Phone Horror (8)

By:

July 3, 2014

[Eighth in a series of 10 posts on representations of the telephone as instrument of fear, conduit of spirits, and messenger of madness. Parts 1-4 were adapted from posts published at the blog The Face at the Window in 2005-06; parts 5-10 appear here for the first time.]

David Lynch’s Phone Horrifics

The ghostly contours of the techné beckon us to approach. We are drawn on by the rumor of what has happened to dialogue. It has been assassinated and resurrected in technology’s vampire.

— Avital Ronell, The Telephone Book (1989)

Among the most insistent elements in David Lynch’s emotional and physical apprehension of the world is his grungy fascination with hidden gears and works of all kinds. This manifests in a sound design as recognizable as a signature, wherein buildings wheeze with age and strain, floors and fixtures thrum with a terrified expectation; and where pipes, ducts, vents, and antique machines, sizzling wires and flickering lights reappear like revolving actors in an eternal repertory company.

We needn’t intellectualize this beyond stating what is intuitively plain and simple — that these tropes represent Lynch’s suspicion of what underlies human relationships whether social or personal, on however great or intimate a scale, from cityscape to psyche. As the pipes and wires hum behind walls or rise in some terribly organic-seeming way from the ground, his humans likewise sputter and flicker in their distortions, from a kind of cool, odd joke to a threat so silent and scary it’s like a hand scooping under your heart (the director’s encounter with “the Cowboy” in Mulholland Drive). You cannot quite say, finally, whether the pipes and wires are being anthropomorphized, or if the humans are being posited as flesh-covered machines, complex in their parts but simple in their functioning, and, like old buildings and underground works, full of rust and ghosts, the sediments of memory.

You’d expect, given all of this — or I would, anyway — that the telephone might be more of an element in Lynch’s atmospherics than it is. Oh, his movies are full of phone scenes, as Telma Sofia Moutinho’s piquant clip video “David Lynch on Telephone” demonstrates. But almost always in Lynch, phone talk is just that, and only that — people talking on phones. Sharing information; making a date; making a threat. Very little of a supernatural, inexplicable, or, even in the broadest terms, horrific nature occurs through the telephone in a Lynch film.

Very little — but some. In fact, when it comes to phone horror, Lynch has repaid in intensity all that might have been absent in consistency. In only two of his films do we find some horrific use of the phone; but both are uniquely rich, and both are unmistakable in employing the phone, of all worldly devices, as (to quote this series’ lede) instrument of fear, conduit of spirits, and messenger of madness. David Lynch may not use phone horror often, but he knows what it is.

*

Mulholland Drive (2001) is the weightier and more thoroughgoing of the two uses. Rewatching Lynch’s definitive film in light of our present concern, we find it is a tale framed by and infused with phone horror. After the initial car crash that sends an amnesiac Rita (Laura Elena Harring) stumbling down a hill from Mulholland Drive to Sunset Boulevard, where she will meet the newly arrived aspiring actress Betty (Naomi Watts), we see a series of sinister phone calls. The callers’ faces are not seen; they are all but created by the phones they use. The series ends on a ringing phone that goes unanswered: a phone whose ownership will be known only at the end.

Two men leave a Winkie’s diner to confront the horror lurking in the alley behind it — a horror embodying a nightmare experienced by one of the men — and there is a cut to a pay phone, the same phone Betty and Rita will later use to ask the police about the accident on Mulholland Drive. A low-life paid assassin kills a confederate to obtain a thick black book which the dead man has just claimed contains “the history of the world — in phone numbers.” When Betty and Rita call the number of a woman who might be Rita’s pre-amnesiac self, Betty says, “It’s strange to be calling yourself.” And Rita replies, “Maybe it’s not me.”

On its most obvious level, Mulholland Drive is the sternest warning ever issued to anyone who might seek fame in Hollywood, or even wonder if it is truly the Dantean pit of perfidy described by those who have felt shafted by its systems — its hidden pipes and wires. That obvious level is reinforced by the certain peripheral attention Lynch pays to common cautionary signage: “Do Not Enter”; “Stop”; “Fire.” But Hollywood the Destroyer is the more limited of the film’s layers, because how can most of us begin to refute, modify, or otherwise reinterpret it? Most of us have no direct experience with the movie business, and take all that we see or read of the town and its industry on a shared faith promulgated in a few famously acidulous works (The Last Tycoon, What Makes Sammy Run?, Sunset Boulevard, The Player).

The film’s phone horror plugs into this current insofar as Hollywood is famously a town ruled and run via telephone — the phone representing power, mystique, and the limitless promise or threat of the unseen. (Woody Allen called it a dog-eat-dog town; or even worse, “Dog doesn’t return other dog’s phone calls.”) But Mulholland Drive is great to the degree that it is about more than the parochial peeves of a filmmaker who hates Hollywood but can’t seem to leave it. Hollywood is better seen as a metaphor for Lynch’s sense of life at its most tragic — a smoggy sprawl of opportunity and chance, a glittering grid of impersonal treacheries and secret machinations, fueled by an unending supply of innocents who are left charred and wasted in the alleys behind Sunset Strip. What we see is Hollywood as a state of mind, but a mind deranged with obsession, despair, and disappointment. (“Now I’m in this…dream place,” Betty exults, long before any of us knows who she is, or what she really means by that.)

Phone lines connect the psychic stations of the protagonist’s journey, from the shadowy sanctum of the indescribable Mr. Roak to Diane picking up the phone we’d seen ringing in the earlier series of calls. Narratively, Muholland Drive is about the process by which the Watts character finds out what has happened to her. About a dead woman solving the mystery of her own murder; about a ghost discovering what she is. She does it by walking, wondering, dreaming — and calling herself on the phone.

I wondered this in an earlier post: “Do dead people feel fright? Do they cower, feel cold, lost, alone? Can a ghost fear itself?” In The Telephone Book, Avital Ronell as good as answers those questions by recovering “the original meaning of the word ‘ghost’ — a being terrified, beside himself, ek-static.” Take Mulholland Drive apart and put it together in this way, and it refracts as that kind of ghost story: a ghost calling herself on the phone, hearing what she sounded like before she died, and following the trail she left herself, back to the shuttered apartment and squalid bed where she ended her life.

*

The other Lynch film that makes notable use of phone horror is 1997’s Lost Highway, a badly underestimated movie — by myself, on first viewing, no less than anyone — and in some ways a dry run for Muholland Drive. It is an LA story, if not a Hollywood story; its opening is answered by its closing, each end meeting the other after a long, violent, discontinuous submersion in the head of a pathological obsessive. But Lost Highway has a suggestive seedy creepiness and combination of textures (from somnambulant near-silence to piercing aggression) unique in Lynch; it is more abstract, explosive, and extreme than his other films.

Also, technology plays a more direct role: the intercom, the video recorder, the automobile transmission. And the telephone. Lost Highway’s chief telephone scene is extolled as supremely unsettling even by those who don’t care for the work that embeds it. I will point out just one little thing about it; and then I will, as David Lynch so often does, leave the receiver dangling.

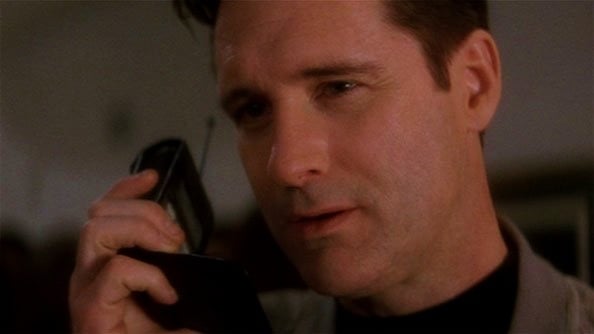

Once years ago, while nodding off in a Midwestern airport, I was running the scene in my head. Two men meet at a party. One of them, the lead character, a paranoid saxophonist played by Bill Pullman, is drinking at the bar. He sees a small, solemn man with powdered white face — identified as “The Mystery Man,” and portrayed by Robert Blake — staring at him from across the room.

Blake comes over. “We’ve met before, haven’t we?”

“I don’t think so. Where was it you think we met?”

“At your house. Don’t you remember?”

“No. No, I don’t. Are you sure?”

“Of course. As a matter of fact, I’m there right now.”

“What do you mean? You’re where right now?”

“At your house.”

“That’s fuckin’ crazy, man.”

Blake takes out a phone.

“Call me. Dial your number. Go ahead.”

Pullman takes the phone, enters the number, and listens. Blake’s voice comes through the receiver. “I told you I was here.”

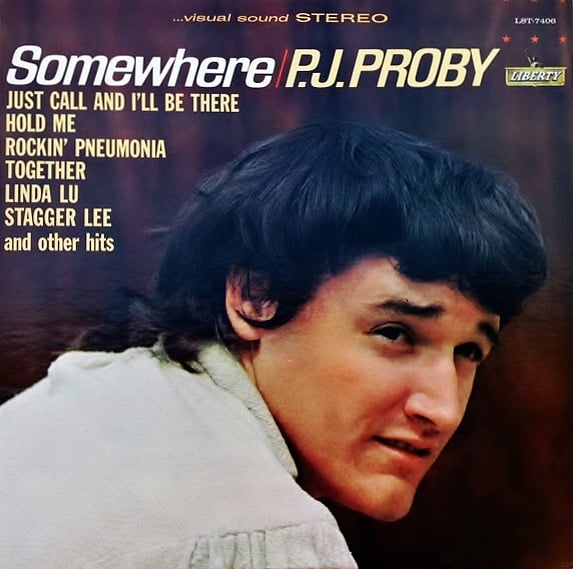

If you know the movie, you remember this scene. What you may not remember, or have quite noted at the time, is that although the soundtrack goes silent for this dialogue exchange, in the background up to that point plays a dance loop based on a light-jazz version of the 1968 Classics IV hit “Spooky.” The melody is easily recognized, the lyrics a clear enough analogue to the spookiness of the scene. But this instrumental remix, created by Barry Adamson and titled “Something Wicked This Way Comes,” contains a sample from another record, one heard just before Blake appears — a sighing female voice going sha-la-la-la to a sinister descending melody.

For almost a decade, from seeing the movie in a theater to sitting in this airport, I’d been taunted by that sample, trying to place where it had come from. Suddenly, my head drooping and consciousness drifting, it came to me: the sample was from a P.J. Proby record.

Eureka! To nail an elusive memory can be one of the most satisfying things in life. In the airport, I smiled sleepily. And what was that song’s title? It was one of the few things of Proby’s I’d ever cared for; I had it on mix tapes and iPods and I’d listened to it many times.

That’s when my head snapped up, and my eyes shot open.

The title of

“I’m there right now.”

the song was

“Call me.”

“Just Call and I’ll Be There.”

***

ALSO READ: Shocking Blocking: David Lynch’s Eraserhead

MORE HORROR ON HILOBROW: Early ’60s Horror, a series by David Smay | Phone Horror, a series by Devin McKinney | Philip Stone’s Hat-Trick | Shocking Blocking: Candyman | Shocking Blocking: A Bucket of Blood | Kenneth Anger | Sax Rohmer | August Derleth | Edgar Ulmer | Vincent Price | Max von Sydow | Lon Chaney Sr. | James Whale | Wes Craven | Roman Polanski | Ed Wood | John Carpenter | George A. Romero | David Cronenberg | Roger Corman | Georges Franju | Shirley Jackson | Jacques Tourneur | Ray Bradbury | Edgar Allan Poe | Algernon Blackwood | H.P. Lovecraft | Clark Ashton Smith | Gaston Leroux |