The Unconquerable (24)

By:

December 11, 2014

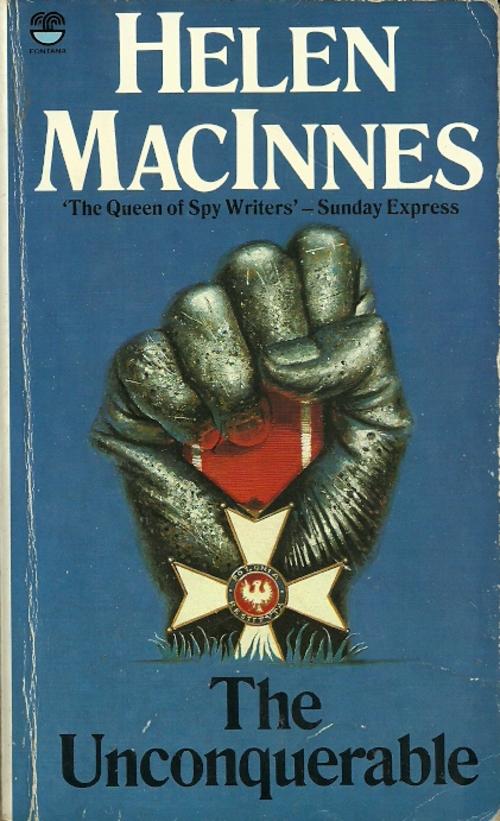

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Helen MacInnes’s 1944 novel The Unconquerable (later reissued as While We Still Live), an espionage adventure that pits an innocent English woman against both Nazis and resistance fighters in occupied Poland. MacInnes, it’s worth noting, was married to a British intelligence agent, which may explain what one hears is the amazing accuracy of her story’s details. Under the editorship of HILOBROW’s Joshua Glenn, the Save the Adventure book club will reissue The Unconquerable as an e-book for the first time ever. Enjoy!

The journey to Korytów had begun. So quickly, so strangely, that for the first five minutes Sheila’s thoughts and hopes and fears had become one huge jumble inside her brain. The rigid control with which she had defended herself in Streit’s office could relax in this car, but she seemed to have lost all power of arranging her thoughts in a logical order. She had had to think too tensely; now she couldn’t think at all. Then a panic seized her; the journey in this high-powered, smooth-running car with the efficient driver at its wheel would be so short; but all she could do now was to keep repeating to herself, “I’ve so much to do. I’ve so much to do.” The more she tried to think how she should try to plan, the more she thought how much there was to plan.

Strangely enough, it was the Germans, the cause of this panic, who now helped her out of it. The car was halted after it left the city. As the driver gave his brief answers Sheila suddenly saw her face reflected by some oblique ray of sunshine in the wind-screen before her. She didn’t look afraid. She didn’t look worried. Her face was quite expressionless. It was like a portrait done by an artist more interested in line and texture than in emotions. Where did I learn all this? she wondered. She stared coldly at the image of quiet assurance. Her mind became as calm as the face she saw in the wind-screen. The car moved on. The image in the glass disappeared. The wide road and wider fields were all she saw ahead now, but this feeling of calm stayed with her.

There was no sense of triumph when she thought of the last hour. She had been partly lucky, partly careful, and partly trying very hard. She had never been so hard-tried in her life. But this journey, this car, the snub to Dittmar gave her no sense of triumph. All she had done was to let herself be entangled more deeply in the Nazi web. When she returned from Korytów Hofmeyer would have to start disentangling her. One Gestapo interview, even a friendly one, was quite enough for one lifetime. She could never manage another. There was a limit to the length of time an amateur juggler could keep his eyes fixed on three balls at once. If Streit had detained her just five minutes more she would have been lost. She might as well admit that now. Heroics only gave you a false idea of yourself. Heroics would only land her firmly trussed in the centre of the web.

But one thing she had accomplished as well as Korytów. Now she could warn Hofmeyer that Dittmar was suspicious, and she could have Olszak warned that Dittmar had a theory about the little-known Kordus. That was at least something. Having allowed herself that crumb of comfort, she began to plan the method of approaching Korytów and the manner of leaving the village. The chief problem was to warn the peasants to leave Korytów without their escape being linked up with her visit. She watched the wide roads and fields and thought of a story with which to safeguard herself. She frowned as she concentrated.

“Terrible country, isn’t it?” the corporal said suddenly, as if in agreement with the frown. “Give me the mountains every time.” His tone was polite, deferential.

“Where do you come from? Bavaria?” she asked. She regretted her question instantly. It always had been one of her weaknesses to respond to pleasantness. Now it was obvious that she was in for a spate of conversation.

“Franconia is my part of the world.”

“Oh.”

“I know it’s flat, too, miss. But the towns and villages are all neat. Look at that!” He waved to a line of houses stretching along the road to form a village. Sheila looked and saw the trampled gardens, the blue-painted walls of the cottages cracked and blackened by smoke, the burnt thatch roofs, the pitted fields.

“Of course,” Treltsch added generously, “there’s been heavy fighting round here.”

“Yes.”

“But just take a place where there hasn’t been fighting, and what do you get?”

“What?”

“Nothing that can equal our towns or villages. We Germans are neat, and we work hard. We are thorough.”

“Yes,” Sheila said. She thought of the people of Korytów who had seemed never to stop working. She thought of the village, rebuilt after the last war. She thought of the German towns and villages which had never known destruction and pillage as Poland had known them for almost two centuries. She looked at the fields. Hardly one of them was empty. Each had its heaps of what seemed rags or old clothing, lying where they had fallen scattered under the machine-gun bullets. Wrecks of carts and skeletons of horses still edged the ditches.

“Glad I don’t live here, anyway. It’s a desolate pigsty.”

Sheila didn’t answer. All she wanted to say was, “It was pleasant enough before you came here. Those who lived here didn’t ask for any change. If you hadn’t come it wouldn’t look either desolate or a pigsty.”

“It just proves everything,” Treltsch said with great conviction. “The Poles are a shiftless lot. It just shows you some people have no right to govern. They just spoil everything.”

“They’ve had a long history of war,” Sheila couldn’t help saying, and then bit her lip. Fortunately for her, her voice was too tired to sound either indignant or sympathetic. Fortunately for her, the man obviously thought she was criticizing the Poles as troublesome neighbours.

The man nodded and then, as if he thought that one word had been too generous to the Poles, he said, “‘History’!” He laughed. “What history? What real history have they ever had?”

Sheila didn’t answer. Treltsch’s school-books would never have mentioned Poland as a nation. The Germans hadn’t even bothered to publish a Baedeker’s guide to Poland.

“What history?” the man insisted. The word was staying with him; his laugh hadn’t chased it away after all. Sheila looked at the youthful face, at the frank brown eyes so intent on the road before them. This man was not setting a trap for her. He was honestly ignorant. He just did not know, he really didn’t believe that anything good existed outside his own country. He was willing, alert, obedient; he was smug, stupid, short-sighted.

Sheila was very casual, almost bored.

“I have heard that the University of Cracow is nearly six hundred years old,” she suggested, keeping purposely silent about the defeat of the Teutonic Knights by the Poles. One of the oldest in Western civilization, she wanted to add; older than Heidelberg. Treltsch’s amazement was obvious. So was his disbelief. What would he have looked like if she had told him that the French Huguenots had appealed to their King for freedom from persecution in the sixteenth century and had cited Poland as an example of religious tolerance? Or if she had told him that the Poles had saved Vienna from the Mohammedan invasion; if they hadn’t there would be mosques and veiled women in Austria, perhaps even in Germany, just as these reminders of Islam remained in Serbia to this day?

“Six hundred years old,” Treltsch said with a laugh. “That’s what the Poles say, I bet. You can’t trust a Pole. You should have seen the way they fought us! They were like demons. They aren’t human. The Führer was right. If we had let them get strong they would have overrun our country. We were wise to attack them first. It was the only way to win.”

“But Germany would never be beaten. No country can beat us. We are invincible.”

“You’re right there, miss.” Treltsch looked happy again; she was speaking of the things he knew.

Then why on earth are you afraid of being attacked? Sheila thought bitterly. If you are invincible, then you need fear no attack. But Treltsch, unaware of the inconsistencies in his logic, was whistling cheerily as the car speeded on.

“Hope you didn’t mind me talking, miss,” he said once. “It’s real good to talk to a German woman again.” And then he was whistling, softly, tunefully once more.

They slowed up once as they passed a cluster of houses. In the lifeless stubble of a long-harvested field a line of men were digging a trench. A group of women and children, closely huddled, were standing near them. The women’s bright kerchiefs matched the autumn leaves at the edge of the field. Facing them were green-uniformed soldiers setting up their machine-guns. Two officers in massive field-coats were smoking cigarettes as they watched the shallow trench grow deeper. At the sign of the village inn a man was hanging. He had been hanging there for some time. Treltsch halted the car beside the wooden table and bench in the inn’s side-garden which bordered the road. Two soldiers patrolling this end of the empty village came forward. Treltsch answered their questions rapidly with the same formula which had brought them through the last patrol. Sheila stared at the calm image of her face in the wind-screen, tried to forget the creaking of the inn’s sign just behind her.

“More sniping?” Treltsch asked as the soldiers relaxed, and nodded over his shoulder in the direction of the field.

“No — they cut him down last night.” The soldier who answered jerked his thumb towards the hanging body. “He got his for food hoarding. Told us lies about what he had and then gave food to a couple of refugees. He’s been up there for four days. Orders. But last night they cut him down. Buried him in a grave, too. But we found him. And he’s back where he belongs.”

“They’ll all soon be where they belong,” the other soldier said with a laugh.

Sheila glanced at her watch. “The light fades quickly now,” she said to Treltsch. “We ought to hurry.”

The soldiers pulled themselves erect, returned the corporal’s salute. The laughing one, serious now, called after the car, “Go carefully. There’s been trouble round here when it gets dark.”

Treltsch was silent for so long that Sheila, looking curiously at the man’s pleasant face, wondered if he felt some pity for the condemned village. She smiled sadly, thinking that perhaps he was beginning to understand why this countryside should be so depressing.

He smiled too. Sympathetically, it seemed to her. And then he said, “You know, miss, I was just thinking: wouldn’t it be funny if one of them was sent to my house?”

He noticed her bewilderment.

“One of these women,” he explained, his eyes on a more difficult part of the road. The trees were thickening now; no longer sparse or isolated, their gay autumn colours formed small masses of shaded reds and yellows. “You see, miss. I’ve got my name down for a Polish worker. My wife always wanted help. Half the day she used to complain about having so much to do. She’s young, you know. So I put my name down on the list. That ought to keep her happy. She can take it easy for a bit and let the Pole do the hard work. It will cost us nothing, not even in food or bedding.”

“But the Pole will eat and sleep, won’t she?”

“Table scraps and a heap of straw out in the shed. That’s almost nothing. It’s what the Poles are used to, miss. Treat swine as swine — that’s what we say in my part of the country.” The man’s voice was casual, friendly. He was simply repeating his creed.

“What happens if — if the woman dies?” she heard her voice ask.

“Oh, they’re strong. They aren’t human. They are like animals. Besides, there’s plenty more. Thirty-five million of them. Yes, when I looked at that bunch of women I thought, ‘You’ll be setting out for Germany, I bet, as soon as the shooting’s over.’ And then I thought, ‘What if I were to see that big, strong, yellow-haired girl scrubbing my doorstep the next time I go home?’ Sounds a bit fanciful, now that I put it in words. But that’s the way things happen. It’s a small world — that’s what I always say.”

“Wouldn’t it be dangerous?” Sheila said in a low voice. “I mean, if a Polish woman, like the yellow-haired girl you mentioned, were separated from her children and sent to work for you might not that be dangerous? For your wife and children?”

Treltsch was serious now. All the amiability left his pleasant face. “Just let any Pole try it. Just let them!” he said, with unexpected depths of anger.

Then his face cleared as he remembered the solution, and his voice was easy once more. “They won’t try it. Not with relations left in Poland, not with their children in our camps. No, miss — don’t you worry about the wife and baby. We’ll look after them. The first thing the Pole will be told will be just what will happen to her family if she tries any tricks. No, don’t you worry, miss.”

Sheila nodded, and pretended to study the woods, now spreading widely over the flat fields.

When Corporal Treltsch spoke again it was to say, “Nearly there, miss. Four miles to go. We’ve made it in good time.”

“Excellent,” Sheila agreed, and studied her watch. “Now, I don’t want you to bring this car into the village. Drop me there, so that I can enter the village on foot.”

“Shall I wait for you there to take you back?”

“I wish you could. But my problem is difficult. I have to bring three Poles back to Warsaw, without their knowing that we are responsible for taking them. They think I am Polish, too.”

“I see, miss. But it’s a long walk back to Warsaw. Perhaps I could pretend to give you a lift? I’ll wait for you on the main road just where it joins the village road. It will all look natural.”

“We can try it, anyway,” Sheila said. After all, perhaps Aunt Marta was ill. Perhaps she would be unable to walk very far. “I think that’s a brilliant idea.”

Her words pleased him. “Got to use your wits nowadays,” he said, with a knowing air.

“Do you do much of this kind of work?”

“Driving’s my job. Confidential kind of work. People like you, miss, on special missions. I never know what they are doing, but you can’t help wondering.”

“You must never let yourself wonder too much,” Sheila said coldly. She had begun to feel some brake must be put on this man’s quick wits.

“Oh, no, miss,” Treltsch said hastily. “I never say a thing. I’m the silent type.” He looked at her respectfully with a touch of uneasiness, and didn’t speak again. Thunder and damnation, he was thinking, who in God’s world would have thought she was one of those stuck-up martinets? He ought to have guessed, though, by the way she talked; all very exact and proper, as if she were reading a damned grammar-book. That was the way they talked in the big cities, in the best houses. Well, some day his children would be talking like that. And he’d have that piece of land he had already chosen in south-western Poland, with a view of a mountain, too. And he’d have his Polish workers. And he’d give his children the best education. They’d be talking like that. They’d be driving round the countryside in their own cars. He began to whistle again, softly. She didn’t seem to object to his whistling, anyway. She was looking as if she were worrying about getting these three Poles to Warsaw. Well, that was her picnic. That’s why they paid her and gave her such fine clothes. Old Papa Engelmann would look after her well. Funny that a young girl could go for an old man. Plenty of the younger officers would give her a better time. A nice little piece like that…

“What’s that?” Sheila asked. Unnecessarily. She had learned to know what that sound was. But the quietness of this empty stretch of road, the sleepy curve shielded by trees which they were now approaching, the low mass of grey clouds above their heads, had made the shots all the more unexpected.

“One of our patrols. I can hear a car,” Treltsch said evenly. He swung the wheel to guide the car carefully round the curve of dense pine-trees. They could see the short strip of road ahead of them now, before it twisted again to resume its usual straight line. They could see the German patrol. Six grey-coated men lying on the road, their arms outstretched, their legs twisted, their bodies sprawled as they had been thrown from their motor-cycles. The noise of the ‘car’ which Treltsch had heard was the running engines of two of these motor-cycles as they lay on their sides near the men, their wheels turning helplessly. The other four had travelled aimlessly into the muddy ditches and lay as grotesquely silent as their riders.

Men in ragged uniforms, in civilian jackets and cloth caps were kneeling beside the dead soldiers. They looked up as the grey car swept quietly round the corner. Treltsch’s careful driving and the noise of the motor-cycles had no doubt deadened the sound of the car’s approach. For the fraction of a second Sheila saw the white faces staring up at the car, saw the men kneeling as if they would never rise. Treltsch, his face grim and hard, pressed the accelerator so that the car seemed to leap at the men. The car jumped as it struck the German corpses in its path, but the Poles had scattered to the side of the road.

Sheila was knocked forward on her knees. She had thrown up her arm to protect her face as she fell. There was a sharp blow on her elbow, a wrench on the back of her neck as her forehead struck against her own arm and the arm struck the dash-board of the car.

Treltsch cursed and swung the car with one hand towards the last of the men as they reached the ditch. In the other hand, he held his revolver. Before he could aim it at the faces so near them, the wind-screen had a sudden sunburst of fine cracks, the car plunged crazily down into the broad ditch, and the brakes screamed frenziedly. The car rocked, remained upright. But the deep, soft mud held the churning wheels fast. Treltsch’s last curse was unfinished. He screamed as the brakes had screamed. He tried to rise, stiffly, his knuckles round the steering-wheel showed white as his weight was held by that arm for a moment. Then the arm bent slowly, and he fell forward.

Sheila stared sideways at the unmoving man beside her. She tried to raise her head away from her arm, tried to rise from her knees. She closed her eyes as she heard the Polish voice giving commands. “Hurry. Weapons, coats, papers off these sons of bitches. Silence the cycles and car, or we shan’t hear anything else coming. Hurry.”

Some one was standing beside the car on Sheila’s side. She could hear his heavy breathing, as if in that last desperate leap for the ditch the wind had been knocked out of the man.

“Two dead here, rotmistrz,” his voice said slowly. “Two dead here, captain.”

Sheila opened her eyes, saw the man’s mud-smeared face within a foot of hers.

She tried to smile. “Not dead,” she said. “I’m not dead.”

The man had whipped his revolver into sight as she spoke. And then, instead of shooting, he stared. He smiled, too, and the smile broadened into a laugh.

“What’s there to laugh at?” the captain’s voice asked savagely.

“She’s only saying her prayers. She’s not dead. She says she’s not dead. She says, cool as you like, ‘Im not dead.’”

“She soon will be,” a third voice said grimly. “We’ve finished over here, rotmistrz. We’re waiting.”

“Scatter. Get into cover. Don’t drop anything.”

“Yes, rotmistrz.”

The mud-stained man said, “What are we going to do with her? I shouldn’t have listened to her. ‘Not dead,’ she says, and spoils my aim.”

Sheila tried to rise to her feet. She looked up at the man who now stood beside the mud-stained man. A captain. A cavalry captain if he were called rotmistrz.

“Wisniewski,” she said desperately. “Adam Wisniewski.”

The captain’s hard blue eyes narrowed. He reached into the car and pulled her roughly to her feet.

“Korytów,” Sheila said, “Korytów is in danger.”

The captain’s hard look, compressed lips, lowered brows were unchanged, but he had opened the door of the car. He was still pulling her. The pain circled from the nape of her neck up round her head.

“I should have shot her when my blood was hot. But, God help me, I’ve never shot a woman,” the first man was protesting.

Sheila said, “Adam Wisniewski,” and stumbled forward. Her hat was somewhere in the car. And her gloves. And her fine new coat with Treltsch’s blood over it had caught in the doorway and had fallen off her shoulders as she had been dragged out. It trailed over the car-step, and a large mud-coloured footstep was blotted on its lapel. She still held her handbag. She would die, it seemed, still clutching it. But the mud-stained man had noticed it, too. He snatched it out of her hand and opened it.

He said in amazement, “No gun, rotmistrz! Only papers.”

“Don’t lose them,” Sheila said, “don’t lose them.” She looked anxiously at the man. She put her hands up to hold her head and closed her eyes.

“Keep a grip on her arm, Jan,” the captain was saying. “No time to lose now. Keep going.” He took the bag from Jan and stuffed it inside his jacket. “I’ll have a look at these later. Keep going, Jan.”

They hurried her between them to a place in the ditch where branches had been thrown over the deep mud. They crossed it at a run, dragging the girl. Jan stopped to pull the branches away and scatter them under the trees. Then they were hurrying and twisting through the pines. The captain held Sheila’s arm in a vice-like grip. Jan, when he caught up with them, followed with his revolver held pointed at the small of her back.

Sheila kept saying, “Korytów. Korytów. We are going away from Korytów.”

“Keep quiet!” The captain shook her impatiently. His grip twisted, and the pain in her arm silenced her. They entered the wood. On the road behind them was the heavy peace of autumn dusk.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”