When the World Shook (3)

By:

March 23, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the third installment of our serialization of H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook. New installments will appear each Friday for 24 weeks.

Marooned on a South Sea island, Humphrey Arbuthnot and his friends awaken the last two members of an advanced race, who have spent 250,000 years in a state of suspended animation. Using astral projection, Lord Oro visits London and the battlefields of the Western Front; horrified by the degraded state of modern civilization, he activates chthonic technology capable of obliterating it. Will Oro’s beautiful daughter, Yva, who has fallen in love with Humphrey, stop him in time?

“If this is pulp fiction it’s high pulp: a Wagnerian opera of an adventure tale, a B-movie humanist apocalypse and chivalric romance,” says Lydia Millet in a blurb written for HiLoBooks. “When the World Shook has it all — English gentlemen of leisure, a devastating shipwreck, a volcanic tropical island inhabited by cannibals, an ancient princess risen from the grave, and if that weren’t enough a friendly, ongoing debate between a godless materialist and a devout Christian. H. Rider Haggard’s rich universe is both profoundly camp and deeply idealistic.”

Haggard’s only science fiction novel was first published in 1919. In September 2012, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of When the World Shook, with an introduction by Atlantic Monthly contributing editor James Parker. NOW AVAILABLE FOR PRE-ORDERING!

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “That is what we thought, if we thought at all. Certainly we never dreamed of a precipice. Why should we, who were young, by comparison, quite healthy and very rich? Who thinks of precipices under such circumstances, when disaster seems to be eliminated and death is yet a long way off?”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24

I am bound to say that when we returned home to Fulcombe, where of course we met with a great reception, including the ringing (out of tune) of the new peal of bells that I had given to the church, Bastin made haste to point this out.

“Your wife seems a very nice and beautiful lady, Arbuthnot,” he reflected aloud after dinner, when Mrs. Bastin, glowering as usual, though what at I do not know, had been escorted from the room by Natalie, “and really, when I come to think of it, you are an unusually fortunate person. You possess a great deal of money, much more than you have any right to; which you seem to have done very little to earn and do not spend quite as I should like you to do, and this nice property, that ought to be owned by a great number of people, as, according to the views you express, I should have thought you would acknowledge, and everything else that a man can want. It is very strange that you should be so favoured and not because of any particular merits of your own which one can see. However, I have no doubt it will all come even in the end and you will get your share of troubles, like others. Perhaps Mrs. Arbuthnot will have no children as there is so much for them to take. Or perhaps you will lose all your money and have to work for your living, which might be good for you. Or,” he added, still thinking aloud after his fashion, “perhaps she will die young — she has that kind of face, although, of course, I hope she won’t,” he added, waking up.

I do not know why, but his wandering words struck me cold; the proverbial funeral bell at the marriage feast was nothing to them. I suppose it was because in a flash of intuition I knew that they would come true and that he was an appointed Cassandra. Perhaps this uncanny knowledge overcame my natural indignation at such super-gaucherie of which no one but Bastin could have been capable, and even prevented me from replying at all, so that I merely sat still and looked at him.

But Bickley did reply with some vigour.

“Forgive me for saying so, Bastin,” he said, bristling all over as it were, “but your remarks, which may or may not be in accordance with the principles of your religion, seem to me to be in singularly bad taste. They would have turned the stomachs of a gathering of early Christians, who appear to have been the worst mannered people in the world, and at any decent heathen feast your neck would have been wrung as that of a bird of ill omen.”

“Why?” asked Bastin blankly. “I only said what I thought to be the truth. The truth is better than what you call good taste.”

“Then I will say what I think also to be the truth,” replied Bickley, growing furious. “It is that you use your Christianity as a cloak for bad manners. It teaches consideration and sympathy for others of which you seem to have none. Moreover, since you talk of the death of people’s wives, I will tell you something about your own, as a doctor, which I can do as I never attended her. It is highly probable, in my opinion, that she will die before Mrs. Arbuthnot, who is quite a healthy person with a good prospect of life.”

“Perhaps,” said Bastin. “If so, it will be God’s will and I shall not complain” (here Bickley snorted), “though I do not see what you can know about it. But why should you cast reflections on the early Christians who were people of strong principle living in rough times, and had to wage war against an established devil-worship? I know you are angry because they smashed up the statues of Venus and so forth, but had I been in their place I should have done the same.”

“Of course you would, who doubts it? But as for the early Christians and their iconoclastic performances — well, curse them, that’s all!” and he sprang up and left the room.

I followed him.

Let it not be supposed from the above scene that there was any ill-feeling between Bastin and Bickley. On the contrary they were much attached to each other, and this kind of quarrel meant no more than the strong expression of their individual views to which they were accustomed from their college days. For instance Bastin was always talking about the early Christians and missionaries, while Bickley loathed both, the early Christians because of the destruction which they had wrought in Egypt, Italy, Greece and elsewhere, of all that was beautiful; and the missionaries because, as he said, they were degrading and spoiling the native races and by inducing them to wear clothes, rendering them liable to disease. Bastin would answer that their souls were more important than their bodies, to which Bickley replied that as there was no such thing as a soul except in the stupid imagination of priests, he differed entirely on the point. As it was quite impossible for either to convince the other, there the conversation would end, or drift into something in which they were mutually interested, such as natural history and the hygiene of the neighbourhood.

Here I may state that Bickley’s keen professional eye was not mistaken when he diagnosed Mrs. Bastin’s state of health as dangerous. As a matter of fact she was suffering from heart disease that a doctor can often recognise by the colour of the lips, etc., which brought about her death under the following circumstances:

Her husband attended some ecclesiastical function at a town over twenty miles away and was to have returned by a train which would have brought him home about five o’clock. As he did not arrive she waited at the station for him until the last train came in about seven o’clock — without the beloved Basil. Then, on a winter’s night she tore up to the Priory and begged me to lend her a dog-cart in which to drive to the said town to look for him. I expostulated against the folly of such a proceeding, saying that no doubt Basil was safe enough but had forgotten to telegraph, or thought that he would save the sixpence which the wire cost.

Then it came out, to Natalie’s and my intense amusement, that all this was the result of her jealous nature of which I have spoken. She said she had never slept a night away from her husband since they were married and with so many “designing persons” about she could not say what might happen if she did so, especially as he was “such a favourite and so handsome.” (Bastin was a fine looking man in his rugged way.)

I suggested that she might have a little confidence in him, to which she replied darkly that she had no confidence in anybody.

The end of it was that I lent her the cart with a fast horse and a good driver, and off she went. Reaching the town in question some two and a half hours later, she searched high and low through wind and sleet, but found no Basil. He, it appeared, had gone on to Exeter, to look at the cathedral where some building was being done, and missing the last train had there slept the night.

About one in the morning, after being nearly locked up as a mad woman, she drove back to the Vicarage, again to find no Basil. Even then she did not go to bed but raged about the house in her wet clothes, until she fell down utterly exhausted. When her husband did return on the following morning, full of information about the cathedral, she was dangerously ill, and actually passed away while uttering a violent tirade against him for his supposed suspicious proceedings.

That was the end of this truly odious British matron.

In after days Bastin, by some peculiar mental process, canonised her in his imagination as a kind of saint. “So loving,” he would say, “such a devoted wife! Why, my dear Humphrey, I can assure you that even in the midst of her death-struggle her last thoughts were of me,” words that caused Bickley to snort with more than usual vigour, until I kicked him to silence beneath the table.

DEATH AND DEPARTURE

Now I must tell of my own terrible sorrow, which turned my life to bitterness and my hopes to ashes.

Never were a man and a woman happier together than I and Natalie. Mentally, physically, spiritually we were perfectly mated, and we loved each other dearly. Truly we were as one. Yet there was something about her which filled me with vague fears, especially after she found that she was to become a mother. I would talk to her of the child, but she would sigh and shake her head, her eyes filling with tears, and say that we must not count on the continuance of such happiness as ours, for it was too great.

I tried to laugh away her doubts, though whenever I did so I seemed to hear Bastin’s slow voice remarking casually that she might die, as he might have commented on the quality of the claret. At last, however, I grew terrified and asked her bluntly what she meant.

“I don’t quite know, dearest,” she replied, “especially as I am wonderfully well. But — but —”

“But what?” I asked.

“But I think that our companionship is going to be broken for a little while.”

“For a little while!” I exclaimed.

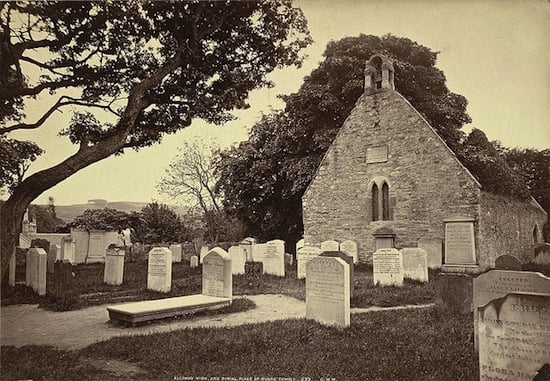

“Yes, Humphrey. I think that I shall be taken away from you — you know what I mean,” and she nodded towards the churchyard.

“Oh, my God!” I groaned.

“I want to say this,” she added quickly, “that if such a thing should happen, as it happens every day, I implore you, dearest Humphrey, not to be too much distressed, since I am sure that you will find me again. No, I can’t explain how or when or where, because I do not know. I have prayed for light, but it has not come to me. All I know is that I am not talking of reunion in Mr. Bastin’s kind of conventional heaven, which he speaks about as though to reach it one stumbled through darkness for a minute into a fine new house next door, where excellent servants had made everything ready for your arrival and all the lights were turned up. It is something quite different from that and very much more real.”

Then she bent down ostensibly to pat the head of a little black cocker spaniel called Tommy which had been given to her as a puppy, a highly intelligent and affectionate animal that we both adored and that loved her as only a dog can love. Really, I knew, it was to hide her tears, and fled from the room lest she should see mine.

As I went I heard the dog whimpering in a peculiar way, as though some sympathetic knowledge had been communicated to its wonderful animal intelligence.

That night I spoke to Bickley about the matter, repeating exactly what had passed. As I expected, he smiled in his grave, rather sarcastic way, and made light of it.

“My dear Humphrey,” he said, “don’t torment yourself about such fancies. They are of everyday occurrence among women in your wife’s condition. Sometimes they take one form, sometimes another. When she has got her baby you will hear no more of them.”

I tried to be comforted but in vain.

The days and weeks went by like a long nightmare and in due course the event happened. Bickley was not attending the case; it was not in his line, he said, and he preferred that where a friend’s wife was concerned, somebody else should be called in. So it was put in charge of a very good local man with a large experience in such domestic matters.

How am I to tell of it? Everything went wrong; as for the details, let them be. Ultimately Bickley did operate, and if surpassing skill could have saved her, it would have been done. But the other man had misjudged the conditions; it was too late, nothing could help either mother or child, a little girl who died shortly after she was born but not before she had been christened, also by the name of Natalie.

I was called in to say farewell to my wife and found her radiant, triumphant even in her weakness.

“I know now,” she whispered in a faint voice. “I understood as the chloroform passed away, but I cannot tell you. Everything is quite well, my darling. Go where you seem called to go, far away. Oh! the wonderful place in which you will find me, not knowing that you have found me. Good-bye for a little while; only for a little while, my own, my own!”

Then she died. And for a time I too seemed to die, but could not. I buried her and the child here at Fulcombe; or rather I buried their ashes since I could not endure that her beloved body should see corruption.

Afterwards, when all was over, I spoke of these last words of Natalie’s with both Bickley and Bastin, for somehow I seemed to wish to learn their separate views.

The latter I may explain, had been present at the end in his spiritual capacity, but I do not think that he in the least understood the nature of the drama which was passing before his eyes. His prayers and the christening absorbed all his attention, and he never was a man who could think of more than one thing at a time.

When I told him exactly what had happened and repeated the words that Natalie spoke, he was much interested in his own nebulous way, and said that it was delightful to meet with an example of a good Christian, such as my wife had been, who actually saw something of Heaven before she had gone there. His own faith was, he thanked God, fairly robust, but still an undoubted occurrence of the sort acted as a refreshment, “like rain on a pasture when it is rather dry, you know,” he added, breaking into simile.

I remarked that she had not seemed to speak in the sense he indicated, but appeared to allude to something quite near at hand and more or less immediate.

“I don’t know that there is anything nearer at hand than the Hereafter,” he answered. “I expect she meant that you will probably soon die and join her in Paradise, if you are worthy to do so. But of course it is not wise to put too much reliance upon words spoken by people at the last, because often they don’t quite know what they are saying. Indeed sometimes I think this was so in the case of my own wife, who really seemed to me to talk a good deal of rubbish. Good-bye, I promised to see Widow Jenkins this afternoon about having her varicose veins cut out, and I mustn’t stop here wasting time in pleasant conversation. She thinks just as much of her varicose veins as we do of the loss of our wives.”

I wonder what Bastin’s ideas of unpleasant conversation may be, thought I to myself, as I watched him depart already wool-gathering on some other subject, probably the heresy of one of those “early fathers” who occupied most of his thoughts.

Bickley listened to my tale in sympathetic silence, as a doctor does to a patient. When he was obliged to speak, he said that it was interesting as an example of a tendency of certain minds towards romantic vision which sometimes asserts itself, even in the throes of death.

“You know,” he added, “that I put faith in none of these things. I wish that I could, but reason and science both show me that they lack foundation. The world on the whole is a sad place, where we arrive through the passions of others implanted in them by Nature, which, although it cares nothing for individual death, is tender towards the impulse of races of every sort to preserve their collective life. Indeed the impulse is Nature, or at least its chief manifestation. Consequently, whether we be gnats or elephants, or anything between and beyond, even stars for aught I know, we must make the best of things as they are, taking the good and the evil as they come and getting all we can out of life until it leaves us, after which we need not trouble. You had a good time for a little while and were happy in it; now you are having a bad time and are wretched. Perhaps in the future, when your mental balance has re-asserted itself, you will have other good times in the afternoon of your days, and then follow twilight and the dark. That is all there is to hope for, and we may as well look the thing in the face. Only I confess, my dear fellow, that your experience convinces me that marriage should be avoided at whatever inconvenience. Indeed I have long wondered that anyone can take the responsibility of bringing a child into the world. But probably nobody does in cold blood, except misguided idiots like Bastin,” he added. “He would have twenty, had not his luck intervened.”

“Then you believe in nothing, Friend,” I said.

“Nothing, I am sorry to say, except what I see and my five senses appreciate.”

“You reject all possibility of miracle, for instance?”

“That depends on what you mean by miracle. Science shows us all kinds of wonders which our great grandfathers would have called miracles, but these are nothing but laws that we are beginning to understand. Give me an instance.”

“Well,” I replied at hazard, “if you were assured by someone that a man could live for a thousand years?”

“I should tell him that he was a fool or a liar, that is all. It is impossible.”

“Or that the same identity, spirit, animating principle — call it what you will — can flit from body to body, say in successive ages? Or that the dead can communicate with the living?”

“Convince me of any of these things, Arbuthnot, and mind you I desire to be convinced, and I will take back every word I have said and walk through Fulcombe in a white sheet proclaiming myself the fool. Now, I must get off to the Cottage Hospital to cut out Widow Jenkins’s varicose veins. They are tangible and real at any rate; about the largest I ever saw, indeed. Give up dreams, old boy, and take to something useful. You might go back to your fiction writing; you seem to have leanings that way, and you know you need not publish the stories, except privately for the edification of your friends.”

With this Parthian shaft Bickley took his departure to make a job of Widow Jenkins’s legs.

I took his advice. During the next few months I did write something which occupied my thoughts for a while, more or less. It lies in my safe to this minute, for somehow I have never been able to make up my mind to burn what cost me so much physical and mental toil.

When it was finished my melancholy returned to me with added force. Everything in the house took a tongue and cried to me of past days. Its walls echoed a voice that I could never hear again; in the very looking-glasses I saw the reflection of a lost presence. Although I had moved myself for the purposes of sleep to a little room at the further end of the building, footsteps seemed to creep about my bed at night and I heard the rustle of a remembered dress without the door. The place grew hateful to me. I felt that I must get away from it or I should go mad.

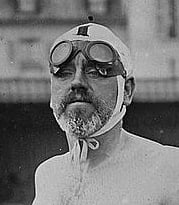

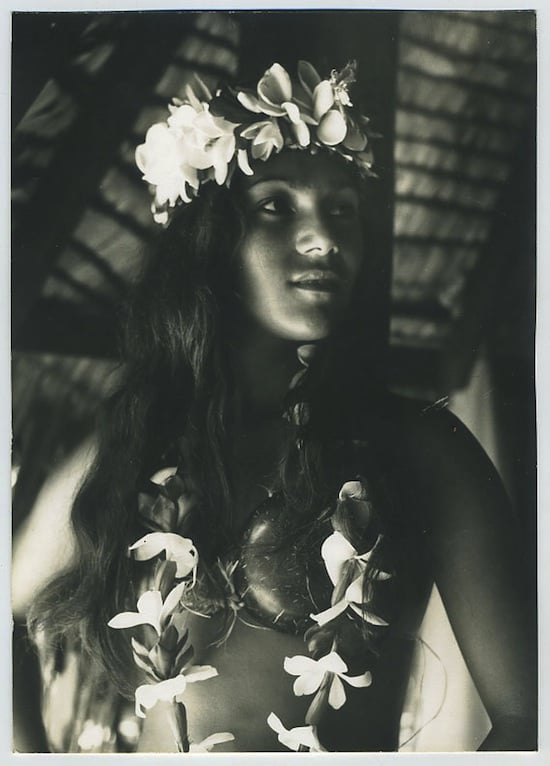

One afternoon Bastin arrived carrying a book and in a state of high indignation. This work, written, as he said, by some ribald traveller, grossly traduced the character of missionaries to the South Sea Islands, especially of those of the Society to which he subscribed, and he threw it on the table in his righteous wrath. Bickley picked it up and opened it at a photograph of a very pretty South Sea Island girl clad in a few flowers and nothing else, which he held towards Bastin, saying:

“Is it to this child of Nature that you object? I call her distinctly attractive, though perhaps she does wear her hibiscus blooms with a difference to our women — a little lower down.”

“The devil is always attractive,” replied Bastin gloomily. “Child of Nature indeed! I call her Child of Sin. That photograph is enough to make my poor Sarah turn in her grave.”

“Why?” asked Bickley; “seeing that wide seas roll between you and this dusky Venus. Also I thought that according to your Hebrew legend sin came in with bark garments.”

“You should search the Scriptures, Bickley,” I broke in, “and cultivate accuracy. It was fig-leaves that symbolised its arrival. The garments, which I think were of skin, developed later.”

“Perhaps,” went on Bickley, who had turned the page, “she” (he referred to the late Mrs. Bastin) “would have preferred her thus,” and he held up another illustration of the same woman.

In this the native belle appeared after conversion, clad in broken-down stays —I suppose they were stays — out of which she seemed to bulge and flow in every direction, a dirty white dress several sizes too small, a kind of Salvation Army bonnet without a crown and a prayer-book which she held pressed to her middle; the general effect being hideous, and in some curious way, improper.

“Certainly,” said Bastin, “though I admit her clothes do not seem to fit and she has not buttoned them up as she ought. But it is not of the pictures so much as of the letterpress with its false and scandalous accusations, that I complain.”

“Why do you complain?” asked Bickley. “Probably it is quite true, though that we could never ascertain without visiting the lady’s home.”

“If I could afford it,” exclaimed Bastin with rising anger, “I should like to go there and expose this vile traducer of my cloth.”

“So should I,” answered Bickley, “and expose these introducers of consumption, measles and other European diseases, to say nothing of gin, among an innocent and Arcadian people.”

“How can you call them innocent, Bickley, when they murder and eat missionaries?”

“I dare say we should all eat a missionary, Bastin, if we were hungry enough,” was the answer, after which something occurred to change the conversation.

But I kept the book and read it as a neutral observer, and came to the conclusion that these South Sea Islands, a land where it was always afternoon, must be a charming place, in which perhaps the stars of the Tropics and the scent of the flowers might enable one to forget a little, or at least take the edge off memory. Why should I not visit them and escape another long and dreary English winter? No, I could not do so alone. If Bastin and Bickley were there, their eternal arguments might amuse me. Well, why should they not come also? When one has money things can always be arranged.

The idea, which had its root in this absurd conversation, took a curious hold on me. I thought of it all the evening, being alone, and that night it re-arose in my dreams. I dreamed that my lost Natalie appeared to me and showed me a picture. It was of a long, low land, a curving shore of which the ends were out of the picture, whereon grew tall palms, and where great combers broke upon gleaming sand.

Then the picture seemed to become a reality and I saw Natalie herself, strangely changeful in her aspect, strangely varying in face and figure, strangely bright, standing in the mouth of a pass whereof the little bordering cliffs were covered with bushes and low trees, whose green was almost hid in lovely flowers. There in my dream she stood, smiling mysteriously, and stretched out her arms towards me.

As I awoke I seemed to hear her voice, repeating her dying words: “Go where you seem called to go, far away. Oh! the wonderful place in which you will find me, not knowing that you have found me.”

With some variations this dream visited me twice that night. In the morning I woke up quite determined that I would go to the South Sea Islands, even if I must do so alone. On that same evening Bastin and Bickley dined with me. I said nothing to them about my dream, for Bastin never dreamed and Bickley would have set it down to indigestion. But when the cloth had been cleared away and we were drinking our glass of port — both Bastin and Bickley only took one, the former because he considered port a sinful indulgence of the flesh, the latter because he feared it would give him gout —I remarked casually that they both looked very run down and as though they wanted a rest. They agreed, at least each of them said he had noticed it in the other. Indeed Bastin added that the damp and the cold in the church, in which he held daily services to no congregation except the old woman who cleaned it, had given him rheumatism, which prevented him from sleeping.

“Do call things by their proper names,” interrupted Bickley. “I told you yesterday that what you are suffering from is neuritis in your right arm, which will become chronic if you neglect it much longer. I have the same thing myself, so I ought to know, and unless I can stop operating for a while I believe my fingers will become useless. Also something is affecting my sight, overstrain, I suppose, so that I am obliged to wear stronger and stronger glasses. I think I shall have to leave Ogden” (his partner) “in charge for a while, and get away into the sun. There is none here before June.”

“I would if I could pay a locum tenens and were quite sure it isn’t wrong,” said Bastin.

“I am glad you both think like that,” I remarked, “as I have a suggestion to make to you. I want to go to the South Seas about which we were talking yesterday, to get the thorough change that Bickley has been advising for me, and I should be very grateful if you would both come as my guests. You, Bickley, make so much money out of cutting people about, that you can arrange your own affairs during your absence. But as for you, Bastin, I will see to the wherewithal for the locum tenens, and everything else.”

“You are very kind,” said Bastin, “and certainly I should like to expose that misguided author, who probably published his offensive work without thinking that what he wrote might affect the subscriptions to the missionary societies, also to show Bickley that he is not always right, as he seems to think. But I could never dream of accepting without the full approval of the Bishop.”

“You might get that of your nurse also, if she happens to be still alive,” mocked Bickley. “As for his Lordship, I don’t think he will raise any objection when he sees the certificate I will give you about the state of your health. He is a great believer in me ever since I took that carbuncle out of his neck which he got because he will not eat enough. As for me, I mean to come if only to show you how continually and persistently you are wrong. But, Arbuthnot, how do you mean to go?”

“I don’t know. In a mail steamer, I suppose.”

“If you can run to it, a yacht would be much better.”

“That’s a good idea, for one could get out of the beaten tracks and see the places that are never, or seldom, visited. I will make some inquiries. And now, to celebrate the occasion, let us all have another glass of port and drink a toast.”

They hesitated and were lost, Bastin murmuring something about doing without his stout next day as a penance. Then they both asked what was the toast, each of them, after thought, suggesting that it should be the utter confusion of the other.

I shook my head, whereon as a result of further cogitation, Bastin submitted that the Unknown would be suitable. Bickley said that he thought this a foolish idea as everything worth knowing was already known, and what was the good of drinking to the rest? A toast to the Truth would be better.

A notion came to me.

“Let us combine them,” I said, “and drink to the Unknown Truth.”

So we did, though Bastin grumbled that the performance made him feel like Pilate.

“We are all Pilates in our way,” I replied with a sigh.

“That is what I think every time I diagnose a case,” exclaimed Bickley.

As for me I laughed and for some unknown reason felt happier than I had done for months. Oh! if only the writer of that tourist tale of the South Sea Islands could have guessed what fruit his light-thrown seed would yield to us and to the world!

NOTE: When Bastin says “I know you are angry because they smashed up the statues of Venus and so forth, but had I been in their place I should have done the same,” is it foreshadowing? You’d better believe it is. Also, a locum tenens is a person who temporarily fulfills the duties of another.

NEXT WEEK: “‘Will anything remarkable happen on our voyage to the South Seas?’ I inquired casually. The planchette hesitated a while then wrote rapidly and stopped. Jacobsen took up the paper and began to read the answer aloud —’To A, B the D, and B the C, the most remarkable things will happen that have happened to men living in the world.'”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: You are reading H. Rider Haggard’s When The World Shook. Also read our serialization of: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail and “As Easy As A.B.C.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.