When the World Shook (10)

By:

May 11, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the tenth installment of our serialization of H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook. New installments will appear each Friday for 24 weeks.

Marooned on a South Sea island, Humphrey Arbuthnot and his friends awaken the last two members of an advanced race, who have spent 250,000 years in a state of suspended animation. Using astral projection, Lord Oro visits London and the battlefields of the Western Front; horrified by the degraded state of modern civilization, he activates chthonic technology capable of obliterating it. Will Oro’s beautiful daughter, Yva, who has fallen in love with Humphrey, stop him in time?

“If this is pulp fiction it’s high pulp: a Wagnerian opera of an adventure tale, a B-movie humanist apocalypse and chivalric romance,” says Lydia Millet in a blurb written for HiLoBooks. “When the World Shook has it all — English gentlemen of leisure, a devastating shipwreck, a volcanic tropical island inhabited by cannibals, an ancient princess risen from the grave, and if that weren’t enough a friendly, ongoing debate between a godless materialist and a devout Christian. H. Rider Haggard’s rich universe is both profoundly camp and deeply idealistic.”

Haggard’s only science fiction novel was first published in 1919. In September 2012, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of When the World Shook, with an introduction by Atlantic Monthly contributing editor James Parker. NOW AVAILABLE FOR PRE-ORDERING!

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “‘Great heavens!’ I exclaimed, ‘here’s magic.’ ‘There’s no such thing,’ answered Bickley in his usual formula. Then an explanation seemed to strike him and he added, ‘Not magic but radium or something of the sort. That’s how the temperature was kept up. In sufficient quantity it is practically indestructible, you see. My word! this old gentleman knew a thing or two.'”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24

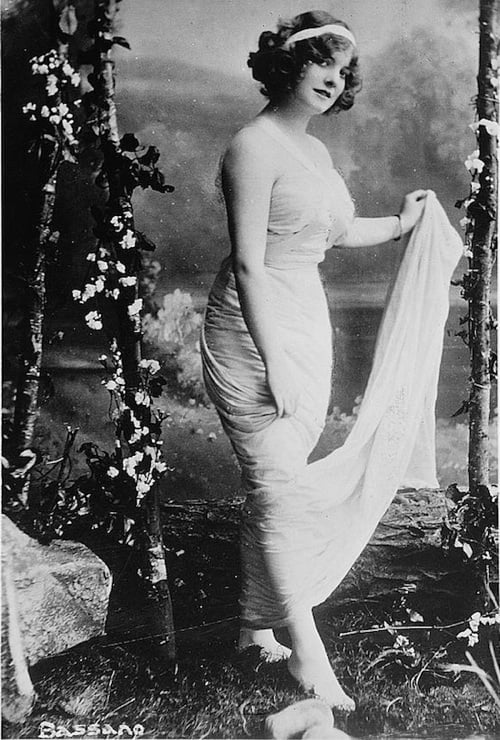

I crept round him and took my stand by the sleeper’s head, that I might watch her face, which was well worth watching, while Bickley, with his medicine at hand, remained near her feet, I think engaged in disinfecting the syringe in some spirit or acid. I believe he was about to make an attempt to use it when suddenly, as though beneath the influence of the hypnotic passes, a change appeared on the Glittering Lady’s face. Hitherto, beautiful as it was, it had been a dead face though one of a person who had suddenly been cut off while in full health and vigour a few hours, or at the most a day or so before. Now it began to live again; it was as though the spirit were returning from afar, and not without toil and tribulation.

Expression after expression flitted across the features; indeed these seemed to change so much from moment to moment that they might have belonged to several different individuals, though each was beautiful. The fact of these remarkable changes with the suggestion of multiform personalities which they conveyed impressed both Bickley and myself very much indeed. Then the breast heaved tumultuously; it even appeared to struggle. Next the eyes opened. They were full of wonder, even of fear, but oh! what marvelous eyes. I do not know how to describe them, I cannot even state their exact colour, except that it was dark, something like the blue of sapphires of the deepest tint, and yet not black; large, too, and soft as a deer’s. They shut again as though the light hurt them, then once more opened and wandered about, apparently without seeing.

At length they found my face, for I was still bending over her, and, resting there, appeared to take it in by degrees. More, it seemed to touch and stir some human spring in the still-sleeping heart. At least the fear passed from her features and was replaced by a faint smile, such as a patient sometimes gives to one known and well loved, as the effects of chloroform pass away. For a while she looked at me with an earnest, searching gaze, then suddenly, for the first time moving her arms, lifted them and threw them round my neck.

The old man stared, bending his imperial brows into a little frown, but did nothing. Bickley stared also through his glasses and sniffed as though in disapproval, while I remained quite still, fighting with a wild impulse to kiss her on the lips as one would an awakening and beloved child. I doubt if I could have done so, however, for really I was immovable; my heart seemed to stop and all my muscles to be paralysed.

I do not know for how long this endured, but I do know how it ended. Presently in the intense silence I heard Bastin’s heavy voice and looking round, saw his big head projecting into the sepulchre.

“Well, I never!” he said, “you seem to have woke them up with a vengeance. If you begin like that with the lady, there will be complications before you have done, Arbuthnot.”

Talk of being brought back to earth with a rush! I could have killed Bastin, and Bickley, turning on him like a tiger, told him to be off, find wood and light a large fire in front of the statue. I think he was about to argue when the Ancient gave him a glance of his fierce eyes, which alarmed him, and he departed, bewildered, to return presently with the wood.

But the sound of his voice had broken the spell. The Lady let her arms fall with a start, and shut her eyes again, seeming to faint. Bickley sprang forward with his sal volatile and applied it to her nostrils, the Ancient not interfering, for he seemed to recognise that he had to deal with a man of skill and one who meant well by them.

In the end we brought her round again and, to omit details, Bickley gave her, not coffee and brandy, but a mixture he compounded of hot water, preserved milk and meat essence. The effect of it on her was wonderful, since a few minutes after swallowing it she sat up in the coffin. Then we lifted her from that narrow bed in which she had slept for — ah! how long? and perceived that beneath her also were crystal boxes of the radiant, heat-giving substance. We sat her on the floor of the sepulchre, wrapping her also in a blanket.

Now it was that Tommy, after frisking round her as though in welcome of an old friend, calmly established himself beside her and laid his black head upon her knee. She noted it and smiled for the first time, a marvelously sweet and gentle smile. More, she placed her slender hand upon the dog and stroked him feebly.

Bickley tried to make her drink some more of his mixture, but she refused, motioning him to give it to Tommy. This, however, he would not do because there was but one cup. Presently both of the sleepers began to shiver, which caused Bickley anxiety. Abusing Bastin beneath his breath for being so long with the fire, he drew the blankets closer about them.

Then an idea came to him and he examined the glowing boxes in the coffin. They were loose, being merely set in prepared cavities in the crystal. Wrapping our handkerchiefs about his hand, he took them out and placed them around the wakened patients, a proceeding of which the Ancient nodded approval. Just then, too, Bastin returned with his first load of firewood, and soon we had a merry blaze going just outside the sepulchre. I saw that they observed the lighting of this fire by means of a match with much interest.

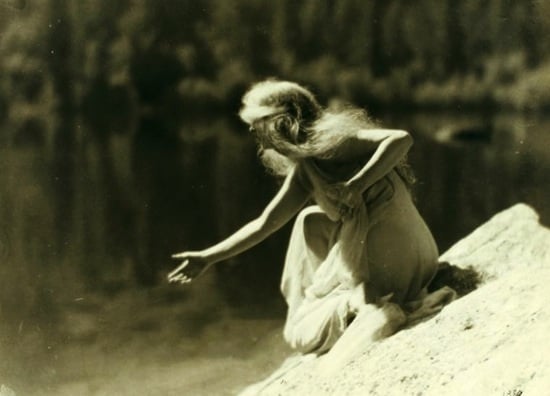

Now they grew warm again, as indeed we did also — too warm. Then in my turn I had an idea. I knew that by now the sun would be beating hotly against the rock of the mount, and suggested to Bickley, that, if possible, the best thing we could do would be to get them into its life-giving rays. He agreed, if we could make them understand and they were able to walk. So I tried. First I directed the Ancient’s attention to the mouth of the cave which at this distance showed as a white circle of light. He looked at it and then at me with grave inquiry. I made motions to suggest that he should proceed there, repeating the word “Sun” in the Orofenan tongue. He understood at once, though whether he read my mind rather than what I said I am not sure. Apparently the Glittering Lady understood also and seemed to be most anxious to go. Only she looked rather pitifully at her feet and shook her head. This decided me.

I do not know if I have mentioned anywhere that I am a tall man and very muscular. She was tall, also, but as I judged not so very heavy after her long fast. At any rate I felt quite certain that I could carry her for that distance. Stooping down, I lifted her up, signing to her to put her arms round my neck, which she did. Then calling to Bickley and Bastin to bring along the Ancient between them, with some difficulty I struggled out of the sepulchre, and started down the cave. She was more heavy than I thought, and yet I could have wished the journey longer. To begin with she seemed quite trustful and happy in my arms, where she lay with her head against my shoulder, smiling a little as a child might do, especially when I had to stop and throw her long hair round my neck like a muffler, to prevent it from trailing in the dust.

A bundle of lavender, or a truss of new-mown hay, could not have been more sweet to carry and there was something electric about the touch of her, which went through and through me. Very soon it was over, and we were out of the cave into the full glory of the tropical sun. At first, that her eyes might become accustomed to its light and her awakened body to its heat, I set her down where shadow fell from the overhanging rock, in a canvas deck chair that had been brought by Marama with the other things, throwing the rug about her to protect her from such wind as there was. She nestled gratefully into the soft seat and shut her eyes, for the motion had tired her. I noted, however, that she drew in the sweet air with long breaths.

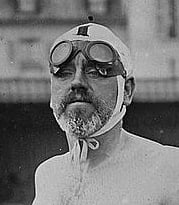

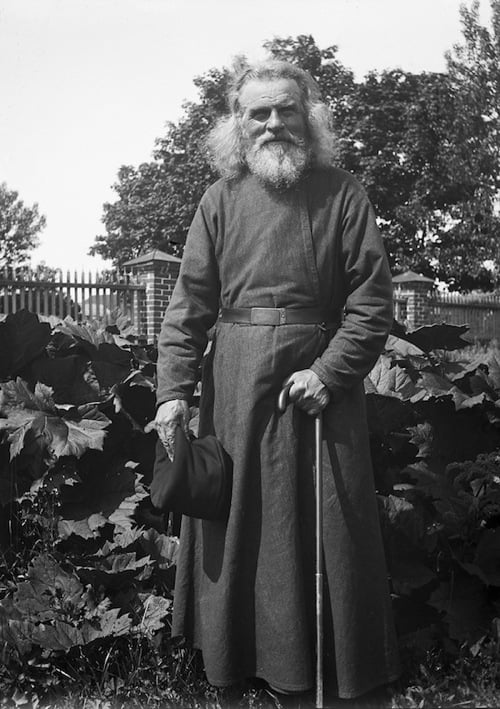

Then I turned to observe the arrival of the Ancient, who was being borne between Bickley and Bastin in what children know as a dandy-chair, which is formed by two people crossing their hands in a peculiar fashion. It says much for the tremendous dignity of his presence that even thus, with one arm round the neck of Bickley and the other round that of Bastin, and his long white beard falling almost to the ground, he still looked most imposing.

Unfortunately, however, just as they were emerging from the cave, Bastin, always the most awkward of creatures, managed to leave hold with one hand, so that his passenger nearly came to the ground. Never shall I forget the look that he gave him. Indeed, I think that from this moment he hated Bastin. Bickley he respected as a man of intelligence and learning, although in comparison with his own, the latter was infantile and crude; me he tolerated and even liked; but Bastin he detested. The only one of our party for whom he felt anything approaching real affection was the spaniel Tommy.

We set him down, fortunately uninjured, on some rugs, and also in the shadow. Then, after a little while, we moved both of them into the sun. It was quite curious to see them expand there. As Bickley said, what happened to them might well be compared to the development of a butterfly which has just broken from the living grave of its chrysalis and crept into the full, hot radiance of the light. Its crinkled wings unfold, their brilliant tints develop; in an hour or two it is perfect, glorious, prepared for life and flight, a new creature.

So it was with this pair, from moment to moment they gathered strength and vigour. Near-by to them, as it happened, stood a large basket of the luscious native fruits brought that morning by the Orofenans, and at these the Lady looked with longing. With Bickley’s permission, I offered them to her and to the Ancient, first peeling them with my fingers. They ate of them greedily, a full meal, and would have gone on had not the stern Bickley, fearing untoward consequences, removed the basket. Again the results were wonderful, for half an hour afterwards they seemed to be quite strong. With my assistance the Glittering Lady, as I still call her, for at that time I did not know her name, rose from the chair, and, leaning on me, tottered a few steps forward. Then she stood looking at the sky and all the lovely panorama of nature beneath, and stretching out her arms as though in worship. Oh! how beautiful she seemed with the sunlight shining on her heavenly face!

Now for the first time I heard her voice. It was soft and deep, yet in it was a curious bell-like tone that seemed to vibrate like the sound of chimes heard from far away. Never have I listened to such another voice. She pointed to the sun whereof the light turned her radiant hair and garments to a kind of golden glory, and called it by some name that I could not understand. I shook my head, whereon she gave it a different name taken, I suppose, from another language. Again I shook my head and she tried a third time. To my delight this word was practically the same that the Orofenans used for “sun.”

“Yes,” I said, speaking very slowly, “so it is called by the people of this land.”

She understood, for she answered in much the same language:

“What, then, do you call it?”

“Sun in the English tongue,” I replied.

“Sun. English,” she repeated after me, then added, “How are you named, Wanderer?”

“Humphrey,” I answered.

“Hum — fe — ry!” she said as though she were learning the word, “and those?”

“Bastin and Bickley,” I replied.

Over these patronymics she shook her head; as yet they were too much for her.

“How are you named, Sleeper?” I asked.

“Yva,” she answered.

“A beautiful name for one who is beautiful,” I declared with enthusiasm, of course always in the rich Orofenan dialect which by now I could talk well enough.

She repeated the words once or twice, then of a sudden caught their meaning, for she smiled and even coloured, saying hastily with a wave of her hand towards the Ancient who stood at a distance between Bastin and Bickley, “My father, Oro; great man; great king; great god!”

At this information I started, for it was startling to learn that here was the original Oro, who was still worshipped by the Orofenans, although of his actual existence they had known nothing for uncounted time. Also I was glad to learn that he was her father and not her old husband, for to me that would have been horrible, a desecration too deep for words.

“How long did you sleep, Yva?” I asked, pointing towards the sepulchre in the cave.

After a little thought she understood and shook her head hopelessly, then by an afterthought, she said,

“Stars tell Oro to-night.”

So Oro was an astronomer as well as a king and a god. I had guessed as much from those plates in the coffin which seemed to have stars engraved on them.

At this point our conversation came to an end, for the Ancient himself approached, leaning on the arm of Bickley who was engaged in an animated argument with Bastin.

“For Heaven’s sake!” said Bickley, “keep your theology to yourself at present. If you upset the old fellow and put him in a temper he may die.”

“If a man tells me that he is a god it is my duty to tell him that he is a liar,” replied Bastin obstinately.

“Which you did, Bastin, only fortunately he did not understand you. But for your own sake I advise you not to take liberties. He is not one, I think, with whom it is wise to trifle. I think he seems thirsty. Go and get some water from the rain pool, not from the lake.”

Bastin departed and presently returned with an aluminum jug full of pure water and a glass. Bickley poured some of it into a glass and handed it to Yva who bent her head in thanks. Then she did a curious thing. Having first lifted the glass with both hands to the sky and held it so for a few seconds, she turned and with an obeisance poured a little of it on the ground before her father’s feet.

A libation, thought I to myself, and evidently Bastin agreed with me, for I heard him mutter,

“I believe she is making a heathen offering.”

Doubtless we were right, for Oro accepted the homage by a little motion of the head. After this, at a sign from him she drank the water. Then the glass was refilled and handed to Oro who also held it towards the sky. He, however, made no libation but drank at once, two tumblers of it in rapid succession.

By now the direct sunlight was passing from the mouth of the cave, and though it was hot enough, both of them shivered a little. They spoke together in some language of which we could not understand a word, as though they were debating what their course of action should be. The dispute was long and earnest. Had we known what was passing, which I learned afterwards, it would have made us sufficiently anxious, for the point at issue was nothing less than whether we should or should not be forthwith destroyed — an end, it appears, that Oro was quite capable of bringing about if he so pleased. Yva, however, had very clear views of her own on the matter and, as I gather, even dared to threaten that she would protect us by the use of certain powers at her command, though what these were I do not know.

While the event hung doubtful Tommy, who was growing bored with these long proceedings, picked up a bough still covered with flowers which, after their pretty fashion, the Orofenans had placed on the top of one of the baskets of food. This small bough he brought and laid at the feet of Oro, no doubt in the hope that he would throw it for him to fetch, a game in which the dog delighted. For some reason Oro saw an omen in this simple canine performance, or he may have thought that the dog was making an offering to him, for he put his thin hand to his brow and thought a while, then motioned to Bastin to pick up the bough and give it to him.

Next he spoke to his daughter as though assenting to something, for I saw her sigh in relief. No wonder, for he was conveying his decision to spare our lives and admit us to their fellowship.

After this again they talked, but in quite a different tone and manner. Then the Glittering Lady said to me in her slow and archaic Orofenan:

“We go to rest. You must not follow. We come back perhaps tonight, perhaps next night. We are quite safe. You are quite safe under the beard of Oro. Spirit of Oro watch you. You understand?”

I said I understood, whereon she answered:

“Good-bye, O Humfe-ry.”

“Good-bye, O Yva,” I replied, bowing.

Thereon they turned and refusing all assistance from us, vanished into the darkness of the cave leaning upon each other and walking slowly.

TWO HUNDRED AND FIFTY THOUSAND YEARS!

“You seem to have made the best of your time, old fellow,” said Bickley in rather a sour voice.

“I never knew people begin to call each other by their Christian names so soon,” added Bastin, looking at me with a suspicious eye.

“I know no other,” I said.

“Perhaps not, but at any rate you have another, though you don’t seem to have told it to her. Anyway, I am glad they are gone, for I was getting tired of being ordered by everybody to carry about wood and water for them. Also I am terribly hungry as I can’t eat before it is light. They have taken most of the best fruit to which I was looking forward, but thank goodness they do not seem to care for pork.”

“So am I,” said Bickley, who really looked exhausted. “Get the food, there’s a good fellow. We’ll talk afterwards.”

When we had eaten, somewhat silently, I asked Bickley what he made of the business; also whither he thought the sleepers had gone.

“I think I can answer the last question,” interrupted Bastin. “I expect it is to a place well known to students of the Bible which even Bickley mentions sometimes when he is angry. At any rate, they seem to be very fond of heat, for they wouldn’t part from it even in their coffins, and you will admit that they are not quite natural, although that Glittering Lady is so attractive as regards her exterior.”

Bickley waved these remarks aside and addressed himself to me.

“I don’t know what to think of it,” he said; “but as the experience is not natural and everything in the Universe, so far as we know it, has a natural explanation, I am inclined to the belief that we are suffering from hallucinations, which in their way are also quite natural. It does not seem possible that two people can really have been asleep for an unknown length of time enclosed in vessels of glass or crystal, kept warm by radium or some such substance, and then emerge from them comparatively strong and well. It is contrary to natural law.”

“How about microbes?” I asked. “They are said to last practically for ever, and they are living things. So in their case your natural law breaks down.”

“That is true,” he answered. “Some microbes in a sealed tube and under certain conditions do appear to possess indefinite powers of life. Also radium has an indefinite life, but that is a mineral. Only these people are not microbes nor are they minerals. Also, experience tells us that they could not have lived for more than a few months at the outside in such circumstances as we seemed to find them.”

“Then what do you suggest?”

“I suggest that we did not really find them at all; that we have all been dreaming. You know that there are certain gases which produce illusions, laughing gas is one of them, and that these gases are sometimes met with in caves. Now there were very peculiar odours in that place under the statue, which may have worked upon our imaginations in some such way. Otherwise we are up against a miracle, and, as you know, I do not believe in miracles.”

“I do,” said Bastin calmly. “You’ll find all about it in the Bible if you will only take the trouble to read. Why do you talk such rubbish about gases?”

“Because only gas, or something of the sort, could have made us imagine them.”

“Nonsense, Bickley! Those people were here right enough. Didn’t they eat our fruit and drink the water I brought them without ever saying thank you? Only, they are not human. They are evil spirits, and for my part I don’t want to see any more of them, though I have no doubt Arbuthnot does, as that Glittering Lady threw her arms round his neck when she woke up, and already he is calling her by her Christian name, if the word Christian can be used in connection with her. The old fellow had the impudence to tell us that he was a god, and it is remarkable that he should have called himself Oro, seeing that the devil they worship on the island is also called Oro and the place itself is named Orofena.”

“As to where they have gone,” continued Bickley, taking no notice of Bastin, “I really don’t know. My expectation is, however, that when we go to look tomorrow morning — and I suggest that we should not do so before then in order that we may give our minds time to clear — we shall find that sepulchre place quite empty, even perhaps without the crystal coffins we have imagined to stand there.”

“Perhaps we shall find that there isn’t a cave at all and that we are not sitting on a flat rock outside of it,” suggested Bastin with heavy sarcasm, adding, “You are clever in your way, Bickley, but you can talk more rubbish than any man I ever knew.”

“They told us they would come back tonight or tomorrow,” I said. “If they do, what will you say then, Bickley?”

“I will wait till they come to answer that question. Now let us go for a walk and try to change our thoughts. We are all over-strained and scarcely know what we are saying.”

“One more question,” I said as we rose to start. “Did Tommy suffer from hallucinations as well as ourselves?”

“Why not?” answered Bickley. “He is an animal just as we are, or perhaps we thought we saw Tommy do the things he did.”

“When you found that basket of fruit, Bastin, which the natives brought over in the canoe, was there a bough covered with red flowers lying on the top of it?”

“Yes, Arbuthnot, one bough only; I threw it down on the rock as it got in the way when I was carrying the basket.”

“Which flowering bough we all thought we saw the Sleeper Oro carry away after Tommy had brought it to him.”

“Yes; he made me pick it up and give it to him,” said Bastin.

“Well, if we did not see this it should still be lying on the rock, as there has been no wind and there are no animals here to carry it away. You will admit that, Bickley?”

He nodded.

“Then if it has gone you will admit also that the presumption is that we saw what we thought we did see?”

“I do not know how that conclusion can be avoided, at any rate so far as the incident of the bough is concerned,” replied Bickley with caution.

Then, without more words, we started to look. At the spot where the bough should have been, there was no bough, but on the rock lay several of the red flowers, bitten off, I suppose, by Tommy while he was carrying it. Nor was this all. I think I have mentioned that the Glittering Lady wore sandals which were fastened with red studs that looked like rubies or carbuncles. On the rock lay one of these studs. I picked it up and we examined it. It had been sewn to the sandal-strap with golden thread or silk. Some of this substance hung from the hole drilled in the stone which served for an eye. It was as rotten as tinder, apparently with extreme age. Moreover, the hard gem itself was pitted as though the passage of time had taken effect upon it, though this may have been caused by other agencies, such as the action of the radium rays. I smiled at Bickley who looked disconcerted and even sad. In a way it is painful to see the effect upon an able and earnest man of the upsetting of his lifelong theories.

We went for our walk, keeping to the flat lands at the foot of the volcano cone, for we seemed to have had enough of wonders and to desire to reassure ourselves, as it were, by the study of natural and familiar things. As it chanced, too, we were rewarded by sundry useful discoveries. Thus we found a place where the bread-tree and other fruits, most of them now ripe, grew in abundance, as did the yam. Also, we came to an inlet that we noticed was crowded with large and beautiful fish from the lake, which seemed to find it a favourite spot. Perhaps this was because a little stream of excellent water ran in here, overflowing from the great pool or mere which filled the crater above.

At these finds we rejoiced greatly, for now we knew that we need not fear starvation even should our supply of food from the main island be cut off. Indeed, by help of some palm-leaf stalks which we wove together roughly, Bastin, who was rather clever at this kind of thing, managed to trap four fish weighing two or three pounds apiece, wading into the water to do so. It was curious to observe with what ease he adapted himself to the manners and customs of primeval man, so much so, indeed, that Bickley remarked that if he could believe in re-incarnation, he would be absolutely certain that Bastin was a troglodyte in his last sojourn on the earth.

However this might be, Bastin’s primeval instincts and abilities were of the utmost service to us. Before we had been many days on that island he had built us a kind of native hut or house roofed with palm leaves in which, until provided with a better, as happened afterwards, we ate and he and Bickley slept, leaving the tent to me. Moreover, he wove a net of palm fibre with which he caught abundance of fish, and made fishing-lines of the same material (fortunately we had some hooks) which he baited with freshwater mussels and the insides of fish. By means of these he secured some veritable monsters of the carp species that proved most excellent eating. His greatest triumph, however, was a decoy which he constructed of boughs, wherein he trapped a number of waterfowl. So that soon we kept a very good table of a sort, especially after he had learned how to cook our food upon the native plan by means of hot stones. This suited us admirably, as it enabled Bickley and myself to devote all our time to archaeological and other studies which did not greatly interest Bastin.

NEXT WEEK: “‘Receive the curse of Oro,’ said the Ancient again. Then followed a terrible spectacle. The man went raving mad. He bounded into the air to a height inconceivable. He threw himself upon the ground and rolled upon the rock. He rose again and staggered round and round, tearing pieces out of his arms with his teeth. He yelled hideously like one possessed. He grovelled, beating his forehead against the rock. Then he sat up, slowly choked and — died.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: You are reading H. Rider Haggard’s When The World Shook. Also read our serialization of: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail and “As Easy As A.B.C.” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.