The Unconquerable (20)

By:

November 13, 2014

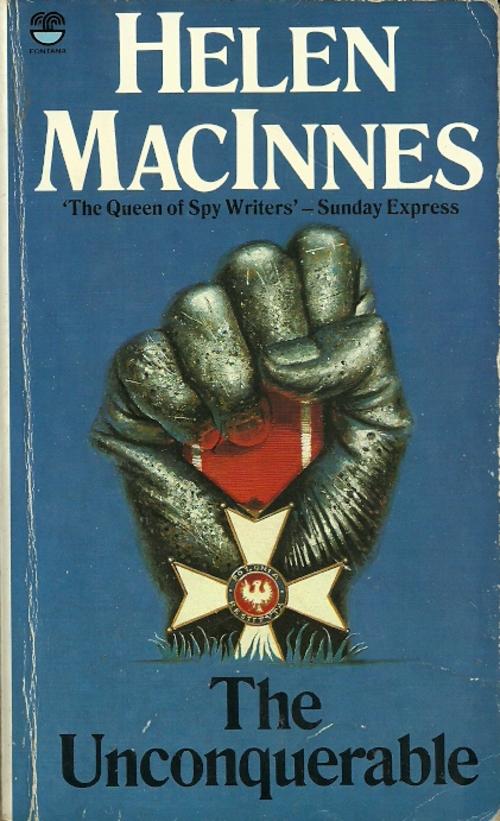

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Helen MacInnes’s 1944 novel The Unconquerable (later reissued as While We Still Live), an espionage adventure that pits an innocent English woman against both Nazis and resistance fighters in occupied Poland. MacInnes, it’s worth noting, was married to a British intelligence agent, which may explain what one hears is the amazing accuracy of her story’s details. Under the editorship of HILOBROW’s Joshua Glenn, the Save the Adventure book club will reissue The Unconquerable as an e-book for the first time ever. Enjoy!

The first Germans entered Warsaw. The graves along the streets and gardens welcomed them. Rough wooden crosses were the banners which the city raised. The withering flowers on the unknown graves were the petals strewn in the conqueror’s path.

The people, too busy with their search for food and water and jobs, for scattered families and rooms where they could live now that the Germans occupied so many houses, hardly seemed to notice the green-grey uniforms crowding their streets. Ignore them was the unconscious reaction. The Germans offered chocolate bars to children and took photographs. They offered bread and soup to the less proud and took more photographs. (Later the bill for soup and bread was charged to the city; no photographs were taken of that event!)

But the people seemed coldly oblivious. They were like men who have been sharply awakened from an evil dream who moved and talked with the dream still haunting them. If there was bitterness in their hearts for their failure, bitterness on their tongues for those they blamed, still more bitter were their eyes as they ignored the Germans doling out little benefits with so much fanfare. The Nazis gave so little compared to what they had destroyed. The chocolate offered to a starving Polish child, even without the news-reel cameras grinding in the background, was merely added insult to his mother’s sufferings. The smiling, confident Germans would have been amazed, even indignant, if that had been pointed out to them. Sometimes Sheila wished she could enjoy that luxury.

But it was luxury to be alive at all. Even after a week of silent guns she was still amazed that any people should still be left. She was still more amazed that she should be counted among them. As she walked along the partly cleared streets towards Central Station she could only think, “In spite of all this some of us still live. Some of us still have homes. And some,” as she noted a man and woman hawking a tray of stockings outside a boarded-up shop, “some are beginning to plan their lives again.” The extraordinary thing about human beings was their resilience.

She attempted a short cut to the station and entered a quiet thoroughfare to reach Marszalkowska Avenue. But its end which joined the larger street was still blocked by an immense barricade. Men were even working now to tear it down. They worked grimly. No doubt they were thinking of how they had planned to retreat and fight behind these barricades. They had built them strong. But the failing supply of ammunition, the lack of water, had beaten them. And now the order had been given that Polish hands must tear the barricades down, so that the Nazis could stroll through the street.

One of the men straightened his back, pulled on his well-cut jacket with grimy hands. Another man had stepped forward to take his place; each citizen gave so much of his time as he passed by the barricades which ringed the centre of the city; each stepped forward, worked for the same period of time, and then relinquished his place to another. The man in the well-cut suit was trying to wipe off the dust on his hands. He noticed Sheila’s hesitation as she calculated what would now be the quickest way of reaching Central Station. She must not be late — not for her very first meeting with Mr Hofmeyer.

“Trying to get to Marszalkowska?” he asked. “You’ll have to make a detour. I’m going there. I’ll show you the quickest way.”

“Thank you,” Sheila said in relief.

“Stranger?” the man said. He finished rubbing his hands. He wore the neat black jacket and striped trousers of a once prosperous business-man.

“Yes. British.”

“H’m.” The man looked sourly at her. After that he didn’t speak until they had reached Marszalkowska Avenue. “There you are,” he said abruptly.

“Thank you again.” Her smile hesitated; this man didn’t want any smiles from foreigners. But he had noticed the expression in her eyes and halted unexpectedly.

“What are you doing here?”

“I stayed. I thought I could help.”

“H’m. You’re one of the few foreigners who did, then.”

“I’m sorry,” Sheila said miserably.

The man stared at her. He noticed the bloodstains still smudging her coat, its singed cuff, the red skinless flesh on her left hand, her bare legs, her worn shoes.

“I’m sorry, too,” he said gruffly. “Good day.” But his voice had lost its hard edge, and the bitterness in his face eased for a moment. “Please forgive me,” he said wearily, and then he left her.

It was a subdued Sheila who crossed the street and reached Central Station. Its twisted, blackened ruins increased her depression.

Hofmeyer was already there. He was walking with his light step quickly towards her.

“Good day, Anna,” he said in German. “I was beginning to think that you didn’t get my message this morning.” He caught her arm to turn her round so that she faced the way she had come. “This way. I am taking you to my new office. I realized you might not be able to find it easily, but you would certainly know the way to the station at least. Besides I wanted to have a little talk.”

“I’m sorry I’m late. I took a short cut, which was like most short cuts.”

Hofmeyer’s grip tightened on her warningly. “Look happier,” he said in a low voice, his face still looking straight ahead of him. “Our friends are everywhere now.”

He spoke the truth. Apart from the uniforms, the Germans who had hidden themselves in Warsaw had come forth to enjoy their triumph. They were dressed like Poles. They were trying to look like Poles, for now their job would be to mix with Poles and spy on them. But to-day there was that certain exultation in their faces, which men find difficult to hide.

“They’ve won,” Hofmeyer said in that very low voice, his lips scarcely moving. “Take a good look, Anna. That’s how you feel when you win.”

“It must be a pleasant feeling,” Sheila said bitterly, speaking as secretly as her companion had done.

“And that’s why you must look happier. You’re one of them now.”

“You depress me still more.”

“Fortunately, this walk to my new office isn’t so very long. You can let your face relax there. Only you must guard your tongue once you are inside. Speak German at all times. If we have any private talking to do, then we shall take a little walk through the streets. And whenever we are taking such a walk, you are to talk about the weather as soon as you feel my hand knock against yours.”

Sheila looked surprised.

“Just as the walls have ears in a German office, so the streets have ears in a German-controlled town. Now is there anything to report before we reach the office?”

“The man Henryk has been to see me.”

“Henryk? You mean Heinrich Dittmar? The devil he did.” He was silent for some paces. “Well, I won’t deny that was a surprise. What did he want?”

“He called it a ‘social call.’ But I got the feeling that he disliked you, and — please don’t think I’m exaggerating — I thought he would like to do you some harm.”

Hofmeyer didn’t laugh. He nodded grimly and said, “You are not far wrong there. Any further — feelings?”

“He was more interested in me than was necessary. I’ve worried ever since. What could have given him a suspicion?”

“Not a suspicion. At least, we must hope not. Heinrich Dittmar is well known. If he must work with women he likes them young and pretty. Elzbieta was very pretty once, you know.”

“But I am under your orders.”

“What’s that to Dittmar? My dear Anna, if you could see the energy and tempers that are wasted on little jealousies in the Party you’d never criticize the democracies again. I have just been through a particularly tiresome session. About offices. Yes, you may laugh, but it’s true. We squabble over offices — which are the most comfortable and the most impressive. It is a point of honour with small minds to put such emphasis on material display of importance. We are now fighting over the housing of our staffs and even about the staffs themselves. We all want the best, to show how much authority we have. We are jockeying for our future positions and power.”

“It sounds fantastic. Then their supposedly united front is… ?”

“No. It’s united in the main things. They know that if they aren’t united, then the little butcher or grocer of a Saxon village would cease being the Gauleiter of hundreds of square miles. The debt-haunted Berlin clerk would stop travelling first-class, staying at the best hotels, wouldn’t have all the women and expensive dinners he likes to enjoy. The dull school-teacher from Bavaria would no longer be able to have a mansion and motor-car and servants. The ——” His hand brushed heavily against her arm.

Sheila hesitated, and then the words rushed out on top of each other. “It is getting so cold, and the rain is miserable now that it has come.”

“Good,” said Hofmeyer, after a pause and when the man who had walked so closely beside them had passed by. “But there’s no need for such zest. A bored remark will do.”

Sheila said nothing.

“Oh, it was quite good for a first try,” Hofmeyer added encouragingly. “Now, where were we? Ah, yes — the little jealousies behind the scenes. No, don’t hope that a miracle will come of them. Remember that this is the end of one campaign, and that many of them believe it is all they need to fight. Many think that England and France will ask for peace, and that they will then have plenty of time to plan for the next phase. They want to immobilize the biggest countries, make them disgusted with their leaders, play on their peoples’ natural tendencies to reproach and criticize each other. Then they’ll take over the small countries one by one, and the bigger countries will be in such a state of uncertainty that they will be unable to fight any war. So, thinking these things, the Nazis can relax and be their own nasty little selves. Before the campaign everything was forgotten except the need to win. Or else, as I said the butcher and grocer and clerk and school-teacher would all be back where they started.”

“But all Nazis can’t have power.”

“No. But they all think they share in the loot. They all see personal prosperity ahead of them at other nations’ expense. Meanwhile, during this lull in action, they are flown with insolence and wine. They are confident enough to indulge in petty quarrelling. Recently I’ve felt that I have missed my true vocation. I should have been a tight-rope walker.”

“Have you never felt like that before?”

“Not quite so constantly.” Hofmeyer smiled suddenly and said, “If this weather continues we must have glass in our windows.”

Sheila looked at the gaping holes round them and said, in what she hoped was a bored enough voice, “Yes, indeed.”

There was a pause for safety. And then Hofmeyer said half amusedly, “Dittmar’s interest in you is most annoying. It changes my plans for you entirely. I can’t ship you back to England now.”

“No. I suppose either I should have to go on pretending to be a German agent in London, or you would all be in danger here. I’m your discovery; if I behave suspiciously then you’ll be suspected too.”

“Don’t worry. Now that you’ve given us warning about Dittmar, Olszak and I can make our plans.” He looked at her and smiled. “You might have the makings of an agent after all. Perhaps Olszak was right about hereditary traits.”

Sheila smiled happily at the oblique mention of her father. Hofmeyer had paid her a high compliment.

“Of course, if you go back to England,” Hofmeyer went on, “you could always disappear as effectively as Margareta Koch. In your case it would mean complete change of identity for the duration of the war.”

“In her case it was… ?”

Herr Hofmeyer’s square white face looked blandly at a group of German soldiers. “Exactly,” he said. Then. “She found out too much about us. Dear me, what a lot of cameras the German Army has!”

They had now left Marszalkowska for a quieter side-street of balconies and three-storeyed houses. The architecture had been noble. No expense had been spared in workmanship. Hofmeyer halted before one of the large double doors.

“Nothing private to be discussed,” he said so quietly that Sheila wondered if she had heard all his words. She hadn’t expected the journey to end so quickly; she still had questions to ask.

“Madame Aleksander and Korytów?” she asked hurriedly.

“Yes. But don’t be too sympathetic.”

The hall was of marble, with a floor of great beauty. This house had suffered less than the others in the street, and that was why it had been chosen by the Germans. One of the reasons, at least. Another might be its wealth. The ground-floor rooms seemed empty except for workmen. On the broad curve of stairs she noted the elaborate pattern of marble underfoot, the pieces of sculpture still standing in the wall-niches. Even in spite of traces of dust and water the beauty of the house still existed.

“Who owned this house?” she asked as naturally as she could as they reached the thick carpets of the first floor. Hofmeyer must have thought her question harmless, for he smiled and nodded approvingly.

“A lawyer. He is an officer in the army, but if he comes back here to see his wife and daughter he will find that his property has been confiscated. He has been known to have expressed opinions against us in the past. The wife and daughter were told to leave two days ago. So the house is empty, except for some workmen doing repairs and some cleaners mopping up after them. In the next few weeks the other rooms will all be occupied as office suites. Surplus furniture is being removed to Germany along with some of these paintings. They are too valuable for a private house. They belong to our museums or public buildings.”

Sheila thought of the lawyer’s wife and daughter. Like the dispossessed in Western Poland, they had probably been allowed to take one small bag with them.

Hofmeyer understood her silence. Perhaps he himself had also thought of the wife and daughter. “Plenty of pretty dresses and hats and furs still in the wardrobes,” he said. His smile was bitter. “Do you need some clothes? They’ll be removed soon.” His smile deepened as he saw the look of disgust on her face. He opened the door of his suite of rooms.

They were in what must have been the library. Next to it was a large, extremely comfortable study, and the room beyond that was a bedroom. There was a feeling of great comfort and charm in the room’s arrangement. The lawyer had been proud of his home, and the happiness of the family still lingered inside the house.

“You see, I shall live here. It makes my business more efficient,” Hofmeyer said as they finished the tour of inspection and returned to the library. “Now sit down, Fräulein Braun. We can talk at last. This room will be the outside office. You will work here with two typists whom I am now choosing. Volksdeutsche, of course. But even so, they will be kept to deal with the problems of table delicacies only. My own office will be that study next door. Fortunately, I had copies of my files which were all destroyed by fire at the Old Square, so once they are installed here you can start work. These bookshelves will be cleared, of course, to make room for our records. The books will be shipped home with the contents of the Warsaw libraries and private collections. A defeated nation does not need valuable books.”

Home… Home, in this office, now meant Germany. But something in Hofmeyer’s direct stare at the wall of books in front of him interrupted Sheila’s thoughts. “The walls have ears,” he had warned in the street. She followed his stare. The walls have ears. And he had drawn her attention particularly to the books. Yes, a dictaphone might very well be hidden somewhere behind these books. She wondered what a dictaphone looked like. It was slightly comic to be dominated by a little mechanical device which you had never seen. Comic? On second thoughts the joke turned sour. It must be quite a strain to live with it constantly.

“Do you expect many Polish customers?” she asked. I hope to God none of them speak their minds in this room, she thought.

“Why not? The Poles have known this firm for many years, and if they can’t pay me in money then they can pay in jewellery or valuables. Besides, I have my clients in Sweden and Switzerland to consider. We need their foreign money. As for my political position, the Polish police hadn’t time to publicize their search for me. Colonel Bolt was killed in the siege. No more than six others at his headquarters knew about me. Five of these have already been arrested by us. Kordus alone is unaccounted for. It won’t be long before we have him too. So, to the Poles, I am still a friend.”

“I see.”

“Now, here are two telephone numbers. One is for the ’phone in this office: 4-3210. One for the private ’phone in my own room: 4-6636.”

As he repeated these numbers slowly he extracted a small piece of paper from an inside pocket and handed it over to her with a gesture of silence. On it was a third number: 6-2136. Underneath the numbers was written “Emergency only. Leave message if unable to reach me.” Sheila concentrated on the number. Hofmeyer must have another refuge. The two numbers for this address belonged to the same telephone district, that of 4. But the special number belonged to 6. She handed the sheet of paper back to him.

“Cigarette?” he asked, and opened his case. She took one, still memorizing the numbers, and watched him strike a match.

“What were the numbers?” he asked.

“Business number: 4-3210. Special number: 4-6636.” Very special number: 6-2136; 6-2136….

They both watched the piece of paper curl into a grey tissue, watched Hofmeyer’s pencil chop it up until all that remained in the ash-tray was a fine powder.

“Talking of the Poles,” Hofmeyer said suddenly, “how are your specially chosen friends?”

“I wanted to ask you about them. Frankly, I am worried. I understood that you wanted me to live with Madame Aleksander meanwhile?”

“That was the plan. Stay close beside her and meet her friends.”

“She is recovering from her illness. And she wants to leave Warsaw. She talks continually of going back to Korytów and looking for the children.”

“But she can’t, for then you will have no excuse for staying where you are. Your patient work all this summer will be quite undone. Are you convinced that you can’t persuade her to stay?”

“I have already tried. Tactfully. For invalids are always suspicious. They lie in bed and brood. If I persuade her too much she may even turn against me. If she insists on going to Korytów shall I accompany her?”

“Out of the question. Absolutely not.” Hofmeyer rose with one of his surprisingly quick movements and searched for an atlas among the reference books. He opened it at Central Poland. “Out of the question, Fräulein Braun. See here. Korytów is too insignificant to be marked on this map, but roughly that is its position. Here. South of Lowicz. Isn’t that so?”

“Yes.”

“The line between German Poland and Occupied Poland, or the Generalgouvernement, will run through that district. The proclamation of the partition of Poland will be published to-morrow. It will be put into effect by the twenty-eighth of October. If the Aleksander woman is allowed to return to Korytów she may be in the incorporated part of Poland. And that means that she would have no contact with her important friends left in Warsaw. She would be quite useless to you for our purposes. You see, the western part of Poland, from the Carpathians just west of Zakopane in the south to the East Prussian border in the north, will become part of Germany. All property is ours. The Poles will be killed or kept for serf labour. That part of the country will be made completely German this time. And there will be no communication allowed between German Poland and Occupied Poland. If Madame Aleksander were cut off from us here in War Saw by going to Korytów you would lose your one asset. She will be entirely eliminated if Korytów lies west of the boundary line between German Poland and Occupied Poland. Her lands will be needed for German settlers from the Baltic States. She may be executed for treason. She may be shipped in a cattle-truck to Germany, or to the northeastern plains of Poland where the weather will take care of those not strong enough to labour for us. So, until we know the definite boundary line of the partition of Poland, she must be kept in Warsaw. Do you understand?”

“Yes, Herr Hofmeyer.”

“Let me see the assets you have in Madame Aleksander,” Hofmeyer was saying as if he were counting the good points in a horse at a fair. “She has one son in diplomatic circles, another who had many friends in Government service, a brother who has the trust of the Warsaw University faculty, a cousin who is a general, another who is a bishop, another was a member of that band of parliamentary fools they called a sejm. Yes, it was a powerful family, and its name still carries respect among the Poles.”

Sheila stared, fascinated. She hadn’t known all that. “Her daughter-in-law comes of a powerful commercial clan, I believe,” she said, remembering the ill-fated Eugenia. “It owned many big businesses and shops throughout Poland.”

“Yes, a powerful family. That was why I wanted you to win their trust. For our office has two functions. One is to be in contact with people who might hear important news and unwittingly supply us with it. The other is to try to persuade some Poles to work with our Generalgouvernement. That would always help us initially. Later, when their usefulness to us was over, they could be disposed of like the other Poles.”

Hofmeyer was pacing the room now. His whole performance was convincing. It was cold, callous, and calculating. Whoever was interested in the concealed dictaphone would only find two worried Germans shaping their plans to bring honour to themselves and power to their Reich.

Hofmeyer stopped his pacing abruptly. “I have an idea, but I must discuss it with another department first. If they approve it then you will make a quick journey to Korytów and bring back the children to Madame Aleksander and Warsaw. That will make you a heroine in Polish eyes, and your position will be assured. You can invent the difficulties you had to face. Actually, from this other department I hope to get facilities to make your journey there very simple. I shall ’phone you to-morrow and give you instructions.”

“The ’phone wasn’t working this morning. I think it’s probably going to be out of order for some days.”

“Nonsense, Fräulein Braun. Do you think that we shall leave that excellent district, which has been less destroyed than any other, unrequisitioned? And naturally, if our officers and officials are going to take over those apartments we shall certainly see all repairs are done there before other districts. You are now living under your country’s rule, Fräulein Braun, and not under slipshod English methods. I shouldn’t be surprised to hear that our workmen have already started on their job in that quarter while you were absent.”

Sheila said meekly, “Yes, Herr Hofmeyer,” and watched Hofmeyer’s grave wink. That last sentence had seemed peculiar in many ways. Why had he chosen to add the unnecessary “while you were absent” phrase? And why nod as emphasis to the “you”? He was staring so fixedly now at the bookcases that she realized he was trying to warn her of something by the association of ideas. She looked at the bookshelves, too, and she thought of a dictaphone. That was it: the workmen might install a dictaphone. The walls had ears. In her simple-minded way she had thought that only meant the walls here. Now Hofmeyer, who had sensed her mistake, was trying to warn her. He was watching her face, and he now showed the relief of a man who had remembered in time to give an added caution, and who saw that it had been accepted.

“You had better return to the Aleksander woman now and stay with her until you hear from me. Tell her about your new position here; say that I am a friend of the Poles. Arouse no suspicion. Find out, meanwhile, what you can about the members of her family.”

Sheila rose. Hofmeyer was already on his way to the study to answer an insistent telephone bell. “Heilitler!” he snapped, his hands deep in his pockets.

“’tler,” echoed Sheila obediently, and closed the library door.

She clutched her handbag firmly as she walked down Marszalkowska, turned left along Jerozolimskie Street. For inside the bag was her only security now: her identification and membership card for the Auslands-Organisation with the faint stamp across its surface reading SPECIAL SERVICE. After that conversation for the benefit of a dictaphone Anna Braun was no longer a mere name on a piece of paper.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”