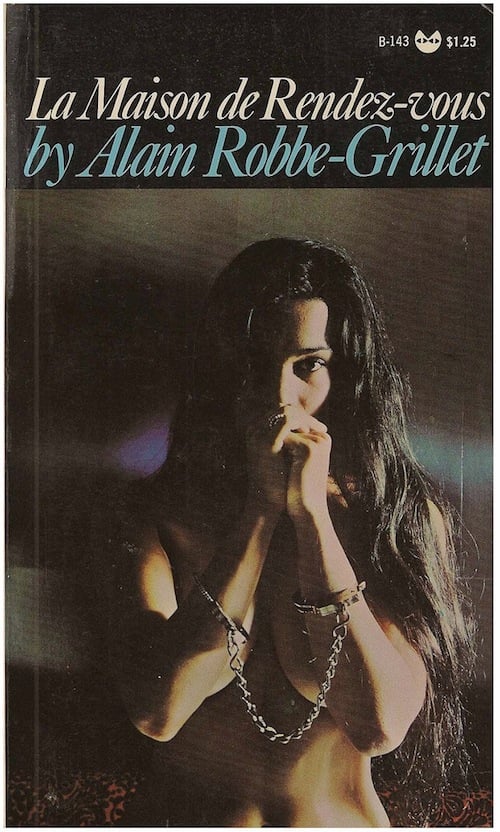

La Maison de Rendez-vous

By:

July 27, 2013

When La Maison de Rendez-vous appeared in 1966, Alain Robbe-Grillet hadn’t published a novel for 6 years. The nouveau roman iconoclast had been lured to the cinema, providing the screenplay for Alain Resnais’ L’Année dernière à Marienbad, and writing and directing his own feature, L’Immortelle. Both films were well received, and perhaps it was on a wave of self-confidence that he returned to fiction with such an audacious, unapologetic, doubling-down on his antagonism to “obsolete” realistic fiction. The double game of La Maison de Rendez-vous is made explicit in a pair of prefacing notes, presented with a straight face as if they didn’t completely contradict one another:

Author’s note: this novel cannot, in any way, be considered as a document about like in the British Territory of Hong Kong. Any resemblance to the latter in settings or situations is merely the effect of chance, objective or not.

Should any reader familiar with Oriental ports suppose that the places described below are not congruent with reality, the author, who has spent most of his life there, suggests that he return for another, closer look, things change fast in such climes.

The best of Robbe-Grillet’s early books, like Le Voyeur, or Jalousie, are notorious for dry, almost clinical description, and their narrative kick rises precisely from the tension between this hyper-controlled surface and the barely glimpsed obsessions that seethe beneath. But La Maison de Rendez-vous is deliriously, willfully lurid, an Orientalist fever dream of excess, where a handful of images — often hopelessly unsavory — are relentlessly tumbled and polished, shuffled into inconsistent scenarios of cause and effect, expanded, exploded and re-knit to answer the desires of a restless, obsessive narrator whose tastes are fixed upon the worst of colonial stereotypes of casual racism, sexism, drug use, and violence.

To term the book’s imagery — which apart from the twisting narrative form, offers its only subject — objectionable is an observation on a par with calling water wet. It’s certainly true that the book’s colonial fetishism functions as a critique: the unreality is always explicit, and the distance between the narrator’s warped desire and any “real” Hong Kong is clear, and clearly damning. But at the same time, well, Robbe-Grillet is having a blast — and it’s impossible to ignore how his later novels, like Projet pour une Révolution à New-York, go even farther in their deployment of sadistic, sexist imagery.

But La Maison de Rendez-vous isn’t there yet. The calculated delirium of Robbe-Grillet’s most cheerful assault remains a necessary challenge, to narrative sense as well as tender sensibilities.