Spoiler Alert: Fight Club

By:

October 13, 2011

Caveat lector: may contain spoilers.

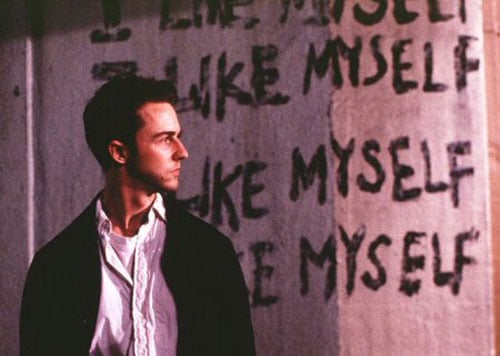

Fight Club, dir. David Fincher, 1999.

So, will you be at the meeting on Tuesday? The first rule of Fight Club is, you don’t talk about Fight Club. The second rule of Fight Club is, you don’t talk about Fight Club. The third rule of Fight Club is . . .

I’m going to talk about Fight Club. Based on the Chuck Palahniuk book by the same name, the film concerns an everyman, a disaffected white-collar worker who can sum up his life with the three C’s: Catalogs, Condo, Condiments. Not surprisingly, for his efforts he’s got insomnia, ennui, and anhedonia.

He starts going to support groups for diseases he does not have, to jump-start his atrophied connection to life. But then he meets a woman doing the same thing; recognizing her as a fellow “tourist,” all his ennui and insomnia come racing back.

Then his house explodes.

Then the movie starts.

Our everyman is always flying. His job requires that he check into auto accidents to conduct cost-benefit analyses of, basically, how much someone’s life was worth. His main perk while flying is imagining the plane crashing and his last moments. In detail. He practices this visualization assiduously.

Then he meets a guy on the plane, a flashy artisanal soap salesman named Tyler Durden, who seems not only engaged with life, but engaged fully. Durden is the idealized id, he does what he wants, when he wants, while wearing wide 1970’s ties. Well, who wouldn’t want that? When our everyman gets home and finds his Condiments in pieces on the pavement, Tyler Durden is the one he calls. Sure, says Durden over a beer, you can crash with me for awhile.

But first you have to hit me. We have to Fight.

So, they Fight. Interested spectators seep out to the bar’s parking lot, and Fight Club is born. Initially a way for alienated and dephysicalized men to get back in touch with reality, it so gains in popularity that Durden sees a further, more systematic, application. Organizing individual Fight Clubs into a larger, decentralized network, Durden morphs the practice into Project Mayhem, whose politically focused culture-jamming has very contemporary relevance, especially in light of the current exposure of our global economy’s shaky foundations and false assumptions.

The premise of Fight Club and its extension is that of an underground, decentralized yet coordinated confederation of the disaffected, their very anonymity a vehicle for effective anarchist action. Pranks that take their politics very seriously.

An idea goes out — pee in the soup at the grand soirees of the rich. An idea goes out — dip vermicelli in an open tube of liquid cement, then break it off in the keyholes of office doors. An idea goes out — gum up the engines of bulldozers by pouring a solution of sugar water into the gas tank. An idea goes out — and then, some ideas become action. But when, and where, and by whom? No. The first rule of Fight Club is . . .

Maybe it reminds you of some other things you’ve seen, or read. Maybe it reminds you of Edward Abbey and monkey-wrenching. Or maybe it reminds you of some things closer to home.

But it’s just a movie, right? Well, a book too. Well, it’s also some fan Fight Clubs started after seeing the film. Which would not be all that different from “real” Fight Clubs. Well, . . .

Well: let’s go online and do some research. In its early days (and occasionally even now), the internet, and then later the world wide web, was touted as exactly this kind of decentralized yet coordinated anonymous network, a forum for the democratic dissemination of ideas, a perfect vehicle for (information about) effective anarchist action.

Yet its early promise seemed cut short when it was sent to military school to learn to behave better — well, ok, it was born a military brat after all — and emerged (to mix more metaphors) as just another bit of urban real estate, another space colonized by advertising, another place where relationship and communication could be forced into an economic straitjacket.

But it has been imperfectly socialized. The pressure to conform split its personality, and the first impish, less controlled persona still peeks out from time to time, not always announcing its presence loudly, but persisting nonetheless. The art-activism of RTMark was one such early presence, a site for the dissemination of anarchist ideas and pranks. Anyone could submit an idea, and then anyone anywhere could invest anonymously, either with money or with action, to carry it out. The only caveat was that the implementation of the idea not injure a person.

Two of RTMark’s more visible projects involved auctioning off votes in the 2000 presidential election; and switching the voice boxes of Barbies and GI Joes on the shelves; so Joe claimed to love shopping, while Barbie wanted to go out and join Fight Club. Kidding! She wanted to go out and actually Fight. More recently, you may be familiar with the media-savvy political performance art of the Yes Men. Hit up the Google for many more examples.

Culture-jamming is often, although not necessarily, political. But the culture-jamming of Fight Club is most definitely political. A hard-nosed socio-economic critique wrapped in a mystery inside a comedy, the implications of Fight Club will stay with you long after you leave the theater. Or get up from the couch. The critique reaches both out, to the financial system and the culture at large, and in, to what you feel, why you act, and who you think you are.

See the film. Read the book. And then go back to your Condo and Condiments.

Or, not . . .

A version of this essay appeared on the Brattle Theater Film Blog, May 2009.

Read moreSpoiler Alerts.