Reenacting Disaster

By:

May 19, 2011

The story of Ernest Shackleton and The Endurance is one full of so many narrow escapes, near-misses, death-defying feats, and unbelievable events that it threatens to unsuspend disbelief.

Being a true story, this is a problem.

[Trailer for Shackleton, Peggy Nelson, 2011]

Every movie, and almost every book and chronicle, of Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition has left out or de-emphasized significant events in order to construct a believable narrative. In part, this is due to time compression. The several hours of a film, or the several weeks of a book, only have so much room, before the viewer or reader begins to suffer from that plague of the picaresque, novelty fatigue. Once novelty fatigue sets in, the adventure ceases to impress, or to cohere. There are simply “too many notes.”

A number of day-jobs ago, I worked for the director of a museum of natural history, whose hobby it was to collect books on polar exploration. Occasionally I would be asked to track down one of these books, and one day I asked, “What kind of a hobby is that, anyway? What’s so great about polar exploration?” In answer, I received a raised eyebrow.

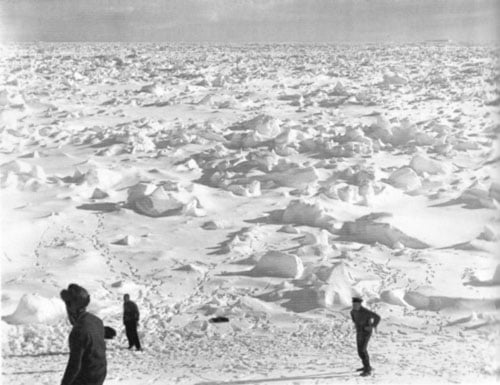

[Pack ice in the Weddell Sea, Frank Hurley]

But several days later, I came in to a book left on my chair. It was Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing (1959), an account of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914-17. I felt obligated to actually read the thing, so I took it home and took it up — and didn’t put it down until I finished. The adventure it told was so incredible, so action-packed, so unbelievable in fact, that I could not stop reading until I made it to the very end.

After that I was hooked. Not on polar exploration itself, or general stories thereof, but on Shackleton’s amazing adventure, his incredible failure and his ultimate triumph.

Since the 1999 exhibit at the AMNH that re-booted Shackleton’s reputation, there has been an outpouring of books, films, and even reenactments of various kinds. So far I’ve found Lansing’s to be the most comprehensive account of the Expedition in any medium. The others, even Shackleton’s own account South, exclude any number of disasters and adjectives in order to keep the narrative in reasonable trim.

Reasonable trim looks very different for Twitter narratives. Telling the story in tweets takes at most few minutes a day, for a number of months. Any fallen disbelief can be restrung in the downtime in-between. And although each tweet is short, they accumulate, and in accumulation can combine to form complex characters — or almost unbelievable adventures.

This project both is and isn’t a straight retelling of Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition.

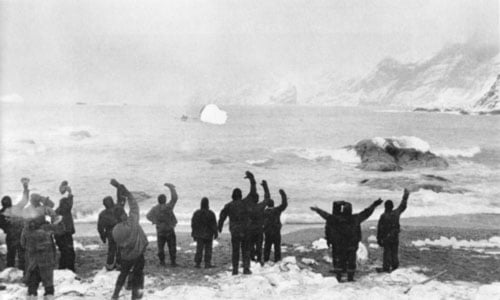

[The James Caird leaves Elephant Island, Frank Hurley; photo later altered by Frank Hurley]

While Shackleton will tweet Shackleton’s entire journey, it will not be only in his words. This is an historical fiction: I will quote him, but more often I will be imagining him, inventing internal dialogue to explore the explorer. I will not be inventing events, but I will be adding additional viewpoints. The narrative will be sampling observations from other explorers of the extremes, such as Werner Herzog and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, and mixing in other contemporary materials and commentary, in an approach similar to my Twitter film In Search of Adele H.

By mapping the negative spaces of extremity, these and other depth explorers have all attempted to limn what it means to be human, by seeing how far we can — or should — go. Shackleton seeks to explore the lengths to which we will go to find meaning, wonder, or the fabled far edges of the earth.

Join the expedition: @EShackleton on Twitter.

Companion website: eshackleton.com.

Peggy Nelson’s other online narratives include the Twitter film In Search of Adele H (2009-2010), the search engine oracle #Scryberspace (2011), and the Twitter reenactment @enoch_soames (2009—).