Goudou Goudou (4)

By:

December 6, 2010

Fourth in a series of posts.

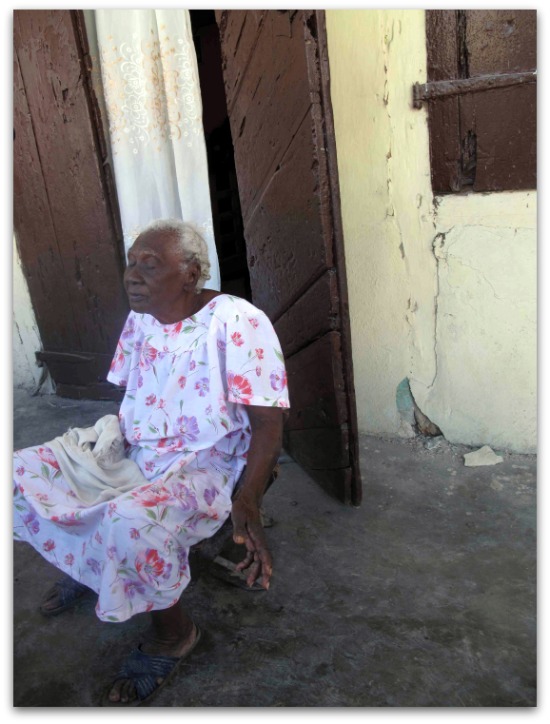

Yayi drags her tiny chair around the yard, pausing to sit here, then there, her tiny head a fuzzy coconut, her arms fluttering as if in an effort to hold up her tough old hands. She swings a leg and waits till she’s sure her foot is planted well before swinging the other. Her body is lost in the billow of a flowered housedress. She is 88 years old. She is beautiful. She is too sad.

Grand-mère Yayi flaps her arms crying “goudou goudou goudou goudou goudou” a song sung by Haitians as they re-enact where they were when the earthquake hit. Her voice is a low rumble, the pelting sound of falling stones. Children have begun to do “goudou goudou” dances, repeating the quake mantra, jittering and jiggering around so effectively that when you watch, you feel the ground roll and roil.

The story of this gran moun is one Roudeline wants to tell.

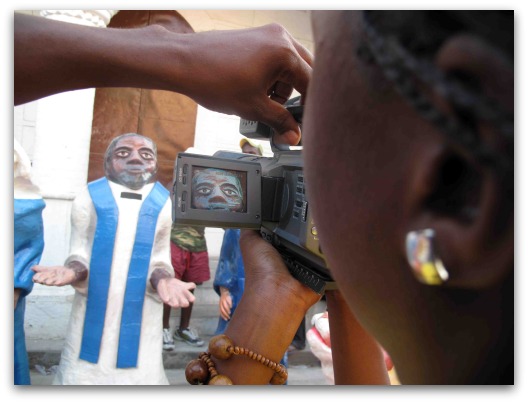

After a few weeks of zipping around Haiti on mototaxis or piled in the back of a black pick-up loaded with my film students and our gear, I began to notice that few female students were pitching me documentary ideas, and most were not shooting. After the earthquake, with the film school’s sudden transformation into a newsroom, our priority shifted away from education. With the furious pace of filming, our urgency to get the stories out, it was only natural to pick the most experienced shooters, who happened to be the boys simply because, well, that’s the way machismo works… they were eager to wield the coveted cameras.

Now as we bounce in the truck bed, a bristling mass of boom poles, cameras, and so many students that every bump threatens to toss a few overboard, I decide we needed to form an all-girl crew.

What kind of stories will the girls want to tell?

Silver, our technical teacher, a proud, laconic Haitian with lingering eyes that seem, perhaps misleadingly, to see everything, loves the idea of being in charge of the girl crew. I’ve known Silver since he was an ambitious boy, weaving and selling hammocks. Haitians have a Creole saying about crabs in a pot, how they are forever climbing on top of each other’s backs to get higher, and get nowhere. It’s not easy to ascend in Haiti, but Silver has done it.

Silver and I take Roudeline, Djuny, Marie Lucie, Roselaure, Enette, all the female students too shy to grab a camera, on all-girl shoots to give them a chance to film, interview and gain the confidence to pitch stories of their own.

Which brings us to the lovely, cheerless Yayi. Roudeline, a gentle girl with a delicate demeanor and insect slim waist, wants to tell stories about elders. She is a steady shooter with a tender eye for details, and shows promise as a filmmaker. She pitched her story and picked her crew but something is wrong with this shoot. Roudeline questions Yayi about her life, her history, her feelings. Yayi’s answers are ever the same: she doesn’t remember ever being happy. She has no happy memories. She gives us nothing but sadness, complaints of diarrhea, shock, confusion, misery. She drags her chair from spot to spot. Why? Perhaps for another vantage point on the yard, crisscrossed with laundry, under which her daughter prepares a fire, chops plantains, guts fish, tosses the guts to the kittens, cooks. Or is the earth still shaking for Yayi, and she can’t find a spot that doesn’t tremble?

Yayi is fading. Drifting. You can see it in the way she drags her chair around the tiny yard, sitting everywhere and nowhere, the way she never smiles, the way she floats off into nowhere. She is leaving the world. She survived Papa Doc and Baby Doc Duvalier, and now an earthquake. Is it time to go?

Tres triste. The story is too sad. Bougon is on camera, Junior on sound. I can see their faces sinking. Junior is an earnest student with an ever-ready smile who I’ve dubbed “Juice Master.” A year ago, when he was a new student working on his first short fiction film, I gave him the job of Prop Master, so that was his name. He was in charge of a chicken, some string, a cane, and a pink plastic basket that was to transform an actress’s flat belly into something more expectant. He was a proud Prop Master. Then a few weeks ago I began calling him Boom Master for his skill at holding the boom. But last week he was put in charge of the generators, and he became Juice Master. These changing names I give him make us laugh every time we see each other. And Bougon…. If Bougon didn’t exist he could never be imagined. Garish sneakers, wild ties, suspenders, vests, there is nobody more stylish than Bougon. His face is an unreadable mix of introspection, explosive joy, childlike wisdom. We glance at each other. How to save this story?

I whisper questions to Roudeline. Ask Yayi about the first time she fell in love. Yayi shakes her head. Her marriage was not good. Ask her about her childhood, what games did she play? Yayi pauses, then says, childhood was not good. She has no good memories of being a child. We ask her about life under the brutal regimes of the Duvaliers. She pauses. “Food was cheaper,” she says. “Now it’s too expensive.”

Yayi rises, drags her chair elsewhere. Maybe it’s us she’s trying to get away from.

I take Roudeline aside. By now we’re giggling a bit, though there is nothing funny here. Yayi is endearing, even in her cloak of woe. She is what she is, like a root, or a barnacle, or a stone. She’s lived long and has no need to talk. But how to capture that? I say, let’s work for contrast. Film the kittens playing, the flutter of laundry. At least her portrait then will have some playful shots.

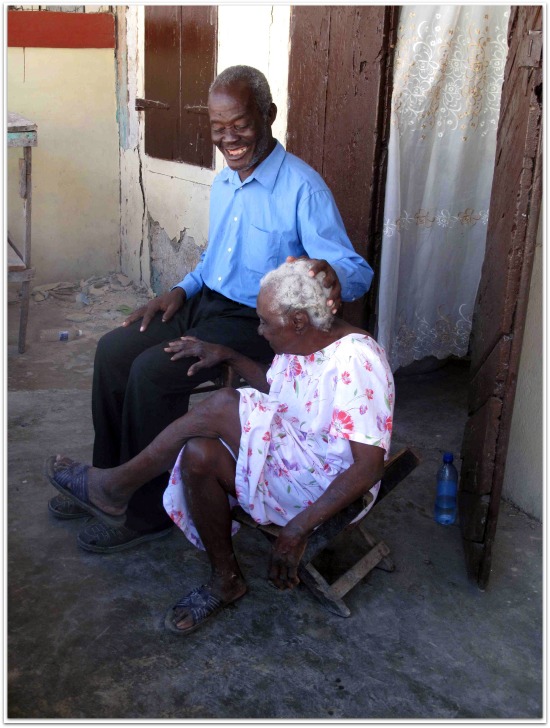

But it isn’t enough. We need another angle on Yayi. We wander out into the street to ask people about her. We question the older men. Turns out a few men in their sixties, 20 years her junior, remember her from when they were little, how she gave them everything she had. One old man says “She gives me stuff. I never give her anything.” Is this the key to her sadness? I wonder. Another says “We are like her children. She gives us medicine even before our family does.” He sits next to her and pats her head. She may have no love left for herself, but there is love for her in his eyes. Is it enough to redeem this sad tale?

Roudeline heads back to the tent we use as a classroom to review her footage. I’ve been screening classic films in the tent. I’ve been teaching Sergei Eisenstein’s montage theory: how you can write sentences with pictures. A shot of a man and then a shot of a flying bird is a different sentence than a shot of a man and then of rain. One is fanciful, one moody. My students are collecting shots; now they have to put them together carefully. I’m excited to see what Roudeline will create.

A few days later Roudeline shows me her Grand Mère film. She’s tried to turn it into an epic, by going out and shooting more old ladies. Old lady after old lady, a procession of old ladies. I try to teach by Aikido: make suggestions, but mostly stay out of their way. Last week I told a student that the camera rising to the sky is a good enough way to show spirituality, he doesn’t need to literally put Jesus’s face in the sky… but he was passionate about his reasons, so there it is, Jesus in the sky. I suggest rather than insist that one old lady is strong enough.

We’re on deadline for Canadian TV. Roudeline decides that her passion for making a film about elders demands a bigger piece, but that for now we’ll shape Grand Mère as a single portrait. The finished film is as perfect as a film made in a few days can be. A film as tender as Roudeline. Off it goes, by bus to Port-au-Prince, then by DHL to Canada.

Once the film is en route, Roudeline vanishes. I ask why she’s not in class. No one knows. A few students mention that her husband is overprotective, old-fashioned. I’m surprised: She seems too young to be married. I’ve done a bit of research for her, found a home for the aged up north a bit, and an organization that might sponsor a film about the elderly, thinking that when Roudeline returns we can work on her bigger film.

Then one day she shows up. I ask her where she’s been. She rubs her belly. Oh, you’ve been sick, I say. The water in Haiti is bad, and students often miss class from bad stomachs. No. She’s pregnant. She tells me she has to drop out of school. I congratulate her on her baby, whisper “bonjour” into her belly, but I’m thinking: Her passion to make a film about elders… what of that?

That night I can’t sleep. I sit outside, next to a mountain of rubble, listening to the dogs howl. I’m staying in a room in a half-collapsed hotel, a room that is probably fine, but an engineer who sleeps in the yard tells me the building isn’t safe. I hedge my bets by sleeping close to the door. The girl in the room above me thinks I’m crazy – if there’s another earthquake, her room will fall on top of me. I tell her I’ll be quick out the door, how will she get out? She shows me the coconut tree out her window, an easy route out of the building.

The nights belong to the dogs. It’s operatic, their crescendo of wails, and I imagine stories to go along with the complex dog dramas. When the moon is a crescent in Haiti, it’s not sideways. It’s a smile in the sky.

One day Roudeline is a promising filmmaker, the next she is a promising mother. What happens in Haiti is what happens. There are places in the world where it pays to push people. But not here.

Come back next Monday for “Whose rubble is it, anyway?”

See Roudeline’s film Grand Mère here.