De Condimentis (15): Gravy Bastard

By:

August 11, 2012

This is the fifteenth installment in Tom Nealon’s acclaimed and apophenic food history series De Condimentis.

You know that feeling of confusion you so often get while pouring gravy on your mashed potatoes (or your turkey if you are of that peculiar breed)? The Platonic ideal of gravy that exists in your head is not matched by the thick, brown reality at the end of your fork. Poking at an unintegrated sphere of flour, you feel an atavistic revulsion — which is spurred by an unspoken, unspeakable knowledge that there must be more than this. All the talk, the deglazing, the basting, the additives must lead somewhere other than here.

You’re not going crazy, nor are you alone. The soul of gravy is in jeopardy, and has been — increasingly so — for centuries.

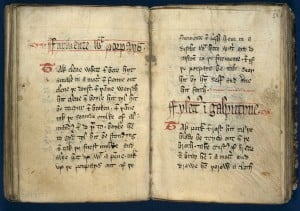

Before the advent of roasting, when boiling or cooking over a fire were the primary methods of food preparation, gravy was necessarily a different creature. In the Middle English recipe collection The Forme of Cury (The Forms of Cooking, c. 1390), a recipe for Connynges in Grauey (rabbit in gravy) is instructive:

Take Connynges smyte hem to pecys. parboile hem and drawe hem with a gode broth with almandes blanched and brayed. do þerinne sugur and powdour gynger and boyle it and the flessh þerwith. flour it with sugur and with powdour gynger an serue forth.

Now, The Forme of Cury certainly wasn’t representative of the English table at the time — it was the cookbook of the chief cook for King Richard II — but judging from other period recipes, its use of the word gravy was typical. Recipes in this vein continue for some time with a charming addition: any half-hearted or false attempts at gravy come to be called “gravy bastard.” For example, in cookbooks from this era you’ll find a recipe for “Oysters in Gravy” next to a recipe for “Oysters in Gravy Bastard.” Today, we are not only condemned to eating the latter most of the time, but we don’t realize it’s not real gravy.

Gravy was very clearly a sauce, not a condiment. Though it wasn’t called gravy until a bit later, a more obvious precursor to rabbit broth thickened with ground almonds are the meat juices and blood in baked savory pies.

These juices were so vital — and so highly regarded — that cooks, cooks’ assistants and gravy robbers actually ran a racket that involved draining the gravy out of the bottom of savory pies (“letting blood”) and selling the ill-gotten juices for use elsewhere as a condiment. The thieves would heat up a meat pie, drill small holes in its base, drain the gravy, then recork the pie for a later reheating. Don’t believe it? The cook in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (ca. 1390s) is just such a larcenist:

For many a pastee hastow laten blood

and many a Jakke of Dovere hastow sold

That hath been twice hoot and twice cold

( — Prologue to the Cook’s Tale)

Dover is thieves’ cant for do-over; a Jack of Dover might be an expensive bottle of wine refilled with plonk; or a pie that had been cooked more than once. (In a secondary sense, it came to mean an old story, or a hashed-up anecdote.) Roger the cook’s tale is a fragment, and when offered an opportunity to tell another, Roger drunkenly falls off his horse. This ought to give you some indication of just how heartily gravy robbers were despised by the upper class. During much of the 14th century, in fact, more people were imprisoned in Newgate Prison for gravy robbery than for burglary.

Thomas More, whom Jonathan Swift claimed was “the person of the greatest virtue this kingdom ever produced,” but whom recent readers have called “a particularly nasty sadomasochistic pervert” (Jasper Ridley), was as implacable a foe of gravy robbers as he was of Protestantism. It is notable, for example, that More does not hesitate to use moralistic language when speaking of a “Jak of Parys, an evil pye twyse baken.” More, author of Utopia, intellectual and martyr for his faith, was also, like Chaucer, a member of the royal court. Their propaganda campaign against gravy robbers, and their refusal to admit to anything beyond a dry pie as the result of the thievery, is as unsurprising as it was effective.

Early modern France also distinguished between true and false gravies. In the 1393 Menagier de Paris, a line is drawn between courtly gravy which would have thickeners (unspecified) added to it, on the one hand, and peasantly broth (just the liquid from boiling dinner) on the other. Broth was versatile and would have acted as a very thin condiment for dipping. The move from trenchers (hardened slices of bread used as plates that, as you might expect, get soggy when sauced) to actual plates, and the 16th century invention of the fork, also substantially expanded gravy use. It was generally understood that gravy was a giving back of what the meat had lost in being cooked — a sort of sacred pact between man and roast.

As cooking technology changed, and Italian and French ideas of gastronomy began to percolate up into Northern Europe, gravy became more associated with the actual juices that run out of a beast while it is cooking. By the 17th century this was the accepted usage, and by 1673 when Richard Ligon described the turkeys of Barbados as “full of gravy,” gravy was being used with some poetic license. Nathan Bailey’s widely read and influential Universal Etymological English Dictionary (1721) defined gravy as “the juice that runs from flesh.” Gravy, at this moment in history, was a proper “au jus” — a direct descendent of the broth of the 14th century, but adapted to cooking methods that allowed for the use of the leavings. It was just the fat and juices, thin but very rich. Gravy was no longer a sauce.

Everyman’s natural and primordial “gravy” had, for the moment, beaten out the complex and costly courtly gravy. Or that’s what it seemed like at the time, anyway. In fact, the thick sauce hadn’t vanished — it had wandered off to France to be refined.

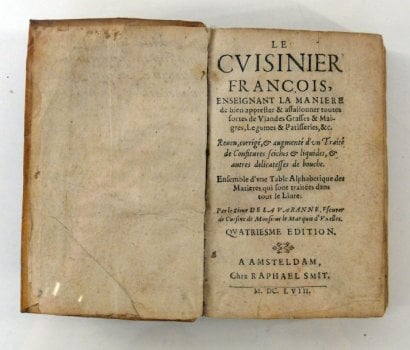

Pierre François de la Varenne’s 1651 Le Cuisinier François signaled the end (more or less) of medieval cuisine. La Varenne’s cookbook was quickly translated into English, appearing in 1653 as The French Cook and containing the first recipe for sauce Robert:

Loin of Pork with a sauce Robert

Lard it with great lard, then rost it, and baste it with verjuice and vinegar, with a bundle of sage. After the fat is fallen, take it for to fry an onion with, which being fried, you shall put it under the loin with the sauce wherewith you have basted it. All being stoved together, lest it may harden, serve.

Voilà! A piquant take on onion gravy.

New cooking technology allowed the harvesting of all of the leavings in the pan. As the 17th century progressed, and with it French cookery, normal cookery and courtly cookery separated completely, leaving “au jus” as a gravy/condiment and a series of increasingly complex sauces that served as gravy for the rich.

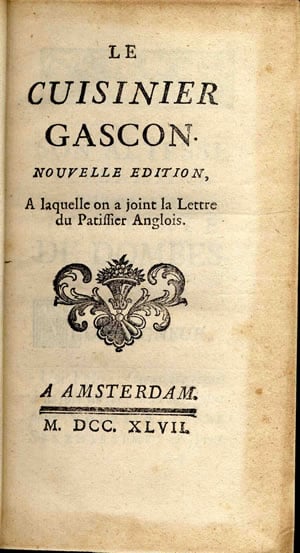

Sauce Robert eventually had mustard added to it, but the soul of this early attempt at haute gravy lived on in sauce Espagnole, though it was increasingly divorced from whatever was being gravied. Le Cuisiner Gascon (1740) gives a recipe for sauce Espagnole as: reduce two veal medallions, a slice of ham, two Partridges or Partridge hens, and a bouquet of fresh herbs, with a tablespoon of coulis (which is an 8 pound ham reduced into a half a cup of essence), a few spices and a lemon into a thick, dark, homogeneous sauce. Sauce Espagnole was tweaked over the next century, but this is still the essentials. Meat was being dressed with another meat’s juices. Some cried heresy, some just cried, and others flung themselves from parapets, bridges and under carriages — but it was no use. France was littered with the corpses of chefs who could not adapt, but cuisine surged forward. Sauce Espagnole eventually became so rarefied, so far reduced and concentrated that it was too strong to eat alone, but mix it with stock and it becomes demi-glace.

The Cuisiner Gascon was written by a minor nobleman and was meant as argument and commentary as well as cookbook. In it, he mocks and embraces the excesses of 18th-century court cuisine. One recipe has him specifically mocking poor people’s gravy as he suggests a gravy for chicken that involves cooking a pair of ducks, squeezing their juices onto a chicken, and then discarding the ducks. Whether a direct cause of the French Revolution, as some experts claim, or simply emblamatic of the debauched excesses of the final Bourbon monarchs of France, this chicken with duck gravy recipe remains as shocking today as it was 272 years ago.

English gravy, meanwhile, stayed much the same. Elizabeth Raffald’s cookbook, which remained extremely popular throughout the 18th and into the 19th century, does, in obvious thrall to continental gravy sauce, suggest browning your gravy to give it a “pleasing color,” but is otherwise content to use the broth from boiled ox cheeks.

Hannah Glasse, however, in the preface to The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (by far the most influential book of English cookery into the late 19th century), first published in 1747, suggests you make gravy in the following fashion:

Take a large deep stew pan, half a pound of bacon, fat and lean together, cut the fat and lay it over the bottom of the pan; then take a pound of veal cut it into thin slices beat it well with the back of a knife lay it all over the bacon j then have six penny worth of the coarse lean part of the beef cut thin and well beat, lay a layer of it all over with some carrot then the lean of the bacon cut thin and laid over that, then cut two onions and strew over a bundle of sweet herbs, four or five blades of mace, six or seven cloves, a spoonful of whole pepper black and white together, half a nutmeg, beat a pigeon beat all to pieces lay that all over half an ounce of truffles and morels then the rest of your beef, a good crust of bread toasted very brown and dry on both sides, you may add an old cock beat to pieces; cover it close and let it stand over a flow fire two or three minutes, then pour on boiling water enough to fill the pan, cover it close and let it stew till it is as rich as you would have it.

Clearly, even modestly fancy English cookery had fallen well under the sway of French gravy. While I appreciate the substitution of bacon for coulis, a cheaper cut of veal, and pigeons for partridges, this is quite obviously a recipe for sauce Espagnole trotted out as English gravy. And in the preface to her great work of cookery, no less.

In France au jus has survived, more or less robustly, though it is often colored, and occasionally only broth or consommé. In England a proper, thin English gravy is still around, though often thickened somewhat and darkened. Gravy that has been beaten, but not destroyed, still roams the wilds of much of Europe. As disheartening as the current state of the War of the Gravies is in Europe, what happened in America was much, much worse.

Mrs. Lincoln’s Boston Cooking School Cookbook (1889), the precursor to Fannie Farmer, describes three gravies. One is a dumbed-down sauce Espagnole using consommé; another is what we now think of as American-style gravy (deglaze the fat and leavings in the roasting pan with flour and stock, cook until thick). The third gravy, however, is a radical statement of solidarity: “But there is no sauce or made gravy equal to the natural juices contained in the meat, which should flow freely into the platter when the meat is carved.” Too little, too late. Gravy was associated, in the supposedly democratic American mind, with sauce.

When the Great Depression hit, about the only thing in any sort of supply was flour — meat certainly wasn’t. Tests were commenced on how to simulate meat in the diet of starving, depressed, out-of-work Americans. Expressions and slogans linking foods with wealth were spread around by he idiom division of the Department of Agriculture: “Beans make you wealthy!” “Ride the gravy train!” “As precious as a hill of beans.” “J. Paul Getty, a true bean of an oil man.” “Whey protein will make you rise to the top!” “He sure has plenty of beans to spend!” “The rest is gravy.” Only a few of these caught on, of course.

After a series of failures with beans (though one of these lines of inquiry did lead, decades later, to the relatively well-received tofurkey), and some predictably mixed results with whey protein, Gravy Master was introduced in 1935. Caramel color, sugar, spices — with some flour and a pat of butter to make a roux, it would make a thick dark gravy. What would people put it on? This was a problem for another day, for today the poor would have gravy that looked like the finest sauce Espagnole, the most delicately balanced demi-glace, and they would poor this elixir from a bottle that somehow managed to suggest both positivist American ingenuity and no-nonsense Yankee love of pot roast.

When they added hydrolyzed yeast extract (like autolyzed yeast — the main functional ingredient in marmite) a few years later, the deal was sealed. Hydrolyzing yeast tears open the cell walls and results in free glutamates, essentially MSG, the umami flavor that makes your brain think it’s eating meat. This was gravy: thick, dark, perfect. No need for meat — America was saved.

Ironically, this democratic move that made gravy a condiment, freeing it to become something in which you might dip your fries, smother an odd biscuit, or moisten your meatloaf, also made it but a weak shadow of haute gravy. This, instead of its simple, robust self.

In the decades since, gravy’s importance has been dimmed by an influx of foreign cuisines (though the symbolic importance of gravy is echoed in New York Italians insistence on calling red sauce “gravy”) to such an extent that the US government was forced to expand their thickening program to salad dressing. Even feral offshoots like coffee gravy (where the pan is deglazed with coffee instead of stock), root beer, country gravy (which goes by a number of names, but is milk thickened with a roux), and chocolate gravy (a roux made with bacon grease plus cocoa) were all imagined under the spell of the dominant gravy — that is to say, they are likable and often delicious branches on a dead tree.

The battle still rages. Gravy has had its ups and downs and will rise again. Especially if you bear in mind the fact that when you hear “thick and rich” used as a positive descriptor for gravy, someone is fucking with you.

MORE CONDIMENTS: Series Introduction | Fish Sauce | Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc. | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.