The Unconquerable (12)

By:

September 18, 2014

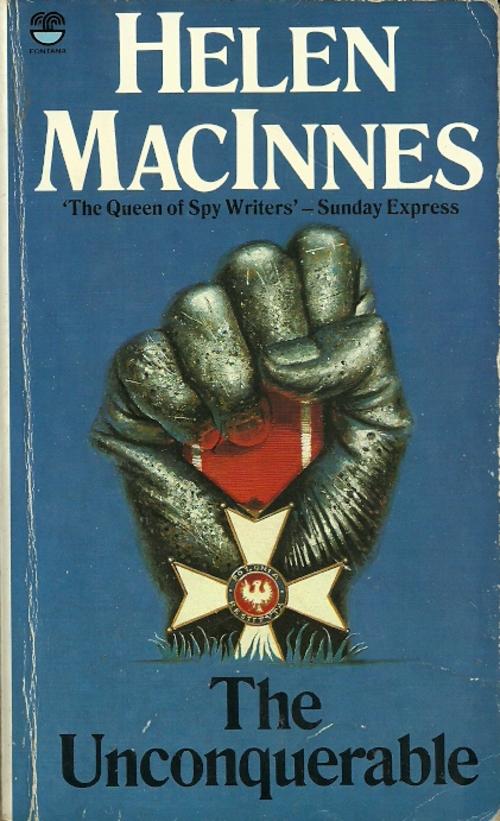

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Helen MacInnes’s 1944 novel The Unconquerable (later reissued as While We Still Live), an espionage adventure that pits an innocent English woman against both Nazis and resistance fighters in occupied Poland. MacInnes, it’s worth noting, was married to a British intelligence agent, which may explain what one hears is the amazing accuracy of her story’s details. Under the editorship of HILOBROW’s Joshua Glenn, the Save the Adventure book club will reissue The Unconquerable as an e-book for the first time ever. Enjoy!

Sometimes Sheila, when she had an interval free for thinking, would imagine that the last days of Warsaw were the very essence of Greek tragedy. You knew there could be no hope, no happy ending. Yet this knowledge did not end the suspense. The drama mounted steadily, intensely, until the last scene reached the final anguish. For the very character of these people of Warsaw would not let them end their miseries. If they had been made of more selfish, worldly stuff, then they would have found an excuse long before the end to save themselves from the full course of the tragedy. Their pride, their nationalism, their courage, their fatalism made their actions inevitable. Even their individualism, which had served them so ill in the past, now strengthened their resistance. Their strong historical ties bound them to their decision. Above all, the vision of another captivity made life seem something not to be hoarded.

The American, grey-faced and taciturn, had looked at her curiously for a moment when under the influence of a plate of hot food, she had told him these thoughts. They had met for that promised dinner in the restaurant of the Hotel Europejski. Barbara, at the last moment, had been unable to come. One of the other nurses had sprained an ankle, and Barbara insisted on doing extra night duty with her children. She had also insisted that Sheila should go to the restaurant. Sheila, she had said with much truth, was still not completely well, was working too hard, was in need of a warm meal and a two-hour rest; and Russell Stevens would be just the right person to cheer her up. So Barbara had insisted. So had Stevens. And here Sheila was, trying to concentrate on a kind of soup made with boiled meat and rice which was the regulated and only choice in all the restaurants, trying to think of something to say which wouldn’t deal with the war. It was difficult.

Stevens must have felt that too. He looked at his plate speculatively. “Ever eaten here before?”

“No. In June Barbara and I ate at the smaller places.” She smiled. “We didn’t have any expense accounts, you know.”

He laughed in spite of himself. “It’s a pity you didn’t see some of their chief places. Good food and wine. Boy, I lie awake and dream of them now.”

‘This food is better than I’ve, tasted for a long time.”

“Which proves one of my theories. Good cooking is only the daughter of invention. The more disguises you have for

food, the bigger chef you are. Now this stuff ——” He jabbed

at his plate with his fork. “Well, we all know just what kind of meat is left in Warsaw. I believe even cardboard would taste good if it had the proper seasoning and sauces.”

“I’m too hungry to be disillusioned.” Sheila said. She tried not to think of the horse which had been machine-gunned to-day in the street near the children’s hostel. Nor to think of its skeleton, stripped bare only an hour later.

She tried very hard to look round the large room nonchalantly. “Not so many people here to-night,” she began, but the American’s amused smile stopped her.

“I guess that was what you might call a light conversational gambit.”

“There’s enough heavy conversation from those guns.” Sheila now gave up all pretence of not appearing to listen to the constant, methodically timed shells. “Twenty hours now,” she said. “Twenty hours without pausing for five minutes.”

“Don’t tell me you’re still counting them?”

“Why do I amuse you so much?” she demanded frankly and suddenly.

He looked as guilty as a small boy caught inside a jam cupboard. “Not amuse,” he said, “There’s the wrong sound to that word.”

“But you laugh at me. Half the time you are laughing inside yourself. What’s so funny about me?”

Stevens was taken aback. “You’ve got me all wrong,” he protested too vehemently. Amused? He wondered. Surprised would be nearer it. She surprised him into smiling. He was feeling cheerier than he had felt for almost a week now.

“What have you been doing since you left the apartment?” he asked.

“Reading simple Polish stories to the younger children. Drawing funny pictures. Making rabbits out of handkerchiefs. Barbara won’t let me do much of the heavier work yet. Rather funny, isn’t it, to spend the last six days since I’ve seen you doing nothing but thinking up things so that the children won’t think of other things? And what have you been doing?”

“The usual.”

“The last of the diplomats and the journalists left four days ago.”

“Meaning, what am I still doing here? Much the same as you are. Probably less.” He smiled and added, “How’s friend Olszak?”

Sheila was smiling too, but her eyes were watchful. “Tell me, Russell, did you ask me to dinner to-night because you were being polite, or because you wanted to keep track of Sheila Matthews?”

He wasn’t smiling now, although this was the biggest surprise she had yet given him. “I had a much more natural reason than either of those,” he answered, and saw he had routed her. She was still watching him, but this time she wasn’t quite sure whether to be pleased at the implied compliment or to be afraid that she had seen a compliment where none was intended. She shifted her ground and got back to a safer level of conversation.

“What about your job?”

“That’s over, meanwhile. I think that I’ll get it back once I do get out of Poland. The New York office will come round to seeing it my way. If ever they wanted a big story, then this is the place to get it and not on the road to Rumania.” He was being casual about it, but Sheila guessed he was more worried than he sounded. He had been enthusiastic about his job; now, perhaps, he had ended the career he had chosen by his decision to stay here. He went on talking as if to persuade himself that all was well. “There’s one other American reporter left. He has the same ideas as I have. And my Swedish friend and several others on the staff of the American Bank are still here. The bank is going to keep open even if the Germans do take over. Then there are skeleton staffs at all the neutral embassies. So we aren’t the only foreigners left in Warsaw.”

“But why doesn’t your head office see it your way now? Why did you have to lose your job?”

“I’ll get it back again, perhaps. That’s more than you can say for the guys in this country. And, anyway, the New York office was probably right. It’s quite a chance that my big story will be cold news by the time I leave here.”

Sheila’s face was such a study in horror that a smile was forced out of him.

“But people have got to listen,” she said. “If they don’t then all this sacrifice is useless.”

“People react in ways you don’t expect. Some will see the writing on the wall and start taking action. Some will say it’s propaganda and war-mongering. And some will say that it’s all too tragic — give us something with a tune in it. Why should they listen, anyway? I agree with you, personally. But why should they? Why shouldn’t they just go on concentrating on pleasanter subjects?”

“Because it weakens them, because they are making them

selves incomplete, because ——” She floundered in her attempt

to express what she felt; her emotions were racing far ahead of the words on her tongue. She took a deep breath. “Look. This evening I arrived here babbling about Greek tragedy. Now I know I really meant it. For why did the Greeks believe so much in tragedy? They must have, or they couldn’t have written such good ones. Didn’t they believe that men must have a periodical house-cleaning in their minds and emotions? Wasn’t that why they gave men drama which roused their pity and fear? Pity was for the characters in the tragedy; fear was for the audience’s own chance of having the same kind of experience. Pity and fear together make a powerful purge for any mind. A public which won’t look at or listen to tragedy develops a sluggish mind. That’s what the ancient Greeks knew. And the richness of their minds has never been equalled.”

“Didn’t I hear some place that Athens once fell? And for good?”

“Yes, it fell when its people didn’t want to hear or believe unpleasant things.” Sheila relaxed again. “You see,” she said more quietly, “I really feel this. I really believe it. I am worried for those people outside: not the people here — I pity and I admire them. And I feel so angry when I see what is happening to them that I could go out and kill fifty Germans with my own bare hands. I could…. If I couldn’t I should be a callous wretch. But I worry…. Poland is nailed to the cross. And the rest of humanity will not be warned in time. If what you say is true, that your news of this siege will be cold news in a month or two, then this whole sacrifice is in vain.”

“You speak like a Pole.”

“No,” Sheila said slowly, “like a Scot. If I were a Pole then sacrifice in itself would be so noble that I shouldn’t worry about what it pays for. I can’t bear to see sacrifice wasted.”

The old waiter stood beside them. “Another alert has been sounded. The management offers the wine-cellars as suitable shelter.” He had said it so often in the last three weeks that he might have been announcing that veal was off the menu to-day. “This way,” he added, and waited for them to rise.

Stevens looked at Sheila with an eyebrow raised.

“No one bothers now,” she said, and Stevens shook his head at the waiter. The old man nodded and went slowly away as if he had expected that. His shoulders were bent, his feet hardly lifted off the ground. He was very old. He went to the other tables. Only three people rose, and these hurried out of doors with the business-like look of some duty to be done. Air-raid wardens, Sheila thought. They had probably come here to relax in an off-duty interval. But they had known there was no off-duty time for anyone when a big raid was announced.

“It must be a very big one,” Sheila said. “They don’t bother to let us know about the average ones now.”

The American nodded, lit another cigarette, and kept looking at her.

“The Greeks…” he said. “I believe we were talking about the Greeks. So you don’t believe in modern progress?”

“Bigger and better battles?” She flinched suddenly and caught the edge of the table. “Wish I didn’t do that,” she said shamefaced, after the explosion had died away.

“I was almost under the table myself at that moment.” They both laughed at that, rather too loudly, rather too vehemently.

“Let’s keep talking,” the American urged. I didn’t bring her here to have her talk, he thought, and laughed again, this time at himself.

“I’m talking too much,” Sheila said. “I don’t know why…. I don’t usually do this.”

“It’s a reaction to the bombs,” Stevens said gently. “Some people think of food all the time. Others want to sleep. Others want to make love. Others talk their heads off.”

Sheila smiled. “Unfortunate for you that I am the kind that…” She paused, as if she had said more than she should have.

“Talks,” the American concluded. He was laughing again. This is mad, he thought. The bombs are falling, and I’m laughing, and I haven’t much to laugh about; this evening isn’t going to end as I had planned at all. And I’m laughing. “You loved Andrew Aleksander like a brother, and you love me like a father confessor. What’s wrong with you, anyway? Or should I ask what’s wrong with Andrew or with me? Sorry; I see I’m embarrassing you. But some day I’d like to know.”

Sheila searched for one glove which was, as usual, under the table.

“I’d like to know too,” she said in a low voice, and accepted the glove from Stevens. There was a loose thread in its thumb. If she pulled it there would be a hole. It would be nice to outwit that rule, she thought. She pulled the thread. “Perhaps,” she said, “I want to be quite sure. As Barbara and Jan Reska were quite sure. I’d rather be alone all my life than not sure.” Her thumb came through the opened seam. “Stop doing that!” Stevens said. “You’re ruining it.”

She obeyed, much to her own surprise. And she suddenly knew what she had missed in Andrew: she wanted some one who could say “Stop doing that” now and again. She stared at Russell Stevens and thought, If I could mix you and Andrew together I’d be sure for the rest of my life.

“That was a big one,” Stevens said, listening. “Not far from here either.”

Sheila listened too. The long, dull roar from the east gathered intensity. She was suddenly afraid. Not for herself, not for the people round her. She rose, clutching her opened powder-box and lipstick. She jammed them into her bag as they were. “I must go,” she said.

“Hey, wait. The check,” Stevens called to her, and then as he saw her reaching the door he threw down some notes and coins on the table and started after her. He caught her arm as she stood hesitating in the doorway. Together they looked out into the street, dark under its black ceiling of smoke, as if they were reconnoitering. It didn’t take you long to develop little habits for self-preservation when you lived in a beleaguered city.

“Must we?” Stevens shouted.

Sheila nodded. We must, she told herself as she shrank from the noise and desolation of the street. She tried to shake herself free from the terror she had suddenly felt inside the restaurant. Some one called my name, some one called me, she was thinking. She tried to tell that to the serious face beside her, but she couldn’t. Stevens thought she was mad enough already. Perhaps she was. Sheila, Sheila! … How could she have heard that, inside the restaurant? How could anyone hear anything in this noise? The attack was more to the east of the city, towards the banks of the Vistula. The black smoke above the buildings became lined with orange. Somewhere there was fire. The American was looking down at her face. His grip tightened on her hand.

“Keep to the doorways. One at a time. When I say dodge, dodge,” he shouted, his mouth close to her ear. And then they were out into the street, into Marszalkowska Avenue, which had once been Warsaw’s gayest. The smart clothes, and the laughing voices, and the music and flowered window-boxes were gone. Only the trees still stood untouched in their neatly spaced circles of earth. A gaily striped awning flapped pathetically over a boarded window. The names over the shops and night-clubs and cafes were meaningless. In the roadway were fragments of bodies instead of taxicabs and red tram-cars. On the pavements were broken slabs of concrete, like the crushed remains of a huge ice floe ruptured by its own force. The people who walked there now were people with urgent, heart-twisting business. They walked quickly, dark figures moving through a nightmare of sound. There was the constant thunder of the encircling guns, the scream of plunging shells, the angry bark of planes, the whistle of dropping bombs, the roar of explosions, the staccato crescendo of machine-gun fire as a plane swept contemptuously low. Then suddenly there would be a terrifying blank of silence: a short lull to be counted only in moments, before the dentist’s drill plunged once again into the naked gum.

“Where?” Stevens asked in one of these moments.

“The children’s hostel,” Sheila had time to answer — and only time. For Stevens pushed her violently into the slight alcove of a boarded doorway and stood behind her, pinning her flat against, almost into, the wall. Then she heard the planes’ sudden roar as they swooped low, heard the sound of heavy hail on the pavement behind her. It was over before she had even grasped the coming of danger. In the street others were now stepping away from the wails or were rising from the ground where they had flung themselves. Two women remained on their knees to finish decently the prayer they had begun. Some bodies didn’t rise.

Stevens was staring at the sky beyond the University buildings which they were now approaching. The children’s hostel, Sheila had said. And the children’s hostel lay over there. Sheila was staring too. The low-hanging smoke clouds and the coming of night made it difficult to see clearly. And then the flames broke loose, leaping higher than the black clouds. Stevens pointed suddenly to the north and centre of the city. Flames all round were growing. The fires had begun. The clouds became scarlet. Sheila, remembering how Warsaw had been set on fire with incendiaries three nights ago after the water supply had been blasted into uselessness, gripped Stevens’ arm in desperation. Five hundred fires three nights ago. To-night, how many? They cast all caution aside and broke into a run towards the once pleasant garden and the once quiet square of houses.

“It’s the hostel,” Sheila kept saying. Stevens couldn’t hear her, but he knew, too. They were near enough to realize now that it could only be the hostel or one of the buildings beside it.

They reached the open square flanked by well-spaced, modern houses. One of the buildings was already being devoured by flames.

“It’s the hostel,” Sheila said again.

A warden shouted “No nearer: the walls are dangerous.” He pulled them roughly to a halt. “Help with the sandbags,” he yelled over his shoulder as he rushed towards a group of firemen, who were entering the other buildings. The incendiaries were just beginning their work on these houses. Fire-fighters, already on the roof-tops, were silhouetted against the knee-high fence of dancing flames. They were emptying the sandbags, which had once protected the buildings’ foundations from blast, over the greedy tongues. No water, Sheila remembered — no water. Stevens was already lifting a bag of sand on to his shoulders.

“Stay back,” he shouted to her. “You’ve been ill. You can’t manage this.” He pushed her towards a woman who had paused to wipe the streams of soot-stained perspiration out of her eyes. “She’s been ill,” he yelled in Polish, and plunged into the stream of people carrying the sandbags towards the doorways of the buildings. At the doorways they were met by others who came down the stairs to seize the bags and carry them up to the roof. The procession of old men, women, and boys never halted. Some of the younger men had found ladders and climbed, with their load of sand, like flies against the face of the buildings.

The woman pulled Sheila back roughly as she tried to lift a load of sand.

“It takes strength,” she said not unkindly, and pointed towards the centre of the square, towards the huddle of figures on the grass and flower-beds. “Help there!” She herself lifted a bag of sand and joined the moving stream as Stevens had done. Sheila looked towards the women lying on mattresses and blankets in the middle of the broad gardens. They must have been evacuated from the maternity hospital across the square. Nurses were with the women; ambulances were already arriving to take them to new quarters. A young girl, too young to be able to lift a sandbag, was dragging it slowly over the grass. The desperation on her face decided Sheila. She caught the other end of the bag. Singly you and I aren’t much good, she thought, but together we can help. And to help with the fire-fighting, now that the people inside the buildings had been evacuated, seemed the most important thing to her. Stevens passed them as he returned for another load. He saw Sheila and the girl. He shook his head, but his face relaxed for a moment.

On one of the roofs the fires had been extinguished. There was a sigh of relief from the crowd, almost swelling to a shout of triumph. But the neighbouring house had suddenly five little crowns of fire, and the people’s work was to begin all over again. Other houses were less lucky, there the flames were higher, but they were still fought. It was then that Sheila heard the increased drone of planes, like a mosquito’s hum mounting at her ear. The planes were so low that the flames, leaping above the pall of smoke, lighted their shark-like bellies. Some swooped even down between the flames. Machine-guns added their noise to the crackle and roar of fire. And the firemen, fighting their desperate battle on the roof-tops, suddenly ceased to be black silhouettes; there was nothing left but the orange flames. A woman cried out in helpless anger. Looking at the tense faces, blackened with smoke, wet with sweat, Sheila saw the woman’s impotent hate repeated in the bloodshot eyes as they stared at the sky.

Other fire-fighters had climbed to the roofs to replace those who had been murdered. And again, just as they seemed on the point of controlling the flames, the planes roared down. Again the machine-guns levelled them with the precision of scythe-strokes in a cornfield. Only two of them were left standing. The flames roared higher in triumph. Sand was useless now.

Stevens came to Sheila, pulled her hands from her eyes, and led her away from the building across the grass. “It’s no good,” he kept repeating, “it’s no good. Damn and blast them all to hell.” They sat down on an upturned barrow which one woman had trundled until the flames had shown them all that it was useless. He kept his face turned away from Sheila, and Sheila, weeping openly, looked towards the big building which had been the first to flare up. The red walls were now crumbling, falling like a row of children’s red and yellow blocks.

“That was where we were,” she said at last. “I wonder where Barbara took the children? Perhaps to the shelter?” She looked at the dark hump in the middle of the grassy square. She rose unsteadily. Her back felt as if it would never straighten, her feet were heavy, her hand throbbed. She looked at it curiously. It had a raw, shiny look. It began to throb and burn.

Stevens rose too, and then he looked at her and said, “What’s wrong?”

“I seem to have got my hand blistered. I can’t think when…. We’d better find Barbara. She will be with the children.”

He took her arm, and they walked towards the dark mound of earth. There was no one sheltering there. There were only two nurses who had come with some first-aid equipment. A line of injured women and men began to form. But the stock of medical supplies was low, and only the worst cases were being treated. The most desperate of these (“I told them the building was going to fall,” an exhausted warden was repeating to every one who would listen) were being taken to the emergency hospital cars which were now arriving.

“I’ll take you to the apartment. I’ve got some Vaseline there which will cover your hand. Hold it up. Don’t let the blood run down into it.” He turned away from the crowd of exhausted, worried, suffering people and led her away from the shelter.

“Barbara,” Sheila kept repeating. “We must find Barbara.” Every one kept repeating his words, as if by saying them over and over again other people might understand, as if he hadn’t heard himself speak and thought other people hadn’t heard him speak, as if… Sheila stopped thinking, for even her thoughts were repeating their words.

Stevens took her back across the plots of earth and grass towards the few people now left on the scene. There was no Barbara among them.

“She will have taken the children to some safe house,” he said. “They will be far from here by this time.” But his eyes still searched among the small groups of people. He felt Sheila tug his arm suddenly, and she was looking at a slender fair-haired girl standing silently beside an air-raid warden. Sheila’s heart leaped with relief. Stevens was smiling too. They hurried over. Just as they reached the fair-haired girl she turned round to face them. It wasn’t Barbara. Sheila’s relief turned to fear.

Stevens was saying to the silent man, “We are looking for a girl, blonde like this young lady with you here. She was one of the volunteer nurses with the refugee children. This evening there were three nurses and the children in that building which is almost burned out now. Where did they go? Do you know? Or where could we find out?”

The warden didn’t answer. His exhausted eyes were fixed on the American’s. He seemed to be trying to speak his sympathy, but no words came.

“They… ?” began Stevens, and stopped. Sheila was a statue beside him.

The man shook his head slowly, sadly. The girl beside him suddenly said in a frightening voice, “My sister was a nurse there. She was there.” The hopelessness and anguish in her face were answer enough.

Sheila turned away and began walking blindly towards the street.

“I’ll see you home,” Stevens said as he followed her, “and then I’ll come back and look. I’ll look until I find her. They don’t know what they are talking about. I’ll find her.”

They walked towards the centre of the town in silence. Stevens had slipped his arm round Sheila’s waist, and that helped to steady her. A first-aid car halted beside them in a ragged street.

“Any help needed?” the driver was saying. “I’ve room for one more.”

“Going south? Anywhere near Frascati Gardens?”

“As far as the Bracka Emergency Hospital.”

“That’s fine. Thanks.” Stevens jammed Sheila into the car on the front seat beside a sleeping man. “Stay at my apartment. I’ll be back as soon as possible. Medicine cabinet is next to the radio shelf.” He didn’t wait for them to drive off. He was already running back to the ruins of the children’s hostel.

The car plunged on, avoiding the holes in the road as if by a miracle. Sheila didn’t look at the people crowded into the fear seats of the car; she could hear them. She rested her throbbing left hand up against her shoulder and tried to avoid lurching into the sleeping man. Once the car twisted suddenly round the edge of an unexpected crater, and the man’s head fell sideways against her. She knew then that he wasn’t sleeping. She stared into the orange-streaked darkness and listened to the middle-aged driver, his good-humoured face puckered into fury, giving vent to his overcharged emotions with a constant stream of descriptive adjectives to fit the Germans.

At the hospital in Bracka Street — once a recreation hall — the car was emptied.

“I must return. I cannot take you farther. I am sorry.” The man’s gentle voice was in quiet contrast to his recent rage. He was leaning heavily over the wheel.

Sheila nodded to let him see she understood. She gave him her good hand. He held it and patted it gently.

“Go down that way,” he said, and pointed. “You will pass a large bank at the corner where Bracka meets Main Street. Keep on south, through the square, into Wieskska Street. Then you’ll be home. It’s quiet down there to-night.”

Sheila nodded again. She couldn’t even say thank you. She just stood there, looking at him, and nodding, and looking at him. The car started northward into the centre of the burning city.

Sheila’s body had become a machine. It was like a child’s toy which is wound up and runs on, unable to stop its rhythm long after it has struck a wall and lies sideways on the floor. Without thinking or seeing or feeling, she walked the distance to Stevens’ flat. At the same even, unfaltering pace she crossed torn streets, skirted shell-holes, stepped over debris; at the same even, unfaltering pace she climbed the stairs to Stevens’ rooms, and passed through the half-open doorway into the hall. Later, when she tried to recall that journey, all she could remember was that she saw the stranger drive away, and then she was standing in Madame Knast’s entrance-hall, listening to the voices which came from Stevens’ living-room, staring into the desolate kitchen.

Stevens’ two rooms were at the front of the building; the kitchen, across the hall opposite them, faced an enclosed garden. Once it had been as cheerful and gay as the trees and flowers it overlooked. Now, lit theatrically through its empty window by the reflected glow from the sky, it was desolate. The table was cluttered; dishes had fallen off the shelves and had smashed on the floor beneath. The curtains, without any glass to restrain them, were waving dolefully out into the garden. No one had lived in this kitchen for many days. Madame Knast’s rooms, farther along the hall, were silent too. Only from Stevens’ room came voices. Voices talking in English.

Sheila stood in the hall. The forsaken kitchen had sapped her will-power. The machine had run down: her legs wouldn’t move any more. She stood and looked at the kitchen. Once, she thought, this was the life of the house. Then the son had been lost. Madame Knast must be lost too. Lost, searching for her son. The curtains flapped back against the windowsill, then blew out into the night again. Madame Knast was lost. And Barbara was lost. Lost, lost, lost, the curtains echoed gently.

Stevens’ door creaked behind her. A man’s voice said in English, “Hello, I thought I heard some one. Come on in, whoever you are.” He was an American. When she didn’t move he repeated the invitation in Polish. Over his shoulder he called back in English into the room, “Tuck in your shirt, Jim. It’s a woman.”

The man came towards her curiously. “Come in,” he said for the third time, and touched her gently on the shoulder.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”