Linda (17)

By:

October 13, 2011

HILOBROW is proud to present the seventeenth installment of Karinne Keithley Syers’s novella and song cycle Linda, a hollow-earth retirement adventure with illustrations by Rascal Jace Smith. New installments appear every Thursday.

The story so far: In part three, Linda traveled across the country in a van, though everyone else in the country was sleeping owing to the darkening and dust caused by a comet crashing into the earth. It was a promised vacation and she deserved it, but in the last installment the globe reclaimed her and she learned that the dust was a dust of decay, an inevitable fragility. But finding her way at last to the coast, and into a radio interview, she renounces this fragilty, rejects it, and leaves the station, walks inland until she finds something like a manhole in the floor of the forest and climbs down into the caverns below the surface of the earth.

PART FOUR

30.

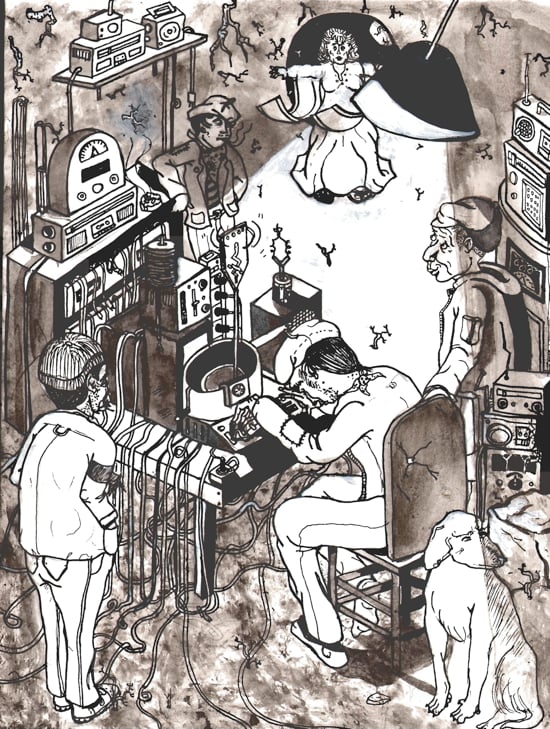

Since the beginning, they have been following her, this group of underground radiographers. They track the incursions and emissions at a border of her thinking, a border so far from her identified center, the place called “Linda,” that she is only dimly aware of her own activity there, and unaware completely of that region’s occupation by these spectral receivers, these transmission genies, who have mapped out along a kind of scaffold an envisioned pathway to the vague edges of Linda, have worked to cultivate and concentrate their perceptive capacity far from any sensory input in the region of their proper bodies.

It is hardest when something insists on its presence. Early on there were troubles with flies, in particular with one untrappable and seemingly indefatigable fly circling the room for hours. And so they had to construct a space underground, a kind of bunker or sealed space, in which to do the work of following Linda. They built shallow bunkers topped by enormous satellite dishes, and after learning to disregard the unavoidable noises of their circulation and their digestion, used the sound of their own breathing to give a rhythmic grounding to their work, a kind of local support for the extended environment.

But when they had finally learned how to do this, when they were finally capable of hovering in the indistinct edges of Linda’s thinking, to see what she needed, they found that she did not know how to imagine this herself. She had spent a life imagining what other people needed and was stalled trying to return this discernment to herself. Her ideas, when she had them, came from magazines or talk shows or second hand reports of other people’s activities, but nothing rang out. They could find in her stream of possible occupations no navigational object that stood in a sincere relation to any sense of need. If she needed something, she was without resource to imagine what it was. It was a sense she had quashed, or maybe never even invited herself to imagine. Still there was a desire, a desire without an object, to go floating, to go free.

And so with little to go on, they tried to figure how to coax her into imagining what she needs, to give herself permission to imagine the space where she wants to be. The team itself is a gift from me to Linda. Some of its members we have met. There is Bessad, and Francoise – she’s the one who came with Bessad up the tunnels before the comet came – and Jill, who planted the metal piece in Linda’s mouth. Others we haven’t met exactly: Kay was playing the part of waitress Linda, and Milton, through a pet schema of mirrors and projectors, appeared as the little man. Kay and Milton also left the fridge in the globe, and appeared from out of the manhole in the guise of ship’s men. They are theatrical, but that can be helpful sometimes. Wallace and Hermann have been thus far mostly busy working on the equipment and disinclined to appear. They were there when the room listened to Linda’s interview on KHLO but absorbed in the finer processes of reception. Not even Linda noticed them slipping in to the back rows of the movie theater, or secreting themselves behind shelves of canisters in projection rooms, and I do not think they made their way up on any other occasion. Of course you know dog-Linda. This is the team, the pit crew of Linda’s retirement. Jerome, the radio man (he introduced himself as Sal but his name is Jerome), is independent of them. His appearance was a surprise and cannot be accounted for except in broadly reassuring concepts, like the incursion of reality, irreducible and unpredictable.

When Linda knelt over a stream by the smoke tree and realized the globe was unwell – when Linda rejected this knowledge – when Linda escaped a whitewashed chamber underground – when the eggshells went missing – when she stole the van – none of these times was Linda properly imagining Linda. She was imagining someone else, someone simpler and more suited to be the heroine of an anecdote that might cause a listener to say, I want to do that! Finding what you need is not without its devastation. Bessad, Francoise, Milton, Kay, Wallace, Jill, Herman, dog-Linda: none of them can generate the basic provision for this finding, which is I think only a sense of direction, a recognition of having passed a small point of inflection where a line has become a curving pathway carrying you across a secret dividing line toward a state of irrevocably else, a state that all this time was there to receive you. It is a region unaccounted for in Darwin, Humboldt, or even Verne. We cannot provide this direction for each other, but we can support this travel, once initiated, can environ it and uninhibit it and guard it from wrong incursions, or do our best to follow its declarations. Linda, destroyer. So they offered the squid, the squid offered the comet, she already knew how to sing and was left only to realize that she knew in particular how to sing to comets.

She preferred not to encounter the it as illness, but as catastrophe, literally something traveling from outer space, something to give meaning and terror and body to the outerness of outer space, not as a definition of farness but as the meaning of irreducible, unpredictable contingency. It travels in waves. It comes when you call it. You submit to its transformations, you skate its surfaces, its dust. For a time you sense a kind of euphoric expansiveness, you feel wide, like the rabbit that become the four corners of the night: peaceful and frictionless. When do you begin to ask after the implications of this ineluctable expansion, Linda?

Never mind. Linda is underground. She has lifted up something like a manhole in the forest floor and has found a ladder leading directly down, and she has found the underground chamber where Bessad and Francoise and Jill and Milton, and Kay and Herman and Wallace and dog-Linda have been waiting, wanting, willing, working for Linda. She is there to tell them what she has seen, so that they can assist, finally, in making the place she where she wants to be, now that her children are grown and her parents have passed and no one needs anything from her and she is free to do anything at all.

31.

There are such things as atmospheric rivers, and there are such things as rivers in the ocean, bands of current and temperature that are identifiable, distinct without strict distinction. Linda is explaining a sense of nearness to things that were beyond the range of her vision, as she toured the continent in the van. Linda is recalling her trip as a moving picture, but a moving picture plus weather, plus atmospheric pressure, and she finds she can read the pressure that plays around her body as she repeats her experience for her listeners, can read it as a now-defined variable in a mathematical expression of what is happening across a wide expanse, that in short as she recalls her own journey she sees not only what was happening, and what she was seeing as she was seeing, but also what was happening further off, what was happening that she was not seeing. In other words her memory of her travels, which she reasonably expects to be a single band tied strictly to the experiences she just had, returns to her in two channels. And when she goes back and tries to repeat a section, it comes to her in three channels, and so on, and so she is telling Bessad and everyone not only what happened but what happened near what happened and what happened near that, continually multiplying until she senses that she might account for a whole continent at once.

But as the proliferation occurs they all notice that the same events are happening everywhere, that this reverie of everything next to everything else is landing again and again on a particular kind of appearance, and that is the appearance of fish, everywhere: squid from the globe traveling in Linda’s wake along the Mississippi eating fish and discarding the skins on the banks of the river, fish farms cultivating rainbow trout, in every minor window a fishbowl with at least a goldfish in it, a store with a small theater tucked off to its side where one can sit and watch exotic fish in a tank accompanied by sweet music, an inland sea drying up and depositing fish carcasses in its recession, a public aquarium in every small town, mountain streams with jumping fish in them, cats behind restaurants plucking fish flesh from fish bones, a mirage that looks like a diamond field from a distance but closer up turns out to be a field of drying fish skins, more fish skins hanging on laundry lines just visible from commuter trains, hardware stores with fishscale-infused paints, childhood rooms with glow-in-the-dark fish still awake and swimming, great white chalk fish on hillsides and supermarkets with only fish fingers for sale, fishing boats out on the sea sending diving bells down to collect luminous undersea fish. And behind all these fish events, a quiet mass of people following in Linda’s wake with buckets, who collect the scales, skinning the fish and throwing the flesh to the quiet mass of bears who follow them in turn. The scales are laid out in piles to season, washed by rain and dried by sun. As she sees it for the first time these piles form a chain, glorious and luminous, like a new mountain chain threading the country, stretching out from the path of the van across all these states. Although she meant to tell of her trip across the continent and what she saw there, what Linda tells Bessad, Francoise, Jill, Kay, Milton, Wallace, Herman, and dog-Linda instead, is that the continent is a plenitude of glittering fish scales and that there exists an entire itinerant industry of their collection, and that the collection has been done and the scales are ready.

And all this is for me, says Linda.

When she is done talking, Herman turns on the radio, and he finds the quiet hum of the quiet army, not even their talking, just the sound of blood moving through them. He places the headphones on Linda’s ears.

Try to get closer, he says.

Linda, guided by hum, moves in her mind’s eye nearer to the people working the stacks of fish scales, nearer to the bears that follow them consuming fish flesh, but as she nears, the individual faces evanesce, and she sees only a kind of afterimage of each one, but upon finer concentration sees that this afterimage is just an image of herself: cleaning, scraping, laying out, smoothing, on each body, the face of Linda. It is a world of all Linda.

On the mountains of scales, each skin as it dries dissipates into separate scales, which sift down into smaller though not insignificant piles. There is enough, she estimates. Enough for a single magnificent room.

Some Lindas can be seen with a kind of boring tool, almost like oversized apple corers, drilling. Where they pass, the ground is pocketed with holes, holes leading to tunnels that thread the crust of the earth, tunnels made by the comet and the moles and the diggers, tunnels that have made the surface of the earth into a kind of lattice, a veined leaf, almost a tent. In their wake, Linda her many iterations get down on their knees and begin to brush and blow the fish scales into this constellation of holes, and sees that the scales are gently luminous. If she could see from above, maybe it would look like a night sky on the surface of the earth. Linda watches as all these Lindas deposit the fish scales, with enormous quietness and purpose, into the waiting receptacles below.

Herman fiddles with the radio and Linda now hears not the circulatory thrum of so many Lindas above, but the sound of falling scales. She allows the sound to make the image clearer, sees the path of these scales move down tunnels, drops, and slides, until they pile in underground chamber that have been hollowed by hand, whose stuff now circulates in the ever-darkening atmosphere of the failed surface. When sound of falling stops, she takes off the headphones.

Jill leaves the room. Dog-Linda licks Linda’s hand. Everyone waits.

Jill returns.

“It’s complete,” she says, “it’s ready.”

And now, listen to the next song in the Linda song cycle, World of All Linda:

WORLD OF ALL LINDA

NEXT WEEK: A history of hollow earths, the master plan for this one. Stay tuned!

Karinne and HiLobrow thank this project’s Kickstarter backers.

READ our previous serialized novel, James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox.

READ MORE original fiction published by HiLobrow.