Fourth World (3)

By:

July 23, 2014

Third post in a series of five, by Adam McGovern, revisiting four decades of Jack Kirby’s “Fourth World” comic-book mythos.

Fourth World, Part 3

In Part 2, we made love, not intergalactic war — in Part 3 Kirby comes home again…

In the following years the Fourth World’s fanbase would expand, though the fans themselves would stay incurably disappointed — not only after other creative teams’ attempts at handling the characters, but even after Kirby was invited back by a wiser DC leadership to “conclude” the storyline in the oddly-titled 1985 graphic novel The Hunger Dogs. Some of Kirby’s biggest supporters feel that he had lost the thread by then, and that the epic he had been building a decade earlier could only be ill-served by skipping to a single final chapter. But, while it’s true that the project was marred by visual production errors and sometimes-choppy narrative meddling by DC, it was a satisfying coda by most measures. The unsatisfied fans tend to forget that Kirby’s archetypal tale was not truly timeless, but topical.

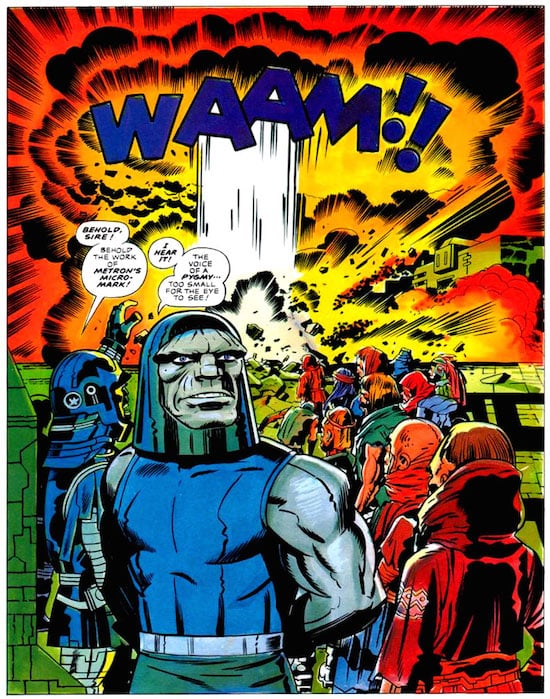

While Nietzsche reasoned that gods die when they cease to be believed in, Kirby realized that gods remain relevant for as long as they embody contemporary aspirations and anxieties. He thus embraced the 12-year gap by rethinking his story rather than trying to reconstruct his old intentions. The jump-cut was played for maximum surprise, and reflected the tone of new times. In a shift from the heated ideological contest of the early ’70s to the chilly nuclear deathwatch of the mid-’80s, the once-omnipotent Darkseid is now subordinate to his own system of automated mass destruction, and, among several of the old series’ cameo characters who are major players in this sequel, the optimistic, inquisitive New Genesis child Esak has become a cynical arms technician for Apokolips, after disillusionment at the disappearance of his mentor, Metron — a clear and melancholy metaphor for the abandoned idealism of the ’60s generation. (Esak, it is established, lost his Adonis good looks in an awful lab accident — perhaps around the time Jerry Rubin bought his first business suit.) The hiatus actually seems to have served Kirby well; the volatile Nixon years and the tense Reagan era were fertile ground for allegory, but it’s daunting to think of what Kirby’s fractious paragons would have had to do during the soporific Ford and Carter Administrations.

In any case, it isn’t the change of tone that sinks Hunger Dogs as a definitive denouement for many; it’s the confounding of prediction and consequent violation of action-adventure aesthetics. Rather than slaughter Darkseid as was believed to be his destiny, Orion has drifted toward pacifism, having fallen in a love that has softened his warrior’s heart and lessened his appetite for self-destruction. (This is Bekka, a goddess of New Genesis raised by her subversive father on Apokolips, but unlike Orion or Scott, aware of and reconciled to her dual heritage from the start, perhaps the clearest of several allegories Kirby made throughout his career to his indomitable wife Roz.) Orion returns to Apokolips not to confront his father but to rescue his mother, who’s been under an Eleanor of Aquitaine-like house arrest since his own birth and exile. As Darkseid futilely tries to slay him, Orion escapes with the two women in his life, and Apokolips is left to decline in its dead-end daydreams of conquest (a rot from the inside which Orion has been hastening by fomenting popular rebellion before he departs). Nothing could serve Kirby’s cause of free will better than denying prophecy and defying expectation, and he certainly accomplishes both here — though, for his last trick, he accurately prophesies the collapse of the Soviet bloc and the U.S.’s relative retreat from the nuclear brink. Thus Kirby reached a most fitting artistic closure, even if many who follow his work will never stop spoiling for the kind of fight that he himself had had his fill of in real life 40 years before.

Which is not to say that Hunger Dogs was anywhere near the end for Kirby’s characters, or even for Kirby’s involvement with them. It is rumored that Kirby’s plan for what became Hunger Dogs included the death of Orion and a number of other major characters in a crescendo closer to the one foretold in the original series. DC stepped in, fearful for the marketing potential of planned product tie-ins, and Kirby revised, in a strange case of economic censorship pushing an artist to greater creative resourcefulness. The first tie-ins were for Super Powers, a toy line and TV cartoon series featuring a few New Gods and many other DC stars, for which Kirby did some design and worked on the associated comic books. This project began an indefinite dispersal of the Fourth World characters throughout DC’s books, and somewhat diminished them in the process. Still, shortly thereafter, Kirby was able to retire largely on the royalties, an admirable move on DC’s part after his lifetime of groundbreaking achievement but little credit and no percentages.

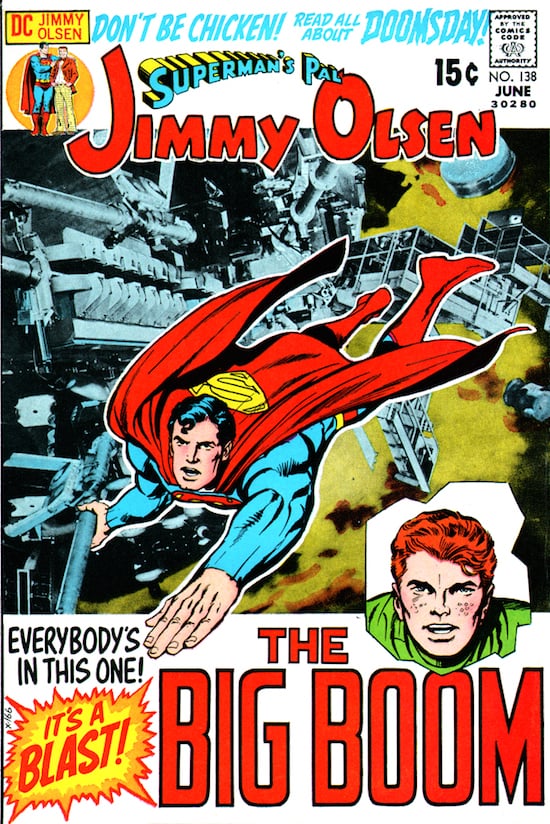

(At this late point it is pertinent to bring up a Kirby comic from long before, Jimmy Olsen. Produced concurrently with most of the Fourth World’s original lifespan, this improbable crack at the Superman second-stringer was an imaginative thrill-ride which showed Kirby at the height of his yarn-spinning powers, riffing on genetic engineering, nanotechnology, green-revolution forest-colonizers, and bohemian science geniuses decades before the era of Dolly the Sheep, blood-cell-size diagnostic cameras, Julia Butterfly Hill and Jaron Lanier was upon us. It also used the Fourth World as a nominal backdrop and a source of minor villains, in a token connection to the books that Kirby preferred to concentrate on — though in this, it ended up being the most accurate barometer of the pervasive yet perfunctory way in which the Fourth World would run through the DC line of later years.)

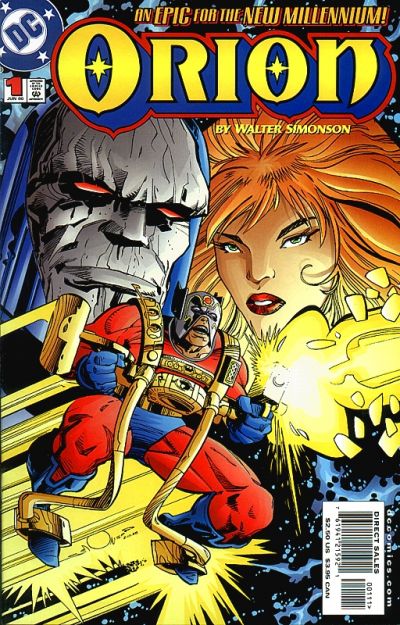

After Super Powers, the gods of New Genesis and Apokolips took their place as the official pantheon of the DC Universe, a kind of celestial board of directors to the traditional superheroes’ earthly workforce. It was a permanence that Kirby never intended, believing — as demonstrated by his walking away from the surefire Fantastic Four and Thor for the Fourth World itself — that achievements are meant to be surpassed and gods exist to be replaced. But for a long time it stuck, and as a consequence several revivals of the characters’ own series (including two or three New Gods from the ’70s onward, Jack Kirby’s Fourth World in the mid-’90s, and Orion in the early 2000s), though handled by some of the top talents in comics, have been hamstrung from the start by a requirement of narrative wheel-spinning. The open-endedness of Hunger Dogs was abused to keep the franchise going, and despite some pronounced permutations — including such bizarre variations as the portrayal of Anti-Life as a villainous organism and the collision of New Genesis and Apokolips to form a single, black-and-white-cookie world — each limited-run interpretation eventually lands the preexisting narrative back at Square One, so that there can be more stories, or remakes of the previous ones. Ironically, the mythos now lauded as one of the earliest attempts at a graphic novel and lamented for its incompletion may never be allowed to end.

End Part 3 — rejoin us tomorrow as Kirby gives way to the New Prophets in Part 4!

ALL INSTALLMENTS IN THIS SERIES

ALSO CHECK OUT: Jack Kirby as HiLo Hero by David Smay | Douglas Rushkoff on THE ETERNALS | John Hilgart on BLACK MAGIC | Gary Panter on DEMON | Dan Nadel on OMAC | Deb Chachra on CAPTAIN AMERICA | Mark Frauenfelder on KAMANDI | Jason Grote on MACHINE MAN | Ben Greenman on SANDMAN | Annie Nocenti on THE X-MEN | Greg Rowland on THE FANTASTIC FOUR | Joshua Glenn on TALES TO ASTONISH | Lynn Peril on YOUNG LOVE | Jim Shepard on STRANGE TALES | David Smay on MISTER MIRACLE | Joe Alterio on BLACK PANTHER | Sean Howe on THOR | Mark Newgarden on JIMMY OLSEN | Dean Haspiel on DEVIL DINOSAUR | Matthew Specktor on THE AVENGERS | Terese Svoboda on TALES OF SUSPENSE | Matthew Wells on THE NEW GODS | Toni Schlesinger on REAL CLUE | Josh Kramer on THE FOREVER PEOPLE | Glen David Gold on JOURNEY INTO MYSTERY | Douglas Wolk on 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY | Joshua Glenn on Kirby’s Radium Age Sci-Fi Influences | Chris Lanier on Kirby vs. Kubrick | Scott Edelman recalls when the FF walked among us | Adam McGovern is haunted by a panel from THE NEW GODS | Matt Seneca studies the sensuality of Kirby’s women | Btoom! Rob Steibel settles the Jack Kirby vs. Stan Lee question | Galactus Lives! Rob Steibel analyzes a single Kirby panel in six posts | Danny Fingeroth figgers out The Thing | Adam McGovern on four decades (so far) of Kirby’s “Fourth World” mythos | Jack Kirby: Anti-Fascist Pipe Smoker

ALSO ON HILOBROW: HiLobrow posts about comics and cartoonists, and science fiction

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2024 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE