Jurgen (7)

By:

April 27, 2015

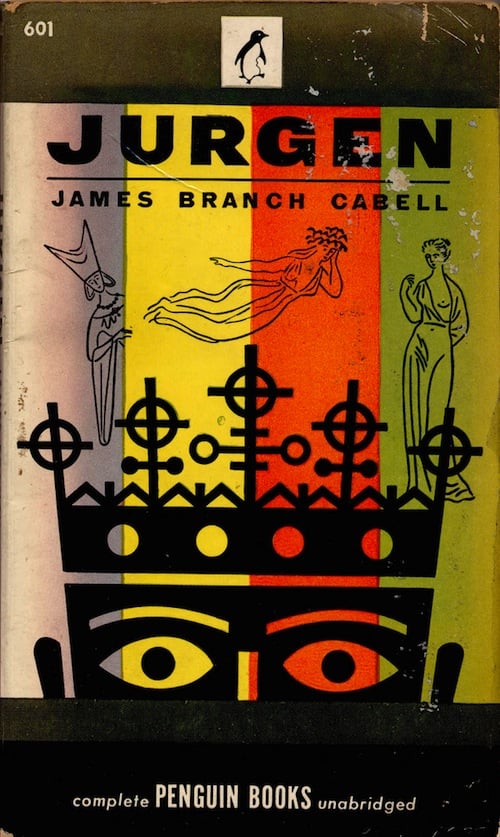

James Branch Cabell’s 1919 ironic fantasy novel Jurgen, A Comedy of Justice, the protagonist of which seduces women everywhere he travels — including into Arthurian legend and Hell itself — is (according to Aleister Crowley) one of the “epoch-making masterpieces of philosophy.” Cabell’s sardonic inversion of romantic fantasy was postmodernist avant la lettre. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Jurgen here at HILOBROW. Enjoy!

Then, having snapped his fingers at that foolish signboard, Jurgen would have turned easterly, toward Bellegarde: but his horse resisted. The pawnbroker decided to accept this as an omen.

“Forward, then!” he said, “in the name of Koshchei.” And thereafter Jurgen permitted the horse to choose its own way.

Thus Jurgen came through a forest, wherein he saw many things not salutary to notice, to a great stone house like a prison, and he sought shelter there. But he could find nobody about the place, until he came to a large hall, newly swept. This was a depressing apartment, in its chill neat emptiness, for it was unfurnished save for a bare deal table, upon which lay a yardstick and a pair of scales. Above this table hung a wicker cage, containing a blue bird, and another wicker cage containing three white pigeons. And in this hall a woman, no longer young, dressed all in blue, and wearing a white towel by way of head-dress was assorting curiously colored cloths.

She had very bright eyes, with wrinkled lids; and now as she looked up at Jurgen her shrunk jaws quivered.

“Ah,” says she, “I have a visitor. Good day to you, in your glittering shirt. It is a garment I seem to recognize.”

“Good day, grandmother! I am looking for my wife, whom I suspect to have been carried off by a devil, poor fellow! Now, having lost my way, I have come to pass the night under your roof.”

“Very good: but few come seeking Mother Sereda of their own accord.”

Then Jurgen knew with whom he talked: and inwardly he was perturbed, for all the Léshy are unreliable in their dealings.

So when he spoke it was very civilly. “And what do you do here, grandmother?”

“I bleach. In time I shall bleach that garment you are wearing. For I take the color out of all things. Thus you see these stuffs here, as they are now. Clotho spun the glowing threads, and Lachesis wove them, as you observe, in curious patterns, very marvelous to see: but when I am done with these stuffs there will be no more color or beauty or strangeness anywhere apparent than in so many dishclouts.”

“Now I perceive,” says Jurgen, “that your power and dominion is more great than any other power which is in the world.”

He made a song of this, in praise of the Léshy and their Days, but more especially in praise of the might of Mother Sereda and of the ruins that have fallen on Wednesday. To Chetverg and Utornik and Subbota he gave their due. Pyatinka and Nedelka also did Jurgen commend for such demolishments as have enregistered their names in the calendar of saints, no less. Ah, but there was none like Mother Sereda: hers was the centre of that power which is the Léshy’s. The others did but nibble at temporal things, like furtive mice: she devastated, like a sandstorm, so that there were many dustheaps where Mother Sereda had passed, but nothing else.

And so on, and so on. The song was no masterpiece, and would not be bettered by repetition. But it was all untrammeled eulogy, and the old woman beat time to it with her lean hands: and her shrunk jaws quivered, and she nodded her white-wrapped head this way and that way, with a rolling motion, and on her thin lips was a very proud and foolish smile.

“That is a good song,” says she; “oh, yes, an excellent song! But you report nothing of my sister Pandelis who controls the day of the Moon.”

“Monday!” says Jurgen: “yes, I neglected Monday, perhaps because she is the oldest of you, but in part because of the exigencies of my rhyme scheme. We must let Pandelis go unhymned. How can I remember everything when I consider the might of Sereda?”

“Why, but,” says Mother Sereda, “Pandelis may not like it, and she may take holiday from her washing some day to have a word with you. However, I repeat, that is an excellent song. And in return for your praise of me, I will tell you that, if your wife has been carried off by a devil, your affair is one which Koshchei alone can remedy. Assuredly, I think it is to him you must go for justice.”

“But how may I come to him, grandmother?”

“Oh, as to that, it does not matter at all which road you follow. All highways, as the saying is, lead roundabout to Koshchei. The one thing needful is not to stand still. This much I will tell you also for your song’s sake, because that was an excellent song, and nobody ever made a song in praise of me before to-day.”

Now Jurgen wondered to see what a simple old creature was this Mother Sereda, who sat before him shaking and grinning and frail as a dead leaf, with her head wrapped in a common kitchen-towel, and whose power was so enormous.

“To think of it,” Jurgen reflected, “that the world I inhabit is ordered by beings who are not one-tenth so clever as I am! I have often suspected as much, and it is decidedly unfair. Now let me see if I cannot make something out of being such a monstrous clever fellow.”

Jurgen said aloud: “I do not wonder that no practising poet ever presumed to make a song of you. You are too majestical. You frighten these rhymesters, who feel themselves to be unworthy of so great a theme. So it remained for you to be appreciated by a pawnbroker, since it is we who handle and observe the treasures of this world after you have handled them.”

“Do you think so?” says she, more pleased than ever. “Now, may be that was the way of it. But I wonder that you who are so fine a poet should ever have become a pawnbroker.”

“Well, and indeed, Mother Sereda, your wonder seems to me another wonder: for I can think of no profession better suited to a retired poet. Why, there is the variety of company! for high and low and even the genteel are pressed sometimes for money: then the plowman slouches into my shop, and the duke sends for me privately. So the people I know, and the bits of their lives I pop into, give me a deal to romance about.”

“Ah, yes, indeed,” says Mother Sereda, wisely, “that well may be the case. But I do not hold with romance, myself.”

“Moreover, sitting in my shop, I wait there quiet-like while tribute comes to me from the ends of earth: everything which men and women have valued anywhere comes sooner or later to me: and jewels and fine knickknacks that were the pride of queens they bring me, and wedding rings, and the baby’s cradle with his little tooth marks on the rim of it, and silver coffin-handles, or it may be an old frying-pan, they bring me, but all comes to Jurgen. So that just to sit there in my dark shop quiet-like, and wonder about the history of my belongings and how they were made mine, is poetry, and is the deep and high and ancient thinking of a god who is dozing among what time has left of a dead world, if you understand me, Mother Sereda.”

“I understand: oho, I understand that which pertains to gods, for a sufficient reason.”

“And then another thing, you do not need any turn for business: people are glad to get whatever you choose to offer, for they would not come otherwise. So you get the shining and rough-edged coins that you can feel the proud king’s head on, with his laurel-wreath like millet seed under your fingers; and you get the flat and greenish coins that are smeared with the titles and the chins and hooked noses of emperors whom nobody remembers or cares about any longer: all just by waiting there quiet-like, and making a favor of it to let customers give you their belongings for a third of what they are worth. And that is easy labor, even for a poet.”

“I understand: I understand all labor.”

“And people treat you a deal more civilly than any real need is, because they are ashamed of trafficking with you at all: I dispute if a poet could get such civility shown him in any other profession. And finally, there is the long idleness between business interviews, with nothing to do save sit there quiet-like and think about the queerness of things in general: and that is always rare employment for a poet, even without the tatters of so many lives and homes heaped up about him like spillikins. So that I would say in all, Mother Sereda, there is certainly no profession better suited to an old poet than the profession of pawnbroking.”

“Certainly, there may be something in what you tell me,” observes Mother Sereda. “I know what the Little Gods are, and I know what work is, but I do not think about these other matters, nor about anything else. I bleach.”

“Ah, and a great deal more I could be saying, too, godmother, but for the fear of wearying you. Nor would I have run on at all about my private affairs were it not that we two are so close related. And kith makes kind, as people say.”

“But how can you and I be kin?”

“Why, heyday, and was I not born upon a Wednesday? That makes you my godmother, does it not?”

“I do not know, dearie, I am sure. Nobody ever cared to claim kin with Mother Sereda before this,” says she, pathetically.

“There can be no doubt, though, on the point, no possible doubt. Sabellius states it plainly. Artemidorus Minor, I grant you, holds the question debatable, but his reasons for doing so are tolerably notorious. Besides, what does all his flimsy sophistry avail against Nicanor’s fine chapter on this very subject? Crushing, I consider it. His logic is final and irrefutable. What can anyone say against Sævius Nicanor? — ah, what indeed?” demanded Jurgen.

And he wondered if there might not have been perchance some such persons somewhere, after all. Their names, in any event, sounded very plausible to Jurgen.

“Ah, dearie, I was never one for learning. It may be as you say.”

“You say ‘it may be’, godmother. That embarrasses me, rather, because I was about to ask for my christening gift, which in the press of other matters you overlooked some forty years back. You will readily conceive that your negligence, however unintentional, might possibly give rise to unkindly criticism: and so I felt I ought to mention it, in common fairness to you.”

“As for that, dearie, ask what you will within the limits of my power. For mine are all the sapphires and turquoises and whatever else in this dusty world is blue; and mine likewise are all the Wednesdays that have ever been or ever will be: and any one of these will I freely give you in return for your fine speeches and your tender heart.”

“Ah, but, godmother, would it be quite just for you to accord me so much more than is granted to other persons?”

“Why, no: but what have I to do with justice? I bleach. Come now, then, do you make a choice! for I can assure you that my sapphires are of the first water, and that many of my oncoming Wednesdays will be well worth seeing.”

“No, godmother, I never greatly cared for jewelry: and the future is but dressing and undressing, and shaving, and eating, and computing percentage, and so on; the future does not interest me now. So I shall modestly content myself with a second-hand Wednesday, with one that you have used and have no further need of: and it will be a Wednesday in the August of such and such a year.”

Mother Sereda agreed to this. “But there are certain rules to be observed,” says she, “for one must have system.”

As she spoke, she undid the towel about her head, and she took a blue comb from her white hair: and she showed Jurgen what was engraved on the comb. It frightened Jurgen, a little: but he nodded assent.

“First, though,” says Mother Sereda, “here is the blue bird. Would you not rather have that, dearie, than your Wednesday? Most people would.”

“Ah, but, godmother,” he replied, “I am Jurgen. No, it is not the blue bird I desire.”

So Mother Sereda took from the wall the wicker cage containing the three white pigeons: and going before him, with small hunched shoulders, and shuffling her feet along the flagstones, she led the way into a courtyard, where, sure enough, they found a tethered he-goat. Of a dark blue color this beast was, and his eyes were wiser than the eyes of a beast.

Then Jurgen set about that which Mother Sereda said was necessary.

Footnotes from Notes on Jurgen (1928), by James P. Cover — with additional comments from the creators of this website; rewritten, in some instances, by HiLoBooks.

* Mother Sereda — Sereda is the Russian word for Wednesday. It means “the middle,” since Wednesday is the middle of the week. Mother Wednesday is a personification of the day after which she is named; and, in Russian folk-lore, is represented as a woman no longer young and wearing a white towel by way of headdress. If Wednesday’s traditional tasks, spinning and bleaching, are not properly done, she is likely to enter the house and do them; but her visit is a thing to be dreaded, and prevented at all costs.

* Léshy — This is Mr. Cabell’s name for all supernatural beings. Léshy is a name given to the gods of Poictesme very much in the same way as Æsir is a name given to the Scandinavian gods. The supernal rulers of Poictesme owe only their names to the léshy of the Russian folk-tales, since these last are wood sprites with iron heads and copper bodies who live in the depths of the forest and kidnap humans.

* Clotho and Lachesis — These were two of the three Classic Fates, whose business was to spin the thread of human destiny.

* Pyatinka — This is Mother Friday of Russian folk-lore. She is a foe to spinning and weaving and does not like to see it done on her day.

* Nedelka — Nedelka is the Russian Mother Sunday. She rules the animal world and can collect her subjects by playing on a magic flute. The accompanying names are, of course, the Russian words for the other days of the week: Pandelis, Monday; Utornik, Tuesday; Chetverg, Thursday; and Subbota, Saturday.

* Sabellius — Sabellius was a Libian priest of the third century and one of the most prominent of the Gnostic leaders. (Sabellians are mentioned elsewhere in the text.)

* Artemidorus — Several ancient writers bore the name of Artemidorus. One was Artemidorus the Geographer, a native of Ephesus, who was the author of travel accounts, and who lived about 100 B.C. Another was the Dream Interpreter, born at Ephesus in the beginning of the second century A.D., who was surnamed “the Daldian,” and who wrote books upon the interpretation of dreams. Still another was a grammarian of the time of Sulla, who is said to be the first editor of the poems of Theocritus. One of these may have been the Artemidorus Minor whom Jurgen pretends to quote.

* Saevius Nicanor — Suetonius, in his Lives of Eminent Grammarians, Chapter V, says “Saevius Nicanor first acquired fame and reputation by his teaching; and, besides, he made commentaries, the greater part of which, however, are said to have been borrowed. He also wrote a satire, in which he informs us that he was a freedman, and had a double cognomen, in the following verses.

Saevius Nicanor Marci libertus negabit,

Saevius Posthumius idem, sed Marcus, docebit.

(What Saevius Nicanor the freedman of Marcus, will deny

The same Saevius, called also Posthumius Marcus, will assert.)

* Such and such a year — The Lineage of Lichfield, page 23, note, makes this year 1256. From the same authority we learn that Jurgen set forth upon his eventful journey on the last day of summer.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”