Denis Kitchen Q&A

By:

March 13, 2011

In the Sixties, some rebels marched, some performed radical theater, a few made bombs. Folks like Denis Kitchen drew and self-published comics — in an effort to claim both art and ideas as property of the artists. Though his publishing house, Kitchen Sink Press, closed in 1999, the list of people published, distributed, and/or represented by Denis and Kitchen Sink, both now and in the past, includes R. Crumb, Charles Burns, Art Spiegleman, Trina Robbins, and other famous names. I spoke with Denis in 2010 about how his childhood love of comics like Al Capp’s Li’l Abner influenced his own underground publishing exploits, and how he and his colleagues changed comics forever.

Peter Bebergal: I imagine comics were the first language you spoke.

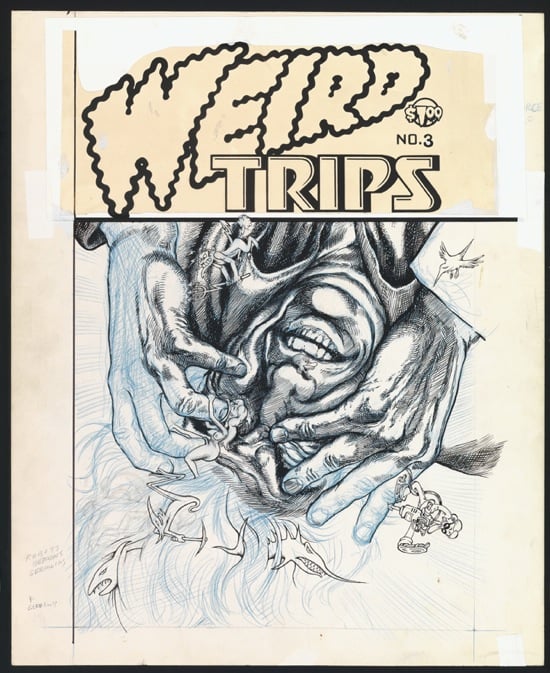

Denis Kitchen: I was born in 1946, and growing up in the Fifties there wasn’t any kind of comics fandom. Comics were strictly kid entertainment and if an adult were caught reading a comic it would’ve been considered an embarrassment. It was the era where Dr. Frederic Wertham was leading a crusade against them so teachers and parents were anti-comics without any real familiarity with them. And let’s face it, some of the comics at that time were pretty twisted and the horror comics in particular were trips in themselves. I still have good memories of being in a closet reading them and thinking, “Whoa, this is weird.” I liked to read and go to movies and I wasn’t living in a vacuum but comics to me were the most satisfying sort of entertainment.

I certainly was also addicted to the Sunday newspaper comics and certain ones left an indelible impression on me too, in particular Al Capp’s Li’l Abner, not only just because he drew the sexiest women in comics but really grotesque looking men.

PB: There was always a hair growing out of a wart.

DK: Yes. He had an amazing imagination and even as a kid I understood some of his satire and political references and then early on I developed a love/hate relationship with Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy. I found when I was swapping with other neighborhood kids it seemed I had more diverse tastes. The other young boys seemed to be focused on the superhero stuff but I liked Little Lulu and Uncle $crooge.

PB: Little Lulu and Uncle $crooge were pretty mainstream. How did you go from those to seeing comics as something subversive?

DK: Actually Little Lulu and Uncle $crooge comics were more subversive than you might think. Lulu was a serious feminist who constantly found ways to infiltrate the boys’ private clubhouse or to outsmart their plans. Growing up I don’t think I saw the gender politics that are obvious now as much as I identified with Lulu in her struggles against power structure, cliques and other oppressive situations disguised as a kid’s comic. John Stanley who wrote and draw many of these was brilliant, though uncredited at the time.

Uncle $crooge was an irascible old coot who lived to hoard and protect his piles of money. He’d dive in deep vaults of coins as if it were a swimming pool. Very surreal stuff. The nephews Huey, Dewey and Louie were the real heroes. What entranced me was the wonderful art and storytelling of Carl Barks, also uncredited. His characters would often end up in exotic locations like the Land Below the Ground or the Seven Cities of Cibola. As an entranced kid, I’d get lost in the psychedelic-like visuals.

PB: How did you ultimately decide that comics would be the vehicle for your growing rebellious spirit?

DK: I don’t know that it was ever a conscious decision. I grew up avidly hooked on the comic books of my era, which were blissfully cheap and plentiful and often quite strange. I showed signs of cartooning talent early on and developed it through school publications and self-publishing into college. When the hippie revolution kicked in, in the late Sixties, I was in my early twenties, going to college and influenced by all those things going on: feminism, the civil rights movement, the earliest gay movement, the legalize pot movement and just the general anti-establishment. It was a crazy time to be a young adult facing the possibility of getting drafted and shipped overseas to a war we all thought made no sense. Then in the midst of all that was the proliferation of drugs of all kinds and experimentation which some delved into more enthusiastically than others. I regard myself as a somewhat, what’s the word, cautious hippie in that I didn’t swallow any pill handed to me.

At that point I expressed myself the best way I could, via comic strips and what quickly became known as underground comix. We lived for the moment but we also knew we were caught up in something large and culturally meaningful. Being a cartoonist was a long-time dream, but my career would have likely taken a much more conventional route if I hadn’t been caught up in the political upheaval and anti-war fervor of my generation and the music, artistic experimentation and the pot and LSD that were part of the times.

PB: Did any of those experiences shape the way you thought about art or thought about what you wanted to do with comics?

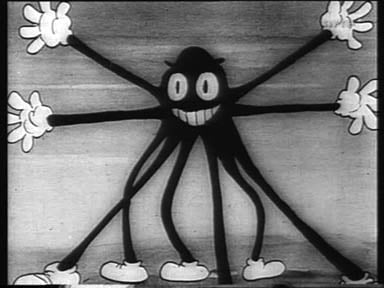

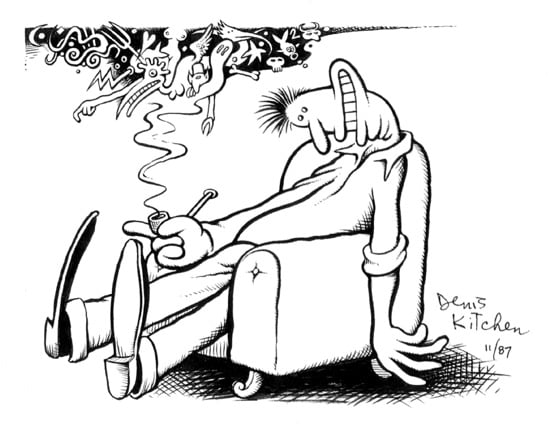

DK: It’s so hard to sum it up because each trip was unique, generally in a good way. My favorite one was vividly hallucinogenic in a way I can only describe as cartoons come to life. I felt like the room I was in was filled with a maze of little freeways and roads surrounding me and little funny animals like elephants and other goofy things that came out of old Fleischer cartoons would be sauntering around. I thinking, “This is the coolest trip I ever took and I want to come back to this place.” But I never did. I feel nostalgic about that trip.

PB: Did acid trips make it into your actual comics?

DK: They certainly did. One of the things that sometimes unnerved the people I was with is that I had a small notebook and a pen in my shirt pocket and periodically I would grab it and write it down. I think my friends thought I was spying on them or writing down their dialogue in a way that was intrusive but I always, “No, I just got a idea and I don’t want to forget it.” The cliché is that you have some great revelation or you solved some wonderful mystery of the universe and then of course you forget it later. I did at least one or two cartoons where I said to myself I have to write this down, it’s the greatest idea ever. Occasionally those would turn into drawings and strips.

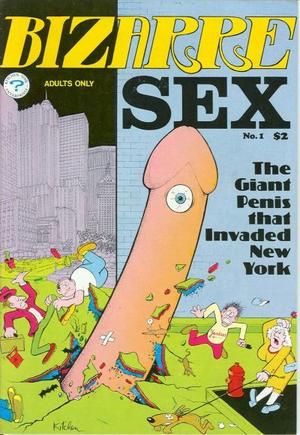

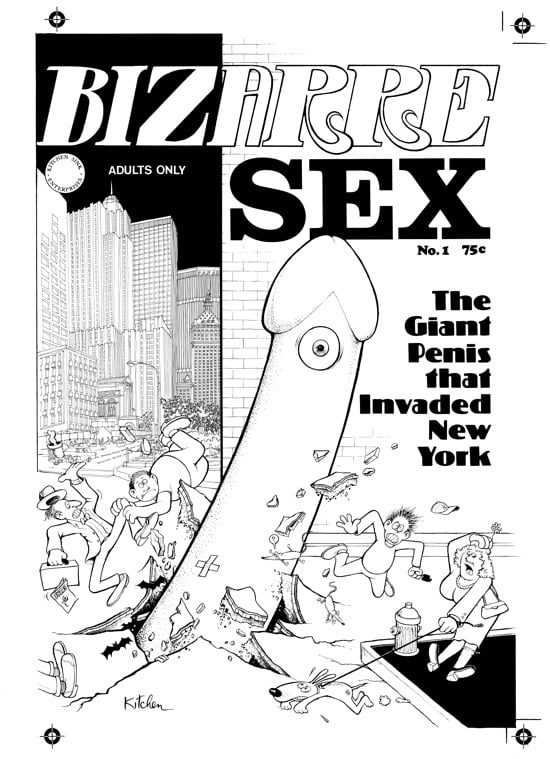

PB: Is that how you came up with the infamous cover of Bizarre Sex #1 that shows a giant penis breaking through the sidewalk attacking the denizens of a city?

DK: That was an acid flashback. It just came to me and I jotted it down. Would it have come to me anyway? [Robert] Crumb famously came up with Mr. Natural and all kinds of things on what he called a very bad acid. God knows what it was.

What perhaps grounded me more than some was taking on the publishing side of comix and overseeing the creation and distribution and financial obligations associated with many other comix artists. You couldn’t do that if marching and tripping 24/7.

PB: It seems that the underground artist had something much more playful going on than the anti-war activists or even those hoping for a spiritual revolution but in some ways is much more deeply subversive. And it must have been even more rebellious doing this in Midwest than in San Francisco.

DK: I chose to stay in the Midwest for a variety of reasons, partly once described as a perverse pride to be able to have this hip subculture and comics and feel like a full blown hippie without having to go to San Francisco because it just became to me a kind of a cliché and I went out there. But I loved San Francisco.

PB: But were you any more impressed with their comics than anywhere else?

DK: There was something unique that first fully flowered in the Bay area and certainly those guys are the obvious pioneers. But in a true sense there was a movement that seemed to be simultaneously bursting forth from everywhere, even in small towns and places where maybe it’s less recorded. But certainly there had to be enough supporters to both put them out and to buy them as there were hundreds of underground comix and newspapers scattered across North America.

PB: It’s like the drug dealer who is also a user. You deal just enough so you can keep doing it.

DK: I think that was it. And I think that’s an important point too because you can’t trade in anything without economics intruding in some way. Speaking for myself and most of the freaks that I knew, there wasn’t a terrible motivation to make money. We just wanted to be able to continue doing what we were doing and have fun. Nobody was looking ahead.

PB: Did you want to change the world with comics?

DK: It sounds so dopey to say that but I think yes. I was already a serious socialist, in fact a card-carrying socialist when I was also becoming a hippie, so I had already certain Marxist thoughts about how people ought to best organize and share the means of production. It’s a little simplistic looking back, but at the time I was a true believer and it melded fairly easy with the hippie stuff. But aside from the politics which I wasn’t in terribly long I shared the almost universal feeling among my freak peers that we could bring peace and love and even end the war.

PB: So how did drawing a giant penis terrorizing a city help this cause? Because, to be honest, that was so much of what underground comix were at the time.

DK: In a word, liberating. I grew up at a time when comics were under the Comics Code authority. The publishers pledged to not include a long list of things in the comics and so I saw the comics get less interesting. My generation of cartoonists was taking glee in breaking all those restrictive rules. My contemporaries and I knew enough about the comics business to know it was a pretty shitty set up economically and structurally. You didn’t own your own work when you worked for Marvel or DC Comics.

PB: But weren’t you secretly reading Silver Surfer comics?

DK: Actually not secretly. When Stan Lee started the Marvel Comics generation around 1961, was really before the hippie movement so I was hooked on Marvel comics in high school and even into college. Those comics predated any experimentation with drugs and lifestyle so some of the hippies who had already been into them would see them, whether it was Silver Surfer or Dr. Strange, in psychedelic terms. Stan Lee was kind of unwittingly one of the heroes of the youth movement even though he was straight as an arrow himself.

PB: Nevertheless working for a company like Marvel or DC was all work for hire.

DK: It was all work for hire. It was tedious. They handed you a script. You did what they told you. It didn’t matter if they printed 100,000 or a million. It didn’t matter if they sold the rights in Germany or Japan, you got the same amount. It was the cartoon equivalent of a factory job, where you were on an assembly line. You did your part, and maybe you got a pat on the back and not much more. It was a dreary prospect. So even those of us who liked Marvel comics and the fewer who liked DC comics, we didn’t see working for them as really a prospect.

PB: That wouldn’t have been making it in an authentic way?

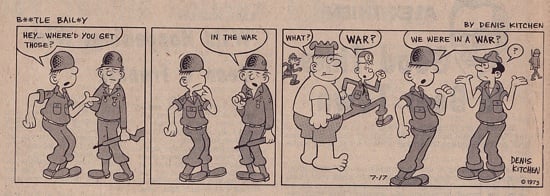

DK: No, not at all. And yet we loved comics. What was the alternative? Well, maybe I’ll do a newspaper strip but then the syndicates were tough. You knew the audience there ranged from kids just learning to read to really old people so it had to be kind of vanilla so to appeal to everyone and obviously a lot topics were verboten. You could get richer there, you could not quite own the strip but you co-owned it with the syndicate so it was somewhat appealing. Middle class was the word we would’ve used. So the only way we could make comics was to make them ourselves and figure out a way to sell them ourselves.

You have to understand I first drew my own comics in a vacuum. I’d heard there was a Zap Comix but it took me forever to find one and so I just figured out a way to print mine locally; as many as I could afford. There was certainly no distributor who would handle it. I literally went around the Eastside of Milwaukee myself which was the college area where most of the hippies resided. I would put them on consignment at records stores and head shops. I kept track of everything and I went back and I would collect the money, give them more. I was methodical about it.

PB: And people bought them?

DK: Yes. Absolutely. They were flying off the shelves and that was when. People would print their own book of poetry and it’d sit there for a year. There was something about comics and the fact that we were tackling social issues and enough of it was either blatantly or subtly part of the culture. The titles and subject matters spoke clearly to a hippie audience. It became self evident that these were alternative readings and word quickly spread that if you read them when you were high it was a trip unto itself. You could get high and you could watch TV or go to a movie, but with rare exceptions they weren’t intended for you to be in an altered state. With the comics you had a sense that the guys who did them might’ve been in an altered state also. And things would be funnier when you were high.

PB: Whether they actually were or not.

DK: It varied from person to person and humor is such an amorphous thing anyway. The cover of Bizarre Sex #1 just struck me as being a funny thing. Either you laugh at it or you don’t get it at all. I don’t think anyone ever thought it was pornographic in the sense that wasn’t anatomically correct. It was clearly a cartoon-y, stylized, phallic creature.

PB: Very different from the way, say, Crumb would’ve drawn it.

DK: Crumb’s would have looked more like a real phallus. You’re touching on something too, that was kind of an unstated rule. If you were a cartoonist and you were going to work for Marvel or DC, they clearly had a house style. What the underground comics encouraged were total idiosyncratic styles, including lettering. Some artists lettered really neat and some in a way that was harder to read but it was a distinctive signature. You could tell one guy did it. At mainstream publishers the comic was passed from a letterer, to a penciller, to an inker, to a writer. In a sense it was the French term the auteur, applied to comics almost better than a film maker because the filmmaking process is virtually impossible to do singlehandedly, unless you’re doing a very small film. Comic books represent the one form of graphic story telling where it really can be a singular vision.

PB: Were you worried that being a publisher you would become the enemy?

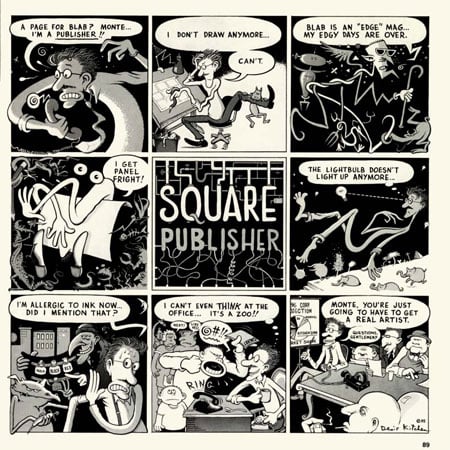

DK: When I found myself kind of by default evolving from primarily a cartoonist to primarily a publisher, I had these idealistic ethical rules that I insisted on applying. Having been a cartoonist I had a bad experience with an outfit called the Print Mint and that just to me made it even more important for me to treat other cartoonists well. I cant even say with 100% certainty they were screwing with me. But they wouldn’t give me even the most basic accounting.

PB: Did they think you were just a dumb stoned hippie?

DK: I think there were a lot of business people who took advantage of the fact that hippies weren’t paying attention to details. But just because I was a hippie, it didn’t mean I was stupid, or didn’t mean I didn’t have any business sense. I found out when I evolved into being a publisher that most artists very much appreciated getting an honest accounting, getting checks regularly, being told how many were printed, and getting told when a comic was being reprinted. All those things that just sound basic and obvious were not standard industry practice. This was an industry, and I use the word industry loosely, we could control.

PB: The true DIY.

DK: Yes, and some serious dollars began to be involved. I remember when a colleague at Rip Off Press told me they’d sold their millionth Freak Brothers. Guys like Gilbert Shelton and Robert Crumb were earning very, very good royalties that would have totally blown away guys working for Marvel or DC at the top roots. Somebody was working for one of the majors and I remember saying, “You should do stuff for the undergrounds sometime.” He said “You kidding? I’m making top dollar over there,” which was in the $100 to $200 range per page. And I cited Crumb’s Homegrown Funnies that had been printed many, many times and I said, “I think to date, Crumb has made about $800 per page.”

We weren’t out to convert people who worked for the big companies but you would rub shoulders with them at conventions. And inevitably you compared things and some of those guys who were really straight. Everybody makes their accommodations. Everybody makes their compromises and not everybody lives in a commune and grows a beard.

PB: Did the mainstreaming of the counterculture hurt the creativity of underground comix?

DK: We knew from observation and history that the system or capitalistic forces co-opt everything, and that eventually it would have some effect on underground comix. But I think we were far less affected than things like fashion and music and film where much bigger dollars and audiences were affected. The underground comix stayed pretty weird and out there for quite a while without what I’d consider any outside corruption. It helped that key artists like Robert Crumb were pretty incorruptible. He turned down all kinds of opportunities to do Pepsi billboards and Toyota ads. And, let’s face it, most underground comix were not capable of being brought into mainstream America. I’d argue that the essential creativity of comix only got better deeper into the ‘70s. What affected the comix movement more than anything was the quick decline and disappearance of head shops. Distribution is everything, and periodical distributors wouldn’t touch us.

PB: Are there any risks left for younger comic artists to take?

DK: Always. If you’re talking about comic book artists, the new generation benefits from having censorship and subject barriers knocked down by an earlier generation or two. But every generation has its own hypocrisies and prejudices and inequities to address and addressing them always has inherent risks. The graphic novel genre now permits cartoonists to break out of the relatively narrow head shop market or comic book shop nerd market that restricted my generation, into mainstream outlets which is great on one hand but risky if you have to appeal to those outside a comfortably smaller and receptive audience, while new technologies and formats like iPads and Kindles are opening up a world audience.

Sharp new cartoonists have an amazing opportunity now to aim at a niche audience or to reach out to potentially vast numbers of readers and, in either case, there are risks to be taken creatively. I think we will see more literate comics and less masked, caped super-powered characters as both creators and audiences come to expect increasingly sophisticated combinations of words and pictures. It’s an exciting time to be a young comic artist but still one fraught with creative challenges and risks.

CHECK OUT Joe Alterio’s Cablegate Comix | HiLobrow posts about comics and cartoonists | unpublished Kim Deitch Q&A