Theodore Savage (23)

By:

August 12, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the twenty-third installment of our serialization of Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (also known as Lest Ye Die). New installments will appear each Monday for 25 weeks.

When war breaks out in Europe — war which aims successfully to displace entire populations — British civilization collapses utterly and overnight. The ironically named Theodore Savage, an educated and dissatisfied idler, must learn to survive by his wits in the new England, where 20th-century science, technology, and culture are regarded with superstitious awe and terror.

The book — by a writer best known today for her suffragist plays, treatises, and activism — was published in 1922. In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish it in a gorgeous paperback edition, with an Introduction by Gary Panter.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

“No,” Theodore told him, “you wouldn’t have killed them…. One of them said the same thing to me — one of the wicked ones. He said we should have stamped out the race of them. Afterwards I knew he was right, but at the time I didn’t understand. I couldn’t. I heard what he said, but the words had no real meaning for me.”

He saw something that was almost contempt in his son’s eyes and took the grubby face between his hands.

“That same wicked man — who was also very wise — told me something else that is as true for you as it was for me; he said that we never know anything except through our own experience. I might tell you that the sun is warm or the water is cold, but if you had never felt the heat of the sun or the cold of the water you would not know what I meant. And it was like that with us; there were always some few who understood that knowledge was a flame that, in the end, would burn us — but the rest of us couldn’t even try to save ourselves until after we were burned.”

He stroked the grubby face as he released it.

“That’s the Law, son; and all that matters you’ll learn that way. That way and no other — just as we did.”

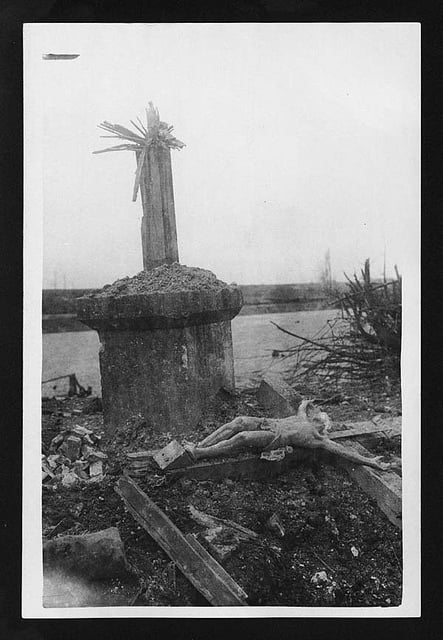

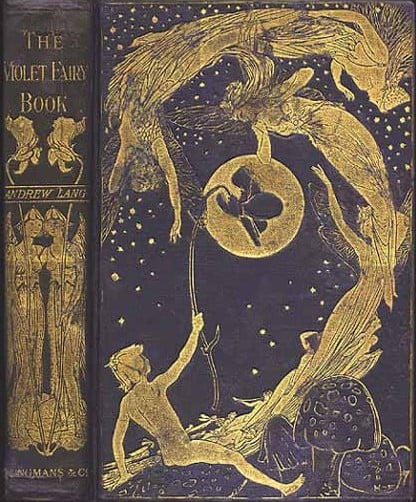

In time he found himself recalling, with strange interest, the fairy-tales of his childhood; he spent long hours re-weaving and piecing them together, searching his memory for half-remembered fragments of what had once seemed fantasy or nonsense invented for the nursery. The hobgoblins and heroes of his nursery days were transformed and made suddenly possible; looking through the mind of a new generation, he saw that they might have been as human and prosaic as himself. More — he came to know that he and his commonplace, civilized contemporaries would be the heroes and hobgoblins of the future.

The process, the odd transformation, would be simple as it was inevitable. It was forbidden, by the spirit and letter of the Vow, to awaken youthful curiosity concerning the past — youthful curiosity whose end might be youthful experiment; but women, in spite of all vows and prohibitions, would gossip to each other of their memories. While they talked their children would listen, open-eyed and puzzled; and when a youngster demanded the meaning of an unfamiliar term or impossible happening, the explanation, as a matter of course, took the form of analogy, of comparison with the known and familiar. The aeroplane was a bird extinct and monstrous — larger, many times larger, than the flapping heron or the owl; the bomb was more dreadful than a lightning stroke; the tram, train or motor a gigantic wheelbarrow that ran without man or beast to drag it…. The ignorance of science of those who told, the yet greater ignorance of those who heard, resulted, inevitably, before many years had passed, in myth and religious legend — an outwardly fantastic statement of actual fact and truth. The children, piecing together their fragments of incomprehensible information, made their own image of the past — to be handed on later to their sons; an image of a world fantastic, enchanted and amazing, destroyed, as a judgment for sin against God, by strange, fire-breathing beasts and bolts from heaven. A world of gigantic fauna and bewitched chariots; likewise of sorcerers, their masters — whom God and the righteous had exterminated…. So Theodore realized — as his children grew and he heard them talk — must a race that knew nothing of science explain the dead wonders of science; from the message that flashes round the world in seconds to the petrol-engine and the magic slumber of chloroform. That which is outside the power and beyond the understanding of man has always been denounced as magic; and steam, electricity, chemical action, were outside the power and beyond the understanding of men born after the Ruin. In default of understanding they must needs fall back on a wizardry known to their fathers; thus he and his contemporaries to their children’s children would be semi-supernatural beings, fit comrades of Sindbad, of Perseus, or the Quatre Fils Aymon: giants with great voices that called to each other across continents and vasty deeps; possessors of seven-league boots, magic steeds and flying carpets — of all the stock-in-trade of the fairy-tale…. Belief in the demi-god was a natural growth and product of the world wherein his son grew to manhood.

Given time and black ignorance of mechanics and science, and the engineer would be promoted to a giant or demi-god; who, by virtue of a strength that was more than human, dammed rivers, drained bogs and pierced mountains. “As it was in the beginning, is now and ever shall be”— and always in the past there had been giants. Titans — and Hercules, removing mighty obstacles and cleansing the stables of Augeas. He came to understand that all wonders were facts misinterpreted and that (given time and ignorance) a post-office underling, tapping out his Morse code, might be seen as a geni or an Oberon — the absolute master of obedient sprites who could lay their girdles round the earth; and he pictured a college-bred, sober-suited Hercules planning his Labours in the office of a limited company — jotting down figures, estimating costs and scanning the reports of geologists. Figures and reports, like his tunnels and dams, would pass into the limbo of science forgotten and forbidden, but the memory of his labours, his defiance of brute nature, would live on as the story of a demi-god; and the childhood that was barbarism would explain his achievements by a giant strength that could tear down trees and move mountains.

The idea took fast root and grew in him — the idea of a world that, time and again, had returned to the helplessness of childhood. He saw science as the burden that, time and again, the race found intolerable; as Dead-Sea fruit that turned to ashes in the mouth, as riches that humanity strove for, attained and renounced — renounced because it dared not keep them. In his hours of dreaming he made fairies and demi-gods out of dapper little sedentary persons, the senders of forgotten telegrams, with forgotten engines — motor-cars and aeroplanes — at their insignificant command ; and once, in the night, when Ada snored beside him, he asked himself if Lucifer, Son of the Morning — Lucifer who strove with his God and was worsted — were more, in his beginnings, than a scientist intent on his work? A chemist, a spectacled professor, resplendent only in degrees and learning? An Archfiend of Knowledge who had sinned against God in the secret places of a laboratory and not upon the shining plains of Heaven? And whom ignorance and time had glorified into the Tempter, the Evil One — setting him magnificently in the flaming Hell which he and his like, by their skill and patience, had created and let loose upon man?… This, at least, was certain; that in years to come and under other names, his children’s children would re-tell the story of Lucifer, Son of the Morning; the Enemy of Man who was flung out of Heaven because, in his overweening vanity, he encroached on the power of a God.

It was the new world that taught him that man invents nothing, is incapable of pure invention; that what seem his wildest, most fantastic imaginings are no more than ineffective, distorted attempts to set down a half-forgotten experience. What had once appeared prophecies he saw to be memories; the Day of Judgment, when the heavens should flame and men call upon the rocks to cover them, belonged to the past before it belonged to the future. The forecast of its terrors was possible only to a people that had known them as realities; a people troubled by a dim race-memory of the conquest of the air and catastrophe hurled from the skies….

So, at least, his children taught him to believe.

With years and rough husbandry the resources of the tribe were augmented and it emerged from its first starved misery; more land was brought under cultivation and, as tillage improved and better crops were raised, the little community was less dependent on the haphazard luck of its fishing and snaring and lived further from the line of utter want. While, save in bad seasons, the inter-tribal raiding that was caused by sheer starvation was less frequent. Even so, strife was frequent enough — small intermittent feud that flared now and again into savagery; the desire of a growing community to extend its hunting-grounds at the expense of a neighbour meant, almost inevitably, appeal to the right of the strongest. Other quarrels had their origin in the border inroads and reprisals of poachers or a barbaric setting of the eternal story that was old when Helen launched a thousand ships.

With husbandry, even rough husbandry, came the small beginnings of commerce, the barter and exchange of one man’s superfluities for the produce of another man’s fields. Cold and nakedness stimulated ingenuity in the matter of clothing, even in a society whose original members had in large part been bred to depend in all things on the aid of the machine and to earn a livelihood by the performance of one action only — the tending of one lathe, the accomplishment of one stereotyped mechanical process. Outcasts of civilization flung into the world of savagery, they had in the beginning none of the adaptability and none of the resources of the savage — knew nothing of the properties of unfamiliar plants, knew neither what to weave nor how to weave it, and often from sheer lack of understanding, starved and shivered in the midst of plenty. It was not till they had suffered long and intolerably that they learned to clothe themselves from such material as their new world afforded, to cure skins of animals and stitch them together into garments. In the first years of ruin only ratskins were plentiful; but, as time went on, rabbits, cats and wild dogs multiplied and, spreading through the countryside, were trapped and hunted for their flesh and the warmth of their skins. The dogs, as they bred, reverted to a mongrel and wolf-like type which, in summer, preyed largely on vermin; in winter, when scarcity of food made them bold, they prowled in packs, were a danger to the solitary and a legendary terror to children.

In the beginning the village was a straggle of rude huts, the tribesmen building how and where they would; later it took shape within its first wall and was roughly circular, enclosed by a fence of stake and thornbush. The raising of the fence was a sign and result of the beginning of primitive competition in armament; it was the knowledge that one village had fortified itself that set others to the driving in of stakes. One November evening Theodore, trudging in with his catch, saw a group round the headman’s fire; the centre of interest, a youth who had returned from poaching on other men’s land and brought back news of their doings. His trespassing had taken him within sight of the neighbouring village — which lately was a cluster of huts, like their own, and now was surrounded by a wall. A stockade, fully the height of a man, with only one gap for a gate…. The poacher’s news was discussed with uneasy interest. The fortified tribe, in point of numbers, was already stronger than its rival; if it added this new advantage to its numbers, what was there to prevent it from raiding and robbing as it would? Having raided and robbed, it could shelter behind its defences — beat off attack, make sorties and master the countryside! Its security meant the insecurity of others, the dependence of others on its goodwill and neighbourly honesty; the issue was as plain to the handful of tribesmen as to old-time nations competing in battleships, aeroplanes and guns, and the suspicions muttered round the headman’s fire were the raw material of arguments once familiar in the councils of emperors.

In the end, as the result of uneasy discussion, Theodore and another were dispatched to spy out the new menace, to get as near as they might to the wall, ascertain its strength and the method of its building; and with their return from a night expedition there was more consultation and a hurried planning of defences. Before winter was over the haphazard settlement was a compound, a walled town in embryo; within the narrow limits of a circle small enough for a handful of men to defend all huts were crowded, all provisions stored, all animals driven at sunset — so that, in case of night attack, no man could be cut off and the strength of the tribe be at hand to resist the assailants. With waste, healthy miles stretching out on either side, the village itself was an evil-smelling huddle of cabins; since a short stretch of wall was easier to defend than a long, men and beasts were crowded together in a foulness that made for security. In times of feud — and times of feud were seldom distant — stones were heaped beside the barrier, in readiness to serve as missiles, watch and ward was kept turn and turn by the able-bodied and — naturally, inevitably and almost unconsciously — there was evolved a system of military discipline, of penalty for mutiny and cowardice.

As in every social system from the beginning of time, the community was welded to a conscious whole not by the love its members bore to each other, but by hatred and fear of the outsider; it was the enemy, the urgent common need to be saved from him, that made of man a comrade and a citizen; the peril from outside was the natural antidote to everyday hatreds and the ceaseless bickerings of close neighbours. The instinctive politics of a squalid village were in miniature the policy of vanished nations, and untraditioned little headmen, like dead and gone kings, quelled internal feuds by diverting attention to the danger that threatened from abroad. The foundations of community life in the new world, like the foundations of community life in the old, were laid in the selfishness of fear; but for all its base origin the life of the community imposed upon its members the essential virtues of the soldier and citizen, a measure of discipline and sacrifice. From these, in time, would grow loyalty and pride in sacrifice; the enclosure of ramshackle huts and pens was breaking its savages to achievements undreamed of and virtues as yet beyond their ken; the blind, stubborn instincts that created Babylon — created London and Rome and destroyed them — were laying well and truly in a mudwalled compound the foundations of cities which should rise, flourish, perish in the stead of London and of Rome.

“The idea took fast root and grew in him — the idea of a world that, time and again, had returned to the helplessness of childhood.” — An early example of the science fiction trope sometimes called Precursors or Advanced Ancient Humans.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.