Air Bridge (12)

By:

May 16, 2015

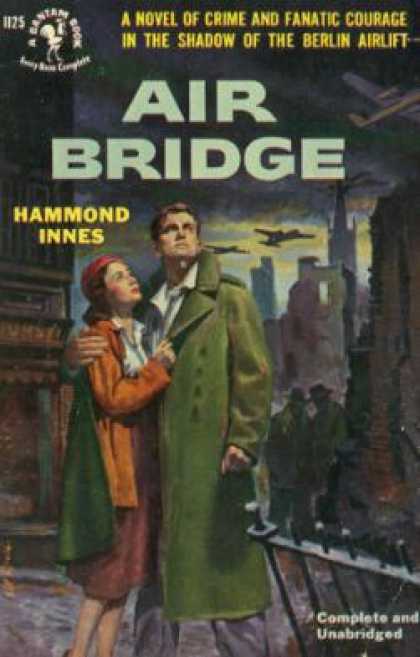

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Hammond Innes’s 1951 espionage thriller/Robinsonade Air Bridge. Set in England during the Berlin blockade and airlift of 1948–49 (during which time the British RAF and other aircrews frustrated the Soviet Union’s attempt to gain practical control of that city), the novel’s protagonist is a mercenary pilot… but is he a traitor? Hammond Innes wrote over 30 adventures, many of them set in hostile natural environments. Enjoy!

He didn’t say anything, ignoring me as I stood oyer him with my hands clenched. “I’ve got to know what happened,” I cried. I caught hold of his shoulder. “Can’t you understand? I can’t go through life thinking myself a murderer. I’ve got to go out there and find him.”

“Find him?” He looked at me as though I were crazy.

“Yes, find him,” I cried. “I believe he’s alive. I’ve got to believe that. If I didn’t believe that —” I moved my hand uncertainly. Couldn’t the man see how I felt about it? “If he’s dead, then I killed him. That’s murder, isn’t it? I’m a murderer then. He’s got to be alive.” I added desperately, “He’s got to be.”

“Better get on with your breakfast.” The gentleness was back in his voice. Damn him! I didn’t want kindness. I wanted something to fight. I wanted action. “When will the plane be ready?” I demanded thickly.

“Sometime tomorrow,” he answered. “Why?”

“That’s too late,” I said. “It’s got to be tonight.”

“Impossible,” he answered. “We’ll barely have got the second motor installed by this evening. Then there’s the tests, refueling, loading the remains of the old Tudor, fixing the —”

“The remains of the old Tudor?” I stared at him. “You mean you’re going through with the plan? You’ll leave Tubby out there another whole day just because —”

“Tubby’s dead,” he said, getting to his feet. “The sooner you realize that, the better. He’s dead and there’s nothing you can do about it.”

“That’s what you want to believe, isn’t it?” I sneered. “You want him dead because if he isn’t dead, he’d give the whole game away.”

“I told you how I feel about Tubby.” His face was white and his tone dangerously quiet. “Now shut up and get on with your breakfast.”

“If Tubby’s dead,” I said, “I’ll do exactly what he would have done if he’d been alive. I’ll go straight to the authori ties —”

“Just what is it you want me to do, Fraser?”

“Fly over there,” I said. “It’s no good a bunch of bored aircrews peering down at those woods from a height of three thousand or more. I want to fly over the area at nought feet. And if that doesn’t produce any result, then I want to land at Hollmind airfield and search those woods on foot.”

He stood looking at me for a moment. “All right,” he said.

“When?” I asked.

“When?” He hesitated. “It’s Tuesday today. We’ll have the second engine installed this evening. Tomorrow I’ll fly down for the C of A. Could be Friday night.”

“Friday night!” I stared at him aghast. “But good God!” I exclaimed. “You’re not going to leave Tubby out there while you get a certificate of airworthiness? You can’t do that. We must go tonight, as soon as we’ve —”

“We’ll go as soon as I’ve got the C of A.” His tone was final.

“But —”

“Don’t be a fool, Neil.” He leaned towards me across the table. “I’m not leaving without a C of A. When I leave it’s going to be for good. I’ll be flying direct to Wunstorf. We’ll call at Hollmind on the way. You must remember, I don’t share your optimism. And now get some breakfast inside you. We’ve got a lot to do.”

“But I must get there tonight,” I insisted. “You don’t understand. I feel —”

“I know very well how you feel,” he said sharply. “Anybody would feel the same if he’d caused the death of a good man like Tubby. But I’m not leaving without a C of A and that’s final.”

“But the C of A might take a week,” I said. “Often it takes longer — two weeks.”

“We’ll have to chance that. Aylmer of B.E.A. has said the Civil Aviation inspectors will rush it through. All right. I’m banking on it taking two days. If it takes longer, that’s just too bad. Now get some breakfast inside you. The sooner we get to work, the sooner you’ll be at Hollmind.”

There was nothing I could do. I got up slowly and fetched my bacon.

“Another thing,” he said as I sat down again. “I’m not landing at Hollmind except in moonlight. If it’s a pitch black night, you’ll have to jump.”

I felt my stomach go cold at the thought of another jump. “Why not go over in daylight?”

“Because it’s Russian territory.”

“You mean because those engines are more important —”

“For God’s sake stop it, Neil.” His voice was suddenly violent. “I’ve made a bargain with you. To land there at night will be dangerous enough. But I’m willing to do it — for the sake of your peace of mind.”

“But not for Tubby?”

He didn’t answer. I knew what he was thinking. He was thinking that if I’d described the scene accurately Tubby couldn’t be alive. But at least he had agreed to look for him now and I held on to that.

The urge to find him drove me to work as I’d never worked the whole time I’d been at Membury. I worked with a concentrated frenzy that narrowed my world down to bolts and petrol unions and the complicated details of electrical wiring. Yet I was conscious at the same time of Saeton’s divergent interest. The clack of his typewriter as he cleared up the company’s business, the phone calls instructing the men he’d picked as a crew to report to R.A.F. Transport Command for priority flights to Buckeburg for Wunstorf — all reminded me that, whatever had happened, his driving purpose was still to get his engines on to the Berlin airlift. And I hated him for his callousness.

It was past midnight when the second engine was in and everything connected up. Saeton left at dawn the next morning. The pipes were all frozen and we got water by breaking the ice on the rainwater butt. Membury was a frozen white world and the sun was hazed in mist so that it was a dull red ball as it came up over the downs. The mist swallowed the Tudor almost immediately. I turned back to the quarters, feeling shut in and wretched.

The next two days were the longest I ever remember. To keep me occupied Saeton had asked me to proceed with the cutting up of the old aircraft into smaller fragments. It occupied my hands. Nothing more. It was an automatic type of work that left my mind free to think. I couldn’t leave the airfield. I couldn’t go anywhere or see anybody. Saeton had been very insistent on that. If I showed my face anywhere and was recognized then he wouldn’t go near Hollmind. It meant I couldn’t even visit the Ellwoods. I was utterly alone and by Friday morning I was peering out of the hangar every few minutes searching the sky, listening for the drone of the returning Tudor.

It was Saturday afternoon that Saeton got in. He had got his C of A. His crew were on their way to Wunstorf. “If it’s clear we’ll go over tonight,” he said. And we got straight on with the work of preparing for our final departure. We tanked up and he insisted on filling the fuselage of the plane with pieces of the old Tudor. He was still intent on going through with his plan. He kept on talking about the airworthiness tests. “The inspectors were pretty puzzled by the engines,” he said. “But I managed to avoid any check on petrol consumption. They know they’re a new design. But they don’t know their value — not yet.” The bastard could think of nothing else.

Dusk was falling as we finished loading. The interior of the hangar was still littered with debris, but Saeton made no attempt to dispose of it. We went back to the quarters. Night had fallen and I had seen the last of Membury. When the moon rose I should be in Germany. I lay in my blankets, barely conscious of the gripping cold, my thoughts clinging almost desperately to my memory of the place.

Saeton called me at ten-thirty. He had made tea and cooked some bacon. As soon as he had finished his meal he went out to the hangar. I lingered over a cigarette, unwilling to leave the warmth of the oil stove, thinking of what lay ahead of me. At length Saeton returned. He was wearing his heavy, fleece-lined flying jacket. “Ready?”

“Yes, I’m ready,” I said and got slowly to my feet.

Outside it was freezing hard, the night crystal clear and filled with stars. Saeton carried the oil stove with him. At the edge of the woods he paused for a moment, staring at the dark bulk of the hangar with the ghostly shape of the plane waiting for us on the apron. “A pity,” he said gruffly. “I’ve got fond of this place.” When we reached the plane he ordered me to get the engines wanned up and went on to the hangar. He was gone about five minutes. When he climbed into the cockpit he was breathing heavily as though he had been running. His clothes smelled faintly of petrol. “Okay. Let’s get going.” He slid into the pilot’s seat and his hand reached for the throttle levers. But instead of taxi-ing out to the runway, he slewed the plane round so that we faced the hangar. The wicket door was still open and a dull light glowed inside. We sat there, the screws turning, the air frame juddering. “What are we waiting for?” I asked.

“Just burning my boats behind me,” he said.

The rectangular opening of the hangar door flared red and I knew then what he had wanted the oil stove for. There was a muffled explosion and flames shot out of the gap. The whole interior of the hangar was ablaze, a roaring inferno which almost drowned the sound of our engines.

“Well, that’s that,” Saeton said. He was grinning like a child who has set fire to something for fun, but his eyes as he looked at me reflected a more desperate mood. Another explosion shook the hangar and flames licked out of the shattered windows at the side. Saeton reached up to the throttle levers, the engines roared and we swung away to the runway end.

A moment later we turned our backs on the hangar and took off into the frosted night. At about a thousand feet Saeton banked slightly for one last glimpse of the field. It was a great dark circle splashed with an orange flare at the far end. As I peered forward across Saeton’s body the hangar seemed to disintegrate into a flaming skeleton of steel. At that distance it looked no bigger than a Guy Fawkes bonfire.

We turned east then, setting course for Germany. I stared at Saeton, seeing the hard inflexible set of the jaw in the light of the instrument panel. There was nothing behind him now. The past to him was forgotten, actively erased by fire. There would be nothing at Membury but molten scraps of metal and the congealed lumps of the engines. As though he knew what I was thinking he said, “While you were sleeping this evening I went over this machine erasing old numbers and stamping in our own.” There was a tight-lipped smile on his face as he said this. He was warning me that there would be no proof, that I would not be believed if I tried to accuse him of flying Harcourt’s plane.

The moon rose as we crossed the Dutch coast, a flattened orange in the east. The Scheldt glimmered below us and then the snaking line of water gave place to frosted earth. “We’re in Germany now,” Saeton shouted, and there was a note of triumph in his voice. In Germany! This was the future for him — the bright, brilliant future to replace the dead past. But for me… I felt cold and alone. There was nothing here for me but the memory of Tubby’s unconscious body slumping through the floor of this very machine — and farther back, tucked away in the dark corners of my mind, the feel of branches tearing at my arm, the sight of the barbed wire and the sense of being hunted.

My brain seemed numb. I couldn’t think and I flew across the British Zone of Germany in a kind of mental vacuum. Then the lights of the airlift planes were below us and we were in the corridor, flying at five thousand feet. Saeton put the nose of the machine down, swinging east to clear the traffic stream and then south-west at less than a thousand with all the ground laid bare in brilliant moon-light, a white world of unending, hedgeless fields and black, impenetrable woods.

We found Hollmind, turned north and in an instant we were over the airfield. Saeton pressed the mouthpiece of his helmet to his lips. “Get aft and open the fuselage door.” His voice crackled in my ears. “You can start shoveling the bits out just as soon as you like. I’ll stooge around to the north of the airfield.” I hesitated and he looked across at me. “You want me to land down there, don’t you?” he said. “Well, this machine’s heavily overloaded. And that runaway hasn’t been used for four years. It’s probably badly broken up by frost and I’m not landing till the weight’s out of the fuselage. Now get aft and kick the load out of her.”

There was no point in arguing with him. I turned and went through the door to the fuselage. The dark bulk of the fuel tanks loomed in front of me. I climbed round them and then I was squeezing my way through the litter of the old Tudor that was piled to the roof. Jagged pieces of metal caught at my flying suit. The fuselage was like an old junk shop and it rattled tinnily. I found the fuselage door, flung it back and a rush of cold air filled the plane. We were flying at about two thousand now, the countryside, sliding below us, clearly mapped in the white moonlight. The wings dipped and quivered as Saeton began to bank the plane. Above me the lights of a plane showed driving south-east towards Berlin with its load of freight; below, the snaking line of a river gleamed for an instant, a road running straight to the north, the black welt of a wood, and then the white weave of plowed earth.

The engines throttled back and I felt the plane check as Saeton applied the air brakes. I caught hold of the nearest piece of metal, dragged it to the wind-filled gap and pushed it out. It went sailing into the void, a gleam of tin twisting and falling through the slip-stream. Soon a whole string of metal was falling away behind us like pieces of silver paper. It was like the phosphorescent gleam of the log line of a ship marking the curve of our flight as we banked.

By the time I’d pitched the last fragment out and the floor of the fuselage was clear, I was sweating hard. I leaned for a moment against the side of the fuselage, panting with the effort. The sweat on me went cold and clammy and I began to shiver. I pulled the door to and went for’ard. “It’s all out now,” I told Saeton.

He nodded. “Good! I’m going down now. I’ll take the perimeter of Hollmind airfield as my mark and fly in widening circles from that. Okay?” He thrust the nose down and the airfield rose to meet us through the windshield. The concrete runways gleamed white, a huge cross. Then we were skimming the field, the starboard wing-tip down as we banked in a right turn. He was taking it clockwise so that I had a clear, easy view of the ground through my side window. “Keep your eyes skinned,” he shouted. “I’ll look after the navigation.”

Round and round we circled, the airfield sliding away till it was lost behind the trees. There was nothing but woods visible through my window, an unending stream of moon-white Christmas trees sliding away below me. My eyes grew dizzy with staring at them, watching their spiky tops and the dark shadows rushing by. The leading edge of the wing seemed to be cutting through them we were so low. Here and there they thinned out, vanishing into patches of plow or the gleam of water. The pattern repeated itself like flaws in a wheel as we droned steadily on that widening circle.

At last the woods had all receded and there was nothing below us but plow. Saeton straightened the plane out then and climbed away to the north. “Well?” he shouted.

But I’d seen nothing — not the glimmer of a light, no fire, no sign of the torn remains of parachute silk — nothing but the fir trees and the open plow. I felt numb and dead inside. Somewhere amongst those woods Tubby had fallen — somewhere deep in the dark shadows his body lay crumpled and broken. I put the mouthpiece of my helmet to my lips. “I’ll have to search those woods on foot,” I said.

“All right,” Saeton’s voice crackled back. “I’ll take you down now. Hold tight. It’s going to be a bumpy touchdown.”

We banked again and the airfield reappeared, showing as a flat clearing in the woods straight ahead of us. Flaps and undercarriage came down as we dropped steeply over the firs. The concrete came to meet us, cracked and covered with the dead stalks of weeds. Then our wheels touched down and the machine was jolting crazily over the uneven surface. We came to rest within a stone’s throw of the woods, the nose of the machine facing west. Saeton followed me out on to the concrete. No light showed in all the huge, flat expanse of the field. Nobody came to challenge us. The place was as derelict and lonely as Membury. Saeton thrust a paper package into my hand. “Bread and cheese,” he said. “And here’s a flask. You may need it.”

“Aren’t you coming with me?” I asked.

He shook his head. “I’m due at Wunstorf at 04:00. Besides what’s the use? We’ve stooged the area for nearly an hour. We’ve seen nothing. To search it thoroughly on foot would take days. It doesn’t look much from the air, but from the ground —” He shook his head again. “Take a look at the size of this airfield. Just to walk straight across it would take you half an hour.”

I stood there, staring at the dark line of the woods, the panic of loneliness creeping up on me. “I won’t be long,” I said. “Surely you can wait an hour for me — two hours perhaps?” The plane was suddenly important to me, my link with people I knew, with people who spoke my own language. Without it, I’d be alone in Germany again — in the Russian Zone.

His hand touched my arm. “You don’t seem to understand, Neil,” he said gently. “You’re not part of my crew — not yet. You’re the pilot of a plane that crashed just north of here. I couldn’t take you on to Wunstorf even if you wanted to come. When you’ve finished your search, make for Berlin. It’s about thirty-five miles to the south-east. You ought to be able to slip across into the British Sector there.”

I stared at him. “You mean you’re leaving me here?” I swallowed quickly, fighting off the sudden panic of fear.

“The arrangement was that I should fly you back to Germany and drop you there. As far as I’m concerned that plan still holds. All that’s different is that I’ve landed you and so saved you a jump.”

Anger burst through my fear, anger at the thought of him not caring a damn about Tubby, thinking only of his plans to fly his engines on the airlift. “You’re not leaving me here, Saeton,” I cried. “But I must know whether he’s alive or dead.”

“We know that already,” he said quietly.

“He’s not dead,” I cried. “He’s only dead in your mind — because you want him dead. He’s not dead, really. He can’t be.”

“Have it your own way.” He shrugged his shoulders and turned away towards the plane.

I caught him by the shoulder and jerked him round.

“All right, he’s dead,” I shouted. “If that’s the way you want it. He’s dead, and you’ve killed him. The one friend you ever had! Well, you’ve killed your one friend — killed him, just as you’d kill anyone who stood between you and what you want.”

He looked me over, measuring my mood, and then his eyes were cold and hard. “I don’t think you’ve quite grasped the situation,” he said slowly. “I didn’t kill Tubby, You killed him.”

“Me?” I laughed. “I suppose it wasn’t your idea that I should pinch Harcourt’s Tudor? I suppose that’s your own machine standing there? You blackmailed me into doing what you wanted. My God! I’ll see the world knows the truth. I don’t care about myself any more. What happened to Tubby has brought me to my senses. You’re mad — that’s what you are. Mad. You’ve lost your reason, all sense of proportion. You don’t care what you do so long as your dreams come true. You’ll sacrifice everything, anyone. Well, I’ll see you don’t get away with it. I’ll tell them the truth when I get back. If you’d got a gun you’d shoot me now, wouldn’t you? Or are you only willing to murder by proxy? Well, you haven’t got a gun and I’ll get back to Berlin somehow. I’ll tell them the truth then. I’ll —”

I paused for breath and he said, “Telling the truth won’t help Tubby now — and it won’t help you either. Try to get the thing clear in your mind, Fraser. Tubby’s dead. And since you killed him, it’s up to you to see that his death is to some purpose.”

“I didn’t kill him,” I shouted. “You killed him.”

He laughed. “Do you think anybody will believe you?”

“They will when they know the facts. When the police have searched Membury, when they have examined that plane and they’ve interrogated —”

“You’ve nothing to support your story,” he said quietly. “The remains of Harcourt’s plane are strewn over the countryside just north of here. Field and Westrop will say that you ordered them to bail out, that the engines had packed up. You yourself will be reporting back from the area of the crash. As for Membury, there’s nothing left of the hangar now except a blackened ruin.”

I felt suddenly exhausted. “So you knew what I’d do. You knew what I was going to do back there at Mem bury. You fooled me into pushing out that load of scrap. By God —”

“Don’t start using your fists,” he cut in sharply. “I may be older than you, but I’m heavier — and tougher.” His feet were straddled and his head was thrust forward, his hands down at his sides ready for me.

I put my hands slowly to my head. “Oh, God!” I felt so weak, so impotent.

“Get some sense into your head before I see you again,” he said. “You can still be in this thing with me — as my partner. It all depends on your attitude when you reach Berlin.”

For answer I turned away and walked slowly towards the woods.

Once I glanced back. Saeton was still standing there, watching me. Then, as I entered the darkness of the trees, I heard the engines roar. Through needle-covered branches I watched the machine turn and taxi to the runway end. And then it went roaring across the airfield, climbing, a single white light, like a faded comet, dwindling into the moonlit night, merging into the stars. Then there was silence and the still shadows of the woods closed round me. I was alone — in the Russian Zone of Germany.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”