Phone Horror (2)

By:

June 11, 2014

[Second in a series of 10 posts on representations of the telephone as instrument of fear, conduit of spirits, and messenger of madness. Parts 1-4 are adapted from posts published at the blog The Face at the Window in 2005-06; parts 5-10 will appear here for the first time.]

“Night Call”

My phone fear goes back a long way. It has had many years to be eroded by the steady drip of reality, and the resultant rust of common sense. It is by no means a debilitating or even serious factor in my daily life, as it is for many. But I’m glad for the answering machine, which for me is like those heat sensors and motion detectors placed by ghost-hunters in dark rooms to record the passings of ambulatory spooks: blessedly inhuman, it performs a job I’m disinclined to do.

Memories of early telephonic trauma are vague, distant, yet present: a run of obscene phone calls at an impressionable age, creepy pranksters and heavy breathers intruding on my wee hours. Visit these upon a latch-key adolescent in an empty house—a kid already generously endowed with morbid imagination and a terror of being singled out, by anyone, for any reason—and you have the basis of a mild, albeit enduring, case of phone fear.

Evidence suggests I’m not alone in this. Horror writers have long intuited the telephone as a modern conduit of primal fear: how many times has it been the fulcrum of fright in movies, TV shows, novels, and short stories? I began wondering this in earnest after a viewing of the Twilight Zone episode “Night Call,” starring Gladys Cooper, directed by the estimable Jacques Tourneur (Cat People, Out of the Past, Night of the Demon), and scripted by Richard Matheson from his 1953 short story, “Sorry, Right Number.”

Though I—like you, no doubt—have been watching Zone reruns since approximately forever, I’d never caught this episode, which premiered the night of Friday, February 7, 1964. Yet it uncurled like an old dream revisited. An elderly woman, whose only companion is the paid nurse who looks after her during the day, tosses and turns over a sleepless night. The looming, windswept tree outside lashes shadows over her bed. The invalid woman is lonesome, restless, gripped by an ambiguous fear.

Suddenly the phone rings, exploding the silence. She answers: nothing from the other end but a distant, unvarying crackle.

Another call the next day. More crackling. The nurse is urged to the receiver; she hears nothing. Late that night, the third call comes. This time a voice emerges, a male voice, peculiarly hollow and lifeless. “Where are you?” it asks. “I want to talk to you.” Whereupon the old woman quite reasonably screams, “Leave me alone!”

She calls the phone company to report the harassment, and is told that a wire is down somewhere out in the country. It happens to be lying across the grave of her husband—who has been dead for years, killed in the car crash that made an invalid of his wife. Putting two and two together—And getting a sum that exists nowhere … but in the Twilight Zone, Rod Serling might have said—the woman realizes she has heard her husband’s voice from beyond.

Overjoyed at the surcease of her loneliness, she excitedly utters his name into the telephone receiver.

“You told me to leave you alone,” the voice says. “And I always do what you say.” Click.

Harsh, even for a Twilight Zone twist.

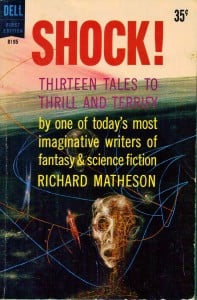

The day after seeing “Night Call,” I climbed to the upper shelf where I store my modest collection of vintage pulp paperbacks. I checked the Matheson titles. There it was, in the 1961 collection Shock!: the original story, its title changed to “Long Distance Call.” I read it. It wasn’t brilliant. Matheson’s writing was less vivid than usual, in fact was barely serviceable. (Even at his best, he was never the equal of Charles Beaumont, who along with Matheson and Rod Serling himself completed the triptych of top Zone writers.) Yet “Long Distance Call” was, at least in terms of plotting and denouement, far more alienating than the TV version—almost existential in its oafish exposition and dull description, like Kafka from the pen of an American primitive. There was no poignancy imparted to the ghost calls, nor any connubial back-story to humanize them. No Grand Guignol, no “Boo!” moves; only a nonplussed regard of the unaccountable.

The calls themselves are the same in story and teleplay: the ring in the dark of night; the initial maddening crackle; the voice from the grave. Only, in the story, it’s not the woman’s husband calling. In fact, you aren’t told who or what is at the other end. But the story ends with the words, “I’ll be right over.”

The ring of the phone can strike terror in me, but actually the ring is only prelude. What really terrifies me is the possibility of hearing those words: “I’ll be right over.” It may have something to do with the common nightmare of being pursued by a malign figure; and it may be that all such fears spring from the same psychic seed, which is a basic fear of other people. Not their actions so much as their mere presence; not of being hurt by them, but of having to interact with them. The supernatural element of horror literature is a displacement, I’m certain, of something that basic, that deeply rooted and ineradicable, and those of us who seek terror in and from storytelling forms are indulging that fear—reliving it compulsively.

But I don’t care to waste a good scare on any merely psychological, reductively flesh-bound explanation. Those phone calls from beyond? They weren’t in the old woman’s head. They were from beyond.

***

MORE HORROR ON HILOBROW: Early ’60s Horror, a series by David Smay | Phone Horror, a series by Devin McKinney | Philip Stone’s Hat-Trick | Shocking Blocking: Candyman | Shocking Blocking: A Bucket of Blood | Kenneth Anger | Sax Rohmer | August Derleth | Edgar Ulmer | Vincent Price | Max von Sydow | Lon Chaney Sr. | James Whale | Wes Craven | Roman Polanski | Ed Wood | John Carpenter | George A. Romero | David Cronenberg | Roger Corman | Georges Franju | Shirley Jackson | Jacques Tourneur | Ray Bradbury | Edgar Allan Poe | Algernon Blackwood | H.P. Lovecraft | Clark Ashton Smith | Gaston Leroux |