Theodore Savage (12)

By:

May 27, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the twelfth installment of our serialization of Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (also known as Lest Ye Die). New installments will appear each Monday for 25 weeks.

When war breaks out in Europe — war which aims successfully to displace entire populations — British civilization collapses utterly and overnight. The ironically named Theodore Savage, an educated and dissatisfied idler, must learn to survive by his wits in the new England, where 20th-century science, technology, and culture are regarded with superstitious awe and terror.

The book — by a writer best known today for her suffragist plays, treatises, and activism — was published in 1922. In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish it in a gorgeous paperback edition, with an Introduction by Gary Panter.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

From that day forward they lived isolated, without sight or sound of men. Chance had led them to a loneliness which was safety, coupled with a bare possibility of supporting life — by rooting in fields left derelict, by fishing and the snaring of birds; but for all their isolation it was long before they ceased to peer for men on the horizon, to take careful precautions against the coming of their own kind. With the memory of savagery and violence behind them, they looked round sharply at an unaccustomed sound, kept preferably to woods and shadow and moved furtively in open country; and Theodore’s ultimate choice of a dwelling-place was dictated chiefly by fear of discovery and desire to remain unseen. What he sought was not only a shelter, a roof-tree, but a hiding-place which other men might pass without notice; hence he settled at last in a fold of the hills — in a copse of tall wood, some four or five miles from their first halt, where oaks and larches, bursting into bud, denied the ruin that had come upon last year’s world…. Theodore, setting foot in the wood for the first time — seeking refuge, a hiding-place to cower in — was suddenly in presence of the green life unchanging, that blessed and uplifted by its very indifference to the downfall and agony of man. The wind-flowers, thrusting through brown leaves, were as last year’s windflowers — a delicate endurance that persisted…. He had entered a world that had not altered since the days when he lived as a man.

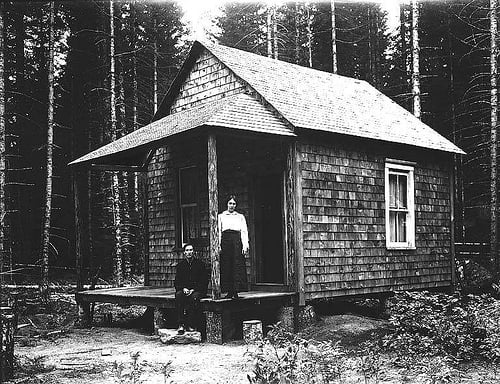

He explored his little wood with precaution, creeping through it from end to end; and, finding no more recent sign of human occupation than a stack of sawn logs, their bark grey with mould, he decided on the site of his camp and refuge — a clearing near the stream that babbled down the valley, but well hidden by its thick belt of trees. The girl had followed him — she dreaded being left alone of all things — and assented with her customary listlessness when he explained to her that the bird-life and the stream would mean a food-supply and that the logs, ready cut, could be built into shelters from the weather; she was a town-dweller, mentally as well as by habit of body, whom the spring of the woods had no power to rouse from her apathy.

There were empty cottages for the taking lower down the valley and it was the fear of the marauder alone that sent them to camp in the wilderness, that kept them lurking in their fold of the hills, not daring to seek for greater comfort. Within a day or two after they had discovered it, they were hidden away in the solitary copse, their camp, to begin with, no more than a couple of small lean-to’s — logs propped against the face of a projecting rock and their interstices stuffed with green moss. In the first few weeks of their lonely life they were often near starvation; but with the passing of time food was more abundant, not only because Theodore grew more skilled in his fishing and snaring — learned the haunts of birds and the likely pools for fish — but because, as spring ripened, they inherited in the waste land around them a legacy of past cultivation, fruits of the earth that had sown themselves and were growing untended amidst weeds.

With time, with experiment and returning strength, Theodore made their refuge more habitable; tools, left lying in other men’s houses, fields and gardens, were to be had for the searching, and, when he had brought home a spade discovered in a weed-patch and an axe found rusting on a cottage floor, he built a clay oven that their fire might not quench in the rain and hewed wood for the bettering of their shelters. Ada — when he told her where to look for it — gathered moss and heather for their bed-places and spread it to dry in the sun; and from one of his more distant expeditions he returned with pots which served for cooking and the carrying of water from the stream…. Spring lengthened into summer and no man came near them; they lived only to themselves in a primitive existence which concerned itself solely with food and bodily security.

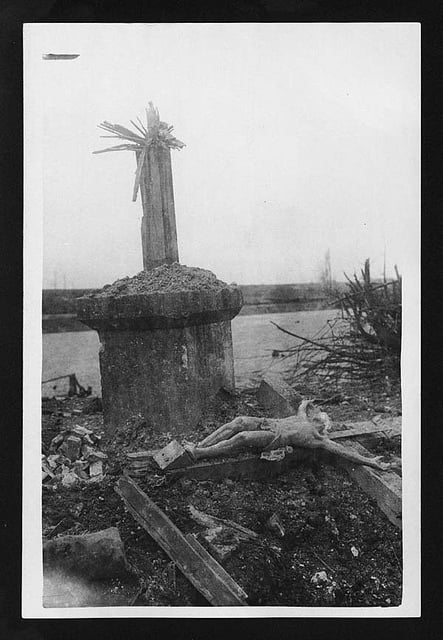

As the days grew longer and the means of subsistence were easier to come by, Theodore would go further afield — still moving cautiously over open country, but no longer expectant of onslaught. In the immediate neighbourhood of his daily haunts and hunting-grounds was no sign of human life and work save a green cart-track that ended on the outskirts of his copse; but lower down the valley were ploughed fields lapsing into weed-beds, here and there an orchard or a garden-patch and hedges that straggled as they would. Lower down again was another wide belt of burned land which, so far, he had not entered — trees on either side the stream, stood gaunt and withered to the farthest limit of his sight. The district, even when alive and flourishing, had seemingly been sparsely populated; its lonely dwellings were few and far apart — a farmhouse here, a clump of small cottages there, all bearing traces of the customary invasion by the hungry. Sheep-farming had been one of the local industries, and hillsides and fields were dotted with the skeletons of sheep — left lying where vagabond hunger had slaughtered them and ripped the flesh from their bones.

As the year rolled over him, Theodore came to know the earth as primitive man and the savage know it — as the source of life, the store-house of uncertain food, the teacher of cunning and an infinite and dogged patience. When the weather made wandering or fishing impossible he would sit under shelter, with his hands on his knees, passive, unimpatient, hardly moving through long hours, while he waited for the rain to cease. It was months before there stirred in him a desire for more than safety and his daily bread, before he thought of the humanity he had fled from except with fear and a shrinking curiosity as to what might be happening in the world beyond his silent hills. In his body, exhausted by starvation, was a mind exhausted and benumbed; to which only very gradually — as the quiet and healing of Nature worked on him — the power of speculation and outside interest returned. In the beginnings of his solitary life he still spoke little and thought little save of what was personal and physical; cut off mentally from the future as well as from the past, he was content to be relieved of the pressure of hunger and hidden from the enemy, man.

Of the woman whom chance and her own helplessness had thrown upon his hands he knew, in those first months, curiously little. She remained to him what she had been from the moment she clutched at his arm and fled with him — an encumbrance for which he was responsible — and as the numbness passed from his brain and he began once more to live mentally, she entered less and less into his thoughts. She was Ada Cartwright — as pronounced by its owner he took the name at first for Ida — ex-factory hand and dweller in the north-east of London; once vulgarly harmless in the company of like-minded gigglers, now stupefied by months of fear and hunger, bewildered and incapable in a life uncivilized that demanded of all things resource. As she ate more plentifully and lost her starved hollows, she was not without comeliness of the vacant, bouncing type; a comeliness hidden from Theodore by her tousled hair, her tattered garments and the heavy wretchedness that sulked in her eyes and turned down the corners of her mouth. She was helpless in her new surroundings, with the dazed helplessness of those who have never lived alone or bereft of the minor appliances of civilization; to Theodore, at times, she seemed half-witted, and he treated her perforce as a backward child, to be supervised constantly lest it fail in the simplest of tasks.

It was his well-meant efforts to renew her scanty and disreputable wardrobe that first revealed to him something of the mind that worked behind her outward sullen apathy. In the beginning of disaster clothing had been less of a difficulty than the other necessities of life; long after food was a treasure beyond price it could often be had for the taking and, when other means of obtaining it failed, those who needed a garment would strip it from the dead, who had no more need of it. In their hidden solitude it was another matter, and they were soon hard put to it to replace the rags that hung about them; thus Theodore accounted himself greatly fortunate when, ransacking the rooms of an empty cottage, he came on a cupboard with three or four blankets which he proceeded to convert into clothing by the simple process of cutting a hole in the middle. He returned to the camp elated by his acquisition; but when he presented Ada with her improvised cloak, the girl astonished him by turning her head and bursting into noisy tears.

“What’s the matter?” he asked her, bewildered. “Don’t you like it?”

She made no answer but noisier tears, and when he insisted that it would keep her nice and warm her sobs rose to positive howls; he stared at her uncertainly as she sat and rocked, then knelt down beside her and began to pat and soothe, as he might have tried to soothe a child. In the end the howls diminished in volume and he obtained an explanation of the outburst — an explanation given jerkily, through sniffs, and accompanied by much rubbing of eyes.

No, it wasn’t that she didn’t want it — she did want it — but it reminded her… It was so ’ard never to ’ave anything nice to wear. Wasn’t she ever going to ’ave anything nice to wear again — not ever, as long as she lived?… She supposed she’d always got to be like this! No ‘airpins — and straw tied round her feet instead of shoes!… Made you look as if you’d got feet like elephants — and she’d always been reckoned to ’ave a small foot…. Made you wish you was dead and buried!…

He tried two differing lines of consolation, neither particularly successful; suggesting, in the first place, that there was no one but himself to see what she looked like, and, in the second, that a blanket could be made quite becoming as a garment.

“That’s a lie,” Ada told him sulkily. “You know it ain’t becoming — ’ow could it be? A blanket with an ’ole for the ’ead!… Might just as well ’ave no figure. Might just as well be a sack of pertaters…. I wonder what anyone would ’ave said at ’ome if I’d told ’em I should ever be dressed in a blanket with an ’ole for the ’ead!… And I always ’ad taiste in my clothes — everyone said I ’ad taiste.”

And — stirred to the soul by the memory of departed chiffon, by the hideous contrast between present squalor and former Sunday best — her howls once more increased in volume and she blubbered with her head on her knee.

Theodore gave up the attempt at consolation as useless, leaving her to weep herself out over vanished finery while he busied himself with the cooking of their evening meal; and in due time she came to the end of her stock of emotion, ceased to snuffle, ate her supper and took possession of the blanket with the ’ole for the ’ead — which she wore without further complaint. The incident was over and closed; but it was not without its significance in their common life. To Theodore the tragicomic outburst was a reminder that his dependent, for all her childish helplessness, was a woman, not only a creature to be fed; while the stirrings of Ada’s personal vanity were a sign and token that she, also, was emerging from the cowed stupor of body and mind produced by long terror and starvation, that her thoughts, like her companion’s, were turning again to the human surroundings they had fled from…. Man had ceased to be only an enemy, and the first sheer relief at security attained was mingling, in both of them, with the desire to know what had come to a world that still gave no sign of its existence. Order, the beginnings of a social system (so Theodore insisted to himself) must by now have risen from the dust; but meanwhile — because order restored gave no sign and the memory of humanity debased was still vivid — he showed himself with caution against the skyline and went stealthily when he broke new ground. There were days when he lay on a hill-top and scanned the clear horizon, for an hour at a time, in the hope that a man would come in sight; just as there were nights, many, when he lived his past agonies over again and started from his sleep, alert and trembling, lest the footstep he had dreamed might be real. Meanwhile he made no move towards the world he had fled from — waiting till it gave him a sign.

If he had been alone in his wilderness, unburdened by the responsibility of Ada and her livelihood, it is probable that, before the days shortened, he would have embarked upon a journey of cautious exploration; but there was hazard in taking her, hazard in leaving her, and their safety was still too new and precious to be lightly risked for the sake of a curious adventure — which might lead, with ill-luck, to discovery of their secret place and the enforced sharing of their hidden treasure of food. Further, as summer drew on towards autumn, though his haunting fear of mankind grew less, his work in his own small corner of the earth was incessant and, in preparation for the coming of winter, he put thought of distant expedition behind him and busied himself in making their huts more weatherproof, as well as roomier, in the storing of firewood under shelter from the damp, and in the gathering together of a stock of food that would not rot. He made frequent journeys — sometimes alone, sometimes with Ada trudging behind him — to a derelict orchard in the lower valley which supplied them plentifully with apples; he had provided himself with a wet-weather occupation in the twisting of osiers into clumsy baskets — which were rilled in the orchard and carried to their camping-place where they spread out the apples on dried moss…. With summer and autumn they fared well enough on the harvest of other men’s planting; and if Theodore’s crude and ignorant experiments in the storage of fruit and vegetables were failures more often than not, there remained sufficient of the bounty of harvest to help them through the scarcity of winter.

It was with the breaking of the next spring that there came a change into the life that he lived with Ada.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.