Douglas Rushkoff

By:

November 4, 2011

How did we get to where we are now, with Wall Street occupied by a mini-tent city while financial instruments increasingly funnel funds towards the already-wealthy? How did we get to a state where corporations seem to have more legal (and financial) access to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness than the average citizen? How did we get to a point where money is invisible and computerized, yet distributed ever more unevenly?

One thing is certain: we didn’t get here overnight. In his book, Life Inc., author and media ecologist Douglas Rushkoff traces the rise and rise of the corporation, from its beginnings in the late Middle Ages, through its adolescence in the Industrial Revolution, to its present global and virtualized maturity. Life Inc. remains as relevant as when it was first published in 2009, as the public debate over the economy becomes more widespread, and the need for an accurate long view intensifies.

In this #longreads interview, Rushkoff locates the roots of the corporation in the Renaissance, explains how the corporation has made us over into its own image, reveals why there’s a God on the money, and warns what we’re really buying into when we buy that mortgage. But it’s not all talk. In addition to looking back, Rushkoff looks forward to offer some practical — and provocative — ideas on how to unincorporate, and better occupy, our lives.

[The Apple, Star Trek, dir. Joseph Pevney, 1967]

Peggy Nelson: The corporation is not a recent phenomenon; it goes back hundreds of years. What is the origin story of the corporation? Where did it come from, and what is it, exactly?

Douglas Rushkoff: The corporation is the result of two innovations: the creation of centralized currency, and the creation of the chartered monopoly. In the late 1300s the upper classes — the aristocrats, the people who had been feudal lords — were becoming less wealthy relative to real people. As the merchant class and people in towns were producing and doing, the relative wealth of the aristocracy was going down, and this was a problem; the aristocrats wanted to continue the system that had been working for them for the last 500 years wherein they didn’t have to “do” anything to be rich. So they hit upon the idea of passively investing in other people’s industries.

Suppose I am the monarch. I want to make money through your shipping company; how do I get you to let me invest? Well, I use what power I have as a monarch to write up a charter, which means I give you a monopoly in a certain area, and you give me 30% of the shares in the company. The chosen merchant avoids competition and gains protection from bankruptcy, while the king receives loyalty, because the merchants’ monopolies are based on keeping him in power. He doesn’t mind if a few of the merchant class are as rich as he is, as long as he is able to get still richer as a result.

But this was not the promotion of free-market capitalism. It was the promotion of monopoly, non-market capitalism. It was locking into place a set of players and a set of systems that had nothing to do with the free market. And it changed the bias of these merchants away from innovation; in other words, from “how do I innovate and maintain my competitive edge” to “how do I extract wealth from the realm that I now control?”

PN: Then they’ll tend to be conservative because they’ll want to maintain what they have and not risk losing it.

DR: Conservative in that sense, but rapacious in another. Say I’m now in charge of the Colonies. What I want to do is extract their wealth; I want to prevent the people who live in the Colonies from creating any value for themselves. If the colonists are going to grow cotton, that’s fine, but they’re going to use my seeds, my agricultural tools, they’re going to use everything from me. If you are a farmer you’re allowed to grow the cotton but you have to sell it to me at my prices. You’re not allowed to make fabric out of that cotton! Fabricating is creating value. And then you’re going to — what? You’re going to make it into clothes? Those are clothes you could have bought from me! No, no, no, you must give all the cotton to me, I’ll put it on my ship and bring it back to England, then the king’s other chartered monopoly, the clothes manufacturer, will make it into clothes, and then I’ll ship them back and sell them to you — at a profit.

PN: So it’s all export crops?

DR: Right. And anything else I will shoot you for.

PN: And they did!

DR: And they did.

[Monty Python and the Holy Grail, dir. Terry Gilliam and Terry Jones, 1974]

DR: So for about three centuries, the middle and merchant classes were doing really well. Towns that had been in shambles since the fall of the Roman Empire and had lived under strict feudalism were finally coming into their own. This all hinged on the use of local currencies — grain receipts — through which people transacted. They were what we would now call “demurrage” currencies that were earned into existence. Towns ended up creating more value than they knew what to do with. They started investing in their infrastructure and their windmills and their water wheels; and also in their future in the form of cathedrals and other tourist attractions.

PN: They didn’t get money from Rome to fund their cathedrals?

DR: They did not. The Vatican and central Rome did not build the cathedrals. The funds came from local currency, which was very different than money as we use it now. It was based on grain, which lost value over time. The grain would slowly rot or get eaten by rats or cost money to store, so the money needed to be spent as quickly as possible before it became devalued. And when people spend and spend and spend a lot of money, you end up with an economy that grows very quickly.

Now unlike a capitalist economy where money is hoarded, with local currency, money is moving. The same dollar can end up being the salary for three people rather than just one. There was so much money circulating that they had to figure out what to do with it, how to reinvest it. Saving money was not an option, you couldn’t just stick it in the bank and have it grow because it would not grow there, it would shrink. So they paid the workers really well and they shortened the work week to four and in some cases three days per week. And they invested in the future by way of infrastructure — they started to build cathedrals. They couldn’t build them all at once, but they took the long view — with three generations of investment they could build an entire cathedral, and their great-grandchildren could live in a rich town! That’s how the great cathedrals were built, like Chartres. Some historians actually term the late Middle Ages “The Age of Cathedrals.”

They were the best-fed people in the history of Europe; women in England were taller than they are today, and men were taller than they have been at any point in time until the 1970s or 80s (with the recent growth spurt largely the result of hormones in the food supply). Life expectancy of course was still lower; they lacked modern medicine, but people were actually healthier and stronger and better back then, in ways that we don’t admit.

That was right before the corporation and the original chartered monopolies were created, before central currency was created and local currencies were outlawed. When everything gets moved into the center, things began to change.

PN: It seems like the Dark Ages were not perhaps so “dark.”

DR: Yes, I think that’s disinformation. I’m not usually a conspiracy theorist about these things, but I think the reason why we celebrate the Renaissance as a high point of western culture is really a marketing campaign. It was a way for Renaissance monarchs and nation-states, and the industrial age powers that followed, to recast the end of one of the most vibrant human civilizations we’ve had, as a dark, plague-ridden, horrible time.

Historically, the plague arrived after the invention of the chartered corporation, and after central currency was mandated. Central currency became law, and 40 years later you get the plague. People got that poor that quickly. They were no longer allowed to use the land. It shifted from an abundance model to a scarcity model; from an economy based on annual grain production to one based on gold released by the king.

That’s a totally different way of understanding money. Land was no longer a thing the peasants could grow stuff on, land became an investment, land became an asset class for the wealthy. Once it became an asset class they started Partitioning and Enclosure, which meant people weren’t allowed to grow stuff on it, so subsistence farming was no longer a viable lifestyle. If you can’t do subsistence farming you must find a job, so then you go into the city and volunteer to do unskilled labor in a proto-factory for some guy who wants the least-skilled, cheapest labor possible. You move your whole family to where the work is, into the squalor, where conditions are overcrowded and impoverished — the perfect breeding ground for plague and death.

PN: The money that the king was releasing, what was that based on? The other currency was based on grain, it’s a direct relationship to how much grain there is, and as the grain degrades, the currency degrades . . .

DR: The king’s currency? It was actually not even gold: king’s currency was based in the king’s imprimatur. It was coin of the realm because his face was stamped on it.

PN: That’s fairly abstract.

DR: It is. And because people don’t believe in that abstraction, because they’re used to grain receipts being based in something real, precious metal was required for the king’s currency — silver, gold; they had to use something that was considered valuable so people would believe.

Fast-forward to the 1970s. After four or five centuries of people believing it, Nixon realized that people now do believe, so the currency can be taken off the central metal and just be based on belief. That’s when they started putting “In God We Trust” on paper money, when it was taken off the gold standard.

PN: That phrase hadn’t always been on there?

DR: No, it was on coins, but it wasn’t on bills. Because finally, belief is all that’s left.

[Rudolf the Red-Nosed Reindeer, dir. Kizo Nagashima, Larry Roemer, 1974]

PN: How does idea of the individual fit into these other developments?

DR: Corporatism, with its promotion of competition between individuals over scarce resources and money, laid the ground for individualism and for a heightened concept of the self. I’m a media ecologist, I look at media and society as an ecology in which changes in one area reflect changes in another. The notion of the individual was invented, re-invented, in the Renaissance. This is part of why it was a re-naissance, a re-birth of old ideas, the rebirth of Greek ideals. The the Greek notion of the individual, which was always “the individual in relationship to the state,” the citizen, was recast as “the individual.”

The first individual in Renaissance literature was Dr. Faustus, who represented the extreme limits of greed. This was the new man, not a citizen of the city-state but an individual who has his own perspective on the world. We get perspective painting in the Renaissance, which meant the individual was a self-sufficient being whose point of view is important; we get reading in the Renaissance, which meant that a man can sit alone in his study and have his own relationship to the Bible, instead of gathering in the town square or the church, having the Bible read to him by a priest, as part of a congregation. So on the one hand it was this beautiful celebration of individual consciousness and perspective, but on the other it was all in the context of a new economy, one in which individuals were in competition against one another for scarce jobs, scarce resources, scarce land, and scarce money.

PN: OK, I’ll ask: but what about the artists?

DR: Historians say that one of the great things about the Renaissance were the patrons who could patronize a great artist. But before the Renaissance you didn’t need a “patron” in order to be an artist! You could actually live in a town and do some stuff and be a great artist. The Renaissance model of commerce and arts was not a pre-existing condition of the universe. Yes, the Vatican could commission some basilica to be painted, but . . . I’d be interested to see what Leonardo da Vinci or Michelangelo would have been like had they not been part of a centralized bureaucracy, but instead been independent little homespun artist guys. They might have been better artists . . . you never know.

PN: So now we have individuals and corporations as we know them.

DR: The king’s currency, centralized currency, is monopoly currency; demurrage currencies were declared illegal by the king. Why? First, centralized currency is easier to tax. Second, the king could remove gold from the currency whenever he wanted, he could basically suck the value out of it at will. And finally, because this is a currency based in scarcity, everyone has to compete for it. It’s a way to help people who have money be powerful just for having money — not because of what they can spend, but because of what they can hold.

PN: So money becomes a resource.

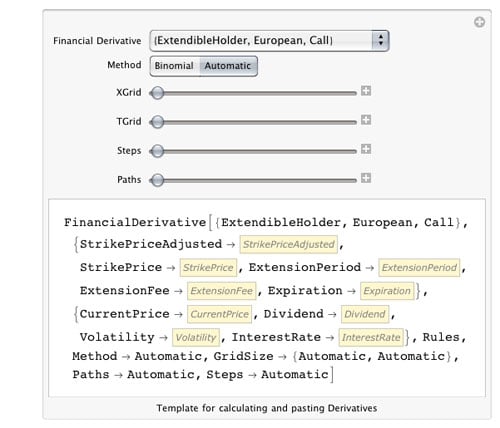

DR: It becomes a resource in itself. Actually it’s a resource once-removed, literally a derivative, the first derivative. Centralizing turns money from a representation of something real into a derivative asset class. We live in this derivatives-based economy today, it has trickled down to us in the form of central banking. Now most people believe that the way to fuel an economy is for a bank to inject money, and the way to start a business is by borrowing from the bank. The way that money comes into existence is it is literally lent into existence. But for every dollar that is lent into existence, for every dollar you earn, there’s a negative on the balance sheet somewhere.

PN: There’s debt right at the beginning?

DR: It is debt, the money we have is debt. Here’s how it works. You start a business by borrowing $100K from the bank. This means that you’re going to have to pay back say, $200K or $300K to the bank in 10 years when your loan is up. Where does the other $200K come from? It comes from someone else who’s borrowed $100K from the bank. And where are they going to get that? Either they go bankrupt, because they can’t pay it back, or they borrow another $200K from the bank. And then that has to be paid back, plus interest. So now they’ve borrowed $300K total and might have $900K to pay back.

The money supply has to grow as a function of interest. The rate at which we do business and make profit is actually driven and determined by the debt structure of the company rather than supply and demand. This is what Adam Smith was actually talking about. Adam Smith was not a free market libertarian, he was not a corporate industrialist the way the Economist or the Wall Street Journal likes to paint him. Smith said that economies only work in scale, they only work locally. He was living in a world where everyone was a farmer, and he hated corporations as much as he hated central government, because he knew that an interest-based economy does not ultimately work. And that is because debt is not actually a product. There’s nothing there. Nothing. Yet that’s what it was made for. The debt-based economy was invented so that people with money could get richer by having money, that’s what it’s for. I’m not saying it’s evil, it was an idea. But, it doesn’t actually work. If the number of people who want to make money by having money gets so big that there are more people existing that way than actually producing anything, eventually the economy will collapse.

PN: It sounds like a big Ponzi scheme.

DR: It is a Ponzi scheme! None of the companies we’re looking at as companies are what they are, they’re all just the names on debt. GM is a name on debt, Sony’s a name on debt.

PN: The New York Times . . .

DR: . . . is a name on debt. They’re all publically-listed, traded companies with these P/E ratios; there are the issued shares, and then there’s the actual business: those two things aren’t the same. The shares are actually more a drag on the system than they are an investment in the company. There’s all this debt to pay back.

[Monopoly Guy, street art by Alec, 2010]

PN: Debt has an emotional component as well, in the sense of, you’re going to owe me, and you’re going to owe me forever. So, better get to work, no slacking.

DR: Slowly over time, as corporations attempted to extract more and more value from people, both as workers and as consumers and ultimately as shareholders and investors in our own 401k plans, we all basically outsourced our lives. I outsource my job to a company. I outsource my consumption to a company, I go to Wal-Mart, I go to Costco. I outsource my investing and savings to companies, I give it to Citibank, instead of the local banker or my credit union or my restaurant or my children or my cathedral. All of our interactions have been mediated by corporations — you don’t work for me and I don’t work for you.

PN: Let’s talk about different kinds of value. Right now we have money, we measure everything by the little green metric. But there are other kinds, we all know that, there are personal relationships, there are other ways of measuring value . . .

DR: We have different ways of experiencing value, but it’s really hard to measure those. I feel that in the current environment, what people could or should be valuing makes them nervous, makes them anxious.

PN: What kind of ways?

DR: Sitting with a friend . . . OK, I’ll sit with a friend as long as I have my Paxil or something, because it’s almost like we’ve been acculturated to be desocialized. I can spend time with you because we’re working, right?

PN: Right, it’s productive.

DR: Productive — and we can measure it on the tape! Is it still turning?

PN: You’re saying money is not value-neutral.

DR: Not only is money not value-neutral, but our money is not money-neutral. Our currency is not the only money. There are other kinds of money, just like there are different kinds of media out there, and they all encourage different behaviors. Computers encourage certain kinds of behavior, television encourages certain kinds of behavior. A gold-based money encourages certain kinds of behavior, a centralized currency encourages certain kinds of behavior, and a demurrage local grain-based currency encourages certain other kinds of behavior. The kind of behavior that our money encourages, intentionally, by design, is: hoarding. This is currency that earns interest over time so you want to hoard it and not spend it. And that’s OK if you need that tool.

PN: But maybe that shouldn’t be the only thing in the toolbox?

DR: It’s like we only have a hammer and it’s really hard to put in screws. Centralized currency is really, really good for competition, it’s really, really good for big companies. Wal-Mart and Citibank can get money more cheaply; the bigger you are, the closer you are to the storehouse. And the big guys don’t want local currencies, they don’t want bottom-up value creation, work-based money, money that is worked into existence instead of borrowed into existence, because that reduces their monopoly over the means of exchange.

PN: The problem with defining ourselves by our jobs or socialism or by economic class is that we’re not just our economics, we’re not just our money.

DR: Right, I create value, but the value I create for my community is not just say, as a baker. It’s not just as a tailor. It’s also as the guy who brings those funny jokes to the party, the guy who has that beautiful daughter . . .

PN: And it’s not just ONE thing and it’s not measurable in just one way.

DR: From the 1920s to the 1970s an iconography was developed that turned corporations into our heroes. Instead of me buying stuff from people I know, I actually trust the Quaker Oat Man more than you. This is the result of public relations campaigns, and the development of public relations as a profession.

PN: Did the rise of PR just happen, or did they have to do that in order to prevent things from getting out of control?

DR: They had to do that in order to prevent things from getting out of control. The significant points in the development of public relations were all at crisis moments. For example, labor movements; it’s not just that labor was revolting but that people were seeing that labor was revolting. There was a need to re-fashion the stories so that people would think that labor activists were bad scary people, so that people would think they should move to the suburbs and insulate themselves from these throngs of laborers, from “the masses.” Or to return to the Quaker Oats example, people used to look at long-distance-shipped factory products with distrust. Here’s a plain brown box, it’s being shipped from far away, why am I supposed to buy this instead of something from a person I’ve known all my life? A mass media is necessary to make you distrust your neighbor and transfer your trust to an abstract entity, the corporation, and believe it will usher in a better tomorrow and all that.

It got the most crafty after WWII when all the soldiers were coming home. FDR was in cahoots with the PR people. Traumatized vets were coming back from WWII, and everyone knew these guys were freaked out and fucked up. We had enough psychology and psychiatry by then to know that these guys were badly off, they knew how to use weapons, and — this was bad! If the vets came back into the same labor movement that they left before WWII, it would have been all over. So the idea was that we should provide houses for these guys, make them feel good, and we get the creation of Levittown and other carefully planned developments designed with psychologists and social scientists. Let’s put these vets in a house, let’s celebrate the nuclear family.

PN: So home becomes a thing, rather than a series of relationships?

DR: The definition of home as people use the word now means “my house,” rather than what it had been previously, which was “where I’m from.'” My home’s New York, what’s your home?

PN: Right, my town.

DR: Where are you from? Not that “structure.” But they had to redefine home, and they used a lot of government money to do it. They created houses in neighborhoods specifically designed to isolate people from one another, and prevent men in particular from congregating and organizing — there are no social halls, no beer halls in these developments. They wanted men to be busy with their front lawns, with three fruit trees in every garden, with home fix-it-up projects; for the women, the kitchen will be in the back where they can see the kids playing in the back yard.

PN: So you don’t see the neighbors going by. No front porch.

DR: Everything’s got to be individual, this was all planned! Any man that has a mortgage to pay is not going to be a revolutionary. With that amount to pay back, he’s got a stake in the system. True, he’s on the short end of the stick of the interest economy, but in 30 years he could own his own home.

[All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace, by Adam Curtis, 2011]

PN: Let’s talk about technology. In terms of administering a shared goods-and-services system, the internet might be a good match. But it also seems that the internet, and machines and technology in general, can stand in place of actual relationships, and can be a stumbling block. How do you negotiate between those ideas?

DR: The word that describes digital for me is discrete. For example, take sounds. With an actual sound, no matter how hard we zoom in, it’s still a real thing. There’s still more fidelity, more information to be found. If I scan or sample it, I’ve now translated that sound in the real world into a number. Something that was an event, in nature, in the world, is now a number. It’s a derivative of reality. That number encapsulates as many metrics and as much information about the sound as I’m capable of including, and I can then make copies of the number and manipulate them. So there’s greater choice in that way. But the only things the number can reproduce about that sound are the things I’ve told it to reproduce.

PN: It only knows what it’s supposed to measure.

DR: The reproduction process also involves a sampling rate, which necessarily leaves stuff out. Even if the sampling rate is so good, so super-mp3, that it’s beyond my conscious hearing, there is still space between the samples. Just like a fluorescent light; there’s space between the flashes.

Now the question is, for all intents and purposes, is it the same, or not? I would argue that for many intents and purposes, it is the same, but for all intents and purposes, it is not. It is a re-creation of a thing, and an approximation, and without even getting spiritual and talking about prana and chi and everything else, there is a difference.

In high school when I needed to do a research project, I would go to the library to find a book. I couldn’t help but see the 20 other books on the shelf nearby, I had to read 20 spines before I found mine. And in reading those 20 spines I would see stuff I wouldn’t have found otherwise, and I might get ideas for my paper randomly — not by predetermined choice. I would see them by virtue of the fact that some librarian who was alive before me made a decision, by virtue of legacies and input and real life messiness. Whereas when I’m in the digital realm and I know the book I want, I type it into Google, and it’s there. And nothing else.

PN: This discrete freedom of choice sounds like a very controlled environment.

DR: Right, what are my range of choices? And who’s giving me that range? People are utterly unaware of that. So when I look at technology I say well great, people have the ability to write online, but they don’t, most of them, have the ability to program. In other words we can enter our text into the little blog box, but we aren’t thinking about the biases built into a daily blog structure, which are towards short, daily thoughts, not introspective . . .

Or look at online communities. I’m going to become friends with another person who owns a 2004 red Mini with a sunroof, like mine, rather than with my neighbor who happens to have a different car; I’m going to look for that perfect affinity. But that’s not a real relationship, that’s my digital relationship, which is discrete! Discrete communities end up groping towards conformity of behavior really quickly.

That’s why it’s a consumer paradise, because it really does celebrate the idea of increasingly granular affinity groups, increasingly granular product choices.

PN: An over-arching theme I found in the book is how the common-sense stuff of our reality, the economy and money and shopping and working, is really science fiction; we don’t live inside a “natural” economic structure — we made it up.

DR: It gets very much like Baudrillard in a way. We lived in a real world where we created value, and understood the value that we created as individuals and groups for one another. Then we systematically disconnected from the real world: from ourselves, from one another, and from the value we create, and reconnected to an artificial landscape of derivative value of working for corporations and false gods and all that. It is in some sense Baudrillard’s three steps of life in the simulacra.

So by now, as Borges would say, we’ve mistaken the map for the territory. We’ve mistaken our jobs for work. We’ve mistaken our bank accounts for savings. We’ve mistaken our 401k investments for our future. We’ve mistaken our property for assets, and our assets for the world. We have these places where we live, then they become property that we own, then they become mortgages that we owe, then they become mortgage-backed loans that our pensions finance, then they become packages of debt, and so on and so on.

We’ve been living in a world where the further up the chain of abstraction you operate, the wealthier you are.

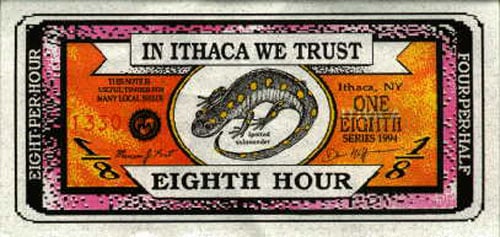

[An Ithaca Hour, an example of an alternative currency]

PN: So since this is a system we created, can we create something else?

DR: Right, that’s what open-source was supposed to be about. I believe that every realm of human experience and design is ultimately open-source if we choose for it to be. That’s why I got interested in religion and money, because those seemed to be the two areas that people would not accept an open-source premise. Religion — of course it isn’t, those are sacred truths! But I would argue that Judaism was actually intended as an open-source religion. I’ve written a book about that, called Nothing Sacred, which was and still is controversial. Because if the Torah is open for interpretation, if it’s this beautiful, myriad, hypertextual, hyperdimensional document that it is, then the whole thing is up for grabs: what happens to the real estate, the Israeli state?

Money of course is the other big area, it’s still the one thing they won’t let you print.

PN: You’ve seen the dual currency idea from the Middle Ages coming back in certain places?

DR: We’ve seen it coming back for 10 or 20 years now in places like Ithaca, New York, and Portland, Oregon; little places with alternative communities and hippies and weirdos and Grateful Dead parking lots and things like that. They could try local currency because people were weird enough to go for it.

More recently, after the economic downturn in Japan, dual currencies started to take hold in the non-“alternative” community. Everyone had time, but no one had money. Everyone was willing to work, but there were no companies they could work for. And since the only way we know how to work is to outsource our employment to a company, things looked bad.

One of the main needs people had was getting health care to their grandparents and great-grandparents who lived in towns far away. No one could afford home health care for them — people to bathe them, walk them around, give them their shots, their IVs, their bedpans. So if you can’t afford the service what can you do? What they did was set up a non-local complementary currency system where you would volunteer a certain number of hours of work to take care of an old person where you lived. You would acquire credits, and then someone who lived near your grandparents would take care of them for the credits you paid. There was no money involved! The currency was literally worked into existence. Even after the economy improved and people got their health insurance back, old people preferred the health care workers who were coming from the real people rather than the ones that came from the companies.

Now it’s starting to hit places in the US where things are especially bad — Detroit, Lansing, Cleveland — these are towns that have resources in people, land, old factories. They have time, they have energy, but they don’t have money and they don’t have any corporate interest. So what can they do? Make a local currency, start doing things for each other. I’ll fix your car, and you do something for me.

Promoting bank-lent businesses is basically saying that you don’t believe in sustainable business models yet. Any business that started with the bank is not a sustainable business model, because it’s already in the debt/interest track. This is where Obama is still confused. He should say, “Look, I realize the economic crisis is real, there are mortgages and loans and we’re going to work on that. But the more important thing right now is, rather than spending $5 trillion of your great-grandchildren’s money on these bankers that screwed up, let’s see how can we spend a teeny bit of money and reeducate communities about real economic development and sustainability.”

And it’s easy! When I talk to economists, or when I talk to bankers, they all say, “well that doesn’t work, you need a bank to go in and invest in a community for it to happen.”

Actually — you don’t. You don’t need the bank.

Life Inc., How Corporatism Conquered the World, and How We Can Take It Back, by Douglas Rushkoff: website.

A version of this interview appeared in Reality Sandwich in July, 2009.

Read more recent Douglas Rushkoff:

Think Occupy Wall St. is a phase? You don’t get it.

Occupy Wall Street beta tests a new way of living.

Are Jobs Obsolete?

Read related essays on HiLobrow:

Rushkoff on HiLobrow.

#longreads on HiLobrow.

Additional resources:

Niall Ferguson, The Ascent of Money

Adam Curtis, watch All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace on the Internet Archive