King Goshawk (28)

By:

July 9, 2014

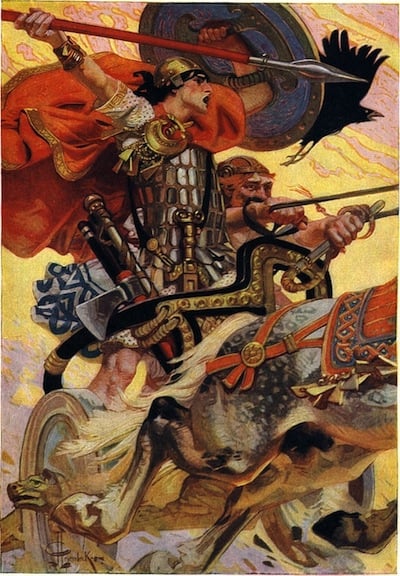

The 1926 satirical sf novel King Goshawk and the Birds, by Irish playwright and novelist Eimar O’Duffy, is set in a future world devastated by progress. When King Goshawk, the supreme ruler among a caste of “king capitalists,” buys up all the wildflowers and songbirds, an aghast Dublin philosopher travels via the astral plane to Tír na nÓg. First the mythical Irish hero Cúchulainn, then his son Cuanduine, travel to Earth in order to combat the king capitalists. Thirty-five years before the hero of Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, these well-meaning aliens discover that cultural forms and norms are the most effective barrier to social or economic revolution.

HILOBROW is pleased to serialize King Goshawk and the Birds, which has long been out of print, in its entirety. A new installment will appear each week.

Chapter 2: How the Two Lords made Propositions to Cuanduine

It was three days before the Lord Mammoth was able to find out where Cuanduine dwelt. When the information was brought to him, discarding his gorgeous raiment — for the making of which a hundred furry creatures had writhed in the cold steel jaws of traps — he donned a simple suit of plain grey tweed, and, accompanied by his faithful valet, took tram to Stoneybatter. He found the Philosopher alone in his room; for Cuanduine was out, walking gloomily on Merrion Strand by its sluggish waters.

“Good day, sir,” said the Lord Mammoth.

“Good day,” said the Philosopher.

“I had better introduce myself,” said the newsmonger. “I am Lord Mammoth.”

“And the other gentleman?” inquired the Philosopher, indicating the deaf and dumb valet who stood modestly behind.

“My attendant,” said Lord Mammoth. “I——”

“I meant his name,” said the Philosopher.

“His name? Ha, ha, ha,” laughed Lord Mammoth. “Don’t think I know it, now that I come to think of it. However, that’s not what I came about. You’re Mr. Cooney, I suppose?”

Before the Philosopher could answer, the door opened, and the prosperous figure of Lord Cumbersome came breezing in, almost upsetting the deaf and dumb valet, and completely ignoring Lord Mammoth, swept up to the Philosopher, clasped him warmly by both hands, and with radiant smile and treacly voice said: “My dear Mr. Considine, how do you do? I hardly expected to find you in. Pray excuse my enthusiasm” — shaking his hand with a fervour which the Philosopher found as embarrassing as it was uncomfortable — “but having read of your interesting discourses in the newspapers, I have been unable to rest until I should see you in the flesh.”

Here he was interrupted by the cold stern voice of Lord Mammoth: “I don’t know where you learnt your manners, Cumbersome, but I was engaged in conversation with Mr. Cooney when you came butting in.”

“My dear Mammoth, a thousand pardons,” said Lord Cumbersome, as with a start of surprise. “I entirely overlooked you. I apologise sincerely, and can only excuse myself on the ground that in the presence of such a man as Mr. Considine——”

“Gentlemen,” interrupted the Philosopher, “this is some strange mistake. My name is not Considine.”

“Cooney,” suggested Lord Mammoth.

“No,” said the Philosopher. “Murphy.”

“Then I owe you a most hearty apology,” said Lord Cumbersome winningly. “But is there not a man called Considine or some such name — a street preacher or something, with a mission of sorts — living somewhere near here?”

“The name is Cooney,” said Lord Mammoth sourly.

“If you mean Cuanduine,” said the Philosopher, “he lives here. But he is out at present, walking on Merrion Strand, with the weight of the world’s sorrow upon his shoulders.”

“I shall await his return,” said Lord Cumbersome, appropriating the only comfortable chair in the room.

“So shall I,” said Lord Mammoth, planting himself firmly on his own two legs.

“You’ve no objection, I hope,” said Lord Cumbersome pleasantly to the Philosopher; but the Philosopher did not hear him, being already absorbed in contemplation.

“Funny old bird,” observed Lord Cumbersome, but Lord Mammoth made no answer. Tired of standing, he directed his deaf and dumb valet to go down on hands and knees on the floor, and then sat on him. Lord Cumbersome’s eunuch presently made obeisance to his master, and began fanning him with a hand-buzzer of platinum and ivory; for the air of the Stoneybatter back street was oppressive.

Thus Cuanduine found them on his return. At his entry the Philosopher came out of his meditation; Lord Mammoth eagerly arose from the small of his underling’s back; and Lord Cumbersome followed suit from his chair. The Philosopher introduced them: “Lord Mammoth and Lord Cumbersome, news-purveyors. Cuanduine.”

“Delighted to meet you, sir,” said Lords Mammoth and Cumbersome in a breath.

“Why?” asked Cuanduine.

Lord Mammoth was taken aback, but Lord Cumbersome spoke suavely: “O come, sir. Can you ask such a question?”

“I have asked it,” said Cuanduine.

Here the Philosopher laughed, saying: “You see, gentlemen, it is no use offering polite commonplaces to Cuanduine. Answer his question and have done with it.”

“What question?” asked Lord Cumbersome.

“Why,” said the Philosopher.

“Why what?” said Lord Cumbersome.

“Better leave it at that,” the Philosopher said to Cuanduine. “These people’s memories are

rather short, and their words often meaningless. And now, gentlemen,” — turning to the paper merchants — “if you have anything to say, say it. If not, begone. Open your mouths wide, and speak distinctly.”

Now in all their lives these two lords of the linotype had never been spoken to in such terms as these, being used only to the baited breath of menials, and the oleaginous murmur of suppliants. Therefore the choleric Mammoth flushed with anger, and even the courteous Cumbersome was perceptibly annoyed; yet owing to the lack of experience aforesaid, they had no words for the occasion, so that near two minutes went by in silence while the flush faded from Lord Mammoth’s countenance, and the ruffling of Lord Cumbersome’s serenity sank into smoothness.

“Well — hm! hm! — quite so — yes,” said Lord Cumbersome. “Well, Mammoth, you were here first, and I’m in no hurry anyway, so I give place to you with the greatest pleasure in the world. Go ahead.”

“Thank you, Cumbersome,” said Lord Mammoth. “No doubt it would suit you excellently that I should make my offer first, and give you a chance to go one better: but I’m not having any. As far as I know, the side that wins the toss doesn’t have to go in first if it doesn’t like: it gets the option; and my option is to field until the wicket hardens.”

“How little you know me, Mammoth, and how little you know yourself,” sighed Lord Cumbersome. “I can wait here quite comfortably all day, and all night if necessary, whereas you must speak out or burst. Better do it now, and get it over,” and the languid forest-pulper reseated himself with a yawn.

Intolerably goaded, his rival addressed the waiting hero: “See here, Mr. Coondinner. Is this fair? I come here at a great deal of trouble and expense to make you an offer for our mutual advantage, and this fellow Cumbersome sets out to doublecross me. Well, he’s wasting his time. I’ll put my proposition now, and we can come to terms later. Meanwhile, whatever he offers, you can take it I’ll go ten per cent better, penny for penny. Is that clear?”

“Do you mean that you have come to offer me money?” asked Cuanduine.

“Exactly,” said Lord Mammoth.

“Then believe me, sir, I am deeply beholden to you, but I have some already.”

The Lord Mammoth was so astounded to see any one so receive an offer of money, that for full fifty seconds he was without breath for utterance. At last he said: “But good heavens, man, wouldn’t you like some more?”

“Why should I?” asked Cuanduine. “I have enough for my wants.”

“Now look here, young man,” expostulated Lord Mammoth, “you don’t know what you’re turning down. I’m putting anything from fifty to a hundred quid a week in your way. Just listen here. You come over to London with me to-morrow, and I’ll put you on our magazine staff right away. You’ll have an office all to yourself, and all you’ll have to do is to turn out three or four articles a day — say two to four hundred words apiece — just plain straightforward religious stuff, you know, with a bit of snap in it — nothing very deep, of course — look, here’s a sample of what I mean” — unfolding a copy of the Daily Record. “This is our special feature page. Snappy articles on all subjects, from Women to Religion. ‘Why Flappers Flirt,’ ‘The Habits of the Dandelion,’ ‘Love Jesus and Obey your Employer’; now that last is no good. It’s the effect we’re aiming at, of course, but it’s laid on too thick altogether. That’s because the fellow who’s doing it doesn’t really believe in it, and writes with his tongue in his cheek. Now you’re different. When I read that speech of yours at that funeral the other day, I saw that you’d got what few people have nowadays — Faith. You’ll write with conviction: and when I see a thing as rare as conviction on the market, I go for it straight and buy it, regardless of cost. Now this fellow I’ve got on the job has no convictions, and he doesn’t seem to know the difference between snap and blasphemy, so I want you to take his place. You’ve only got to write straight ahead exactly as you feel, provided of course that you keep within certain lines which I’ll mark out for you — ‘Be not solicitous what you shall eat or what you shall be paid,’ ‘Never mind the housing shortage: heaven is our home,’ ‘Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s,’ ‘Blessed are the poor in spirit,’ ‘The poor you have always with you,’ ‘Whatever may be said about the slums, the Son of Man had nowhere to lay his head,’ and so on — the sort of thing to cheer and elevate the poor, and generally comfort everybody. If you like to question the reality of Hell, do so by all means. I understand the latest notion is that it’s merely a sort of sense of spiritual loss. If you like to write that up, so much the better. Now what do you say to twenty quid a week for a start — with your chances, of course?”

“What an insufferably vulgar person you are, Mammoth,” drawled Lord Cumbersome, smothering a yawn. “Gentlemen, pray do not take this gentleman as representative of the newspaper world. Remember he wasn’t born to great wealth, but started as a reporter on four pounds a week.”

“The first Lord Cumbersome started as a printer’s devil,” snapped Lord Mammoth.

“True,” admitted Lord Cumbersome, smiling. “But the second and third were born Cumbersome. It only takes an accolade to make a peer, Mammoth; but it takes at least three generations to make a gentleman.”

“Never mind Cumbersome, gentlemen,” said Lord Mammoth. “He’s a wash-out. He hasn’t a third of my circulation — blue blood doesn’t flow as fast as red, you know. Ha! ha! Got you there, Cumbersome, didn’t I? That joke, gentlemen, is appearing in all my papers tomorrow, and the cream of it is that it was made by Cumbersome’s best humorist a few weeks before I bought him over. But let’s get back to business. What do you say to my offer, Mr. Cooney?”

“What does he want?” asked Cuanduine of the Philosopher.

“He wants you to write pious-sounding trash to keep people quiet while he makes.money; and he’ll pay you twenty pounds a week for doing it.”

The danger star glowed in Cuanduine’s eye at that, and the whirr of the gathering of the Bocanachs and Bananachs sounded in the distance like the first whisper of a coming storm.

The Philosopher, mindful of how they used to treat Cúchulainn in such crises, threw over him a jugful of water. I will not say that it boiled as it fell from his body (though indeed it did), for you would not believe me; but we have Lord Mammoth’s testimony that a splash of it scalded him through his trousers, and certain it is that two jugs more were needed to reduce the hero’s temperature to normal.

“You had better make no more such offers,” said the Philosopher to Lord Mammoth, “or the Water Trust will raise my rates.” But the Lord Mammoth was so awed by the miracle he had seen, and withal so dumfounded by the reception accorded, for the first time in his experience, to an offer of money, that there was no need for the warning. In fact it was only by strenuous application to the smelling-salts supplied to him by his deaf and dumb valet that he was enabled during the next five minutes to breathe at all.

Taking advantage of his silence, Lord Cumbersome arose from his chair and spoke.

“Gentlemen, I have not come here to — in his own eloquent and memorable phrase — double-cross a brother journalist in the speculative enterprise that has led him to the Emerald Isle. My sole object is to obtain for England the help and advice of one whom I unhesitatingly acclaim as a profound thinker and a legitimate claimant to the title of a truly Great Man. England, gentlemen, stands to-day on the brink of a volcano. All her most cherished ideals are in the melting-pot. Discontent is rampant among the lower classes——”

“Discontent with what?” asked Cuanduine.

“Goodness only knows,” said Lord Cumbersome. “Of course there’s the housing shortage, and the high cost of living, and the unemployment question, and the increased tax on milk, and so on — the usual, and I may say inevitable, concomitants of industrial civilisation: but, after all, when have we been without such troubles? Possibly the real cause is American dollars, as Lord Mammoth’s papers suggest; more possibly it is Japanese yen, as my own assert; or, for all I know, it may be Tcheko-Slovakian thingumabobs. But these are mere questions of academic interest. We are concerned to find a remedy rather than a cause; and that task I feel, sir, lies with you. Let me then, as an Englishman, who cannot watch unmoved the slow drift of his country to destruction, beg of you to come amongst us and apply your saving doctrines to our desperate case. Do not fear a repetition of the treatment that has been meted out to you here: you know a prophet is never honoured in his own country. Moreover, if I may say it without offence, Ireland has ever been intolerant of criticism. Now we English, though we cannot boast the dazzling qualities that distinguish Irishmen throughout the world, have certain solid characteristics which you admittedly lack. We are broadminded, tolerant, open to conviction. We are always ready to listen to new ideas, particularly when expounded by countrymen of your own. Did not our ancestors welcome the great Shaw to our midst, and though his every word was like a sharp stone flung at our vitals, did they not flock to his plays like sheep until they made him a millionaire, and praise and lionise him until he nearly burst with conceit? Mr. Coondinner, if you come to England, I can promise you that you will be received not with jeers and volleys of stones, but with rapt attention and showers of roses.”

“I will consider this,” said Cuanduine.

“Do so. And I will add one word more. I would not presume to ask you to become a paid contributor to my organs. But, to forward the good cause, they shall be always at your service. They have not the enormous circulation enjoyed by those controlled by Lord Mammoth; but they are papers of weight and standing, preserving the best traditions of English journalism, and read by the solid common-sense elements that are the backbone of the community. And now, sir,” concluded Lord Cumbersome, taking his hat from his eunuch, “I will not try to hurry you to a decision, but will take my leave, confident that the cry of England’s bewildered millions will not fall on deaf ears. Good day, gentlemen.”

He withdrew. After a decent interval the Lord Mammoth crept out also, followed by his deaf and dumb valet; whom later he cast into an oubliette, lest his affliction should not suffice to deter him from revealing the humiliation of his master which he had witnessed. As for Cuanduine, when the two Lords had left, he lay on his back on the floor and howled with laughter. What a shallow, flippant fellow he was to be so affected by the conversation of such shining examples of the successful life. Nevertheless he followed them soon after to England.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”