Early ’60s Horror (4)

By:

November 23, 2011

[Fourth in a series of posts by David Smay on horror movies of the early 1960s.]

Face, my face: whose are you; for what things are you face? … / Do not animals come to us sometimes as if they were pleading: take my face. Their face is too heavy for them and because of it they hold their tiny little soul too far into life. And we, animals of the soul, confused by everything in us, not yet ready for nothing; we grazing souls: do we not implore the Allotter by night to grant us the not-face which belongs with our darkness… — Rainier Maria Rilke (translated by Priscilla Washburn Shaw)

In 1906 Rilke wrote “Nicht Gesicht” (Not Face), and in 1960 George Franju replied with Eyes Without a Face. Facial mutilation is a French specialty, dating from Hugo’s The Man Who Laughs to Gaston Leroux’s The Phantom of the Opera to Bataille’s Story of the Eye to Franju’s masterpiece and into Thierry Jonquet’s Mygale (the source for Almodovar’s The Skin I Live In). We are reassured by Nietzsche’s dictum that “everything deep loves a mask” as we pull on our Krusty the Klown mask before the office Halloween party. Obviously masks and mutilated faces work as the objective correlative for questions of identity, loss of self, constructed personas, false faces. But the potency in Eyes doesn’t derive from a literalized metaphor. Rather it’s conjured from the dazzling wire-walk along a very thin and familiar border:

Feuillade’s genius was in his affectless, matter-of-fact depictions of the wildest, pulpiest lunacy. Franju inverted the equation, while still juxtaposing the fantastique with the mundane, the impossible with the everyday. Franju was on record that “I’m led to give documentary realism the appearance of fiction.” Or, put another way: “Kafka becomes terrifying from the moment it is documentary. In documentary I work the other way round.” Any way you slice it, Franju was fixated on the seam between actuality and fantasy. — David Kalat, Criterion essay

We are now well acquainted with this seam between actuality and fantasy, but it’s worth examining the widely held classification of Franju as a fantasist. Franju stands apart from the New Wave, aligning himself with the French tradition of filmed fantasy while Godard, Truffaut, Chabrol et al., reworked American gangster motifs. Franju did a biopic on Melies, remade Feuillade’s Judex and adapted Cocteau’s novel Thomas l’imposteur. This suggests a connection with the supernatural that simply isn’t present in Eyes Without a Face. I think it’s important to place Eyes Without A Face properly within a tradition of body horror. It’s a science fiction movie, and the French Frankenstein. (Inevitably, in a French Frankenstein, gowns are by Givenchy.)

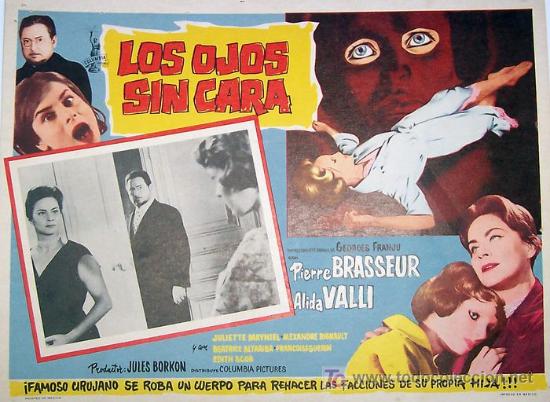

Eyes Without a Face was not well received in France on its release. Franju was one of the co-founders of the Cinématheque Française, and probably the most respected documentary filmmaker in the country. For him to respond to Hammer’s success with an even gorier movie was seen as a cynical cash-in and a betrayal, as if Erroll Morris had decided to direct Saw V. Franju’s most famous documentary, Blood of the Beasts, was set in a slaughterhouse and juxtaposed shots of children playing with the explicit, unflinching, everyday gore of lambs being rendered into chops. He brought that same dispassionate eye to the infamous face transplant scene; a scene so disquieting that seven people fainted when it was shown at the Edinburgh film festival in 1960.

What distinguishes Eyes Without a Face then is this rare, delicately balanced tone: dispassionate yet romantic, gory yet lyrical, fantastic yet mundane. It doesn’t descend from “Turn of the Screw” and its border between the psyche and the supernatural, nor does it dwell in Val Lewton’s shadows. And yet it creates its own genre of Liminal Horror, a distinctly French margin-walking.

Eyes Without a Face became something like the French filmic equivalent of the Velvet Underground; it wasn’t a popular success but influenced every filmmaker who saw it. (And not just Euro-horror directors, though Jean Rollin’s entire filmography depends on it, and Jess Franco remade it twice). Michael Myers’ mask comes directly from Franju, and to note just the immediate knockoffs I’ll list: Atom Age Vampire (1963), Corruption (1968), The Awful Dr. Orloff (1961) and Hiroshi Teshigahara’s The Face of Another (1966).

Thus far we’ve circled around the movie without discussing the plot (from Jean Rendon’s novel, with a screenplay by the Boileau-Narcejac team responsible for Les Diaboliques and Vertigo), which despite its outrageous elements, succeeds narratively, metaphorically, psychologically, cinematically. Dr. Génessier accidentally destroys his daughter, Christiane’s, face in a car accident and works obsessively to repair her beauty. He enlists the help of his former patient, Louise (whose face he had also restored through his genius at plastic surgery) to kidnap young women and cut off their faces to transplant to Christiane. Jacques, Christiane’s fiancé, does not know that she survived the crash, the police are circling in around the disappearing women and the hounds in the basement howl from Dr. Génessier’s cruel experiments. Simple enough to be copied as cheesier exploitation fare, all of which establish Franju’s Eyes as sui generis.

Edith Scob plays Christiane and spends the majority of the movie behind the iconic, uncanny plastic mask. Her performance ranks with Karloff’s in Frankenstein, Lon Chaney in Phantom and Vincent Price’s in The Abominable Dr. Phibes for physicalizing an aching, grotesque poignancy without our being able to see their faces. Even in the few scenes we have of Christiane’s (briefly) restored beauty she maintains a doll-like quality, yet expresses deep human yearning and loss through her dancerly movement. The lyricism in Eyes Without a Face cannot be captured in a still, as it depends so much on Scob in motion, Maurice Jarre’s tender, carnivalesque score and Eugene Shuftan’s cinematography which doesn’t eclipse scenes with Lewton’s soft, enveloping blacks but throws up harder shadows, putting a plastic sheen on wet Macs and illumining trees from below so that they claw eerily at the night sky.

Alida Valli’s performance as Louise is also notable, a rare female Igor, and substitute mother figure. For American viewers who last saw her as the inscrutable object of James Cotton’s desire in The Third Man it’s a bit of shock to recognize her here, thicker, more matronly, with an almost willfully unflattering haircut. Yet she’s still beautiful, and she gives a stock character a tenderness mixed with cruelty, a quality that’s maternal, charming and amoral. Her performance carries a lot of the emotional weight of the film, mediating between Christiane’s vulnerability and the brutal, rational gravitas of Louise Brasseur as Dr. Génessier.

Another element distinguishing Eyes Without a Face from both its imitators and the other movies of this horror cycle, is Christiane’s agency. Despite her fragility and waif-like appearance she alone decides her fate. Though the face-transplant scene is easily the most shocking thing in the film, the most horrifying is that the victims are kept alive. We see Louise lure poor Edna out to the country estate where Dr. Génessier conducts his experiments and she wakes up with her head swathed in bandages, faceless. Edna’s death makes Christiane face (ding!) her moral complicity in this evil. She rejects it, accepts that she has become a ghost in her own life and that it won’t be returned to her. Christiane releases yet another victim, Paulette before her facial flaying, kills Louise and unleashes the dogs on her father.

Since its re-release in 1986, and its restoration and re-release in 2003 Eyes Without a Face has undergone a complete critical reappraisal. It’s an extremely rich and layered text that retains an unusual power. It’s not the face transplant scene that lingers, but the long stretch without dialogue where Christiane wanders through the house in her mask and gown, accompanied only by Jarre’s score — completely severed from her life and yet still present.

I’ve noted the recurrence of themes and images that define this horror cycle, and certainly facial disfigurement and plastic surgery are central interests. Not just in the imitators of Eyes Without a Face but also in classic Twilight Zone episodes like “Eye of the Beholder” and “Number 12 Looks Like You.” The contemporaneous British horror movie Circus of Horror (1960) doubles up with both plastic surgery horror and the carnival themes seen in Night Tide, and Carnival of Souls, and which Jarre’s score echoes. Also Eyes Without a Face opens with an extended scene of Louise driving alone, a recurring motif that Richard Harland Smith notes also in Psycho, The Haunting, Carnival of Souls and Horror Hotel. I’ll explore another common theme of this horror cycle, transmigration of the soul, in my next installment on Roger Vadim’s little seen but similarly Cocteau influenced Blood and Roses (1960).

But before we exit Eyes Without a Face, let me leave you with one more apt quote from Rilke, and the reassuring visual of Edith Scob’s own face beautifully intact in the 21st century.

The woman sat up, frightened, she pulled out of herself, too quickly, too violently, so that her face was left in her two hands. I could see it lying there: its hollow form. It cost me an indescribable effort to stay with those two hands, not to look at what had been torn out of them. I shuddered to see a face from the inside, but I was much more afraid of that bare, flayed head waiting there, faceless. — Rainier Maria Rilke, Notebooks of Malte Laurid Brigge

MORE HORROR ON HILOBROW: Early ’60s Horror, a series by David Smay | Phone Horror, a series by Devin McKinney | Philip Stone’s Hat-Trick | Shocking Blocking: Candyman | Shocking Blocking: A Bucket of Blood | Kenneth Anger | Sax Rohmer | August Derleth | Edgar Ulmer | Vincent Price | Max von Sydow | Lon Chaney Sr. | James Whale | Wes Craven | Roman Polanski | Ed Wood | John Carpenter | George A. Romero | David Cronenberg | Roger Corman | Georges Franju | Shirley Jackson | Jacques Tourneur | Ray Bradbury | Edgar Allan Poe | Algernon Blackwood | H.P. Lovecraft | Clark Ashton Smith | Gaston Leroux |

OTHER HILOBROW SERIES: FITTING SHOES — famous literary footwear | POP ARCANA — spelunking weird culture | SHOCKING BLOCKING — cinematic blocking