Phone Horror (1)

By:

June 8, 2014

[First in a series of 10 posts on representations of the telephone as instrument of fear, conduit of spirits, and messenger of madness. Parts 1-4 are adapted from posts published at the blog The Face at the Window in 2005–06; parts 5–10 will appear here for the first time.]

Foreword: 2014

I began collecting occurrences of, and writing notes on, phone horror in books, movies, TV shows, etc., about a decade ago. Our relationship with that device was already changing, but within a few years the science and practice of telephony would turn a corner, break into a sprint (no pun intended), and never look back.

Unless I’m blanking on the obvious, there is no tool whose fundamental user interface has been transformed so completely by digital technology. Cars basically drive as they always did. The iPod is a souped-up Walkman. The computer keyboard follows the eternal QWERTY of the manual typewriter. But the phone is not even close to what it used to be, nor is it yet quite conceivable that its pre-millennial form will make a comeback—as have, for instance, vinyl records, the compact disc having failed dismally, in the fullness of time, to usurp its mythic progenitor.

Once upon a time, you couldn’t fit a phone in your pocket or purse. You couldn’t use it to play music, take pictures, shoot video, or check the Internet. You couldn’t select your ringtone or customize your desktop image—because your phone didn’t have a desktop, and its tone was predetermined, for many decades, by Ma Bell, and then, after deregulation, by the manufacturers of budget-priced, cheaply-made phone sets. You could, starting in the late 1980s, speed-dial the last number you entered, and program up to seven or eight others; but your phone probably still needed a wire to work, and woe unto you if your emergency situation didn’t occur in close proximity to a wall jack.

If the phone rang and you were in another room, you had to come running: in that immediate sense, and in a way that now seems comical, your phone controlled you. And before the ‘90s, there was no caller ID, an inconvenience which ensured, for that benighted first century-plus of the instrument’s analog existence, the first premise of phone horror—that you could never know for certain whose voice, or what sound, would issue from the other end of that raised receiver.

What kind of evil might the telephone service, were it sentient? What spectral forces might it give ingress, were it accessible to the unseen? Questions like these made it easy, for those with too much imagination, to be inordinately nervous around the phone.

But that was once upon a time. Few of us still feel that way about the phone. So this series of posts will, to some degree, be an exercise in nostalgia—a look back upon dark places now awash in digital light; places we will likely never see again, except in our memories, and in those books, movies, TV shows, etc., that call to us from an earlier world. But I ask you to join me in taking that backward look, partly because you’re probably, like me, old enough to remember quite well—in fact, with utter clarity—the specific physical, audial, and emotional sensations associated with the telephone as it used to be; and partly because indexing the changes between eras of our lives, measuring the chasm between Then and Now, is one way we assess ourselves over time. Getting older, I derive entertainment and edification from renewing my contact with things that entertained and edified me as a child, preteen, and teenager. Almost all of us do that. It’s nostalgia, yes, and escape from adult worry. But it’s also a drawing of lifelines between marks that were made upon me then and marks that are still there today. Looking back at what has changed in my world is a way of discovering what remains unchanged in myself.

“Phone Call”

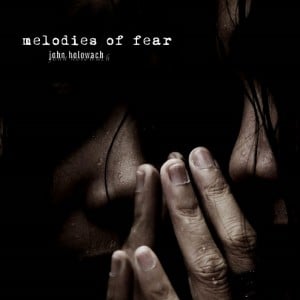

John Holowach’s Melodies of Fear (2005) is an album-length collection of MP3s available, like much of the Ohio-based composer’s other work, at the Internet Archive. Stumbling across it by not-quite-chance, I was intrigued by the come-on: “A side project/album for musician/samplist John Holowach, this one detailing various new and old songs and music tailored to horror and fear.”

It turns out that, despite promising titles like “Shadows on the Walls,” “Chant for the Dead,” and “Tuned Piano for a Haunted Room,” Melodies of Fear is more doom-drenched than directly scary, some tracks sounding like Trent Reznor on a mild upper, others like Julee Cruise remixed for the dance floor. But one track hit me where I dream, choked me where I breathe. It’s something I’ll always come back to, the way I come back to Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, Charles Beaumont’s “The Howling Man,” or Lord Bulwer-Lytton’s “The Haunted and the Haunters.” It’s titled “Phone Call.”

I first experienced it while sitting at my computer on the far side of midnight, earphones wrapped around my head. For the 90 seconds or so that it lasted, I kept glancing behind me to make sure no one was there. My wife was sleeping in the bedroom; if she’d awakened just then, come out to say hi, and innocently tapped me on the shoulder, I might have fainted.

“Phone Call” sounds like this:

Dial tone, numbers laboriously punched in, and then a succession of terrified voices—all of them distinct but joined in a continuous flow, one mutating into the next, a 35-year-old man into a 12-year-old girl. There is a rush of gasping, cascade of breathing, whispering of fragments all pregnant with dread: “Don’t … don’t leave me here.” “I’m not by myself.” Throughout, the echoed barking of distant dogs. (Is someone out there?) Then the voices are blanketed by silence. Then the line goes dead.

It seems so obvious. It’s the stuff of so many movies, including some notably cheesy ones. But composed as pure sound, untethered to all the surface or subliminal detail inherent in a filmed image (an actor’s unique face, the clichéd creep through an empty house, the reassuring semiotics of slasher horror), the effect of “Phone Call” is not obvious at all. There is something crucial about the electronic aspect: the mechanical phone music, the vocal distortion of fiber optics, the anonymity of the wire and implied death of the broken connection. A little universe of horrible implications blooms within a plastic box of wire and steel, a box no larger or prepossessing than the smooth blue shiny one that holds the secrets of Mulholland Drive.

“Phone Call” is every bit the product of this age of globe-spanning cables, sizzling connections, and invisible filaments. Yet it’s as visceral as our most ancient superstition—that of a devouring darkness, a soul-snatching unknown lying just outside the cave of our certainties.

***

MORE HORROR ON HILOBROW: Early ’60s Horror, a series by David Smay | Phone Horror, a series by Devin McKinney | Philip Stone’s Hat-Trick | Shocking Blocking: Candyman | Shocking Blocking: A Bucket of Blood | Kenneth Anger | Sax Rohmer | August Derleth | Edgar Ulmer | Vincent Price | Max von Sydow | Lon Chaney Sr. | James Whale | Wes Craven | Roman Polanski | Ed Wood | John Carpenter | George A. Romero | David Cronenberg | Roger Corman | Georges Franju | Shirley Jackson | Jacques Tourneur | Ray Bradbury | Edgar Allan Poe | Algernon Blackwood | H.P. Lovecraft | Clark Ashton Smith | Gaston Leroux |