1775-84: Ironic Idealists

By:

February 5, 2013

According to the influential generational periodizers William Strauss and Neil Howe, a so-called Compromise Generation was born between 1767–1791. Like Strauss and Howe’s invented Silent Generation, the Compromise cohort is an “adaptive” type of generation, Strauss and Howe would have us believe; its members are risk-averse, conformist, indecisive — they’re wimps who don’t defy authority. The only meaningful evidence offered for this characterization is the fact that Kentucky politician Henry Clay has been called “the Great Compromiser,” because he brokered important compromises during the Nullification Crisis and on the slavery issue. (Strauss and Howe fail to mention that Abraham Lincoln called Clay his “beau ideal of a statesman.”) In fact, there is no such thing as the Compromise Generation!

Men and women born from 1785-94, who were in their teens and 20s during the Seventeen-Nineties (1795-1804, not to be confused with the 1790s), and in their 20s and 30s during the Eighteen-Oughts (1805-14, not to be confused with the 1800s), are instead members of the generational cohort I call the Ironic Idealists. As for the rest of the bogus and unconvincing “Compromise Generation,” they’re either New Romantics (1765-74) or Original Prometheans (1785-94).

The Ironic Idealists weren’t politically radical, like their immediate juniors and seniors — however, this does not mean they were risk-averse and indecisive. In this, they’re more like the so-called Silent Generation (1925–42) than Strauss and Howe recognize. The Anti-Anti-Utopians (1934-43), I’ve pointed out elsewhere, vociferously and articulately refused to accept the postwar consensus that there was no longer any alternative to liberal capitalism; they were neither utopian nor anti-utopian. As for the “silence” of the Postmodernists (1924–1933), I’ve argued that it was “the strategic silence of sappers and miners, undermining the enemy’s fortress; or of prisoners tunneling their way to freedom.” The Ironic Idealists tend to be a conflicted cohort, true… but in a wise and productive way.

Here are a few productively conflicted members of the Ironic Idealist Generation in whom I’m particularly interested: Jane Austen, Stendhal, E.T.A. Hoffmann, Heinrich von Kleist, Beau Brummell, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, Ingres, and Thomas Love Peacock (honorary).

A reminder of my 250-year generational periodization scheme:

1755-64: [Republican Generation] Perfectibilists

1765-74: [Republican, Compromise Generations] Original Romantics

1775-84: [Compromise Generation] Ironic Idealists

1785-94: [Compromise, Transcendental Generations] Original Prometheans

1795-1804: [Transcendental Generation] Monomaniacs

1805-14: [Transcendental Generation] Autotelics

1815-24: [Transcendental, Gilded Generations] Retrogressivists

1825-33: [Gilded Generation] Post-Romantics

1834-43: [Gilded Generation] Original Decadents

1844-53: [Progressive Generation] New Prometheans

1854-63: [Progressive, Missionary Generations] Plutonians

1864-73: [Missionary Generation] Anarcho-Symbolists

1874-83: [Missionary Generation] Psychonauts

1884-93: [Lost Generation] Modernists

1894-1903: [Lost, Greatest/GI Generations] Hardboileds

1904-13: [Greatest/GI Generation] Partisans

1914-23: [Greatest/GI Generation] New Gods

1924-33: [Silent Generation] Postmodernists

1934-43: [Silent Generation] Anti-Anti-Utopians

1944-53: [Boomers] Blank Generation

1954-63: [Boomers] OGXers

1964-73: [Generation X, Thirteenth Generation] Reconstructionists

1974-82: [Generations X, Y] Revivalists

1983-92: [Millennial Generation] Social Darwikians

1993-2002: [Millennials, Generation Z] TBA

LEARN MORE about this periodization scheme | READ ALL generational articles on HiLobrow.

ANTI-ANTI-ROMANTICISM

The Ironic Idealists occupy a funny position vis-a-vis Romanticism, the counter-Enlightenment artistic and intellectual movement that transformed the stage, the novel, poetry, painting, sculpture, ballet, and all forms of serious music beginning in the 1770s (in England and Germany) and went mainstream in the 1820s. Romanticism’s themes — a deep appreciation of the beauty of nature, a preoccupation with the heroic ideal, an embrace of emotion over reason and of the senses over intellect, and authenticity-mongering in the form of obsession with folk culture (which involved sentimentalizing the poor) and national and ethnic origins (which, eventually, would turn political in the form of nationalism) — were tarnished, for the Ironic Idealists, by the French Revolution. Yet unlike the Original Romantics (e.g., Coleridge, Wordsworth, and Southey), because they’d never rejected the Enlightenment in the first place, they didn’t violently swing back again to the opposite extreme. They retained Romanticism’s skepticism towards the Enlightenment values of rationality, order, and restraint; but — unlike second-wave Romantics (e.g., Byron, Keats, Shelley) they were also skeptical about Romanticism’s values of emotional exuberance, unrestrained imagination, and spontaneity in art and personal life. They are a No-Wave cohort.

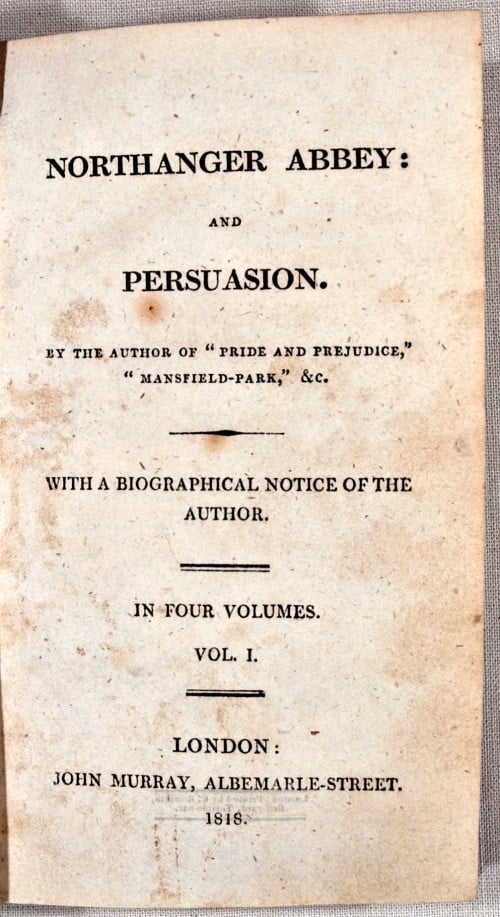

Ironic Idealists didn’t believe — with the Romantics — that radical reconstruction was possible not only in social life but in culture and art; yet neither were they cynical or apathetic. Theirs was a passionate, engaged form of irony. Jane Austen, for example, pokes fun at the ultra-romanticism of gothic literature in Northanger Abbey, in which a heroine is led astray by Mysteries of Udolpho (a novel by Ann Radcliffe, from Romanticism’s first wave). The glorification of personal emotions, the idealization of the loved one — Austin was skeptical about this sort of thing. But who would ever accuse her of being cynical, apathetic, “silent”?

Unlike their immediate elders and juniors, Ironic Idealists are funny! Austen is merely the best-known example. Thomas Love Peacock’s 1831 satirical novel Crotchet Castle is an early Argonaut Folly in which a motley crowd of “perfectibilians, deteriorationists, statu-quo-ites, phrenologists, transcendentalists, political economists, theorists in all sciences, projectors in all arts, morbid visionaries, romantic enthusiasts, lovers of music, lovers of the picturesque and lovers of good dinners” gather at the titular estate.

Though best known as author of the novella on which the Nutcracker ballet is based, the multitalented E.T.A. Hoffmann deserves to be remembered as a pioneer in the self-parodying, uncanny fantasy genre. Hoffmann’s spliced novel The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr (1819–1821) subverts Romantic idealism while celebrating artistic genius. He influenced Poe, Gogol, Baudelaire, Dostoevsky, and Kafka; his stories “Automata” and “The Sand-Man” are required reading for robot aficionados; and his “Madame de Scudery” is an early detective story.

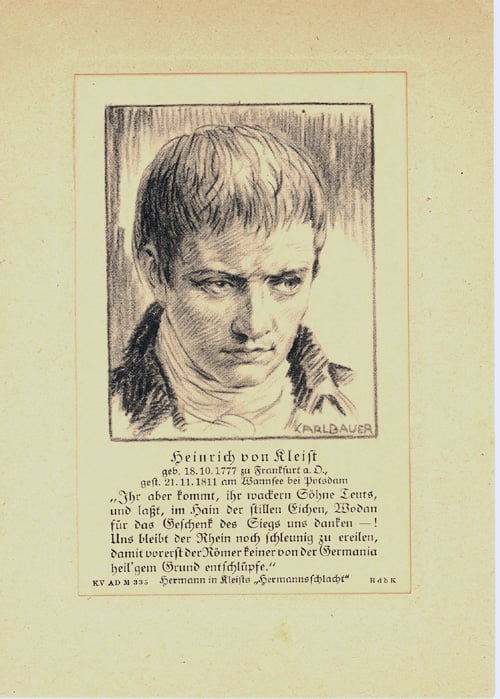

German dramatist Heinrich von Kleist and French novelist Stendhal are also frequently described as Romanticists. Both, however, subvert clichéd ideas of Romantic longing and themes of nature and innocence. Kleist’s plays show individuals in moments of crises and doubt, with both tragic and comic outcomes; Stendhal maintains a tension between clear-headed analysis and romantic feeling in his novels.

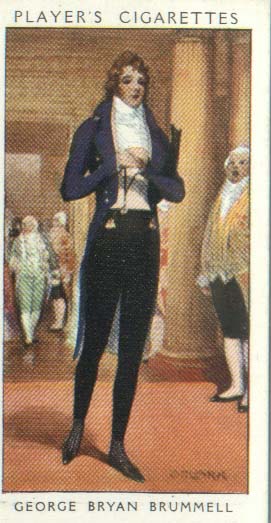

In philosophy, meanwhile, we find Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, who was regarded in his lifetime as a personality (eager, powerful) of the true Romantic type, yet whose philosophy sought to reconcile idealism and realism. And then there’s Beau Brummell, who inspired an anti-Romantic cult of artificiality (a reaction against romantic naturalism inspired by Barbey d’Aurevilly’s 1845 biography of Brummell) yet whose mode of dandyism wasn’t a flamboyant one. He was no macaroni; Brummell’s revolt against uniformity, mediocrity, and vulgarity was exquisitely self-contained.

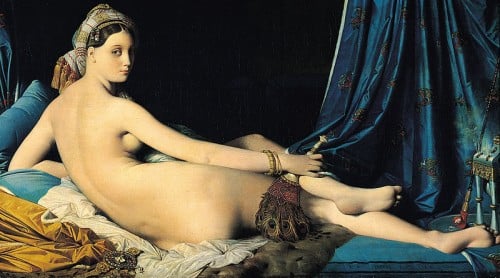

The French painter Ingres was denounced by Romantics as an unimaginative Classicist, overly dependent on art-historical precedent; yet Baudelaire would later praise Ingres for having painted “a population of automatons that disturbs our senses by its all too visible and palpable strangeness.” His practice of deliberate exaggeration inspired Degas and Picasso; however, unlike these avant-garde artists, Ingres couched his distortions in a conservative visual language of superlative draughtsmanship and authoritative brushmarks. Like Beau Brummell, Ingres’ revolt against mediocrity was stealthy — exquisitely self-contained.

Meet the Ironic Idealists.

HONORARY IRONIC IDEALISTS (cuspers born 1774): Abner Kneeland (American freethinker), Louis-Philippe (king of France, 1830-48).

1775 (cuspers): Jane Austen (Author, Horatian satirist, Pride and Prejudice), Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling (Philosopher, Naturphilosophie), Daniel O’Connell (Politician, Irish hero, called The Liberator), Francis Cabot Lowell (industrialist), Eugène François Vidocq (Criminal-turned-criminologist), André-Marie Ampère (Physicist, explored electromagnetism), William Henry (Chemist, Henry’s Law), Charles Lamb (Author, Essays of Elia), Étienne Louis Malus (Physicist, Polarization of light by reflection). HONORARY NEW ROMANTICS: J. M. W. Turner (Painter, Romanticist English landscape painter).

1776: E.T.A. Hoffmann (German author of fantasy and horror, Menippean satirist), Amedeo Avogadro (Physicist, Avogadro’s number), Hester Lucy Stanhope (adventurer), Jean-Pierre Boyer (President of Haiti, 1818-43), John Constable (English landscape painter).

1777: Heinrich von Kleist (German poet, dramatist, novelist; romantic and ironic), Tsar Alexander I (Tsar of Russia, 1801-25), Philipp Otto Runge (German romantic painter), Henry Clay (American statesman and orator), Carl Friedrich Gauss (Perhaps the greatest German mathematician), Hans Christian Oersted (Physicist, discovered electromagnetics).

1778: Beau Brummell (Dandy, 19th c. arbiter of fashion), Humphry Davy (Leading early 19th century chemist), Ugo Foscolo (Playwright), Joseph Grimaldi (Celebrated English clown), William Hazlitt (English literary critic, essayist), James Kirke Paulding (Novelist).

1779: Anacreon Moore (Irish poet, singer, songwriter, considered Ireland’s national bard; best remembered for the lyrics of The Minstrel Boy and The Last Rose of Summer; responsible for burning Byron’s memoirs after his death.), Washington Allston (Painter, Boston neighborhood named for him), Adam Müller (German economic romanticist), Jöns Jacob Berzelius (Inventor of modern chemical notation), Francis Scott Key (Poet, The Star-Spangled Banner), Clement Clarke Moore (Poet, ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas), Peter Mark Roget (Roget’s Thesaurus)

1780: Edward Hicks (Painter, The Peaceable Kingdom), Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (Painter), William Ellery Channing (Unitarian minister), Charles Nodier (French author who introduced a younger generation of Romanticists to the conte fantastique, gothic literature, vampire tales, and the importance of dreams as part of literary creation), Thomas Chalmers (Free Church of Scotland), Joseph Morgan (Patriarch of the Morgan family of millionaires), Carl von Clausewitz (Military, On War)

1781: Andrés Bello (South American intellectual, poet), Robert Hare (Hydrostatic blow-pipe and spiritoscope), René Laënnec (Stethoscope), Robert Mills (Architect, Washington Monument), Siméon-Denis Poisson (Mathematician, Poisson distribution), Sir Stamford Raffles (Founder of Singapore), John Walker (Invented the friction match).

1782: Charles Robert Maturin (Irish Protestant clergyman, writer of gothic plays and novels; Melmoth the Wanderer combines themes of Anti-Catholicism with an outcast Byronic hero), John C. Calhoun (US Vice President, champion of the South), Elihu Embree (Abolitionist and lifelong slaveholder), Samuel Guthrie (Discovered chloroform), Niccolo Paganini (Italian violinist and composer), Martin Van Buren (8th US President), Daniel Webster (Politician, “The completest man”)

1783: Simón Bolívar (Venezuelan patriot, revolutionary leader and statesman), Stendhal (dandy, ironic/romantic/realist author, Le Rouge et le Noir, La Chartreuse de Parme), Washington Irving (American author, Legend of Sleepy Hollow), William Colgate (toothpaste empire builder).

1784 (cuspers): Zachary Taylor (12th President of the United States), Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (German mathematician and astronomer), Christopher Hansteen (Studied terrestrial magnetism), Ferdinand VII (King of Spain), Lord Palmerston (Twice Prime Minister of UK). HONORARY ORIGINAL PROMETHEANS: Leigh Hunt (British critic, essayist, poet).

HONORARY IRONIC IDEALISTS (cuspers born 1785): Thomas de Quincey (English writer, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater), Thomas Love Peacock (English satirist, novelist: Nightmare Abbey).