some way between these supports.’

‘Well, I don’t think there would be much difficulty about that,’ I answered. ‘I’ll take the job over as from to-day.’

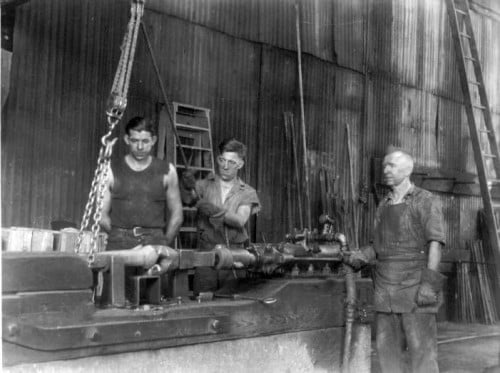

It was, as one might imagine, the strangest experience of my very varied life which has included well-sinking in every continent upon earth. As Professor Challenger was so insistent that the operation should be started from a distance, and as I began to see a good deal of sense in his contention, I had to plan some method of electric control, which was easy enough as the pit was wired from top to bottom. With infinite care my foreman, Peters, and I brought down our lengths of tubing and stacked them on the rocky ledge. Then we raised the stage of the lowest lift so as to give ourselves room. As we proposed to use the percussion system, for it would not do to trust entirely to gravity, we hung our hundred-pound weight over a pulley beneath the lift, and ran our tubes down beneath it with a V-shaped terminal. Finally, the rope which held the weight was secured to the side of the shaft in such a way that an electrical discharge would release it. It was delicate and difficult work done in a more than tropical heat, and with the ever-present feeling that a slip of a foot or the dropping of a tool upon the tarpaulin beneath us might bring about some inconceivable catastrophe. We were awed, too, by our surroundings. Again and again I have seen a strange quiver and shiver pass down the walls, and have even felt a dull throb against my hands as I touched them. Neither Peters nor I were very sorry when we signalled for the last time that we were ready for the surface, and were able to report to Mr. Barforth that Professor Challenger could make his experiment as soon as he chose.

And it was not long that we had to wait. Only three days after my date of completion my notice arrived.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”