Goslings (7)

By:

October 19, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the seventh installment of our serialization of J.D. Beresford’s Goslings (also known as A World of Women). New installments will appear each Friday for 23 weeks.

When a plague kills off most of England’s male population, the proper bourgeois Mr. Gosling abandons his family for a life of lechery. His daughters — who have never been permitted to learn self-reliance — in turn escape London for the countryside, where they find meaningful roles in a female-dominated agricultural commune. That is, until the Goslings’ idyll is threatened by their elders’ prejudices about free love!

J.D. Beresford’s friend the poet and novelist Walter de la Mare consulted on Goslings, which was first published in 1913. In May 2013, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of the book. “A fantastic commentary upon life,” wrote W.L. George in The Bookman (1914). “Mr. Beresford possesses the rare gift of divination,” wrote The Living Age (1916). “It is piece of the most vivid imaginative realism, as well as a challenge to our vaunted civilization.” “At once a postapocalyptic adventure, a comedy of manners, and a tract on sexual and social equality, Goslings is by turns funny, horrifying, and politically stirring,” says Benjamin Kunkel in a blurb for HiLoBooks. “Most remarkable of all may be that it has not yet been recognized as a classic.”

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23

Thrale joined him at the window. “Panic,” he said. “Senseless, hysterical panic. It won’t last.”

“I think I shall go out of London,” said Gurney. “I’d sooner… I’d sooner die in the country, I think.” He withdrew from the window and began to pace up and down the room again.

“Going to stampede with the rest of ’em?” asked Thrale. “Extraordinarily infectious thing, panic.”

“I don’t think it’s that exactly…” hesitated Gurney.

“Animal fear,” said Thrale. “The terror of the wild thing threatened with the unknown. The runaway horse terrified and rushing to its own destruction. Fly, fly, fly from the threat of peril as you did once on the prairies, when to fly meant safety.”

“It’s so infernally depressing in London,” said Gurney.

“All right, go and brood on death in the country,” replied Thrale. “That may cheer you up a bit. But, take my advice, don’t run. Walk at a snail’s pace and check the least tendency to hurry. Once you begin to quicken your pace, you will find yourself hurrying desperately and then stampede the hell of terror at your heels. After all, you know, you may survive. It isn’t likely that every man will die.”

Gurney caught eagerly at that. “No, no, of course it isn’t,” he said. “But wouldn’t one be much more likely to survive if one were living in the country, or by the sea in some fairly isolated place, for example. I meant to go down to Cornwall for my holiday this year, to a little cottage on the coast about four miles from Padstow; don’t you think in pure air and healthy surroundings like that, one would stand a better chance?”

“Very likely,” said Thrale carelessly. “But don’t run. In any case you’d better wait till the middle of the week. The first rush will be over then.”

“Yes. Perhaps. I’ll go on Wednesday, or Tuesday….”

Thrale smiled grimly. “Well, good night,” he said. “I’m going to bed.”

When he had gone, Gurney went to the window again. The sounds of riot from Piccadilly had died down to a low, confused murmur. A motor-car whizzed by along Jermyn Street, and two people passed on foot, a man and a woman; the woman was leaning heavily on the man’s arm.

Gurney turned once more to his pacing of the room. He was trying to realize the unrealizable fact that the world offered no refuge. For a full hour he struggled with himself, with that new, strange instinct which rose up and urged him to fly for his life. At last weary and overborne he threw himself into a chair by the dying fire and began to cry like a lost child; even as Ernst, the waiter, had cried….

4

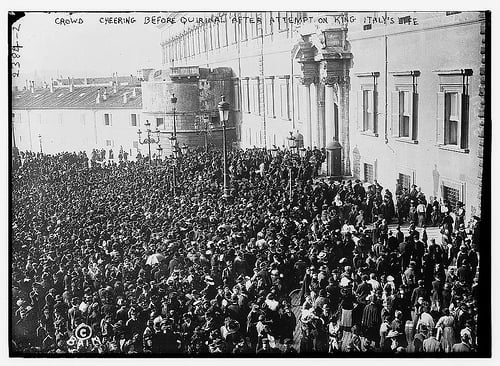

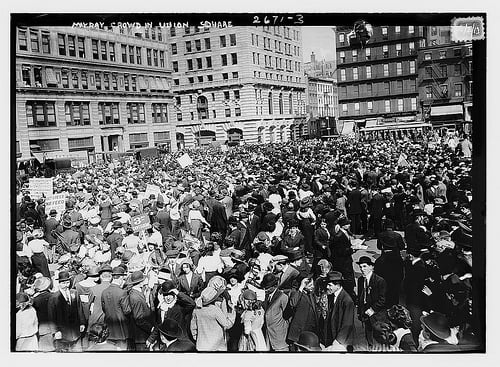

The panic emigration lasted until Monday evening, and then came news which checked and stayed the rush for the ports of Liverpool, Southampton and Queenstown. The plague was already in America. It had come, as Thrale had prophesied from the West. At the docks many of those favoured emigrants who had secured berths, hesitated; if it was to be a choice between death in America and death in England, they preferred to die at home.

Yet, even on Tuesday morning, when doubt as to the coming of the plague was no longer possible, when Dundee could only give approximate figures of the seizures in that town, reporting them as not less than a thousand, when it was evident that the whole of Scotland was becoming infected with incredible rapidity, and two cases were notified as far south as Durham, there remained still an enormous body of people who stoutly maintained that, bad as things were, the danger was grossly exaggerated, who believed that the danger would soon pass, and who, steadfast to the habits of a lifetime, continued their routine wherever it was possible so to do, determined to resist to the last.

To this body, possibly some two-fifths of the whole urban population, was due the comparative maintenance of law and order. In face of the growing destitution due to the wholesale closing of factories, warehouses and offices, necessitated by the now complete cessation of foreign trade and to the hoarding of food stores and gold which was already so marked as to have seriously affected the commerce not dependent on foreign sellers and buyers, a semblance of ordinary life was still maintained. Newspapers were issued, trains and ’buses were running, theatres and music-halls were open, and many normal occupations were carried on.

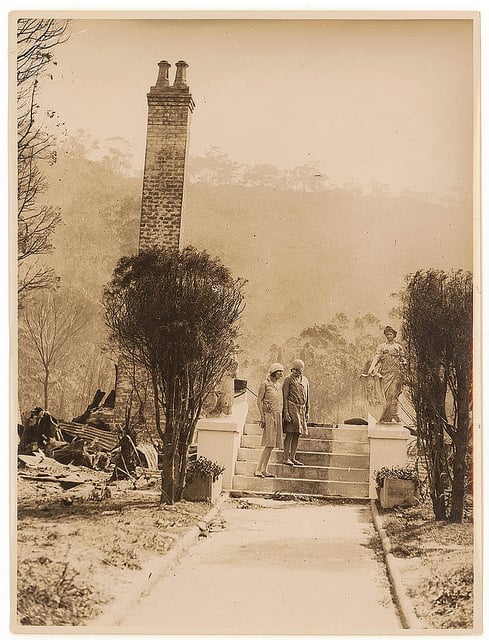

Yet everything was infected. It was as if the cloak of civilization was worn more loosely. Crime was increasing and justice was relaxed. Robberies of food were so common that there was no place for the confinement of those who were convicted. Shopkeepers were becoming at once more reliant upon their own defences, and less scrupulous in their dealings with bona-fide customers. No longer could the protection of the State be exclusively relied upon, the citizen was becoming lost in the individual. Public opinion was being resolved into individual opinion; and with the failing of the great restraint every man was developing an unsuspected side of his character. Thrown upon his own resources, he became continually less civilized, more conscious of possibilities to fulfill long-thwarted tendencies and desires; he began to understand that when it is a case of sauve qui peut, the weakest are trampled under foot.

So the cloak of civilization gaped and showed the form of the naked man, with all its blemishes and deformities. And women blenched and shuddered. For woman, as yet, was little, if at all, altered in character by the fear that was brutalizing man. Her faith in the intrinsic rectitude of the beloved conventions was more deeply rooted. Moreover woman fears the strictures of woman, more than man fears the judgments of man.

VIII

GURNEY IN CORNWALL

1

Gurney’s alternative to flying from the plague was to run away from himself. He shirked the issue in his conversations with Thrale, shuffled, sophisticated, and in a futile endeavour to convince his companion, convinced himself that his reasoning was sound and his motive unprejudiced.

It was not until the following Thursday, however, that he took train to Cornwall. He had succeeded in realizing between two and three hundred pounds in gold, and this he took with him. He intended to lay in stores of flour, sugar and other primary necessities; to buy and keep two or three cows, to rear chickens, to grow as much garden produce as possible, especially potatoes; and generally to provide against the coming scarcity of food and the cessation of transport.

The bungalow on the shores of Constantine Bay, to which he departed, was a place well suited to the carrying out of these prudent arrangements. It belonged to a friend of his, who was rich enough to indulge his whims, and who had spent a considerable sum of money in building the place and enclosing ground, but who rarely occupied the bungalow himself, and was too careless to bother about letting it. Gurney had the keys in his possession. When he had asked his friend for permission to spend his summer holiday there, he had been told to use the place as if it were his own. “Jolly good thing for me, you know,” his friend had said. “Keep it dry and all that.”

Gurney was not an idle man. Arrived at his bungalow, he lost no time in carrying out the arrangements he had schemed, and for nearly three weeks he was so absorbed in this work, in learning new occupations and perfecting his plan, that he did, indeed, achieve his purpose of running away from himself.

He became imbued with a new feeling of security; he received neither letters nor papers from the outside, and the old labourer who assisted him in setting potatoes, who taught him to milk a cow and instructed him generally in the primitive arts of self-supporting toil, seemed to regard all rumours of the new plague which filtered through to the village of St Merryn as some foreign nonsense which had little bearing on life in the county of Cornwall, as represented by the twenty-five or thirty square miles which were to him all the essential world.

Gurney began to believe that the plague would never cross the Tamar, and one day in early May, when his provisions against a seige were practically completed, he was stirred to attempt a journey across the peninsula in order to visit an acquaintance in East Looe. Gurney had become conscious of a longing for some companionship. Old Hawken was very good at cows and potatoes, but he was rather deaf and his range of ideas was severely restricted.

2

From Padstow to Looe is not an ideal journey by rail at the best of times, involving as it does, a change of train at Wadebridge, Bodmin Road and Liskeard; but Gurney was in no hurry, and the conversations he overheard in his compartment were not destructive of his new-found complacency. There was, indeed, some mention of the plague, but only in relation to the scarcity of food supply and its effect on trade. One passenger, very obviously a farmer, was congratulating himself that he was getting higher prices for stock than he had ever known, and that as luck would have it he had sown an unusual number of acres with wheat that year. “I’ll be gettun sixty or seventy a quarter, sure ’nough,” he boasted.

Dickenson —Gurney’s friend in Looe — regarded the matter more seriously, but he, too, seemed untouched by any fear of personal infection. He was an ardent Liberal, and his chief cause for concern seemed to be that the plague should have come at a time when so much progress was being made with legislation. He was, also, very distressed at the reports of poverty and starvation which abounded, and at the terrible blow to trade generally. But he seemed hopeful that the trouble would pass and be followed by a new era of enlightened government, founded on sound Liberal principles.

Gurney stayed the night and the greater part of the next day at Looe.

3

On his return journey he had to wait at Liskeard to pick up the main line train for London, which would take him to Bodmin Road.

It was a glorious May evening. The day had been hot, but now there was a cool breeze from the sea, and the long shadow from the high bank of the cutting enwrapped the whole station in a pleasant twilight.

Gurney, deliberately pacing the length of the platform, was conscious of physical vigour and a great enjoyment of life. He had an imaginative temperament, and in his moments of exaltation he found the world both interesting and beautiful, an entirely desirable setting for the essential Gurney.

So he strolled up and down the platform, regarded any female figure with interest, and was in no way concerned that the train was already an hour late. He had expected it to be late. His own train from Looe, for no particular reason, had been half an hour late. If he missed his connexion at Wadebridge he would only have some seven or eight miles to walk.

Fifteen or twenty other people were waiting on the down platform, and presently Gurney became conscious that his fellow-passengers were no longer detached into parties of two and three, but were collected in groups, discussing, apparently, some matter of peculiar interest.

Gurney had been lost in his dreams and had hardly noticed the passage of time. He looked at his watch and found that the train was now two hours overdue. The sun had set, but there was still light in the sky. A man detached himself from one of the groups and Gurney approached him.

“Two hours late,” he remarked by way of introducing himself, and looked at his watch again.

The man nodded emphatically. “Funny thing is,” he said, “that they’ve had no information at the office. The stationmaster generally gets advice when the train leaves Plymouth.”

“Good lord,” said Gurney. “Do you mean to say that the train hasn’t got to Plymouth yet?”

“Looks like it,” said the stranger. “They say it’s the plague. It’s dreadfully bad in London, they tell me.”

“D’you mean it’s possible the train won’t come in at all?” asked Gurney.

“Oh! I should hardly think that,” replied the other. “Oh, no, I should hardly think that, but goodness knows when it will come. Very awkward for me. I want to get to St Ives. It’s a long way from here. Have you far to go?”

“Well, Padstow,” said Gurney.

“Padstow!” echoed the stranger. “That’s a good step.”

“Further than I want to walk.”

“I should say. Thirty miles or so, anyway?”

“About that,” agreed Gurney. “I wonder where one could get any information.”

“It’s very awkward,” was all the help the stranger had to offer.

Gurney crossed the line and invaded the stationmaster’s office. “Sorry to trouble you,” he said, “but do you think this train’s been taken off, for any reason?”

“Oh, it ’asn’t been taken off,” said the stationmaster with a wounded air. “It may be a bit late.”

Gurney smiled. “It’s something over two hours behind now, isn’t it?” he said.

“Well, I can’t ’elp it, can I?” asked the stationmaster. “You’ll ’ave to ’ave patience.”

“You’ve had no advice yet from Plymouth?” persisted Gurney, facing the other’s ill-temper.

“No, I ’aven’t; something’s gone wrong with the wire. We can’t get no answer,” returned the stationmaster. “Now, if you please, I ’ave my work to do.”

Gurney returned to the down platform and joined a group of men, among whom he recognized the man he had spoken to a few minutes before.

The afterglow was dying out of the sky, in the south-west a faint young moon was setting behind the high bank of the cutting. A porter had lighted the station lamps, but they were not turned full on.

“The stationmaster tells me that something has gone wrong with the telegraphic communication,” said Gurney, addressing the little knot of passengers collectively. “He can’t get any answer it seems.”

“Been an accident likely,” suggested some one.

“Or the engine-driver’s got the plague,” said another.

“They’d have put another man on.”

“If they could find one.”

“If we ain’t careful we shall be gettin’ the plague down ’ere.”

After all why not? The horrible suggestion sprang up in Gurney’s mind with new force. That remote city seemed suddenly near. He saw in imagination the train leaving Paddington, and only a journey of six or seven hours divided that departure from its arrival at Liskeard. It might come in at any moment, bearing the awful infection. Why should he wait? There was an inn near the station. He might find a conveyance there.

“Constantine Bay?” questioned the landlord.

“It’s near St Merryn,” said Gurney, but still the landlord shook his head.

“Not far from Padstow,” explained Gurney.

“Pard-stow!” exclaimed the landlord on a rising note. “Drive over to Pard-stow at this time o’ night?” He appeared to think that Gurney was joking.

“Well, Bodmin, then,” suggested Gurney.

“Aw, why not take the train?” asked the landlord.

Gurney shrugged his shoulders. “The train doesn’t seem to be coming,” he said.

“Bad job, that,” answered the landlord. “Been an accident, sure ’nough; this new plague or something.” He was evidently prepared to accept the matter philosophically.

“You can’t drive me then?” asked Gurney.

The landlord shook his head with a grin. He was inclined to look upon this foreigner as rather more foolish than the majority of his kind.

Gurney came out of the little inn, and looked down into the station. The number of waiting passengers seemed to be decreasing, but the light was so dim that he could not see into the shadows.

“I must keep hold of myself,” he was saying. “I mustn’t run.”

A man was coming up the steep incline towards him, and Gurney moved slowly to meet him. He found that it was the stranger he had spoken to on the platform.

“Any news?” asked Gurney.

“Yes, they’ve got a message through from Saltash,” replied the stranger. “It’s the plague right enough. They say they don’t know when there’ll be another train….”

4

Days grew into weeks, and still there were no trains. Trade was at a standstill, and the prices of home produce mounted steadily. Fish there was, but not in great abundance, and the towns inland, such as Truro and Bodmin, organized a motor service with coast fishing villages, a service which only lasted for a week, by reason of the failure of the petrol supply. After that there was a less effective horse service.

Within three weeks after that last train arrived from outside, a new system of exchange was coming into vogue. In this little congeries of communities in Cornwall, men were beginning to learn the uselessness of gold, silver and bronze coins as tokens. Credit had collapsed, and a system of barter was being introduced, mainly between farmer and fisherman. In time it was possible that Cornwall might have become a self-supporting community, for its proportionately few inhabitants were rapidly being depleted by want and starvation; but, although it was the last place in the British Isles to become infected, the plague came there, too, in the end.

A steamer sent out from Cardiff on a plundering expedition carried the plague to the Scillies, and a fishing vessel from St Ives carried it on to Newlyn….

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”