Linda (18)

By:

October 20, 2011

HILOBROW is proud to present the eighteenth installment of Karinne Keithley Syers’s novella and song cycle Linda, a hollow-earth retirement adventure with illustrations by Rascal Jace Smith. New installments appear every Thursday.

The story so far: Linda is underground. In the last installment she met the team of radiographers that has been tracking her, preparing for her to arrive, as she traveled across the country and sussed out the kind of space she wants to inhabit. As she recounted her surface travels to them, she saw, as if widening out from the single track of her physical path, that an entire industry had surrounded her, pulling fish out of rivers and farms, gutting them and saving the scales, which were then delivered down into the earth, for a use which will be seen.

32.

Inside, there is no weather. This will be its perfection. Its perfection will require its brevity. Imagine, when we drained the marshes, when we built the dams, when we logged the slopes, and when it then rained, hard, for whatever reason, by whoever’s hand, and the cities flooded and the soil gave way and the mud slid, imagine that we did not then have to turn ourselves around and reconstruct the retaining walls, build elaborate gates or levees, but that we just withdrew, abandoned this place, and instead found a place without weather. No hurricanes breaching cities, no tidal waves breaching power plants, no plates to grind against each other. Something below geology, beyond geology, a hollow. Our light will be an artificial light. A light that in and of itself glows, makes light without consuming power, a light that comes from nothing but the intention to light.

When people have imagined the hollow earth, it has always been as a place of more, not less. If an interior sun was imagined it gave light in abundance to a continually replenished and verdant world, a world without winter, nurturing the dream of continuous growth. These utopias anachronized work, made new worlds free of husbandry or tilling, worlds that didn’t require patience, that submitted to no loss.

Even now these hollows have their advocates, adherents to the reports of a certain pilot who flew across the pole and kept going along an indiscernible curve, who passed circumferences of ice to find warm seas and beyond that, lush fields. They claim the boreal glow in their catalog of proofs of warmth, and indeed warmth is key to the vision: an endless summer inside. Those who first envisioned these polar openings, before all satellite imagery or the mapping of the earth, petitioned Congress for expeditionary funds. Latter day believers now post videos that composite photographs of weather circles and strange phenomena, defy the infill of technology and its claims to comprehensive sight, question the official images, propose the possibility of a trans-planetary governmental coverup of a resource rightly our own.

Nested globes suspended serially below us, rotating across each other, were once given to account for the variations of magnetic poles. One man even declared that we all already lived inside a hollow earth, that our nations sat not on the convex but the concave surface of the earth, and that where the liquid core was supposed to go there was instead an interior night sky, another globe spooned by this one, an internally rotating heaven circulating like an angelic Busby Berkeley fantasia, passing our position each night, nodding and blinking to us, not a mystery of expansion but a gift of loveliness, and entertainment almost. He collected his people in Florida, where they settled fairly happily in a commune, but were eventually run off the land by neighbors who could not tolerate the abnormalities of contract this concavity somehow licensed, for the rules of marriage seem not to hold in the hollow earth.

If life was possible inside, inevitably it was a better life. Inevitably the movement away from the surface of the earth allowed us to molt our inequalities, our tedium, or labors. If the end of the world was imagined it was imagined collectively. It required seers and financiers for the preparations, the printing, the land, the vessels.

But I know the hollow is a space of less, not more. Not an eclipse of all but an individual extinction. Not a perpetuity or a solution but a brief and finite room, a clearing that lights up for a while and then stops. And neither it is a utopia. It won’t be shared. It is all for Linda; everyone here works for Linda. She has nothing to do but accept it, receive it, acquiesce to its brevity, and accept its accounting.

33.

Jill leads Linda down the whitewashed tunnels. The walls glow behind the paint. “What is that?” asks Linda, and Jill stops. “Let me show you,” she says, taking a small pick out of her pocket, which she puts to the wall and peels off a patch of paint to reveal a vein below it. Catching the vein slightly, she reaches her finger into it and swabs a sample, which she rubs on her hand. The substance is powdery. Linda reaches her finger into the opening, pulls it out and licks it. “We don’t know how it works,” says Jill. “But you needed light and so there’s light.”

She shows Linda a room, a kind of storeroom. In the middle of the floor is piled a huge stack of fish scales. Around the stack four people are picking out scales individually and separating them by color into different jars. “Everyone, this is Linda,” says Jill. The people look up and take her in. Their eyes on her feel like hands. She manages a hello, beginning to flush from a sensation of their compassion for her. She doesn’t understand why they have it. Jill nods and they all return to work.

Opening a door to a storeroom, she shows Linda a shelf full of vaseline jars. In another room people are seated at long tables putting bristles into fine paintbrushes. They enter a small kitchen, and Jill pours Linda some water. Linda takes out her tincture and squirts it directly into her mouth. She grimaces. “You don’t need to take that, you know,” says Jill. They sit.

“So where are you from?” asks Linda.

“Knoxville,” says Jill. “Not originally, but for the last many years.”

“Where’s your family?” asks Linda.

“Vermont. I moved from Vermont.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know. Warmth? Bungalows?”

“The bungalows are nice,” agrees Linda. She sees in front of her a hovering image of her family home, a Knoxville bungalow, and tries to imagine it calling out to a northerner. In the image she sees her father standing in the front window, lit up at dusk with the blinds still open, while Jill rolls slowly by in her car, sees Jill see her father as a charming installation in a charming town. Maybe Jill lives now in that very house, which was sold a few years ago when she moved her father into a home.

Last night a man who owned a wild animal zoo freed his animals and then killed himself. Some say that the bears and baboons and wildcats were barely roaming, some just standing by their cages as if waiting to go home, when the authorities shot them. This is one of the most popular stories on the Knoxnews.com today. Other stories are local news items mostly: a girl charged with arson after setting her dorm elevator on fire, an insurance executive under investigation for murder, and massive layoffs at the construction site of a new nuclear reactor. The photograph at the head of the story about the escaped animals is of a lion lying dead in a lush field of green Ohio grass. The story explains how everyone was told to stay indoors while the authorities hunted the escaped animals. By the time of its writing, only a wolf and a monkey remained loose. They say the place was a problem for a long time, that the neighbors hated it and its owner, and that this was an act of vengeance.

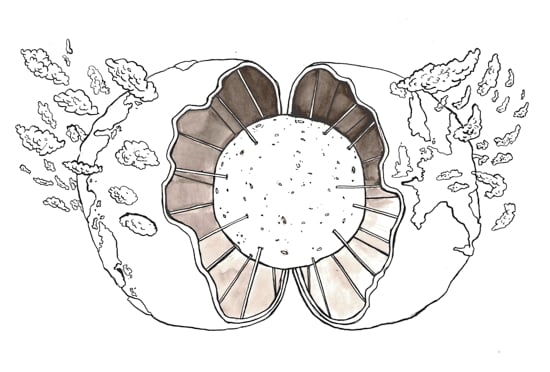

Jill and Linda start to walk again. After a very long tunnel, Jill leads her down a stairwell and opens a heavy door to a loud room where fifty or sixty workers in protective outfits are working a series of thin metal rods drilled out at angles. “We’re under the sea floor,” she shouts. She takes Linda down to the work floor to see one of the rods up close. Inside is a clear cylinder, along which is traveling luminous slime. “Bioluminescent algae,” she shouts.

Beyond the room they take a new tunnel. “I’ll show you the great room,” says Jill, “but it’s very far. Do you feel up for a walk?” Linda nods, and they walk alongside each other. Jill asks Linda about Knoxville, about her life in Nashville, about her father. Her father is like eggshells, says Linda, body and then mind. She tells of his long survival of his wife, of his boredom, of the loss of his clarity, his memory. “When I was young,” says Linda, “my grandmother came to live with us after Grandpa died. But when my mother died my father didn’t want to come to Nashville. He wanted to stay in his house.” But she sold his house. He couldn’t stay there. He wouldn’t let anyone in, not even his grandchildren. Forgot to eat. “I put him in a home. He forgot who I was. Who he was.” All that was left was a kind of wild suspicion. Linda’s father went so slowly. Finally his body followed, as if giving in after a long vengeance.

They walk. “I have a daughter too, in Phoenix,” says Linda.

“I hate Phoenix,” says Jill.

“Me too,” says Linda, “me too.”

They walk. It’s impossible to tell whether they’re going up or down, whether there is an overall curving path to these tunnels. Linda has to sit down and rest. Jill whistles and dog-Linda comes down the hall in front of them. Dog-Linda curls up next to Linda. They nap. Jill sleeps too. All three of them. When Linda awakens Jill and dog-Linda are already up, watching her closely, waiting for her to move. She gets up and they walk on.

Finally they reach the great room. It is a huge underground cavern. Suspended on cables that radiate out to structural points nested into the walls on all sides is a great sphere. There are catwalks and scaffolds surrounding it, and on the scaffolds are hundreds of men and women. Each one has a jar of scales, a jar of vaseline, and a brush. Most are wearing magnifying lenses in front of one eye. They are applying scales one by one to the enormous globe, like the gilders of the Bolshoi, but here, and all for Linda. Scaffolds mount the walls too, in a huge circle around the cavern, and against the walls are more people teasing out luminous veins, slicing them, and spreading their dust across the surface. The whole thing will glow.

Linda turns to Jill.

“Where do I sleep?” she asks. Jill shows her open hands. There is no where to sleep here. There are no apartments. Food? Again Jill’s open hands. There is no kitchen, no dining room. The whole thing will glow. It will go on for a while. Then it will stop.

And now, listen to the next song in the Linda song cycle, Under Bungalows:

Under Bungalows

NEXT WEEK: a return to the kitchen, the globe explained. Stay tuned!

Karinne and HiLobrow thank this project’s Kickstarter backers.

READ our previous serialized novel, James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox.

READ MORE original fiction published by HiLobrow.