With the Night Mail (4)

By:

April 11, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the fourth installment of our serialization of Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and his follow-up story, “As Easy as A.B.C.”). New installments will appear each Wednesday for 12 weeks.

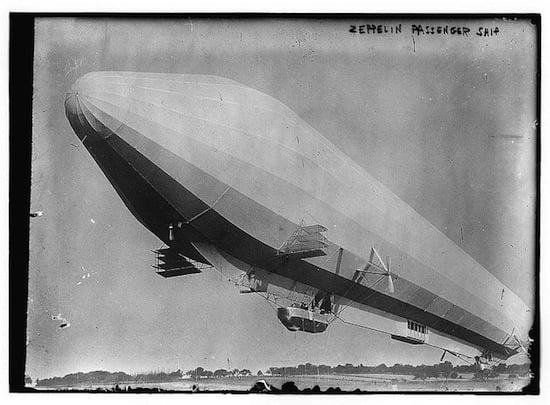

With the Night Mail follows the exploits of an intercontinental mail dirigible battling the perfect storm. Between London and Quebec we learn that a planet-wide Aerial Board of Control (A.B.C.) now enforces a technocratic system of command and control not only in the skies but in world affairs, too. A follow-up story, “As Easy As A.B.C.,” recounts what happens when agitators in Chicago demand a return of democracy: The A.B.C. sends zeppelins armed with sound weapons to subdue not the agitators, but a mob who would destroy them! With the Night Mail is set in 2000, and it first appeared in 1905; 2012 marks the centennial of the first publication of “As Easy As A.B.C.”

In June, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), checked against the 1909 first published edition (Doubleday), with an Introduction by science fiction author Matthew De Abaitua, and an Afterword by science fiction author Bruce Sterling. SUPPLIES ARE LIMITED! CLICK HERE TO ORDER YOUR COPY.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “Still the clear dark holds up unblemished. The only warning is the electric skin-tension (I feel as though I were a lace-maker’s pillow) and an irritability which the gibbering of the General Communicator increases almost to hysteria.”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12

We dropped from ten to six thousand and got rid of our clammy suits. Tim shut off and stepped out of the Frame. The Mark Boat was coming up behind us. He opened the colloid in that heavenly stillness and mopped his face.

“Hello, Williams!” he cried. “A degree or two out o’ station, ain’t you?”

“May be,” was the answer from the Mark Boat. “I’ve had some company this evening.”

“So I noticed. Wasn’t that quite a little draught?”

“I warned you. Why didn’t you pull out round by Disko? The east-bound packets have.”

“Me? Not till I’m running a Polar consumptives’ Sanatorium boat. I was squinting through a colloid before you were out of your cradle, my son.”

“I’d be the last man to deny it,” the captain of the Mark Boat replies softly. “The way you handled her just now —I’m a pretty fair judge of traffic in a volt-flurry — it was a thousand revolutions beyond anything even I‘ve ever seen.”

Tim’s back supples visibly to this oiling. Captain George on the c. p. winks and points to the portrait of a singularly attractive maiden pinned up on Tim’s telescope-bracket above the steering-wheel.

I see. Wholly and entirely do I see!

There is some talk overhead of “coming round to tea on Friday,” a brief report of the derelict’s fate, and Tim volunteers as he descends: “For an A. B. C. man young Williams is less of a high-tension fool than some… Were you thinking of taking her on, George? Then I’ll just have a look round that port-thrust — seems to me it’s a trifle warm — and we’ll jog along.”

The Mark Boat hums off joyously and hangs herself up in her appointed eyrie. Here she will stay, a shutterless observatory; a life-boat station; a salvage tug; a court of ultimate appeal-cum-meteorological bureau for three hundred miles in all directions, till Wednesday next when her relief slides across the stars to take her buffeted place. Her black hull, double conning-tower, and ever-ready slings represent all that remains to the planet of that odd old word authority. She is responsible only to the Aërial Board of Control — the A. B. C. of which Tim speaks so flippantly. But that semi-elected, semi-nominated body of a few score persons of both sexes, controls this planet. “Transportation is Civilization,” our motto runs. Theoretically, we do what we please so long as we do not interfere with the traffic and all it implies. Practically, the A. B. C. confirms or annuls all international arrangements and, to judge from its last report, finds our tolerant, humorous, lazy little planet only too ready to shift the whole burden of private administration on its shoulders.

I discuss this with Tim, sipping maté on the c. p. while George fans her along over the white blur of the Banks in beautiful upward curves of fifty miles each. The dip-dial translates them on the tape in flowing freehand.

Tim gathers up a skein of it and surveys the last few feet, which record “162’s” path through the volt-flurry.

“I haven’t had a fever-chart like this to show up in five years,” he says ruefully.

A postal packet’s dip-dial records every yard of every run. The tapes then go to the A. B. C., which collates and makes composite photographs of them for the instruction of captains. Tim studies his irrevocable past, shaking his head.

“Hello! Here’s a fifteen-hundred-foot drop at eighty-five degrees! We must have been standing on our heads then, George.”

“You don’t say so,” George answers. “I fancied I noticed it at the time.”

George may not have Captain Purnall’s catlike swiftness, but he is all an artist to the tips of the broad fingers that play on the shunt-stops. The delicious flight-curves come away on the tape with never a waver. The Mark Boat’s vertical spindle of light lies down to eastward, setting in the face of the following stars. Westward, where no planet should rise, the triple verticals of Trinity Bay (we keep still to the Southern route) make a low-lifting haze. We seem the only thing at rest under all the heavens; floating at ease till the earth’s revolution shall turn up our landing-towers.

And minute by minute our silent clock gives us a sixteen-second mile.

“Some fine night,” says Tim. “We’ll be even with that clock’s Master.”

“He’s coming now,” says George, over his shoulder. “I’m chasing the night west.”

The stars ahead dim no more than if a film of mist had been drawn under unobserved, but the deep air-boom on our skin changes to a joyful shout.

“The dawn-gust,” says Tim. “It’ll go on to meet the Sun. Look! Look! There’s the dark being crammed back over our bow! Come to the after-colloid. I’ll show you something.”

The engine-room is hot and stuffy; the clerks in the coach are asleep, and the Slave of the Ray is near to follow them. Tim slides open the aft colloid and reveals the curve of the world — the ocean’s deepest purple — edged with fuming and intolerable gold. Then the Sun rises and through the colloid strikes out our lamps. Tim scowls in his face.

“Squirrels in a cage,” he mutters. “That’s all we are. Squirrels in a cage! He’s going twice as fast as us. Just you wait a few years, my shining friend and we’ll take steps that will amaze you. We’ll Joshua you!”

Yes, that is our dream: to turn all earth into the Vale of Ajalon at our pleasure. So far, we can drag out the dawn to twice its normal length in these latitudes. But some day — even on the Equator — we shall hold the Sun level in his full stride.

Now we look down on a sea thronged with heavy traffic. A big submersible breaks water suddenly. Another and another follow with a swash and a suck and a savage bubbling of relieved pressures. The deep-sea freighters are rising to lung up after the long night, and the leisurely ocean is all patterned with peacock’s eyes of foam.

“We’ll lung up, too,” says Tim, and when we return to the c. p. George shuts off, the colloids are opened, and the fresh air sweeps her out. There is no hurry. The old contracts (they will be revised at the end of the year) allow twelve hours for a run which any packet can put behind her in ten. So we breakfast in the arms of an easterly slant which pushes us along at a languid twenty.

To enjoy life, and tobacco, begin both on a sunny morning half a mile or so above the dappled Atlantic cloud-belts and after a volt-flurry which has cleared and tempered your nerves. While we discussed the thickening traffic with the superiority that comes of having a high level reserved to ourselves, we heard (and I for the first time) the morning hymn on a Hospital boat.

She was cloaked by a skein of ravelled fluff beneath us and we caught the chant before she rose into the sunlight. “Oh, ye Winds of God,” sang the unseen voices: “bless ye the Lord! Praise Him and magnify Him forever!”

We slid off our caps and joined in. When our shadow fell across her great open platforms they looked up and stretched out their hands neighbourly while they sang. We could see the doctors and the nurses and the white-button-like faces of the cot-patients. She passed slowly beneath us, heading northward, her hull, wet with the dews of the night, all ablaze in the sunshine. So took she the shadow of a cloud and vanished, her song continuing. Oh, ye holy and humble men of heart, bless ye the Lord! Praise Him and magnify Him forever.

“She’s a public lunger or she wouldn’t have been singing the Benedicite; and she’s a Greenlander or she wouldn’t have snow-blinds over her colloids,” said George at last. “She’ll be bound for Frederikshavn or one of the Glacier sanatoriums for a month. If she was an accident ward she’d be hung up at the eight-thousand-foot level. Yes — consumptives.”

“Funny how the new things are the old things. I’ve read in books,” Tim answered, “that savages used to haul their sick and wounded up to the tops of hills because microbes were fewer there. We hoist ’em into sterilized air for a while. Same idea. How much do the doctors say we’ve added to the average life of a man?”

“Thirty years,” says George with a twinkle in his eye. “Are we going to spend ’em all up here, Tim?”

“Flap along, then. Flap along. Who’s hindering?” the senior captain laughed, as we went in.

We held a good lift to clear the coastwise and Continental shipping; and we had need of it. Though our route is in no sense a populated one, there is a steady trickle of traffic this way along. We met Hudson Bay furriers out of the Great Preserve, hurrying to make their departure from Bonavista with sable and black fox for the insatiable markets. We over-crossed Keewatin liners, small and cramped; but their captains, who see no land between Trepassy and Blanco, know what gold they bring back from West Africa. Trans-Asiatic Directs, we met, soberly ringing the world round the Fiftieth Meridian at an honest seventy knots; and white-painted Ackroyd & Hunt fruiters out of the south fled beneath us, their ventilated hulls whistling like Chinese kites. Their market is in the North among the northern sanatoria where you can smell their grapefruit and bananas across the cold snows. Argentine beef boats we sighted too, of enormous capacity and unlovely outline. They, too, feed the northern health stations in ice-bound ports where submersibles dare not rise.

Yellow-bellied ore-flats and Ungava petrol-tanks punted down leisurely out of the north like strings of unfrightened wild duck. It does not pay to “fly” minerals and oil a mile farther than is necessary; but the risks of transhipping to submersibles in the ice-pack off Nain or Hebron are so great that these heavy freighters fly down to Halifax direct, and scent the air as they go. They are the biggest tramps aloft except the Athabasca grain-tubs. But these last, now that the wheat is moved, are busy, over the world’s shoulder, timber-lifting in Siberia.

We held to the St. Lawrence (it is astonishing how the old water-ways still pull us children of the air), and followed his broad line of black between its drifting ice blocks, all down the Park that the wisdom of our fathers — but every one knows the Quebec run.

We dropped to the Heights Receiving Towers twenty minutes ahead of time and there hung at ease till the Yokohama Intermediate Packet could pull out and give us our proper slip. It was curious to watch the action of the holding-down clips all along the frosty river front as the boats cleared or came to rest. A big Hamburger was leaving Pont Levis and her crew, unshipping the platform railings, began to sing “Elsinore”— the oldest of our chanteys. You know it of course:

Forty couple waltzing on the floor!

And you can watch my Ray,

For I must go away

And dance with Ella Sweyn at Elsinore!

Then, while they sweated home the covering-plates:

West from Sourabaya to the Baltic —

Ninety knot an hour to the Skaw!

Mother Rugen’s tea-house on the Baltic

And a dance with Ella Sweyn at Elsinore!

The clips parted with a gesture of indignant dismissal, as though Quebec, glittering under her snows, were casting out these light and unworthy lovers. Our signal came from the Heights. Tim turned and floated up, but surely then it was with passionate appeal that the great tower arms flung open — or did I think so because on the upper staging a little hooded figure also opened her arms wide towards her father?

In ten seconds the coach with its clerks clashed down to the receiving-caisson; the hostlers displaced the engineers at the idle turbines, and Tim, prouder of this than all, introduced me to the maiden of the photograph on the shelf. “And by the way,” said he to her, stepping forth in sunshine under the hat of civil life, “I saw young Williams in the Mark Boat. I’ve asked him to tea on Friday.”

Thus ends With the Night Mail. Kipling also wrote extracts from the Aerial Board of Control Bulletin, a magazine of the year 2000. We will serialize these extracts beginning next week.

NEXT WEEK: “NEW ERA—It is not etiquette to overcross an A. B. C. official’s boat without asking permission. He is one of the body responsible for the planet’s traffic, and for that reason must not be interfered with. You, presumably, are out on your own business or pleasure, and should leave him alone. For humanity’s sake don’t try to be ‘democratic.'”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: You are reading Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail and “As Easy As A.B.C.” Also read our serialization of: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | H. Rider Haggard’s When The World Shook

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.