Enter Highbrowism

By:

September 1, 2011

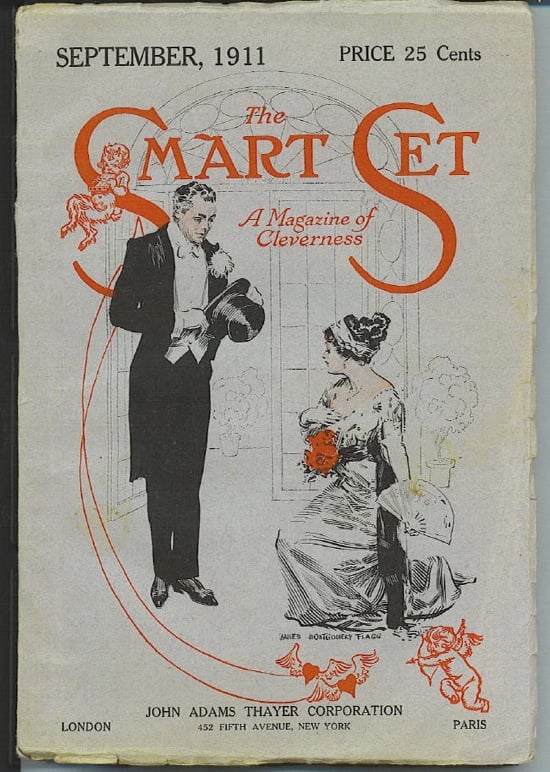

A century ago this month, in the pages of Smart Set, James L. Ford published a fictional account of the origins of a phenomenon he called “highbrowism.” I can’t help but read this as a satirical science fiction story: A mutant species — homo superior, if you will, except actually inferior at everything but striking radical chic poses and getting invited to dinner parties — has made its first appearance!

Other tales about large-domed mutants published in 1911: J.D. Beresford’s The Hampdenshire Wonder, Hugo Gernsback’s Ralph 124C 41+, and William Greene’s “The Savage Strain.”

THE HIGHBROW

By James L. Ford (from Smart Set, September 1911)

HIGHBROWISM is a fungous growth on society often mistaken for real learning or achievement. It owes its existence to the craze for serious matters like municipal politics, the higher intellectual drama and the condition of the working classes that of recent years has diverted the thoughts of a vast number of women from bonnets, bridge, automobiles and Lenten classes.

Whenever the changing conditions of our complex civilization create a need, Nature is always quick to supply it; and so it happened that when women of the “brilliant” brand looked around for someone in trousers with whom they could hold intellectual converse, the pungent fumes of culture filled the air and straightway the highbrow appeared before them like the genii from its bottle.

One of the greatest of modern novelists once wrote a book to show what manner of man an egoist is and wherein he differs from an egotist. Shall it not be permitted then to an humbler scribe to devote a few pages to an exposition of highbrowism, to explain how it differs from true learning and why its prophets should not be confounded with men of genuine thought and accomplishment?

It is eminently fitting, moreover, that I should be the one to write this chronicle, for I was present at the dinner that gave to the town the first of its highbrows and started the craze for toying with artistic and intellectual problems that is still raging like a forest fire in our best society. I was a guest on that fateful night when Kate Smithers, at that time a most charming and ingenuous creature, with deep blue eyes and a small round head like a cocoanut — but now, alas, one of the most brilliant women in society — dealt a knockdown blow over the solar plexus of innocent dinner table merriment by suddenly asking the man on her left what he thought of Kant’s Critique on Pure Reason.

Some day — it will not be soon; somewhere — it will certainly not be in New York — Miss Smithers will put that question to someone who has read that abstruse book, and then the bubble of reputation which has kept her afloat these many summers on a sea of fashionably intellectual glory will collapse, and she will sink beneath the waves of the society which she adorns, to be seen, and listened to, and admired by women, and feared and fled from by sagacious men, no more again forever.

Those who glean their ideas of New York society from a hysterical press, and a school of fiction that is quite as hysterical and even more mendacious, imagine that it is given over entirely to frivolity. But we have only to attend a revel leavened with the uplifting yeast of highbrowism to realize that the Four Hundred, like the undertaker and the coroner, has its serious and even melancholy moments.

It was in one of these moments that Miss Smithers put her awful question to the unsuspecting rodent on her left, causing the fork to fall from his nerveless grasp while a solemn hush descended upon the little company.

Now this young man was a native Bostonian, just beginning to frequent the haunts of metropolitan fashion, and finding it a difficult nut to crack, for his chief equipment was a vapid mind, highly educated; and that, as we all know, bears little fruit save those Dead Sea apples, conceit and stupidity. In his efforts to fit himself with a pose suited to the tastes and idea of the fashionable women with whom he wished to consort, he had essayed many of the lighter conversational topics, only to find himself beaten at the game by others of greater knowledge and nimbler wit. But now the sight of this brilliant company stricken dumb before an empty allusion to German metaphysics told him that his opportunity had come, and he quickly recovered himself and made answer that, although he did not regard Kant’s work as quite sound in its philosophy, he was quite sure that Matthew Arnold was in reality the Pagan Greek that he seemed to be.

By this time the rest of us had begun to suspect that something of an intellectual nature was happening, and I, realizing with quick perspicacity that the time was ripe for action, threw myself into the breach, crying: “Do you think that Bernard Shaw is really sincere?”

This was in the very early days of the Shaw craze, and I honestly believe that I originated the query about his sincerity that has since become so hackneyed that it is known as the “idiot’s gambit.” But it never fails to make a brave showing when sprung upon highbrow circles where it takes equal rank with Ibsen as “a slice of human life” — an ever green observation that may well be termed the “arbor vita of literary discourse.”

Our little dinner table talk passed so quickly that we scarcely understood what was happening; nor did we comprehend the importance of the utterances that I have quoted or dream of their far reaching consequences. I noticed, however, that Miss Smithers’s sweetly simple face took on a new life as the conversation soared toward the ceiling, and that there came into the depths of her great trusting blue eyes a suggestion of intellectual rhapsody which puzzled me, until the party broke up and, the night being warm and still and the sky serene and starry, she dismissed her carriage and asked me to walk home with her.

“Didn’t you notice,” she exclaimed the instant we left the house, “how refreshing it was when I gave the talk a serious turn tonight? I did it purposely, and I assure you that I was nob only surprised but delighted, too, to notice how readily you fell into the spirit of the thing. Your remark about Bernard Shaw fairly made the conversation sparkle.”

I pricked up my ears at Miss Smithers’s words, for I had a strong liking for this frank, warm-hearted, ingenuous woman, whose manner of looking out through wide open eyes of deepest blue upon this great, hard, cold, round world of ours had often proved a source of mild amusement to me. Moreover, she had more than once invited me to dinner, and was always an intent and flattering listener when I touched upon the frothy, bubbling, gossiping, unstable world of theater, newspaper office and studio that is so attractive to those who either know it not at all or else know it very well. Besides, at this period of my life what I thought was a Heine-like cynicism still held its sway over me, and I rather prided myself on saying that a pretty woman was none the worse for being a bit of a fool. Years afterward I learned — with feelings of mortification and rage that may be easily imagined — that, while I was pluming myself on my cheap smartness, Miss Smithers, the target of my bright, cynical wit, was going about declaring that I was an “interesting man” — the term was not as opprobrious then as she herself has since helped to make it — and wondering why I was not asked out more in the best society.

“Ever since I first began to go out,” continued Miss Smithers, after waiting to allow the full significance of her remark to sink into my brain, ” I have felt that society was unsatisfying. When I returned home from even the most brilliant dinner or reception it was with a sense of time wasted, an evening misspent and sometimes a perceptibly loosened moral or intellectual fiber. Nearly every woman friend that I had shared my belief that we of the supposedly fortunate and unquestionably fashionable world were not getting the enjoyment out of life that we deserved. The little uplift in our talk tonight has made a deep impression on me. Good night. I hope to see more of you now, and I mean to give a dinner very soon and invite you and that brilliant man from Boston.”

As I was slowly making my way homeward with mind aflame at the brilliant social prospects that were unfolding before me, I overtook the young man who had “called the turn” on Matthew Arnold with so much brightness and originality. He was walking just ahead of me, his hands clasped behind him and his head bent down after the manner of one in profound thought.

“Culture!” I heard him murmur. “That’s mother’s milk to us Bostonlans!”

“What’s that about culture?” I demanded, as I came up behind him.

“Culture,” he replied, still speaking as if to himself, and not even looking around to see who had addressed him, though it is quite likely that he recognized my voice — “culture is the lifeboat in which the poor earthworm may safely float among the brass pots of plutocracy on the troubled waters of metropolitan society. I am going to launch myself in it without delay.”

And so it came to pass that that historic dinner not only gave an impetus to what passes for serious thought but also quickened into life the seeds of ambition in this young man’s breast and transformed him into a highbrow, the first of the long line of solemn, queer-looking bipeds that have been harassing the town ever since.

It may be that I have dwelt at unnecessary length on the insignificant happening from which highbrowism sprang. Some of my readers may think that I have said too much about Miss Smithers — in my opinion too much cannot be said about that naive, sympathetic and adorable woman — and laid undue emphasis on the sparkling conversation that turned her thoughts in a serious direction; but when we consider the magnitude of the subject, the extraordinary spread of highbrowism to all parts of the country and the race of respected highbrows developed by it, I feel that no incident connected with the inception of this important movement is too trivial to be neglected. Indeed, I make no doubt that future historians will deal with the rise of highbrowism far more exhaustively than I have, and that the house in which Kant’s Critique was first sprung upon the awestruck company, and even the very dining room which echoed to my Bernard Shaw cry, will be carefully preserved by the historical society as a shrine for future generations of the serious-minded.

I have said that the original highbrow was queer-looking. He has long since disappeared from the scenes that he once adorned, but I distinctly remember his domelike forehead, wide flapping ears and fishy eyes — a facial combination seldom seen. So remarkable were his physical characteristics, and so closely were they identified with his fame as a man of intellect, that the belief soon came to be accepted that the one could not exist without the other, and from that day to this New York has never accorded full recognition to any highbrow of ordinary aspect.

Another invariable earmark of the highbrow is his paucity of real achievement. Men both great and wise lived and died before he was ever thought of, but it was not for them that the term “highbrow” was coined. The real Simon pure specimen does not invent a telephone or build a bridge across the East River or direct great enterprises or write good plays or good books or compose music. If he were really to accomplish anything of practical value he would cease to be a prophet. Moreover, his attitude must be invariably one contemptuous of success. His school of thought is one that sneers at all recognized achievement and glorifies the undeserving. Therefore, no matter what form of learning the highbrow may affect or what theories he may advance concerning literature, art, the drama, Socialism, politics or any of the other matters of which he loves to discourse, we may be quite sure that we are not listening to one speaking with authority. I really do not know what measure of contempt and reproach the followers of Kate Smithers would mete out to a highbrow known to have written a single witty line, to have correctly drawn the human hand, to have led a political party, benefited the poor or been able to recognize at first sight any form of artistic real merit.

There is one art, however, in which the highbrow excels, and that is getting into society. Eating, talking and listening to the utterances that fall from sweet feminine lips are all subsidiary to that. He will get into society even if he is obliged to shed human blood in the scramble.

True to her promise, Miss Smithers gave a serious dinner to which both the highbrow and myself were invited, and at which scant attention was paid to my bright and witty conversation, so intense was the interest in the native Bostonian. Much as I disliked him, candor compels me to say that in the art of uttering platitudes in a most serious and convincing manner, he revealed on this occasion talents of the very highest order. I cannot remember all that he said, but I know that his words made a profound impression on everyone present. He said that the pool rooms were a great evil, and that cigarette smoking was bad for very young boys; and his enunciation of these novel theories brought forth a murmur of “How very interesting!”

In the conversazione that ensued after we had left the dining room, I sat in a corner unobserved while the highbrow talked. And although I left early, in great bitterness of spirit, I heard him receive no less than three invitations from women who saw in him a strong attraction for their dinner tables.

Within a month the highbrow was addressing meetings of every sort and description and rapidly acquiring fame. As he always took pains to sit in front of the platform where the newspaper artists could obtain a good view of his profile, his queer-looking face, which anyone could draw, was always included in the “group of notables on the platform” with which many of the accounts were illustrated. It was this circumstance that first revealed to me one of the great advantages in an unusual cast of countenance.

But, after all, the highbrow deserves to be treated as a class rather than as an individual, for the history of the first of the species has been repeated in so many instances that the type has come to be generally recognized, though I firmly believe that I am the first philosopher in the town to study and discuss it in detail.

In the present stage of his development, the highbrow is a distinct social force to be reckoned with. Only the most frivolous company may be called complete that does not boast his presence. In his dull lexicon, boredom and excellence are synonymous terms; although his favorite subjects for lighter discourse are literature, art and the drama, it is unworthy of his pose to commend anything that is really enjoyable or entertaining or funny. He regards reading as a task rather than a pleasure, and tells you what he has read with the pride of a woodchopper reciting his winter’s tale of innumerable cords split and sawed. He affects abstruse philosophy, and is afraid to speak of fiction because it savors of enjoyment rather than culture. And he sneers at all native output save that of Henry James, which the masses can never be expected to understand. He reads Meredith, too — George, not Owen, mind you, for he knows the difference and you can’t fool him — and always from the edition with the author’s name printed large on the outside, the one so popular on shipboard where a quiet daily bluff counts. He reads Shaw, too, but is no more capable of understanding him than the affable English vote seeker in “John Bull’s Other Island” is able to understand the delightful Irish humor that he talks about so genially. He also admires certain modern Irish bards, but knows nothing of Mangan, Davis or Moore. Indeed, it is pleasant to think that those true Irish bards, with their typically Celtic qualities of rhythm and sentiment, of song, rich in tuneful words and with delicate melancholy underlying its humor, have not yet been put to the debasing work of pushing the highbrow societyward.

The highbrow discusses Verlaine, but not Alphonse Daudet, and not one of his kind has ever read “Le Siege de Berlin.” He has long since learned to despise Tennyson, and tradition says that one of his kind once quoted a verse from Longfellow, believing it to have been written by Tolstoy, and, having discovered his mistake, went out and hanged himself, as befitted a Judas caught in treachery to his pose.

I sometimes wonder why he never speaks of the Rollo books, those masterpieces of simple American fiction, as full of purpose and moral as “The Pilgrim’s Progress,” and told so clearly and exhaustively that no question that the inquisitive brain of childhood can frame remains unanswered on their pages! Had Jacob Abbott lived to collaborate with Henry James, the great American novel might not have remained unwritten.

And surely there should be someone to celebrate the sturdy tread of those rugged consonants that march on and on down the pages of the English primer, carrying their simple message of happening or thought in words that had grown gray in the service of honest English speech long before the Norman conquest — words whose meaning not even the humblest intelligence can miss!

“Lo, the ox doth go!” “Now we do go up!” We listen in vain at highbrow gatherings for praise of these models of English prose composition.

But if Rollo and the Primer elude his understanding, fairy legendry has not been so fortunate, for despite its age, beauty, the universal love and respect which it commands and many another quality which ought to render it safe from defiling hands, the highbrow long ago marked it for his prey. Its dried skin has been stripped of all its loveliness, stretched and nailed tight across his door, and marked “Folklore” as a warning to all other living beautiful things not to cross his path. What shall we say of this rape of those ancient tales to which cling so many sweet childish fancies, and of him who deliberately strips them of all the poetry, romance and tenderness of their native fairyland? Is it not enough that we have sat by while he gathered in Ibsen, Browning, Shaw and many another good one that we must needs permit him to pick the bones of “Goody Two Shoes,” “Jack the Giant Killer” and “Hans and Gretchen”?

The Irish peasant tells us that the “good people” who haunt moonlit glen and meadow will hold converse with none but the innocent and pure of heart, and that the only mortals privileged to enter fairyland are children. What would he say to this desecration of an immortal imagery for the purpose of pushing the highbrow into the best society?

The highbrow is perhaps at his best in his attitude toward the theater, his contention being that playgoing is not a pleasure but a scheme for the absorption of culture to be exuded subsequently at afternoon teas. He is quite firm in the belief that the only good plays are those that fail to please the public, or, in other words, that the only good marksmen are the ones who miss the target. Above all, he admires those dramas which, like the shots of the untrained soldier who fires at the moon instead of the enemy, are “above the heads of the people.” His distinguishing earmark, however, is the faculty for missing the true inwardness of everything, including even that which he reluctantly consents to praise.

He lectures in drawing rooms on the Elizabethan drama, and is loud in praise of the heroines of Shakespeare, the philosophy and literary quality of the great dramatist’s work, but he knows nothing of the “stage carpentry,” as he would contemptuously term it, that keeps his plays alive to the present day.

In like manner he misses the genius of Ibsen, much as he may talk about his symbolism. He praises Sudermann largely because he is a foreigner, but sees no difference between the motive that makes “Magda” powerful and impressive, and the miserably sordid amour — “a noble sin” he calls it — of “Es Lebe das Leben.” He has long since discovered that it is safe to praise the German stage, but if he only knew how to laugh as do the wise Germans at their own splendid comedies and farces, he would cease to be the highbrow that he is. A predilection for evil smelling playhouses in the foreign quarters of the town is a factor of no small importance in his pose, and he is to be found wherever a company speaking any language other than our own has pitched its tents. Here, too, he brings his little bands of female admirers, to whom he points out such objects of interest as the elevated railway, the approach to the Brooklyn Bridge and the old milestone near Spring Street, very much as the Reverend Mr. Honeyman used to point out to his flock the various landmarks that dotted the route from his wine shop chapel to the gates ajar.

There is no highbrow living who knows the difference between acting and imitating. I once went to see a Yiddish Shylock, who had been rescued by the efforts of advanced highbrowism from his ill smelling environment on the Bowery and brought uptown for a special matinee, that we might learn what we miss by living above Eighth Street. During the entire play the air resounded with croakings about this player’s “marvelous fidelity to nature,” “repressed emotion,” “impeccable artistry” and “perfect naturalism.” And yet not one of these wiseacres discovered that the Yiddish exotic was not an actor but an imitator, and that his equipment was nothing more than a collection of those mannerisms of speech, face and gesture with which the impersonators of the variety stage have long since made the public familiar.

Curiously enough, the stage highbrow is nearly always of Parisian training and experience. I have never been able to discover why four years spent at the Beaux Arts, in the midst of a people whose capacity for enjoyment is their strongest racial characteristic, should change a possible carpenter into a confirmed highbrow, incapable of doing anything with his hands or brain, and boasting of his inability to enjoy anything in his own land. Reared in the dull fog of London, he is not nearly such a somber, fun hating ass as when trained under sunny Parisian skies, where the drama in its best and wittiest form flourishes as nowhere else in the world.

According to highbrow philosophy, a long course of attendance at the Comédie-Française, so far from teaching us how to appreciate and to enjoy the stage, renders us incapable of recognizing merit of any kind, and compels us to go about forever after shuddering over the crudeness of native American art.

There are other themes of more somber import than art and letters that have come under the spell of highbrow thought. Socialism is one of these. It has given us the teacup or parlor Socialist, a distinct variety of highbrow who utters warning cries about the coming revolution and is fierce in his denunciation of the class which supplies him with champagne and terrapin. He is believed to have exerted a powerful influence over the lower classes, and is a figure of no small importance at the kettledrums of the serious-minded.

His march into society lies over smooth and pleasant routes, for it is of him that women say: “That man is a serious menace to society. We must ask him to dinner.”

ALSO: In October 1900, Ford wrote “The Fad of Imitation Culture” for Munsey’s Magazine. In January 1903, he wrote “Why Shakespeare Languishes” for the same publication.

In 2012–2013, HiLoBooks serialized and republished (in gorgeous paperback editions, with new Introductions) 10 forgotten Radium Age science fiction classics! For more info: HiLoBooks.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin