Theodore Savage (8)

By:

April 29, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the eighth installment of our serialization of Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (also known as Lest Ye Die). New installments will appear each Monday for 25 weeks.

When war breaks out in Europe — war which aims successfully to displace entire populations — British civilization collapses utterly and overnight. The ironically named Theodore Savage, an educated and dissatisfied idler, must learn to survive by his wits in the new England, where 20th-century science, technology, and culture are regarded with superstitious awe and terror.

The book — by a writer best known today for her suffragist plays, treatises, and activism — was published in 1922. In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish it in a gorgeous paperback edition, with an Introduction by Gary Panter.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

Someone else asked him about the rumour ever-current of negotiation — whether there was truth in it, whether he had heard anything?

“Much what you’ve heard,” he said, and shrugged his shoulders. “There’s talk — there always is — plenty of it; but I don’t suppose I know any more than you do…. It stands to reason that someone must be trying to put an end to it — but who’s trying to patch it up with who? … And what is there left to patch? Lord knows! They say the real trouble is that when governments have gone there’s no one to negotiate with. No responsible authority — sometimes no authority at all. Nothing to get hold of. You can’t make terms with rabble; you can’t even find out what it wants — and it’s rabble now, here, there, and everywhere. When there’s nothing else left, how do you get hold of it, treat with it? Who makes terms, who signs, who orders? … Meanwhile, we go on till we’re told to stop — those of us that are left…. And I suppose they’re doing much the same — keeping on because they don’t know how to stop.”

Theodore asked what he meant when he spoke of “no government.” ‘You can’t mean it literally? You can’t mean….?”

“Why not?” said the pilot. “Is there any here?”— and jerked his head, this time towards the road. Its long white ribbon was spotted with groups and single figures of vagrants — scarecrow vagrants — crawling onward they knew not whither.

“See that,” he said, “see that — does anyone govern it? Make rules for it, defend it, keep it alive? … And that’s everywhere.”

Someone whispered back “Everywhere” under his breath; the rest stared in silence at the spotted white ribbon of road.

“You can’t mean…?” said Theodore again.

The airman shrugged his shoulders and laughed roughly.

“I believe,” he said, “there are still some wretched people who call themselves a government, try to be a government — at least, there were the other day…. Sometimes I wonder how they try, what they say to each other — poor devils! How they look when the heads of what used to be departments bring them in the day’s report? Can’t you imagine their silly, ghastly faces? … Even if they’re still in existence, what in God’s name can they do — except let us go on killing each other in the hope that something may turn up. If they give orders, sign papers, make laws, does anyone listen, pay any attention? Does it make any difference to that?” Again he jerked his head towards the road, and in the word as in the gesture was loathing, fear and contempt. “And in other parts of what used to be the civilized world — where this sort of hell has been going on longer — what do you suppose is happening?”

No one answered; he laughed again roughly, as if he were contemptuous of their hopes, and a man beside Theodore — a corporal — swung round on him, white-faced and snarling.

“Damn you! … I’ve got a girl … I’ve got a girl! … ”

He choked, moved away and stood rigid, staring at the road.

Theodore heard himself asking, “If there isn’t any government — what is there?”

“What’s left of the army,” said the other, “that’s all that hangs together. Bits of it, here and there — getting smaller, losing touch with the other bits; hanging on to its rations — what’s left of ’em…. And we hold together just as long as we can fight back the rabble; not an hour, not a minute longer! When we’ve gnawed our way through the last of our rations — what then? … You may do what you like, but I’m keeping a shot for myself. Whether we’re through with it or whether we’re not. Just stopping fighting won’t clear up this mess…. And I’ll die — what I am. Not rabble!”

Whether after days or whether after weeks, there came a time when they ceased to have dealings with the world beyond their wire defences; when the store-sheds in the camp were all but emptied of their hoard of food-stuffs and such military authority as might still exist took no further interest in the doings of a useless garrison. Orders and communications, once frequent, grew fewer, and finally, as military authority crumbled, they were left to isolation, to their own defence and devices. Since no man any longer had need of them, they were cut off from intercourse with those other remnants of the life disciplined whence lorries had once arrived in search of rations; separated from such other bands of their fellows as still held together, they were no longer part of an army, were nothing but a band of armed men. Though their own daily rations were cut down to the barest necessities of life, there was little grumbling, since even the dullest knew the reason; as the airman had told them, they were living on their own fat, for so long as their own fat lasted. For all their isolation, their fears and daily perils kept them disciplined; they held together, obeyed orders and kept watch, not because they still felt themselves part of a nation or a military force, but because there remained in their common keeping the means to support bare life. It was not loyalty or patriotism, but the sense of their common danger, their common need of defence against the famished world outside their camp, that kept them comrades, obedient to a measure of discipline, and made them still a community.

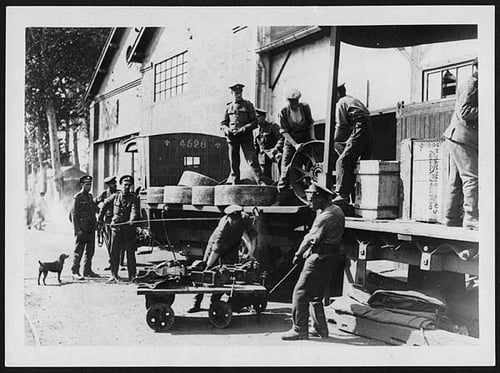

There had been altercation of the fiercest before they were left to themselves — when lorries drove up for food which was refused them, on the ground that the camp had not sufficient for its own needs. Disputes at the refusal were furious and violent; men, driven out forcibly, went off shouting threats that they would come back and take what was denied them — would bring their machine-guns and take it. Those who yet had the wherewithal to keep life in their bodies knew the necessity that prompted the threat and lived thenceforth in a state of siege against men who had once been their comrades. With the giving out of military supplies and the consequent breaking of the bonds of discipline, bands of soldiers, scouring the countryside, were an added terror to their fellow-vagrants and, so long as their ammunition lasted, fared better than starvation unarmed… If central authority existed it gave no sign; while military force that had once been united — an army — dissolved into its primitive elements: tribes of armed men, held together by their fear of a common enemy. In the wreck of civilization, of its systems, institutions and polity, there endured longest that form of order which had first evolved from the chaos of barbarism — the disciplined strength of the soldier…. A people retracing its progress from chaos retraced it step by step.

The end of civilization came to Theodore Savage and his fellows as it had come to uncounted thousands.

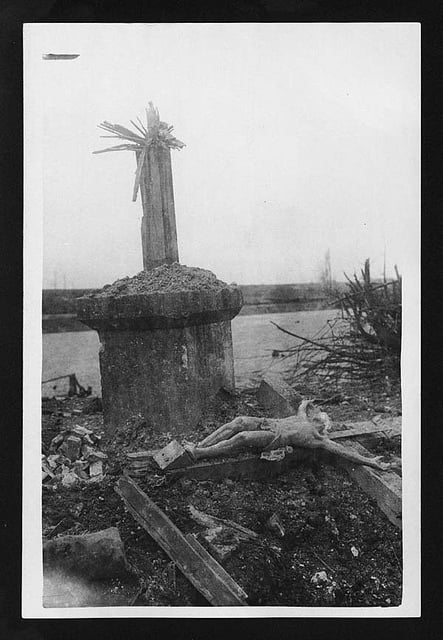

There had been a still warm day with a haze on it — he judged it early autumn or perhaps late summer; for the rest, like any other day in the camp routine — of watchfulness, of scanning the sky and the distance, of the passing of vagabond starvation, of an evil smell drifting with the lazy air from the dead who lay unburied where they fell. Before night-fall the haze was lifted by a cold little wind from the east; and soon after darkness a moon at the full cast white, merciless light and black shadow.

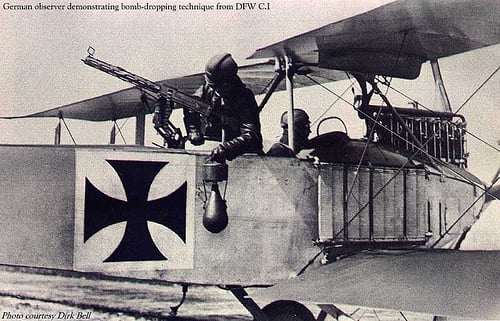

Theodore was asleep when the alarm was given — by a shout at the door of his hut. One of ten or a dozen, aroused like himself, he grabbed at his rifle as he stumbled to his feet; believing in the first hurried moment of waking that he was called to drive back yet another night onslaught of the starving enemy without. He ran out of the hut into a strong, pallid glare that wavered…. A stretch of gorse and bramble-patch two hundred yards away was alight, burning lividly, and further off the same bluish flame was running like a wave across a field. Enemy aeroplanes were dropping their fire-bombs — here and there, flash on flash, of pale, inextinguishable flame. It was scarcely five minutes from the time he had been roused before the camp and its garrison had ceased to exist as a community, and Theodore Savage and his living comrades were vagabonds on the face of the earth. The gorse and bramble-patch lay to the eastward and the wind was blowing from the east; the flames rushed triumphantly at a black clump of fir-trees — great torches that lit up the neighbourhood. The guiding hand in the terror overhead had a mark laid ready for his aim; the camp, with its camouflaged huts and sheds, seen plainly as in broadest daylight. His next bomb burst in the middle of the camp blowing half-a-score of soldiers into bloody fragments and firing the nearest wooden building. While it burned, the terror overhead struck again and again — then stooped to its helpless quarry and turned a machine-gun on men in trenches and men running hither and thither in search of a darkness that might cover them…. That, for Theodore Savage, was the ending of civilization.

With the crash of the first explosion he cowered instinctively and pressed himself against the wall of the nearest shed; the flames, rushing upward, showed him others cowering like himself, all striving to obliterate themselves, to shrink, to deny their humanity. Even in his extremity of bodily fear he was conscious of merciless humiliation; the machine-gun crackled at scurrying little creatures that once were men and that now were but impotent flesh at the mercy of mechanical perfection…. Mechanical perfection, the work of men’s hands, soared over its creators, spat down at their helplessness and defaced them; they cringed in corners till it found them out and ran from it screaming, without power to strike back at the invisible beast that pursued them. Without power even to surrender and yield to its mercy; they could only hate impotently — and run….

As they ran they broke instinctively — avoiding each other, since a group made a mark for a gunner. Theodore, when he dared cower no longer, rushed with a dozen through the gate of the camp but, once outside it, they scattered right and left and there was no one near him when his flight ended with a stumble. He stayed where he had fallen, a good mile from the camp, in the blessed shadow of a hedgerow; he crept close to it and lay in the blackness of the shadow, breathing great sobs and trembling — crouching in dank grass and peering through the leafage at the distant furnace he had fled from. The crackling of machine-guns had ceased, but here and there, for miles around were stretches of flame running rapidly before a dry wind. Half a mile away an orchard was blazing with hayricks; and he drew a long sigh of relief when another flare leaped up — further off. That was miles away, that last one; they were going, thank God they were going! … He waited to make sure — half-an-hour or more — then stumbled back in search of his companions; through fields on to the road that led past what once had been the camp.

On his way he met others, dark figures creeping back like himself; by degrees a score or so gathered in the roadway and stood in little groups, some muttering, some silent, as they watched the flames burn themselves out. There were bodies lying in the road and beside it — men shot from above as they ran; and the living turned them over to look at their distorted faces…. No one was in authority; their commanding officer had been killed outright by the bursting of the first bomb, one of the subalterns lay huddled in the roadway, just breathing. So much they knew…. In the beginning there was relief that they had come through alive; but, with the passing of the first instinct of relief, came understanding of the meaning of being alive…. The breath in their bodies, the knowledge that they still walked the earth: and for the rest, vagrancy and beast-right — the right of the strongest to live!

They took counsel together as the night crept over them and — because there was nothing else to do — planned to search the charred ruin as the fire died out, in the hope of salvage from the camp. They counted such few, odd possessions as remained to them: cartridge belts, rifles thrown away in flight and then picked up in the road, the contents of their pockets — no more…. In the end, for the most part, they slept the dead sleep of exhaustion till morning — to wake with cold rain on their faces.

The rain, for all its wretchedness to men without shelter, was so far their friend that it beat down the flames on the smouldering timbers which were all that remained of their fortress and rock of defence. They burrowed feverishly among the black wreckage of their store-sheds, blistering and burning their fingers by too eager handling of logs that still flickered, unearthing, now and then, some scrap of charred meat but, for the most part, nothing but lumps of molten metal that had once been the tins containing food. In their pressing anxiety to avert the peril of hunger they were heedless of a peril yet greater; their search had attracted the attention of others — scarecrow vagrants, the rabble of the roads, who saw them from a distance and came hurrying in the hope of treasure-trove. The first single spies retreated at the order of superior and disciplined numbers; but with time their own numbers were swollen by those who halted at the rumour of food, and there hovered round the searchers a shifting, snarling, envious crowd that drew gradually nearer till faced with the threat of pointed rifles. Even that only stayed it for a little — and, spurred on by hunger, imagining riches where none existed, it rushed suddenly forward in a mob that might not be held.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.