Regression Toward the Zine (1)

By:

June 23, 2013

A 25-part series in which HiLobrow editor Joshua Glenn, who from 1990–93 published the zine Luvboat Earth and from 1992–2001 published the zine/journal Hermenaut, bids a fond farewell to his noteworthy collection of zines, which he recently donated to the University of Iowa Library’s zine and amateur press collection. CLICK HERE to view the online finding aid for this collection.

Science fiction began with utopian fiction — only to metastasize and evolve into a sprawling genre within which utopian fiction would come to represent only one of many sub-genres. And the zine as we know it began (in the late 1920s) with the science-fiction fanzine — only to metastasize and evolve into a sprawling genre within which the fanzine would come to represent only one of many sub-genres. According to the logico-chiasmatic rule of inverted parallelism, then, the zine is by its very birthright a utopian phenomenon. Q.E.D.

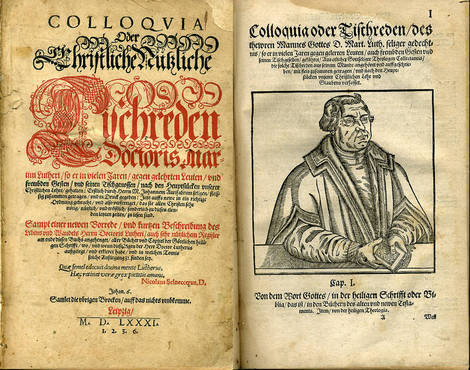

To continue the parallel investigation of science fiction and zines, for a moment longer: Some sf exegetes would like to locate science fiction’s origin in the Epic of Gilgamesh (eco-catastrophe); or King Revaita’s trip to and from heaven in the Mahabharatha (time travel); or the interplanetary trip in Lucian’s satirical True History (spaceflight); or the automaton mentioned in the Lie Zi (robots). In a similar fashion, some zine exegetes would encourage us to believe that the very first zinesters were controversialist pamphleteers from the Reformation (e.g., Martin Luther) through the Elizabethan age (e.g., Thomas Nashe) and the political and religious controversies of 17th-century England (e.g., Jonathan Swift), thence through the pre- and post-Revolutionary 18th century in America (e.g., Thomas Paine, Hamilton and Madison) and France (e.g., Voltaire, Rousseau, Burke), right through early 20th-century Fabian Society pamphleteering. Hmm…

It’s true: Zines are the descendants of pamphlets. Both are examples of DIY publishing. However, am I the only one who finds such genealogical exercises cringe-worthy? They can seem like a pathetic, feeble effort to get the public to take zines (or science fiction) seriously. Screw that! Zines should be taken seriously on their own merits.

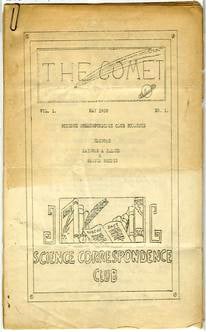

Fanzines first appeared in the late ’20s and early ’30s. They were not published by high-minded, articulate advocates of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. They were published by freaks and geeks. The publishers of the so-called Zine Revolution (1984–1993, in my eccentric periodization) might sometimes channel Thomas Paine or Rousseau, but mostly they were channeling the original freaky zinesters: sf fans.

In the late 1920s and early ’30s, science fiction fans rebelled against the hegemony of sf magazines — which shaped the dominant discourse of sf culture. Much as they enjoyed these magazines, hardcore science fiction fans desired something more. They wanted their own voices to be heard — not merely relegated to the Letters to the Editors page.

A note on nomenclature: By the 1940s, amateur fan publications were calling themselves fanzines and then simply zines. Whether to call this new phenomenon a zine or ’zine has been an open question from the beginning; those of us who prefer the former do so because the latter’s apostrophe seems a vestigial link back to magazines. Zines are not wannabe magazines; they were invented by those who were frustrated by the limitations of even their favorite magazines. Limitations which have to do with who gets to say what, and what sorts of topics and modes of expression are considered appropriate.

The birth of the zine was a populist revolution… though again, let’s not over-glamorize anything. There is much to mock — or simply to find tedious — in the world of fanzines and zines! However, there is also much to admire: passion, obsession, originality, unique visions.

Zine publishers are lonely freaks who, via zines, form communities of freaks. The zinester community’s form — loosely networked, dissensual — is not utopian in the sense of a perfectly regulated and harmonious social order. Instead, the form of the zinester community is what Western Marxist theorists describe as a “non-totalizing totality”: a whole that nevertheless does not force any of its parts to conform.

Rather than utopian, the zinester community is (to borrow a term from Fredric Jameson) an anti-anti-utopian one. Which is a beautiful thing.

NOTE: The next few installments of this series will look at proto-zines and early fanzines. Except as noted, the zines mentioned are not included in my own collection.

PS: The University of Iowa’s zine page has a very thoughtful and balanced take on the origin and definition of zines.