Goslings (18)

By:

April 5, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the eighteenth installment of our serialization of J.D. Beresford’s Goslings (also known as A World of Women). New installments will appear each Friday for 23 weeks.

When a plague kills off most of England’s male population, the proper bourgeois Mr. Gosling abandons his family for a life of lechery. His daughters — who have never been permitted to learn self-reliance — in turn escape London for the countryside, where they find meaningful roles in a female-dominated agricultural commune. That is, until the Goslings’ idyll is threatened by their elders’ prejudices about free love!

J.D. Beresford’s friend the poet and novelist Walter de la Mare consulted on Goslings, which was first published in 1913. In May 2013, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of the book. “A fantastic commentary upon life,” wrote W.L. George in The Bookman (1914). “Mr. Beresford possesses the rare gift of divination,” wrote The Living Age (1916). “It is piece of the most vivid imaginative realism, as well as a challenge to our vaunted civilization.” “At once a postapocalyptic adventure, a comedy of manners, and a tract on sexual and social equality, Goslings is by turns funny, horrifying, and politically stirring,” says Benjamin Kunkel in a blurb for HiLoBooks. “Most remarkable of all may be that it has not yet been recognized as a classic.”

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23

5

After a marked preliminary hesitation the committee appointed Jasper Thrale chief mechanic of Marlow. The hesitation was understandable. Their only experience of the ways of men in this altered civilization had been drawn from observations of Mr Evans at Wycombe. His manner of life appeared representative of what they might expect. Nevertheless they did not openly condemn him, although he proved an immediate source of trouble, even to these organizers in Marlow. The youth of the place was apt to wander over the hill in the evenings; “just for fun,” they said. They went in twos and threes, and occasionally one of them stayed behind. These evening walks interfered with work. “Later on I shouldn’t mind so much,” Lady Durham had said, commenting on the loss of a young and active worker, “but there is so much to do just now.” Her comment showed that even then the situation was being accepted, and that many women were prepared to adapt their old opinions to new conditions. It also showed why the committee hesitated to accept Thrale’s services.

Thrale understood their difficulty, and went straight to the point.

“You are afraid that the young women will be wasting time, running after me,” he said. “Set your minds at rest. That won’t last. And if you give me pupils for my machinery I should prefer women over forty in any case. I believe I shall find them more capable.”

He was right in one way. When the excitement of his coming had subsided, he was not the cause of much wasted time. He adopted a manner with the younger women which did not encourage advances. He was, in fact, quite brutally frank. When the young women devised all kinds of impossible excuses to linger in his vicinity he sent them away with hot indignant faces. Among those who sought their sterile amusements in Wycombe it became the fashion openly to express hatred and contempt for “that engine fellow.” It was agreed that he “wasn’t a proper man.” Another section, however, talked scandal, and hinted that assistant-engineer Eileen was the cause of Thrale’s pretended misogyny.

The committee found their work more complicated in some respects after Thrale’s coming.

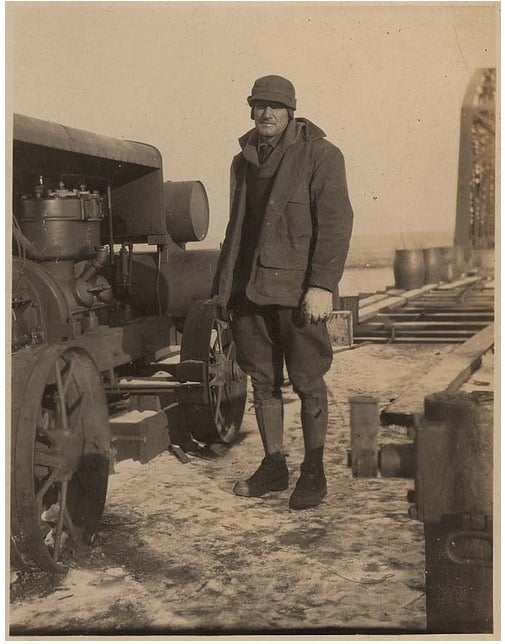

Thrale, himself, was supremely indifferent to any scandal or expression of hatred. He had his hands full, his hours of work were only limited by daylight, and six hours sleep was all he asked for or desired. After a very brief introduction to the intricacies of reaper and rake at the hands of Miss Oliver — her father had never been able to afford a binder, but the days of corn-harvest were still far ahead — he set himself to learn the mysteries of all the agricultural machinery in the neighbourhood; traction engines, steam ploughs and thrashing machines, and to pass on the knowledge he gained to his pupils. He found them stupid at first, but they were patient and willing for the most part.

Then, handicapped by the lack of coal, he rode over to Bourne End and discovered two locomotives. One of them was standing on the line a mile out of the station with a full complement of coaches attached, the other was an unencumbered goods engine in a siding. He chose the latter for his first experiment, and succeeded in driving it back to Marlow. It groaned and screamed in a way that indicated serious organic trouble, but after he had overhauled it, it proved capable of taking him to Maidenhead, where he found a sound engine in a shed.

After that he devoted three days to getting a clear line to Paddington, a tedious process which involved endless descents from the cab, and mountings into signal boxes, experiments with levers and the occasional necessity for pushing whole trains out of his path into some siding. But at last he returned with magnificent loot of coal from the almost untouched London yards beyond Ealing.

London was still the storehouse of certain valuable commodities.

His passage through the surrounding country was hailed with cries of amazement and jubilant acclamation. The first railway surely excited less astonishment than did Thrale on his solitary engine. Doubtless the unfortunate women who saw him pass believed that the gods of machinery had returned once more to bring relief from all the burden of misery and unfamiliar work.

And once the points were set and the way open to London by rail he could go and return with tools and many other necessaries that had offered no temptation to the starving multitude who had fled from the town.

Marlow was greatly blessed among the communities in those days.

The harvest was early that year, and Miss Oliver decided to cut certain fields of barley at the end of July.

Thrale’s energies were then diverted to the superintendence of the reapers and binders, and he rode from field to field, overlooking the work of his pupils or spending furious hours in struggle with some refractory mechanism.

One Saturday, an hour or two after midday, he was returning from some such struggle, when he saw a strange procession coming down that long hill from Handy Cross, which some pious women regarded as the road to hell.

Casual immigration had almost ceased by that time, but the sight indicated the necessity for immediate action. The immigration laws of Marlow, though not coded as yet, were strict; and only bona fide workers were admitted, and even those were critically examined.

Thrale shouted to attract attention and the procession stopped.

When he came through the gate on to the road, he was accosted by name.

“Oh, Mr Thrale, fancy finding you,” said the young woman at the pole of the truck.

The meeting of Livingstone and Stanley was far less amazing.

An old woman perched on the truck and partly sheltered by the remains of an umbrella, regarded his appearance with some show of displeasure.

“By rights ’e should ’ave written to me in the first place,” she muttered.

“Mother’s got a touch of the sun,” explained Blanche hurriedly.

Thrale had not yet spoken. He was considering the problem of whether he owed any duty to these wanderers, which could override his duty to Marlow.

“Where have you come from?” he asked.

Blanche and Millie explained volubly, by turns and together.

“You see, we don’t let anyone stay here,” said Thrale.

Blanche’s eyebrows went up and she waved her too exuberant sister aside. “We’re willing to work,” she said.

“And your mother?” queried Thrale. “And this other woman?”

“Ach! I work too,” put in Mrs Isaacson. “I have learnt all that is necessary for the farm. I milk and feed chickens and everything.”

“You’ll have to come before the committee,” said Thrale.

“Anywhere out of the sun,” replied Blanche, “and somewhere where we can put mother. She’s very bad, I’m afraid.”

“You can stay to-night, anyway,” returned Thrale.

Millie made a face at him behind his back, and whispered to Mrs Isaacson, who pursed her mouth.

“Well, you do seem more civilized here,” remarked Blanche as the procession restarted towards Marlow. Thrale, with something of the air of a policeman, was walking by the side of the pole.

“You’ve come at a good time,” was his only comment.

Millie had another shock before they reached the town. She saw what she thought was a second man, on horseback this time, coming towards them. Marlow, she thought, was evidently a place to live in. But the figure was only that of Miss Oliver in corduroy trousers, riding astride.

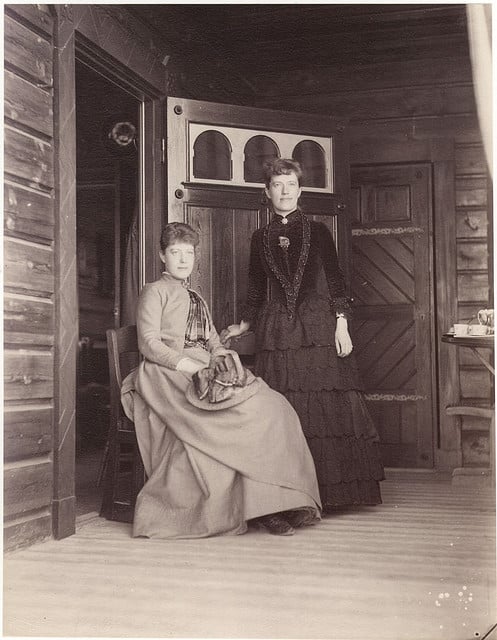

Fate had dropped the Goslings into Buckinghamshire to fulfil their destiny. They had been led to Marlow by a casual direction, here and there, after the first propulsion of Blanche’s instinct had sent them into the country beyond Harrow. And fate, doubtless with some incomprehensible purpose of its own in view, had quietly decided that in Marlow they were to stay. They had been dropped at a season when, for the first time in the long three months’ history of the community, there was a shortage of labour; and Blanche and Millie, browned by exposure and generally improved by their first six days of healthy life, were quite acceptable additions to the population at that moment. As for Mrs Isaacson, a lady of sufficient initiative and force of character to require no kindly interposition of Providence on her behalf, she arranged her own future as an expert of farm management, and incidentally as the Goslings’ housemate. Mrs Isaacson was a burr that would stick anywhere for a time. She displayed an unexpected and highly specialized knowledge of the management of farms, when confronted with the expert Miss Oliver who was far too embarrassed to press her questions home. The casual remarks of Aunt May and her helpers had been retained in Mrs Isaacson’s brilliant memory and she displayed her knowledge to the best possible advantage, filling the gaps with irrelevant volubility, gesture and histrionic struggles with the English language, which proved suddenly inadequate to the expression of these recondities that the German would have so aptly expressed. It was inferred that in her native Bavaria, Mrs Isaacson had farmed in the grand style.

Only Mrs Gosling, useless and ineligible, remained for consideration, and she for once took a firm line of her own, and defied the committee, Marlow generally, and the negligible remainder of the cosmos, to alter her determination.

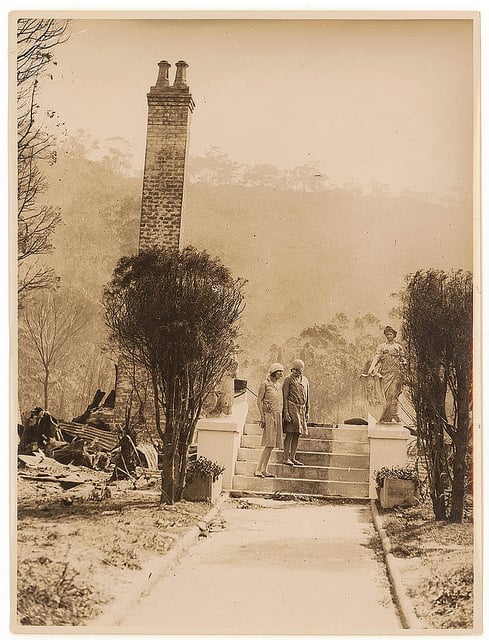

The home at which they had finally arrived did not suit her. The tiny cottage of three rooms in the little street that runs down to the town landing stage had no lace curtains in the front window, no suites of furniture, no hall to save the discreet caller from stepping through the front door straight into the single living-room, no accumulation of dustable ornaments, not even a strip of carpet or linoleum to cover the nakedness of a bricked floor. It was not civilized; it was not decent according to the refined standards of Wisteria Grove; it was an impossible place for any respectable woman to live in, and Mrs Gosling, with unexpected force of character, chose the obvious alternative. She did not, however, make any announcement of her determination; she was wrapped in a speculative depression that found no relief in words. She had been so ordered, hoisted, dragged and bumped through the detested country during the past six days that all show of authority had been taken from her. It may be that deep in her own mind she cherished a sullen and enduring resentment against her daughters, and had vowed to take the last and unanswerable revenge of which humanity is capable. But outwardly she preserved that air of incomprehension which had marked her during the last stages of their journey, and committed herself to no statement of the enormous plan which must have been forming in her mind.

When they took her into the small, brick-paved room and deposited her temporarily on a wooden-seated chair, while they unpacked what remained to them in the accursed trolly, Mrs Gosling took one brief but comprehensive survey of her naked surroundings.

“She’s a bit touched, isn’t she?” whispered Millie to her sister. “Do you think she understands where we are or what we’re doing?”

Blanche shook her head. “I expect she’ll be all right in a day or two,” she ventured, “It’s the sun.”

The two girls, stirred to a new outlook on life by the extraordinary experiences of the past months, were on the threshold of diverse adventures. After the toil and anxiety of their tramp through inhospitable country, and the hazard of the open air, this reception into a community and settlement into a permanent shelter afforded a relief which was too unexpected to be qualified as yet by criticism, or any comparison with past glories. They were young and plastic, and to each of them the future seemed to hold some promise; to them the silence and immobility of their mother could only be evidence of impaired faculties.

“We must get her to bed,” said Blanche.

Even when Mrs Gosling asked with perfect relevance, “Are we going to stop ’ere, Blanche?” they humoured her with evasive replies. “Well, for a day or two, perhaps,” and “Look here, don’t you worry about that. We’re going to put you to bed.”

Her head dropped again and she fell back into her moody silence. Doubtless she meditated on the many wrongs her daughters had done her, and wondered why she should have been brought out to die in this wilderness?

During the nine days that elapsed before her plan matured, she made no further comment on her surroundings. She lay in the upstairs room, sleeping little, with no desire ever again to face the terror of a world which demanded a new mode of thought. Unconsciously she had adopted Blanche’s phrase, “Everything’s different,” but to her the message was one of doom, she could not live in a different world.

And Blanche on her side was puzzled at her mother’s apathy and said, “I can’t understand it.” Yet both the changed conditions and Mrs Gosling’s unchangeable habit were fundamental things.

MODES OF EXPRESSION

1

In Marlow that year harvesting and thrashing were carried on simultaneously. August was very dry, and the greater part of the corn was never stacked at all. Thrale took his engines into the fields, and the shocks were loaded on to carts and fed directly into the thrasher. This method entailed some disadvantages, chief among them the retarding of the actual harvest-work, but on the whole it probably economized labour. The scheme would doubtless have been impracticable in the days of small private ownership, but it worked well in this instance, favoured as it was by the drought.

The saving of labour during those six weeks of furious toil was a matter of the first importance. The work, indeed, was too heavy for many of the women who were unable to stand the physical strain of hoisting sheaves from the waggons into the thrasher; and the sacks of grain proved so unmanageable that Thrale had to devise a makeshift hoist for loading them into the carts. In Marlow, at least, machinery was still triumphant, and the committee sighed their relief in the sentence: “I don’t know what we should have done without Jasper Thrale.” Nevertheless it is quite certain that they would have done without him if it had not been for that fortuitous meeting in Maidenhead.

For Thrale there was no rest possible, even when the last field had been cleared and the last clumsily-built stack of straw or unthrashed corn erected. Besides the necessity for some form of thatching — or, failing efficiency in that direction, for completing the thrashing operations — he had to turn his attention to the immensely difficult problem of turning the grain into flour. He knew vaguely that the grain ought to be cleaned and conditioned before grinding, and that the actual separation of the constituents of the berry was a matter of importance; but he had no practical knowledge of the various operations, and in this matter Miss Oliver was quite unable to help him.

The mill beside the lock presented itself as an intricate and enormously detailed problem which must be solved by a concentrated effort of induction. The only person who appeared to be of real assistance to him was Eileen, and she was apt to tire and fall into despair when the detail of involved and often concealed machinery baffled them for hour after hour. Nevertheless Thrale solved this problem also. His first concern was for a head of water. The weirs had not been touched since the beginning of May, and the river was very low, but by mid-September there was enough water to work for a few hours every day, and, despite endless mistakes and setbacks, the mill was turning out a sufficient supply of fairly respectable looking flour.

Thrale had that wonderful masculine faculty for thus applying himself to a mechanical problem, and, like his predecessors in mechanical invention, it was the problem and not any promise of future reward which interested him. He became absorbed for the time in that problem of grinding corn, grudging the hours he was obliged to devote to other activities; and when he felt the throb of life running through the mill, saw the women he had taught attending each to their own appointed task in the economy, and felt the touch of the fine, smooth flour between his fingers, he needed no thanks from the committee nor promise of independence to reward him for his labour. The sight of this thing he had created was sufficient recompense. He loved this beautiful efficient toy that changed wheat into flour, and oats into meal, it was his to father and to fight for; the perfect child of his ingenuity and toil.

But if Thrale’s time was tremendously occupied the women found that they had more opportunities for leisure after harvest. They were still employed in field and garden, and there was still much to be done, but their hours were shorter and the work seemed light in contrast with the heroic labour that had been necessary at the harvest.

And with this first coming of comparative ease, this first opportunity for reflection since the terrible plague had thrust upon them the necessity for fierce and unremitting effort to produce the essentials of life, women began to express themselves in their various ways. Aspirations and emotions that had been crushed by the fatigues of physical labour began to revive; personal inclinations, jealousies and resentments became manifest in the detail of intercourse; old prejudices, religious and social, once more assumed an aspect of importance in the interactions of individuals. There was a faint stir in the community, the first sign of a trouble which was steadily to increase as winter laid its bond upon the storehouses of earth.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”