Arik Roper Q&A

By:

July 15, 2012

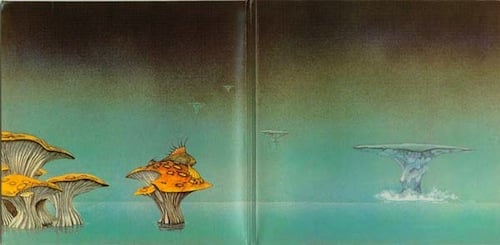

Illustration and visionary art have long been kindred spirits. Many artists belonging to the Symbolists and Decadents (art movements heavy with occult and esoteric flavor) started off as illustrators or graphic designers and many continued to incorporate these techniques into their work. This tradition continued into the twentieth century with artists such as Ernst Fuchs, H.R. Giger, and — more recently — Mark Ryden and Amanda Sage. In the Sixties, this commingling of visionary states and illustration crossed over into pop culture by way of comic books and album covers. Some of Jack Kirby’s cosmic landscapes and other-worldly machinery are as mind-altering as any Symbolist painting, and the ethereal floating islands on a Roger Dean album cover convey a similar sensibility. And then, there is Arik Roper.

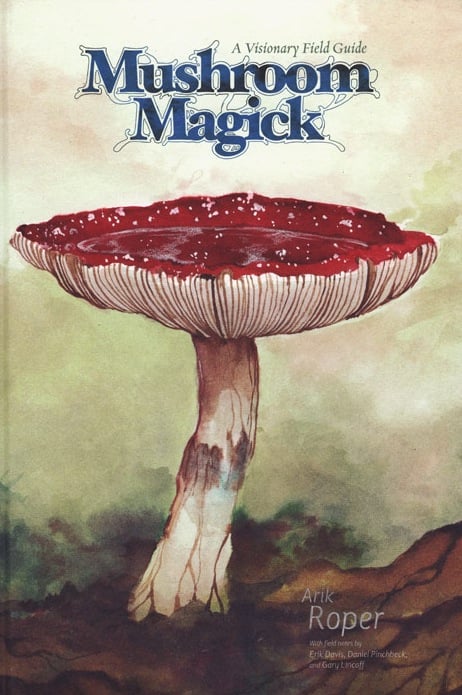

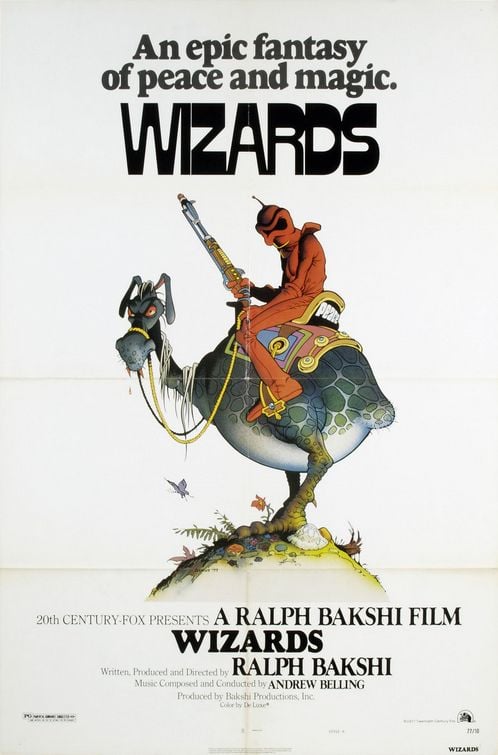

Born in 1973, Roper was influenced by magazines like Eerie and Creepy magazine, Creature Double Feature on Saturday mornings, and underground comix, not to mention prog rock, Dungeons & Dragons, and the animated films of Ralph Bakshi. Roper studied at the School of Visual Arts and quickly earned a reputation from his work with bands like Earth, Howlin’ Rain, and High on Fire. His recent cover for the reissue of Sleep’s stoner classic Dopesmoker has garnered much praise. In 2009, Roper published Mushroom Magick: A Visionary Field Guide, a beautiful collection of paintings.

I interviewed Roper for the 2011 book Too Much to Dream: A Psychedelic American Boyhood (Soft Skull Press). What follows is the complete transcript of that conversation, some of which appears in a slightly different form in the book.

PETER BEBERGAL: How did you get involved in doing the cover for the Sleep re-issue of Dopesmoker?

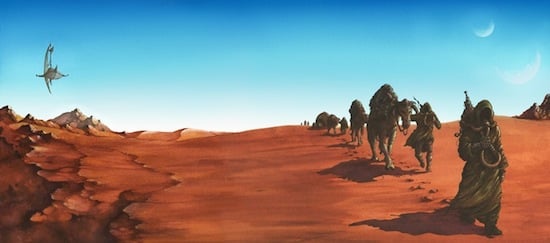

ARIK ROPER: When the rights to the Tee Pee Records version of Dopesmoker from 2003 ran out this year, Southern Lord Records jumped at the opportunity to reissue it. Al Cisneros got in touch to ask for my help in making some new art for it. We went through some ideas but we basically decided on imagery that directly related to his vision of the album. He’s a very creative artist, and his vision for Dopesmoker is an amazing piece of sci-fi fantasy, so I took inspiration from the lyrics to depict this scene of the Weedians in their caravan crossing an alien desertscape. Al was very meticulous about what he wanted so we worked closely together on it. It was collaboration, really. I was so inspired by it that I’d like to illustrate an entire story based on his mythology of this world.

PB: I’m only a few years older than you, and our influences are very much the same — things like Eerie and Creepy, Heavy Metal magazine, and Vaughn Bode’s work. How old were you when you started to come across some of these kinds of things?

AR: I was pretty young, maybe 12 or so. My father had a collection of underground and regular comics, and he was into a lot of the sci-fi and fantasy, biker graphics and things like that. So he had that around and I would see it when I was a kid, and my mother would try to hide some of it from me because it was a little too much. Actually, I think she made him throw away a whole stack of some of the material that he had.

PB: That stuff’s pretty rare.

AR: Yeah, to this day he still jokes about that. I was always into fantastic art and as a kid I used to draw pretty much the same stuff I draw now. I found a Vaughn Bode comic book at a bookstore when I was about 13 and I took it home and thought, this looks like the way I would draw if I could draw better. That laid a foundation of a style that I used to be more into, which was kind of more soft, cartoonish style. The Heavy Metal movie came out when I was about 8 and I was obsessed with it. I couldn’t see it at the time. Nobody would take me because I was eight years old. I would actually think about it a lot and then I started researching it in middle school, trying to find any info I could. I would go to the library to research animation and got into Ralph Bakshi. My dad would tell me about Wizards. He saw it in the theater when it came out and he kept telling me about it, but this was before you could get it on video. And finally, I saw Wizards, and then they played Heavy Metal on HBO and it took off from there. I started buying Heavy Metal at yard sales. I wasn’t really into superhero comics so much, but I wasn’t against them. I liked the strange stuff.

PB: What about Creepy and Eerie, Bernie Wrightson and Frazetta? I see some of Frazetta in you, particularly with the major figure in the foreground and the environmental background.

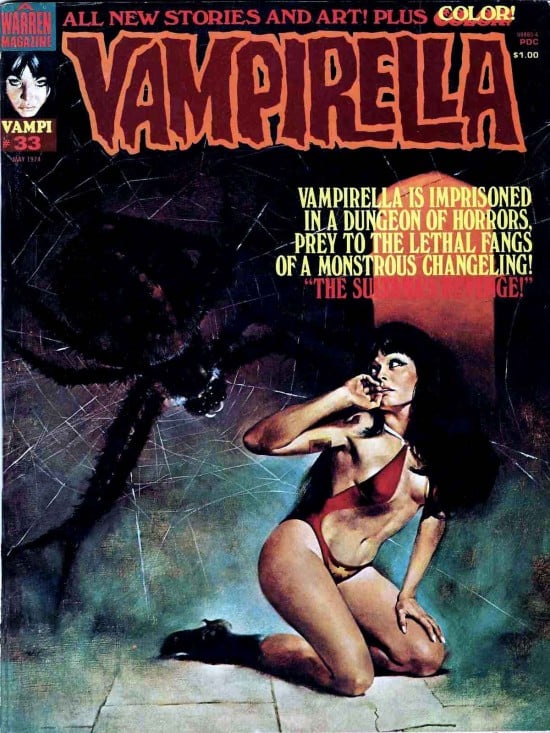

AR: I think primarily Bernie Wrightson. Frazetta was always there and of course I liked it a lot. His stuff was always just so amazing that I kind of never attempted to go there. It was just too good. That was like classical painting to me. But Bernie Wrightson was an illustrator and I really liked his forms and anatomy. I love those old Creepys and Eeries and Vampirella. The artwork’s really phenomenal. It’s consistently better than Heavy Metal, which is often really terrible.

PB: So what kind of kid were you at that time? Were you playing D&D? Were you listening to Black Sabbath?

AR: I wasn’t actually playing D&D, because I didn’t have the patience to learn the rules. But I was into collecting the figures and the books. I was the imagery more than the substance of the game. I liked the concept of it. Then I was into records a lot. I started buying records for the covers. I was into Jethro Tull and Black Sabbath and Pink Floyd. I started getting really into the album artwork and Roger Dean especially.

PB: When did you start to understand that what you were doing had some kind of connection to visionary artists?

AR: I think when I was a little older, like 19 or 20 or something, I started eating mushrooms — as much as I could get my hands on. I was really into them. They bring out these natural patterns in nature and there’s this kind of fabric or web you can see as part of your visual field and so forth. I started drawing this stuff that I was seeing, this texture, this kind of organic root pattern that I was seeing or getting from the mushrooms. It was the first time I was doing something abstract and I was trying to realize this thing that I had seen from the psilocybin. I wasn’t trying to do any kind of narrative character or anything like that. I was really trying to express this pattern and this vibe that I was getting from it. I started doing that and then I started incorporating that into the background and coloring of a lot of my work. This kind of washy sky and another textured pattern that I used to do more. I think that was probably the conception of that, as far as I can tell. I was trying to replicate this experience. Then another type of thing that would come up with acid, which had its own personality, a certain arrangement of lines. I started to see these different flavors of style with different chemicals.

PB: And was there one that appealed to you more than the others?

AR: I liked the mushroom thing more I guess. I just found that it was a bit easier in a lot of ways. Easier than the other chemicals. Softer on the system. That was the one that I was more into but I recognized it, and I see it in other art too — even really old art that people tapped into or somehow conjured. I guess you can get into it if you just really study your art or your craft. I don’t know what leads people to get this kind of similar aesthetic that I see.

PB: I know you see Jim Woodring as an influence. He was having visions as a child even before he ever had taken psychedelics. He said the psychedelics that he experimented with later only backed up what he had already experienced as a child. In a way, he was able to kind of bypass drugs as a tool because he’d already had those kind of visionary experiences without them.

AR: As a kid it kind of comes naturally, especially if you’re a creative person. Children are more in touch with it. Maybe it does remind me of something else that I was really familiar and ancient to me anyway. But Woodring really hits a vein, I think, with this stuff. It’s just so eerily reminiscent of this other part of the mind which I usually get from something like DMT. That’s what it really looks like. When I was a kid I probably wouldn’t relate it to that, but looking at it as an adult, it just kind of looks like it comes from that dimension entirely.

PB: But when I think about your work and his work compared to somebody like Alex Gray, yours is so remarkably earthy, I might even say pagan — not in the Wiccan sense — but a sort of earth-centered vision rather than this kind of cosmic, Eastern exploding consciousness vision. You work is more grounded rather than transcendent.

AR: It’s what I started doing with the earthiness of the mushroom experience. I think it’s getting back to the source, which is kind of the ultimate place to be because it’s the same as the outside. Looking inward is just as infinite as looking outward. To me, the really old ancient forms and roots and mountains and rocks and trees appeal to me more as this kind of connection to the inside of what we are an untapped history of knowledge that we have inside ourselves. It represents the inward instead of the outward. The outward is a little more obvious, I think. It’s always moving forward and going out and exploring the stars and moving out and looking for something out there. In reality, there might be stuff out there, but if you look inside, this is what you always have access to. You can’t always look outside, you can’t always go out there and look, physically, but you can always look inside and I think that you can go just as far inside as outside. For me that’s kind of the aesthetic that inspires me. It’s all here and it’s all inside and all this stuff exists in a microcosm.

PB: Sometimes in your work where there are foreground or main figures I get the sense that they are simply part of the landscape rather than the painting being about the them specifically. How do you understand the relationship between the two?

AR: That’s an unconscious compositional decision for the most part, but I have noticed it too. I often think of my characters as growing out of their environment, whether they’re mushrooms or monsters, the natural environment is bigger than they are. They’re not dominating the landscape they’re emerging from or dissolving back into it, maybe even overwhelmed by it.

PB: I think that what you’re also willing to do in your work is show that sometimes there are monsters in there, that sometimes there’s things lurking that are not always the beatific vision but rather a little bit scary and creepy, things that burrow up from under the ground.

AR: Yeah. I don’t really believe that evil exists as a separate force. I think it’s kind of relative to where you’re at, what’s evil and what’s good. All this stuff is part of the psyche and I find that really fascinating because it’s all part of us, like the shadow side. I resonate with that, and I think that addressing these things can be really healthy in realizing it’s all part of a whole. What some people would call “scary” or “sinister” to me is kind of thrill because I’m not that way as a person. I’ve got that side of me but it’s a bit cathartic to depict it artistically, it’s like working it out. It feels like it’s exercising that part of myself instead of shutting it out. Some visionary art, especially some of the west coast, Burning Man stuff gets a little too light for my taste. It’s all about exploding fractals and a billion shimmering points of glass. Technically, it’s impressive sometimes, but it’s a little bland.

PB: Well, after awhile it sort of looks all the same. I think the thing about the inner journey is you’re much more likely to meet the personality of self than you are in the external where everybody is “one.”

AR: It can get really out there. Robert Venosa’s paintings are just mind-blowingly psychedelic in their way but it’s so alien-looking. Holy shit, you’ve got to take a lot of mescaline to see that!

PB: But at the same time, in terms of music and art, but especially in terms of music, a psychedelic underground right now seems much more focused on what you’re talking about. It is much more interior, earthy, from psychedelic folk to Earth to doom metal. Do you think there’s a reason for why in this historical moment the underground seems to have much more emphasis on interiority and earth?

AR: In general, there’s something of an entertainingly ominous vibe in the air, which I think is thrilling to embrace and accept and let it inspire you, instead of making you want to run and hide. It’s becoming more and more evident that the material world isn’t real and we sort of intellectually know this. Some people experience it through different ways but everything is kind of crumbling away and you can’t put your faith in anything out there. Religions are being shown to just be a facade, for the most part. The material institutions — banks, all that stuff — they’re failing. I think people are becoming more and more independent in the sense that they know the stuff that’s really lasting is not all the shiny objects. It’s the stuff that’s really primeval that lasts and it’s coming from the inside instead of looking out there, looking somewhere else for your salvation and thinking, this is what’s going to save us. This is what’s it’s all about and those people over there have the answer. No, it’s in here and there’s something to use that’s inside of you and this kind of heavy, dark vibe that permeates a lot of the music like doom metal, it seems like it’s a return to the primeval aspect of it.

PB: I remember when Jack Rose died I realized he’s much more of an influence for these musicians now than, say, the sitar. And that’s very telling, I think.

AR: I think that people were looking far away for their influences back in the Sixties. They were tired of the American thing. That had already burned itself out. They weren’t interested in what was going on here so much as different influences. I mean, there were Blues, Rock, and Country influences in the underground, but many wanted something exotic. And now, the stuff that was exotic back then is changing, the guru trip and all that — it’s been done, and without a lot of success in general. I don’t think that’s where people are looking for inspiration so much anymore.

PB: Well, I get impatient with the 2012 phenomena. I think it’s this kind of exterior, looking towards a kind of perfect moment rather than what you’re talking about, a more interior way of looking where in a way there might even be more responsibility.

AR: The 2012 thing is completely out of hand. Ten years ago it was a fun thing to joke about. Terence McKenna was talking about it but now it’s become such a cult. The part about it that’s potentially harmful is that if people are actually looking for that and putting things off because that’s going to be the end or the beginning of something good, then they’re not doing the work now. And we don’t need anything to give us an excuse to keep fucking off. It’s not going to come and save you. There’s no Christian rapture and there’s no 2012 rapture, it’s all just now. Don’t expect there to be some date in the future where it’s all going to happen without some work. So, yeah, it’s a distraction, I think, and it’s really unfortunate that it’s become that because I think the core truths about that are kind of hard to figure out now.

PB: You’ve already been fairly explicit and candid about your drug experiences, do you mind if I ask what kind of relationship, as you’ve gotten older, that you have with psychedelics? How do they continue to impact your work? Do you feel like you need to continue to have those kinds of experiences to continue to be the type of artist you want to be? Or do you feel like, if you never took a psychedelic again, you’ve tapped in deep enough to know how to continue?

AR: I don’t like to advertise it, but it’s already kind of a given and sort of a cliché that I would be into that sort of thing. It’s true, and I wouldn’t want to talk about it all the time and make it my platform but, at the same time, I don’t feel like it’s honest or necessary to play this game about denying that it was an influence and that it’s an important tool if a person chooses to use it. We have to get rid of this stigma that people have about it as being juvenile or easy. It’s definitely neither of those things. But I don’t do it that much anymore, just because it’s harder and harder to block out the time that I would need because I take it more seriously now. There’s more in my life now that makes it a real undertaking if I want to do something like that. And I won’t just do it anywhere, anytime, like I used to. I really take it as a ritual and I try to get a lot out of it and integrate it into my life and, if possible, in my art as well. I think it’s a really powerful tool potentially. It’s not for everybody, of course, and I don’t blame people if they can’t or don’t want to pursue that. It’s like a lot of other spiritual practices where it’s scary too, you know? I think I’ve gotten enough out of it at this point that I could keep doing what I’m doing and hopefully progress with it, if I never touch the stuff again. It’s rare to do for me, now, but I get more out of it when I do it.

CHECK OUT Joe Alterio’s Cablegate Comix | HiLobrow posts about comics and cartoonists | unpublished Kim Deitch Q&A | Peter Bebergal’s interview with Denis Kitchen |