Guy Fawkes Mask-ology

By:

April 30, 2012

Editor’s note: This is one of the most popular posts, traffic-wise, ever published on HiLobrow. Click here to see a list of the Top 25 Most Popular posts (as of October 2012); and click here for an archive of all of HILOBROW’s most popular posts.

It’s a ubiquitous image now: in pictures from Occupy Wall Street, the Arab Spring, anti-SOPA/PIPA demonstrations, you see figures in Guy Fawkes masks. Since first entering the American cultural field via the lulzy culture of Anonymous, the Guy Fawkes mask has become a potent symbolic force in political activism. In January of this year, members of the Polish parliament donned the mask in protest against their government’s support for ACTA, and images of the mask are often used in the media to illustrate stories on digital activism in general. Understanding the significance of symbols like the Guy Fawkes mask both for the groups and individuals using it, and for society and the state at large, can help us to understand how digital activism is evolving.

The Guy Fawkes mask is an old one, and its symbolic life has been complex. Guy Fawkes, the man, was one of the perpetrators of the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, an attempt by English Catholics to assassinate King James and blow up the House of Lords. November 5th has historically been known as Guy Fawkes Day or Bonfire Night in Great Britain, and is celebrated with fireworks, bonfires, and the burning of Guy Fawkes in effigy. The Guy Fawkes mask has its roots in these celebrations.

The mask and, to some extent, the historical figure of Guy Fawkes received a bit of rehabilitation via the 1982-89 comic book series V for Vendetta by Alan Moore and David Lloyd. The comic depicts a near-future Britain under the rule of a fascist dictatorship. The main character, an anarchic revolutionary known only as V, wears a stylized Guy Fawkes mask, and convinces another character, Evey, to join with him in an elaborate and violent plot to bring down the government and return political autonomy to the British people.

A film adaptation of the comic book was released in March of 2006, directed by James McTeigue and starring Natalie Portman and Hugo Weaving. (Alan Moore refused to endorse the adaptation, saying the project dampened the anarchist leanings of the original work and ignored its anti-Thatcherite message.) The film was a financial and critical success, bringing in over $130 million in its box office run. As part of the commercial merchandising of the film, Halloween costume replicas of Hugo Weaving’s V costume and mask were sold starting in September 2006, with the mask available separately for $6.99.

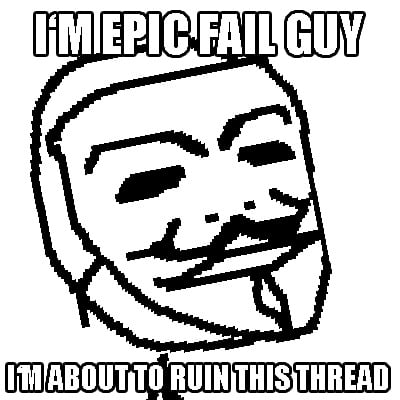

The mask as an object began its migration into modern popular-political culture on the /b/ board of 4chan, the online image board that gave rise to the group Anonymous. A character known as Epic Fail Guy, a stick figure who failed at everything, became popular on /b/ in 2006. In a collaborative cartooning style popular on the boards, threads would be posted (with single frame images contributed by many people) showing Epic Fail Guy trying to achieve some action or status and failing again and again. In late September 2006, one such thread appeared wherein Epic Fail Guy discovered what appeared to be a V for Vendetta film-type Guy Fawkes in a garbage can. Subsequently, Epic Fail Guy was often depicted wearing the mask.

It’s unclear whether this association had anything to do with the historical story of Guy Fawkes (whose Gunpowder Plot was, in fact, an EPIC FAIL), or whether it was due simply to the marketing blitz for V for Vendetta. Either way, the initial popularity of the mask within the Anonymous community was directly due to its association with Epic Fail Guy, and only indirectly (if at all) to political sympathy with either the historical Guy Fawkes or V for Vendetta.

The mask crossed over into real-world political use with Operation Chanology, an anti-Scientology international protest organized in early 2008 by Anonymous; it was a notable moment in the politicization of Anonymous. Protesters appeared outside Churches of Scientology worldwide to protest what they saw as the Church’s censorious and abusive practices. The mask’s role in Operation Chanology was two-fold. Given Scientology’s vindictive reprisals against those who challenge the church publicly, many Anons wore the mask in order to conceal their identities at the IRL protests. The secondary motive was a play off of the mask’s meaning within the Anonymous community; the use of the mask called out what Anons saw as the EPIC FAILness of Scientology. This was just one of many many inside jokes and cultural memes (including references to lolcats and earlier Anonymous raids) that peppered the Operation Chanology protests.

As Anonymous’s political identity has developed, the symbolism of the mask has shifted away from Epic Fail Man. The population involved in Anonymous actions has expanded beyond those involved with 4chan and the notorious message board /b/ to encompass activists and those involved with more mainstream internet culture. The symbolism of the mask itself, adopted by anti-authoritarian protesters from OWS to the Arab Spring, seems to have reverted to more closely embody the meaning in the V for Vendetta comics and film. Rather than overtly mocking those targeted by the protesters, the mask (an anarchic folk hero with a smile and curved mustache) serves as a political identifier. The wearer is identified as anti-authoritarian, a member of an online generation that values the freedom of communication and assembly that the internet has so powerfully enabled.

Anonymous has another iconic signature that symbolizes the group’s leaderless nature: a headless black suit with its arms folded behind it. The suit calls to mind pop culture figures like Agent Smith in The Matrix and the powerful secret agents in Men in Black — figures which represent an unknown power structure operating outside the realm of normal comprehension. Outside of the Anonymous world, however, the Anonymous empty suit hasn’t gained as much traction as the Guy Fawkes mask. The public was primed (by a major Hollywood marketing campaign) to read the Guy Fawkes as a political symbol; the empty suit lacks this external social validation. Also, it’s more difficult to show up at a real world protest dressed as an empty suit than it is to don a mask.

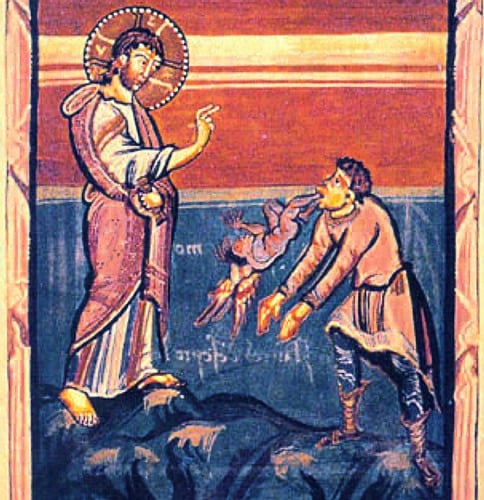

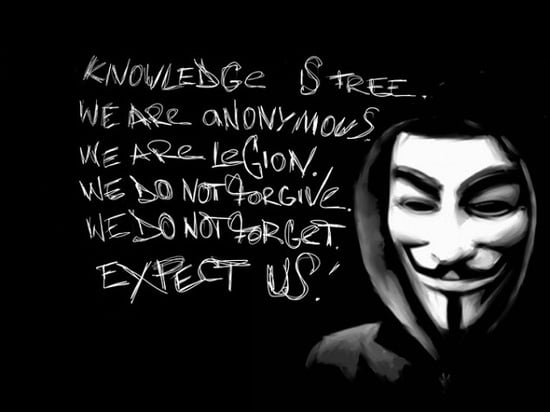

Anonymous’s conception of identity is at base a pluralistic one. The power and attraction of Anonymous is built out of the concept of the hoard, the mass, the unstoppable wave. “We are legion. We do not forgive. We do not forget. Expect us,” is the unofficial motto of Anonymous. It appears in videos, image macros, and all manner of viral media produced by and around Anonymous. The phrase “We are legion” comes from the Gospel of Mark, from the story where Jesus exorcises a demon from a possessed man. When asked for its name, the demon replies, “αὐτῷ Λεγιὼν ὄνομά μοι, ὅτι πολλοί ἐσμεν:” meaning, “I am [called] legion, for we are many.” The original phrase, perhaps better than the Anonymous adaptation, captures the peculiar nature of the Anonymous identity meme, wherein many different identities are drawn up and into a single identity. One central source is made more powerful by the participation of many individuals. But those individual identities move in and out of different states of participation. Individuals join in under the banner of Anonymous, temporarily subsuming their personalities under the larger, meta-personality of the Anonymous hoard. The mask is a signifier of that shift.

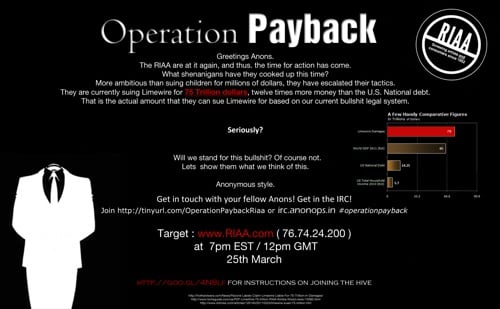

A technological parallel for this subsumation is the “Hive Mind” mode built into a version of the LOIC DDOS tool, which was popular during the Operation Payback DDOS attacks that began in September 2010. Named for a weapon used in the Command and Conquer videogame series, the Low Orbit Ion Cannon (LOIC) is an open source network stress-testing application that can perform a denial-of-service (DoS; or when used by multiple individuals, DDoS) attack on a target site. When running in Hive Mind mode (or Fucking Hive Mind mode, depending on the version you were running), rather than independently targeting and deploying the tool, you could instead place your computer under the control of a central IRC server. By joining this voluntary botnet, you were able to add your individual digital voice to the stream of other voices being controlled by an overarching persona: “I am legion, for we are many.”

In addition to its identity value, the Guy Fawkes mask also embodies a narrative value. This narrative is an aggregate one, which incorporates the various ideologies and social myths associated with the mask and Guy Fawkes himself over four centuries. Even though Anonymous may not have intended to reference Guy-Fawkes the Catholic would-be-regicide during Operation Chanology, that narrative was still present. Today, as the political use of the mask spreads beyond Anonymous to movements like Occupy Wall Street and more mainstream Internet activism, it retains its narrative associations not only with Guy Fawkes but with Operation Chanology, Operation Payback, and the Anonymous collective persona.

As the mask becomes more popular in the general population, it’s helpful to recall the communalist aspects of online communities and protest environments. A core value of Anonymous, one that grew out of the default architecture of the 4chan imageboard, is the anonymity — and thus the radical equality — of its participants. When worn by members of the Occupy movement, the mask symbolizes that movement’s message of equality and communalism. The mask also emphasizes the need for anonymity in our political system, both rhetorically and actually. As with the original protests in Operation Chanology, many participants in the Occupy movement felt that open participation could put them in danger of losing their job or suffering other social and economic consequences. Just as the ubiquitous presence of cheap cameras in the hands of civilians empowers them against the casual brutality of the police, the mask empowers the public against the so-called panopticon — the cameras of the state, or the cameras co-opted by the state. In an age in which we are dogged by social media, it is vital that there be moments when we can choose to have an anonymous voice (in the voting booth, among other places). Masked protest is in part a statement in support of anonymity, privacy.

It is perhaps tempting to view Anonymous as the Legion in the Gospel of Mark story, i.e., a corrupting — even demonic — presence within a larger structure. However, although the Anonymous identity meme does operate as a sort of possessive, incorporating force, absorbing individuals temporarily and acting as a meta-identity structure, it is by no means simply malignant. Anonymous is one face of a broad anti-authoritarian, pro-freedom sentiment; its iconic mask symbolizes both that movement’s ends, its means (individuals collected as a single entity), and the right to anonymous public political participation. The use of the Guy Fawkes mask suggests a movement with an infinitely reproducible identity, a fractal movement via which individuals or small cells can operate and act — for better or worse, hopefully the former — with the power of the whole.