King Goshawk (5)

By:

January 28, 2014

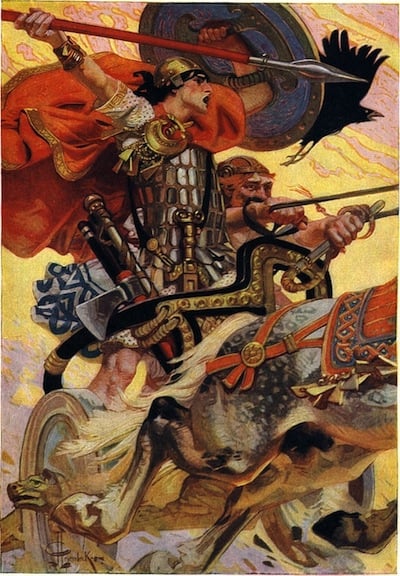

The 1926 satirical sf novel King Goshawk and the Birds, by Irish playwright and novelist Eimar O’Duffy, is set in a future world devastated by progress. When King Goshawk, the supreme ruler among a caste of “king capitalists,” buys up all the wildflowers and songbirds, an aghast Dublin philosopher travels via the astral plane to Tír na nÓg. First the mythical Irish hero Cúchulainn, then his son Cuanduine, travel to Earth in order to combat the king capitalists. Thirty-five years before the hero of Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, these well-meaning aliens discover that cultural forms and norms are the most effective barrier to social or economic revolution.

HILOBROW is pleased to serialize King Goshawk and the Birds, which has long been out of print, in its entirety. A new installment will appear each week.

Chapter 5: How the Philosopher borrowed a Body for Cúchulainn

So the Philosopher’s mind returned to him in the little room in the back lane off Stoneybatter; and having rubbed his natural eyes he saw the spirit of Cúchulainn standing before him, glorious and resplendent as a flame in a dark place, as a fountain among stagnant waters.

“Welcome to Earth and to my humble abode,” said the Philosopher. “And pray pardon me if I leave you for a moment: for I must find you a body, in order that you may go inconspicuously among men, and see for yourself the folly and wickedness from which you would redeem them.” And at that he took himself off, leaving the hero gazing in bewilderment at the strange habitation of the heir of the ages.

Now there was a man dwelling on the same floor as the Philosopher who thought life was not worth living; for he had to spend most of it making up pounds and half-pounds of tea, sugar, flour, butter, cheese, bacon, sausages, and the like into parcels and being polite to the fools that bought them; and he had to subsist himself on the same commodities, which he hated with the same intensity and for the same reason as the slaves who built the Pyramids must have hated the architecture of Ancient Egypt. He felt that it was no life for a man to rise in the morning before the sun had taken the chill from the air, to be at every one’s beck and call during the best hours of the day, and not to be free till its tag end when there was nothing to do but sit in a stuffy picture-house puffing fags. Of course there were also Saturday afternoons and Sundays: but what could you do with a half-day beyond killing time at the pictures or a football match? and most of a Sunday was gone by the time you had heard Mass and finished dinner, and the picture-houses didn’t open till eight o’clock. Oh, it was a hard life and a dull life to be doomed to, very different from the life of his dreams. He would have liked to be rich, to be exquisitely dressed, to live in a gorgeous house, to have abundance of leisure, to have silent, smoothly-gliding servants and automobiles always at his command, to be loved and won by glorious shining women — in short, to live like the heroes of his favourite film dramas. Instead of that he had to work, to obey orders, to loiter aimlessly between whiles, to wear cheap ready-made suits, to dodge other people’s motors and serve their servants with sugar and sausages, and every hour of the day to be tempted by the sight of women customers and passers-by with pretty ankles and swelling hips and bosoms, that would stir up hot tormenting passions which he could only satisfy by risking damnation to eternal brimstone, or else by getting married — which he couldn’t afford, and besides the girl he was walking out with was no great marvel, with her pale lips and her flat chest and her thin legs that didn’t properly fill her stockings. Oh, a very dull life, thought Mr. Robert Emmett Aloysius O’Kennedy.

It was to this man that the Philosopher came seeking the loan of a body. He was standing before his mirror wondering whether he ought to wash his neck that morning when he heard the Philosopher’s knock.

“Come in and sit down,” he said hospitably, for he liked the Philosopher, thinking him an amusing old ass. “You don’t mind if I go on washing?” he added. “Because I’ll be late if I don’t,” and, having decided to spare his neck for yet another day, he began vigorously to sponge his face.

“You told me the other day,” said the Philosopher, “that you didn’t consider life worth living.”

“I did,” said Mr. O’Kennedy.

“Do you still think the same?” asked the Philosopher.

“I do,” said Mr. O’Kennedy, and began to dry his face in an exceedingly dirty towel.

“Would you like to quit it for a time?” asked the Philosopher.

“I’d like to quit it for good,” said Mr. O’Kennedy emphatically.

“For ever is a long time,” said the Philosopher. “But I think we could manage a month.”

Mr. O’Kennedy would have winked here if there had been anybody to wink at. The old boy was certainly more cracked than usual this morning.

“What is your body worth?” asked the Philosopher.

“Couldn’t be sure,” said Mr. O’Kennedy. “The boss pays me three quid a week for the use of it, but I think he includes my soul in the bargain.”

“Your body is all I want,” said the Philosopher. “What do you say to two pounds ten? And while I’m using it your soul can go off to heaven for a rest.”

“Done,” said Mr. O’Kennedy, who thought he had a yarn that would keep his friends in stitches for a week.

Then the Philosopher put Mr. O’Kennedy sitting in a chair; and he made three passes with his hands; at which the body of the young man became fixed and immovable, and his soul was filled with fear.

“Stop!” he cried. “You are killing me.”

“You said that was what you wanted,” said the Philosopher.

“I didn’t mean it,” said Mr. O’Kennedy.

Then the Philosopher made three more passes; and the soul of the young man departed from him, and went wandering into space. But the Philisopher took his body, and stripped it, and washed it thoroughly, and brought it to his own room, where he set it down before Cúchulainn, saying:

“Come, now. Here is a body: a poor thing; a pitiful thing; not too well made, and somewhat marred in use; but still a semblable human body. Put it on.”

Cúchulainn looked at the body and did not like it at all; for it was meanly shaped, without sign of beauty or strength. The muscles were small and flabby; the spine curved; the feet distorted fantastically by ill-fitting boots: a body unsuited to a hero. Cúchulainn picked it up distastefully, as one might handle another’s soiled combinations. Then he gave it a shake and clasped it to him; the spirit seemed to melt and blend with the body; and presently the heart of Robert Emmett Aloysius O’Kennedy began to beat, his lungs to breathe, his eyes to open, and his limbs to stretch themselves, as if the soul within were testing its new tenement. For some minutes after the figure stood motionless with introspective eyes, like one in contemplation. Then came a lightning change: convulsions seized upon the body of Mr. O’Kennedy, and in an instant Cúchulainn had cast it from him with a cry of horror.

“O pitiful brain of man,” he said. “What fears, what habits, what ordinances, what prohibitions have stamped you slave. I thought just now that I was in a very sweat of terror of some dreadful being named the Boss, who held over me mysterious powers, and from whom I anticipated chastisement if I were late in his service to-day, as I most assuredly expected to be. At the same time I felt a certain small satisfaction in remembering that yesterday I had done him some underhand injury which he would be unable to trace to my account. It was but a small weed of joy in a forest of fears. I had a fear that a man I knew might have heard that I had spoken ill of him that day; and another fear that a man I had lied to might find me out. I had also a fear that my clothes were not quite the same as were worn by every one else, and a fear of what all the people I knew might be saying or thinking of me at the moment. Then there was in me a fear that had been inspired some time ago by a play I had seen, which made me seem to myself a mean, stupid, and malicious creature; and of that fear there was born in me a hatred of the play and of the man who wrote it. I hated him for using the theatre, where I went to enjoy myself, as a means of making me hate myself. And that recalled to my memory the worst fear of all those that beset me. For in the same theatre a few days before I had watched some women dancing, and my eyes had feasted on the roundness of their limbs, and my body had been bathed in warm desires. For that sin I was damned eternally to a pit of flame unless I should repent and confess. I was afraid to confess, for fear of what the druid should think of me: and I was afraid not to confess for fear of the pit of flame. Then I began to make excuses for myself, saying that I had not looked very long and that after all there had not been much to see, so that I had not sinned mortally, and had earned only some temporary fire. But I could not make myself feel quite sure of that; nor could I decide whether I was more afraid of the confession or the pit of fire. Then I began to wonder whether there was really a God or a pit of fire at all. But I dared not let myself think of that, lest I should be struck dead and buried in the pit of fire forthwith; whereupon I — even I, Cúchulainn — was seized with a loathsome terror, to escape which I cast the foul body from me. And let you, O Philosopher, remove it now; for I swear by the sunlight of Tír na nÓg that I will not take to me such a horror again.”

“That is not spoken like Cúchulainn,” replied the Philosopher, “who in the olden times, when he was a man and a hero, was never known to look back from a task that he had once undertaken. It is clear, however, that the spirit is affected by the conditions of the somatic substrate on which it depends for expression, so I will clean it up and let you try it on again.”

So saying the Philosopher took scalpel and forceps, and, having opened the skull of Robert Emmett Aloysius O’Kennedy, and carefully reflected the membranes, he exposed the brain to the full glare of the morning sun. Then in a bottle he compounded a lotion of carbolic acid, cold horse sense, and common soap, with which he thoroughly scoured and irrigated both the psychical centres of the cerebral cortex and the association fibres connecting them with each other and with the sensory centres: for, as Halliburton or another hath it, Nihil est in intellectu quod non prius in sensu fuerit. After this operation, Cúchulainn entered again into the body, which straightway began to glow with a divine beauty. The skin glistened like white satin; great muscles swelled and rippled beneath it; the chest expanded to a third as much again as it was; the back straightened like a spring released; the eyes flashed fire; and the sheepish countenance of Robert Emmett Aloysius O’Kennedy shone like that of a hero in his feats. Again Cúchulainn began to test the strength of his borrowed frame, stretching the arms above his head, expanding the chest, stamping the feet on the ground: until at last the Philosopher cried:

“Hold now! Enough! Do you not remember all the war-chariots and the swords and spears you broke in the testing the day you first took arms and went foraying against the Dun of Nechtan’s sons? This bag of bones is too frail for such experimenting, and if you wreck it I cannot get you another. Besides it is only hired by the week.”

Then sounded the voice of Cúchulainn from the vocal chords of Robert Emmett Aloysius O’Kennedy like a symphony of Beethoven from the brass trumpet of a cheap gramophone, saying: “Excellent advice, O Sage, and none too soon, for already I feel my shoulders crack. I will forbear in other respects, but the ghosts of my seven toes are most uncomfortably crammed into the warped and etiolated extremities of this starveling here, so that I seem to tread on dried peas: therefore stretch them I must.” So he sat down, and began bunching his toes as one might do to expand a shrunken stocking; and with the effort the metatarsal bones straightened out, the phalanges uncurled, a shower of corns and bunions fell on the floor, and the two feet, which had hitherto looked more like the bleached rhizomes of some unknown plant than any part of an intelligent animal, assumed a healthy shape and hue, and heroic proportions. Even so Cúchulainn was not yet comfortable in his corporeal tenement, but presently said to the Philosopher, very wry in the face: “I fear I can never wed myself peaceably to this flesh. Lo, I have here” — pointing to his belly — “a most woeful and disturbing sensation, as of a griping emptiness, and unless it is soon relieved I will abandon this carnal vesture yet again and return to Tír na nÓg.”

“That is most unfortunate,” said the Philosopher. “I had hoped you would be free of the human frailties and the physical needs which hamper us. This pain you feel is called hunger, and it is the prick of the goad with which King Flesh reminds us that we are his slaves, forcing us to cram ourselves with bread and meat, which we metabolise into energy, which we must use to procure more bread and meat, thus remaining in a vicious circle of uselessness, eating to live and living to eat, instead of turning our minds to the pursuit of wisdom. And now that I come to think of it, I am hungry myself, and no wonder, for I have forgotten how long it is since my last meal. Have patience now, and in a moment both our pangs shall be assuaged.”

The Philosopher then went out and in a shop at the corner of the street he bought a loaf of bread, a piece of cheese, and a quart of milk; on which provender he and Cúchulainn fared right joyously, charging their batteries with peptone and the other approved albuminoids, not forgetting a due proportion of vitamines as prescribed by the medical columns of the Sunday papers. Believe me, bread and cheese and milk is the best food in the world for hungry men, when you can trust your dairyman and beer is under a ban: the proof of which is that when Cúchulainn had finished he rose from his chair, and, stretching himself, put a foot through the floor and both hands through the ceiling.

“Steady!” said the Philosopher. “This is not Bricriu’s Palace. It is time your limbs were fettered with the garments of civilised society.” So saying, he took out some spare ones of his own and showed Cúchulainn how to put them on. Be sure that Cúchulainn in donning the trousers and tucking in the shirt showed no more grace or dignity than your mortal man—poet, priest, politician, soldier, average fool, or father of ten. I wish, indeed, that all men who hold position or notoriety could be compelled to put on their trousers publicly at least once a year: by which means we should rid ourselves of a vast quantity of that humbug and hero-worship which make the world intolerable for honest and self-reliant men. For as the proverb says, no man is a hero to his valet: the reason being that the valet sees the hero getting into his trousers.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”