De Condimentis (7): Balsamic Lies

By:

January 14, 2011

Seventh in a series of posts revealing the secret history of condiments — and the influence they’ve had upon the course of history.

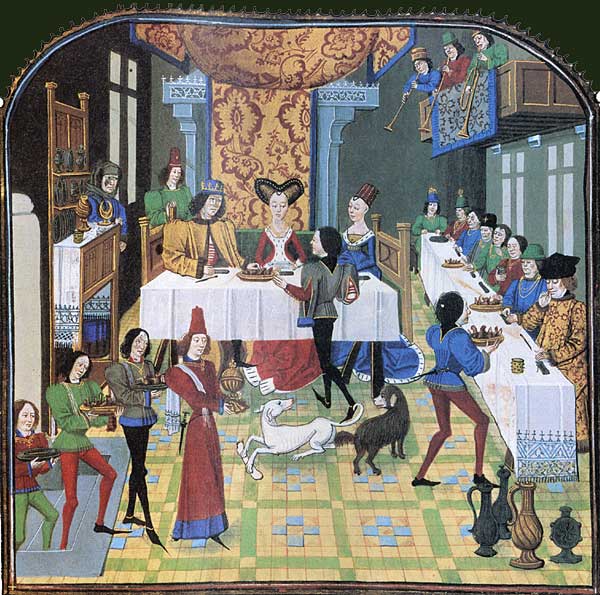

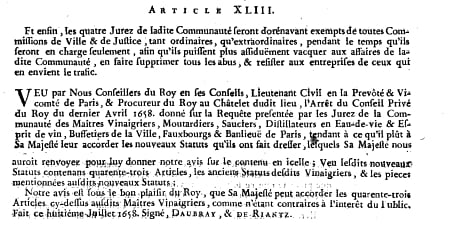

Mustard, ketchup, mayonnaise, worcestershire, hot sauce, barbecue sauce — not to mention relish and pickles — none can be made without vinegar (you can actually make a really insipid mayonnaise without vinegar, but don’t do it). Without vinegar you’d be hard pressed to think of a reason to eat anything, and because it has always been so central to the act of eating, vinegar was turned into a product while most people in Europe were still flinging filth at one another. In 1394, Vinaigriers moutardiers sauciers distillateurs en eau-de-vie et esprit-de-vin buffetiers, the world’s first corporation, was formed in Orléans. Vinegar, Mustard and related products — they also had the verjuice monopoly. Once nearly as popular in cookery as vinegar, verjuice has nearly disappeared from the worlds cupboards, but deserves a mention: Made from crushed, unripe grapes, verjuice combines the acidity of vinegar with the grape-iness of wine — it lacks vinegar’s versatility, but does have the honor of appearing in Dumas’ Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine (1873), though vinegar does not.

It’s not random that all of these were grouped under the umbrella of a vinegar corporation. Mustard sure; eau-de-vie is distilled fruit alcohol, and esprit de vin, distilled wine, both peripheral endeavors that would use the same raw materials and equipment (more or less) as vinegar production. Buffetiers were keepers of wine shops, though later watched over the king’s table (it’s where beefeater comes from). What’s most interesting is that “sauciers” fell under the dominion of vinegar makers as well, though it makes sense from a 1394 point of view. Back then sauces weren’t hollandaise, puttanesca, beurre blanc, marsala or demi-glace; they were a little simpler — simple enough that many would today be called condiments. The 14th-century collection of French manuscripts collectively called The Viandier of Taillevent has the low-down:

Cameline: ginger, cinnamon, cloves, grains of paradise, mace, pepper, vinegar.

White garlic sauce: Garlic, breadcrumbs, verjuice

Fresh herring garlic sauce: fresh garlic, verjuice, herring heads

Robert’s beard: onion (diced, fried in butter), verjuice, vinegar, mustard, pepper (a strong mustard sauce — Rabelais mentions it)

Garlic jance: ginger, garlic, almonds, verjuice

Black pepper sauce: ginger, pepper, burnt toast, verjuice, vinegar

The cooked and uncooked sauces were essentially the same; you just boiled the cooked ones. I’m sure many an Italian traveler, perhaps having heard that Paris was turning into a lovely little city, hurried home to the relative sanity of Rome or Florence after being served fresh herring garlic sauce. The heads, you see, are where all the flavor is.

As vinegar moved from being a product that individuals made in their homes to a product that you purchased at the market, vinegar makers standardized their manufacturing techniques. Mimicking this change, in miniature, the vinaigrier, once the 5-liter jug that most every household used to make their own vinegar, is now the name given to the small bottle of vinegar that goes on the table (with its mate for oil). To create a regular supply and uniform batches, the “mother” system of vinegar production was used (and remains how virtually all vinegar is produced today). Each batch of vinegar is started with a bit of the last batch — the mother; the same idea as a sourdough starter. No more relying on the vagaries of wild bacteria; vinegar was produced in predictable quantities and the quality was uniform from batch to batch. In general terms, this was a vast improvement — wild yeasts and bacteria can produce inferior vinegars and are frequently mucked up with other free floating microorganisms. On the other hand they were vital, different, and undoubtedly produced some exciting vinegars — serendipity was sacrificed to the machine.

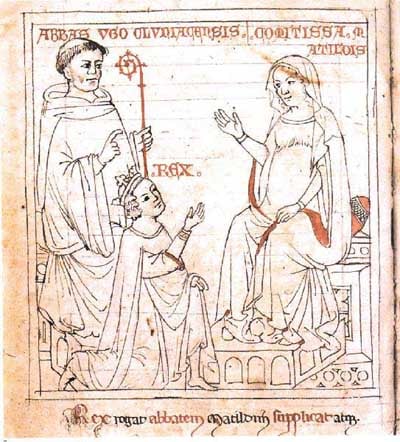

Is there a word for serendipity that turns out to be incredibly unfortunate? In a recipe of surpassing popularity throughout the Imperial period (it appears repeatedly in the fifth century compilation of Roman recipes called Apicius), the Romans boiled grape must (crushed whole grapes) in lead pots to produce a curiously sweet condiment they called defrutum. The “curiously” part was due to a reaction between the weak acetic acids in the grape and the lead in their pots — in addition to cooking the mixture down to grape syrup, they were also producing lead acetate or “sugar of lead”. By the middle ages, alchemists had figured out the reaction and were pouring vinegar directly on lead to produce the powdery, white “sugar” in far greater concentrations. In a world where honey was the only reliable local sweetener (white sugar was available but expensive), sugar of lead was extremely, even homicidally popular. Centuries later the deaths from massive lead consumption are still being sorted out, but Pope Clement II, previously only famous for his decrees against simony and in favor of sweeter pizzelle, appears to have been a victim. Some have even contended that the gradual stupidification of the Roman population is what brought about the fall of the Empire (which is patently ridiculous, since everyone knows it was the fish sauce shortage of 409). Sugar of lead was also used for the better part of two hundred years as a cure for sore nipples and at various times for dysentery, epilepsy, yellow fever, jimmy leg, and poison ivy. Though it was outlawed for food uses around 1800 in most countries, it was still commonly used as a sweetener and to mellow a harsh cider for at least another one hundred years.

All of which brings us, more or less, to the vinegary elephant trying vainly to hide behind that potted palm. That most condimental of all vinegars; balsamic. Virtually unknown outside of Northern Italy a few decades ago, balsamic is now what most people picture when vinegar is mentioned. But it’s a trick, a ruse, a bamboozlement. What you buy in the store isn’t a dumbing down of balsamic, like mayonnaise or ketchup is dumbed down when mass produced, but a falsehood, a culinary cubic zirconia. It’s a reconstruction of a half-remembered condiment — the original was dark, viscous, sweet, acid — reverse-engineered with ordinary wine vinegar, caramel color, sugar, and a little actual balsamic vinegar (if you’re lucky). But it’s not real — no more than caviar cream cheese is caviar, or Hawaiian Punch is fruit juice. They should actually call it balsamic punch.

Actual balsamic is made through a painstaking process that just doesn’t transfer to a large scale — or a reasonable price — and has stayed more or less the same since the middle ages. Grapes are boiled down to concentrate the flavors and sugar, and the resulting thick juice is put in a large wood barrel in an uninsulated attic. Emilia-Romagna, the region of Italy where balsamic is produced, has hot summers and cold winters, just what this slow-fermenting vinegar needs. Years pass, the vinegar a slow bubbling murmur overhead, before it is ready to be transferred to smaller and smaller wooden barrels until, at least twelve years later, it’s done. The heat in the summer causes an interaction between the sugars and the amino acids that produces aroma molecules typically found in roasted meats — a sort of olfactory umami.

In addition to its lengthy processing, balsamic is unique among vinegars in that it produces alcohol and acetic acid more or less simultaneously (if slowly) — there is no “wine” stage for this vinegar; yeasts ferment the sugar to alcohol but the bacteria immediately turn the alcohol to acid. It’s a lovely and impossible thing to make, and that’s why it costs $200 for three ounces. It wasn’t an accident that it went unmarketed for over six hundred years, and the large-scale vinegar production methods bequeathed to us by Vinaigriers-Moutardiers are completely inadequate for dealing with a product that cannot be sped up. You can make bad Scotch by speeding up the process and cutting corners, or cheap wine, but not balsamic. Winding our way through vinegar history, it’s funny, after all the stories, tall tales, and whispered cures fermented over centuries, we end up with a lie. Except it’s true.

MORE CONDIMENTS: Series Introduction | Fish Sauce | Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc. | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.