Idle Idol: Henry Miller

By:

February 8, 2012

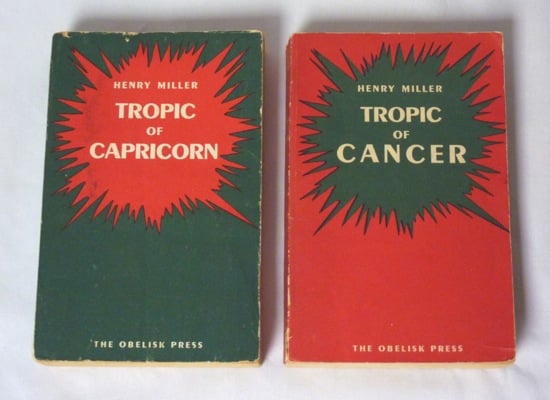

It is some 50 years since “Tropic of Cancer” was published in the United States by Grove Press. First published in Paris in 1934 by Obelisk, a soft-porn imprint, it had been banned as obscene in America until a landmark legal victory overturned the ban, allowing Grove to print it legally in 1961.

— from a Jeanette Winterson essay in a recent issue of The New York Times Sunday Book Review.

This essay was originally published by the British magazine The Idler (issue no. 19), in 1997.

Henry Valentine Miller, born in 1891, grew up in a rough part of Brooklyn, New York. Years later, he would explain his writing style, and his life, like so:

To be born in the street means to wander all your life, to be free. It means accident and incident, drama, movement. It means above all dream. A harmony of irrelevant facts which gives to your wandering a metaphysical certitude… What is not in the open street is false, derived, that is to say, literature.

Accident and incident, drama, dream, metaphysics, and a deep mistrust of respectability (both in life and literature) pretty well sum up the Henry Miller story.

As a young man Miller did in fact aspire to becoming a renowned man of letters, but he just couldn’t travel the accepted path towards his goal. Having dropped out of college after only two months, Miller spent years drifting from shit job to shit job, still toying with the idea of trying his hand at writing. By 1920, however, the 29-year-old Miller was a husband and father, and seemed firmly entrenched as the employment manager of Western Union Telegraph’s messenger department. The years that he spent married to Beatrice (‘Maude’ in his books) and working for Western Union (‘The Cosmodemonic Telegraph Company’ and ‘the Cosmodemonic Cocksucking Corporation’ in his books) were ones of enormous frustration for Miller, who never had a quiet moment to himself even to begin to put pen to paper. Describing a typical day at his job — which was the ‘new media’ of its time — Miller later wrote,

The telephones were ringing as usual. It seemed more than ever senseless to be passing my life away in the attempt to fill up a permanent leak. The officials of the cosmodemonic telegraph world had lost faith in me and I had lost faith in the whole fantastic world which they were uniting with wires, cables, pulleys, buzzers and Christ only knows what. The only interest I displayed was in the pay check.

But as immoral as the idea of chucking job and family in order to develop one’s creative potential seems today, in the nearly part of the last century, particularly in Puritan America, it would have seemed much worse. Miller remained paralysed with frustration, devoting his spare time to cheating on his wife and fantasising about killing his boss. “I don’t want another job; I want a complete break,” he tells his lover in one account of that period. “I hardly know myself, living the way I do. I’m engulfed… I think that if I had two or three quiet days of just sheer thinking I’d upset everything. Fundamentally everything is cock-eyed. It’s that way because we don’t dare let ourselves think. I ought to go to the office one day and blow out (my boss’s) brains. That’s the first step.” Then one night in 1923, Miller met the beautiful and mysterious June Smith (‘Mara’ and ‘Mona’ in his books) in a Broadway dance palace. “I was approaching my thirty-third year, the age of Christ crucified,” he writes of this period. “A wholly new life lay before me, had I the courage to risk all.” Inspired by June’s belief in his ability as a writer, he soon quit Western Union (swearing never to work again), divorced Beatrice and … spent another seven years not writing. The freedom from his family and job he’d so eagerly anticipated was insufficient; his dream of being a distinguished man of letters seemed ever more remote from his real life, which was occupied with wild affairs (with June, who seemed to have many other sugar daddies; with his estranged wife; and — being in many ways a total bastard — with the wives and lovers of his friends), and generally losing himself in dissipation. Not working, clearly, was not in itself sufficient to allow him to write; the utilitarian culture of America itself was repressive enough to dissuade him.

In 1928 however, Henry and June scraped enough money to tour Europe, and everything changed again. In stark contrast with America, where to be broke and homeless was a humiliation, the café culture of Europe, particularly Paris, “where art had some relation to life,” Miller gushed, “where you could sit quietly in public watching the passing show and thinking your own thoughts,” was enchanting. In 1930, having broken up with June, Miller returned to Paris alone, knowing no one, with nothing in his raincoat pockets but ten dollars, a toothbrush, a razor, a notebook and a pen. Almost forty years old, Miller was in an almost angelic state of detachment, ecstasy, and creativity. Absorbent as a sponge, he wandered the streets of Paris with prostitutes and beggars by night, mooched, spending money from new friends and strangers (he developed a sort of Zen of Mooching, as he describes in Sexus: “If you can give yourself up (to borrowing), as with Yoga exercises, that is to say, wholeheartedly, without squeamishness or reservations of any kind, you can live your whole life without earning an honest penny… To be a borrower may be uncomfortable, but it is also exhilarating, instructive, lifelike”), and spent his days in cafes writing his first novel, Tropic of Cancer.

“I have no money, no resources, no hopes. I am the happiest man alive,” reads page one of Cancer, which was published in 1934 (heavily subsidised by Miller’s friend and supporter Anais Nin).

A year, six months ago, I thought that I was an artist. I no longer think about it, I am. Everything that was literature has fallen from me. There are no more books to be written, thank God. This then? This is not a book. This is libel, slander, and defamation of character. This is not a book, in the ordinary sense of the word. No, this is a prolonged insult, a gob of spit in the face of Art, a kick in the pants to God, Man, Destiny, Time, Love, Beauty… what you will. I am going to sing for you, a little off key perhaps, but I will sing.

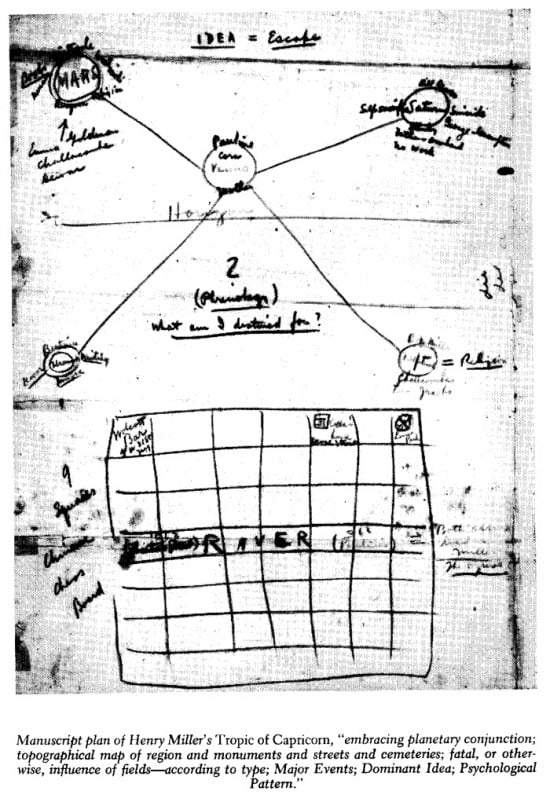

The book, whose anti hero (Miller himself) careens from place to place, borrowing money, getting laid as often as possible, and ranting about joy, writing, and enlightenment, was immediately famous — and immediately banned in all English-speaking countries. So were many of his following books, including Black Spring (1936), Tropic of Capricorn (1939), The World of Sex (1940), and Sexus (1949). Miller was a writer at last. But what kind of writer was he?

The crab, (‘cancer’ in astrology) is, some feel, representative of Miller’s unrepressed writing style, being the only creature which moves sideways and backwards, as well as forwards. But the book’s title has a more prophetic import as well: “Do you know why I called my first book Tropic of Cancer?” he wrote to his friend, the photographer Brassai, “it was because to me cancer symbolises the disease of civilisation, the endpoint of the wrong path, the necessity to change course radically, to start completely over from scratch.” Somewhere between novel and diary, essay and poetry, metaphysics and pornography, the appearance of Cancer signalled a new era in literature; more importantly, however, Cancer must be read — along with the scores of books and essays Miller would write over the next 30 years — as an anti-work, a pro-idleness manifesto. “We have become so adjusted that, if tomorrow we were ordered to walk on our hands, we would do so without the slightest protest,” proclaims Cancer, “Provided of course, that the paper came out as usual. And that we touched our pay regularly. Otherwise nothing matters… We have become coolies, white-collar coolies, silenced by a handful of rice each day.” Proving himself anti-work even when being creative, in Cancer Miller also writes, “The artist, I call myself. So be it. A beautiful nap this afternoon that put velvet between my vertebrae. Gestated enough ideas to last me three days.” Indeed, leaving aside the question of whether Miller’s enthusiastic descriptions of sex were erotic or merely obscene (he insisted they were the latter), the ban on Miller’s writing today seems odd, since only a few of his many books have anything to do with sex. In fact, although what Miller is primarily remembered for today is his radically unashamed approach to sex, the truly radical thing about Miller’s writing is his relentless attack on the ‘cancer’ of American-style utilitarianism, the myth of industrial ‘progress,’ and the Protestant work ethic. The banned Black Spring, after all, contains more passages like this; “The plague of modern progress: colonisation, trade, free bibles, war, disease, artificial limbs, factories, slaves, insanity, neuroses, psychoses, cancer, syphilis, tuberculosis, anaemia, strikes, lock-outs, starvation, nullity, vacuity, restlessness, striving, despair, ennui, suicide, bankruptcy, arteriosclerosis, megalomania, schizophrenia, hernia, cocaine, prussic acid, stink bombs, tear gas, mad dogs, auto suggestion, auto-intoxication, psychotherapy, hydrotherapy, electric massages, vacuum cleaners, pemmican, grape nuts, haemorrhoids, gangrene” than it does one’s like this: “I want a world where the vaginas represented by a crude, honest slit… I’m sick of looking at cunts all tickled up, disguised, deformed, idealised.”

In The Air-Conditioned Nightmare (1945), written after a road-trip across America, Miller continues his assault on modernity: “This world which is in the making fills me with dread… It is a world suited for monomaniacs obsessed with the idea of progress — but a false progress, a progress which stinks. It is a world cluttered with useless objects which men and women, in order to be exploited and degraded, are taught to regard as useful. The dreamer whose dreams are non-utilitarian has no place in this world. Whatever does not lend itself to being bought and sold, whether in the realm of things, ideas, principles, dreams, or hopes, is debarred. In this world the poet is anathema, the thinker a fool, the artist an escapist, the man of vision a criminal.” Consciously in retreat from what he saw as a cancerous civilisation, Miller began to call himself ‘the Patagonian,’ that is to say, a primitive man to whom the taboos and fetishes of modern society seem ridiculous: “We need their paper boxes, their buttons, their synthetic furs, their rubber goods, their hosiery, their plastic this and that. We need the banker, his genius for taking our money and making himself rich. The insurance man, his policies, and his talk of security, of dividends — we need him too. Do we? I don’t see that we need any of these vultures.”

Even the highly controversial Sexus, Miller’s most sex-charged book, is as much (if not more) about his distaste for the modern world than the adventures of his penis. Describing one illicit weekend with ‘Mara’ at the beach, Miller poeticises:

we stretched ourselves out in a hollow of a suppurating sand dune next to a bed of waving stinkweed on the lee side of a macadamised road over which the emissaries of progress and enlightenment were rolling along with that familiar and soothing clatter which accompanies the smooth locomotion of spitting and farting contraptions of tin woven together by steel knitting needles… We weren’t talking, we were simply parking our sexual implements in the free-parking void of anthropoid chewing-gum machines on the edge of a gasoline oasis.

Plexus (1953), the sequel to Sexus, complains that “we know not how to escape the tyranny of the convenient monsters we have created. We delude ourselves into believing that, by means of them, we shall one day enjoy leisure and bliss, but all we accomplish, to be truthful, is to create more work for ourselves, more distress, more enmity, more sickness, more death.” Remember, this was 1953!

Miller was self-consciously speaking in a prophetic voice against progress and Utilitarianism, but his feelings towards work continued to be entirely personal. In Sexus he writes, ferociously,

There was another thing I heartily disbelieved in — work. Work, it seemed to me even at the threshold of life, is an activity reserved for the dullard. It is the very opposite of creation, which is play… The part of me which was given up to work, which enabled my wife and child to live in the manner which they unthinkingly demanded, this part of me which kept the wheel turning – a completely fatuous, ego-centric notion! – was the least part of me. I gave nothing to the world in fulfilling the function of breadwinner; the world exacted its tribute of me, that was all.

Miller wasn’t just for better working conditions, mind you, but for the abolishment of work, period. In Nightmare he writes

In Europe, Asia, Africa the toiling masses of humanity look with watery eyes towards this Paradise (America) where the worker rides to work in his own car… They don’t realise that when the American worker steps out of his shining tin chariot he delivers himself body and soul to the most stultifying labour a man can perform. They have no idea that it is possible, even when one works under the best possible conditions, to forfeit all rights as a human being. They don’t know that the best possible conditions (in American lingo) mean the biggest profits for the boss, the utmost servitude for the worker.

And in Sexus, again:

Everywhere the grim, monotonous walls loomed up; behind them lived families whose whole life centred about a job. Industrious, patient, ambitious slaves whose one aim was emancipation. In the interim putting up with anything; oblivious of discomfort, immune to ugliness. Heroic little souls whose very obsession to liberate themselves from the thraldom of work served only to magnify the squalor and the misery of their lives.

In 1940, with the outbreak of World War II, Miller returned to the United States to stay. He moved to Big Sur (in Northern California), where he wrote the ‘Rosy Crucifixion’ trilogy Sexus, Plexus and Nexus (1959); an anti work study of Rimbaud entitled The Time of the Assassins (1956); Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymous Bosch (1957); and many, many others. His books grew increasingly mystical and ecstatic, as the title of Stand Still as a Hummingbird (1967) indicates. But despite Miller’s growing recognition in his own country (where, despite being elected a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1957, Tropic of Cancer remained banned until 1961), he remained staunchly anti-respectability. “What I like about (some of the young artists I’ve met in the U.S), he writes in Nightmare, “is that they know enough not to want to do a stroke of honest work. They would rather beg, borrow and steal… They look at their fathers and Grandfathers, all brilliant successes in the world of American flapdoodle. They prefer to be shit-heels, if they have to be. Fine! I salute them. They know what they want.” This was not just sheer perversity. As many people discover when they quit their jobs, being a ‘shit-heel’ may actually mean being awake for the first time. In Sexus, Miller notes that “If you stop still and look at things… the world looks absolutely crazy to you. And it is crazy, by God!… From the time you wake up until the moment you go to bed it’s all a lie, all a sham and a swindle.” Anticipating the Situationists’ critique of the zombie-making ‘Spectacle’, Miller notes that the respectable types, who sneer at ‘shit-heels’ for getting high and wasting time, are doing the same thing:

We (Americans) take to dope, the dope which is worse by far than opium or hashish — I mean the newspapers, the radio, the movies. Real dope gives you the freedom to dream your own dreams; the American kind forces you to swallow the perverted dreams of men whose only ambition is to hold their job regardless of what they are bidden to do.

Miller’s joy wasn’t just the gee-whiz optimism of retarded Americans. It was, in truth, a result of his life-long spiritual quest, which early on had led him to the Buddhist notion of detachment. Miller writes in The Colossus Of Maroussi (1941) that

without joy there is no life, even if you have a dozen cars, six butlers, a castle, a private chapel and a bomb proof vault. Our diseases are our attachments, be they habits, ideologies, ideals, principles, possessions, phobias, gods, cults, religions, what you please. Good wages can be a disease just as much as bad wages. Leisure can be just as great a disease as work.

Like his hero Nietzsche, Miller didn’t simply reject what he called the “monkey world of human values”; he wanted to establish a higher morality. “To live beyond the pale, to work for the pleasure for working,” he writes in Nightmare, “to grow old gracefully while retaining one’s faculties, one’s enthusiasms, one’s self respect, one has to establish other values than those endorsed by the mob.”

These new values are scattered throughout his writing, but are fairly well expressed by the portrait of a ‘delicious rogue’ in his almost Taoist essay ‘The Immorality of Morality’:

[The delicious rogue] does nothing for the world, and very little for himself. He simply enjoys life, taking it as he finds it. Naturally he works as little as possible; naturally he takes no concern for the morrow. Without making a fetish of it, he takes inordinately good care of himself, being moderate in all things and showing discrimination with respect to everything that demands his time or attention. He is a connoisseur of food and wine who is never in danger of becoming a glutton or a drunkard. He loves women and knows how to make them happy.

In a less serene style (though the sense is the same), in Cancer Miller exults, “I don’t give a fuck anymore what’s behind me, or what’s ahead of me. I’m healthy. Incurably healthy. No sorrows, no regrets. No past, no future.”

So how do we proceed? Not necessarily by flinging ourselves rebelliously under the wheels of a repressive society. “Meaningful acts require no stir,” Miller writes in The World Of Sex, “When things are going to rack and ruin the most purposeful act may be to sit still.” Pitying the poet Rimbaud for spending years and years struggling to earn enough money to buy his independence from the demands of civilisation, in Assassins, Miller criticises the way young people (of any generation) seek ‘freedom,’ which is only a negative condition, and suggests instead that we seek ‘emancipation,’ a truly ecstatic spiritual state in which one is simultaneously detached from the constraints of civilisation but also still engaged in daily life. “Strange as it may seem today to say, the aim of life is to live,” writes Miller in his essay ‘Creative Death,’ “and to live means to be aware, joyously, drunkenly, serenely, divinely aware.”

When Henry Miller died in 1980, at the ripe old age of 89, he hadn’t held a steady job for almost 50 years.

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE